Transverse myelitis

Transverse myelitis (TM) is a rare neurological condition wherein the spinal cord is inflamed. The adjective transverse implies that the spinal inflammation (myelitis) extends horizontally throughout the cross section of the spinal cord;[1] the terms partial transverse myelitis and partial myelitis are sometimes used to specify inflammation that affects only part of the width of the spinal cord.[1] TM is characterized by weakness and numbness of the limbs, deficits in sensation and motor skills, dysfunctional urethral and anal sphincter activities, and dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system that can lead to episodes of high blood pressure. Signs and symptoms vary according to the affected level of the spinal cord. The underlying cause of TM is unknown. The spinal cord inflammation seen in TM has been associated with various infections, immune system disorders, or damage to nerve fibers, by loss of myelin.[1] As opposed to leukomyelitis which affects only the white matter, it affects the entire cross-section of the spinal cord.[3] Decreased electrical conductivity in the nervous system can result.

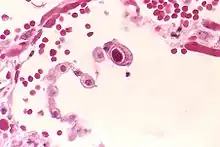

| Transverse myelitis | |

|---|---|

| |

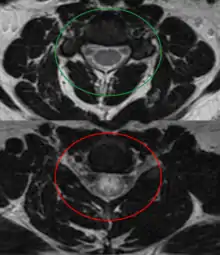

| An MRI showing a transverse myelitis lesion, which is lighter, oval shape at center-right. The patient recovered 3 months later. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Weakness of the limbs[1] |

| Causes | Uncertain[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Neurological exam[2] |

| Treatment | Corticosteroids[2] |

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms include weakness and numbness of the limbs, deficits in sensation and motor skills, dysfunctional urethral and anal sphincter activities, and dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system that can lead to episodes of high blood pressure.[1] Symptoms typically develop for hours to a few weeks.[1][4] Sensory symptoms of TM may include a sensation of pins and needles traveling up from the feet.[1] The degree and type of sensory loss will depend upon the extent of the involvement of the various sensory tracts, but there is often a "sensory level" at the spinal ganglion of the segmental spinal nerve, below which sensation of pain or light touch is impaired. Motor weakness occurs due to the involvement of the pyramidal tracts and mainly affects the muscles that flex the legs and extend the arms.[1]

Disturbances in sensory nerves and motor nerves and dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system at the level of the lesion or below, are noted. Therefore, the signs and symptoms depend on the area of the spine involved.[5] Back pain can occur at the level of any inflamed segment of the spinal cord.[1]

If the upper cervical segment of the spinal cord is involved, all four limbs may be affected and there is the risk of respiratory failure – the phrenic nerve which is formed by the cervical spinal nerves C3, C4, and C5 innervates the main muscle of respiration, the diaphragm.[6]

Lesions of the lower cervical region (C5–T1) will cause a combination of upper and lower motor neuron signs in the upper limbs, and exclusively upper motor neuron signs in the lower limbs. Cervical lesions account for about 20% of cases.[5]

A lesion of the thoracic segment (T1–12) will produce upper motor neuron signs in the lower limbs, presenting as a spastic paraparesis. This is the most common location of the lesion, and therefore most individuals will have weakness in the lower limbs.[7]

A lesion of the lumbar segment, the lower part of the spinal cord (L1–S5) often produces a combination of upper and lower motor neuron signs in the lower limbs. Lumbar lesions account for about 10% of cases.[5]

Causes

TM is a heterogeneous condition, that is, there are several identified causes. Sometimes the term Transverse myelitis spectrum disorder is used.[8] In 60% of patients the cause is idiopathic.[9] In rare cases, it may be associated with meningococcal meningitis[10]

When it appears as a comorbid condition with neuromyelitis optica (NMO), it is considered to be caused by NMO-IgG autoimmunity, and when it appears in multiple sclerosis (MS) cases, it is considered to be produced by the same underlying condition that produces the MS plaques.

Other causes of TM include infections, immune system disorders, and demyelinating diseases.[11] Viral infections known to be associated with TM include HIV, herpes simplex, herpes zoster, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr.[12] Flavivirus infections such as Zika virus and West Nile virus have also been associated. Viral association of transverse myelitis could result from the infection itself or from the response to it.[11] Bacterial causes associated with TM include Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Bartonella henselae, and the types of Borrelia that cause Lyme disease. Lyme disease gives rise to neuroborreliosis which is seen in a small percentage (4 to 5 per cent) of acute transverse myelitis cases.[13] The diarrhea-causing bacteria Campylobacter jejuni is also a reported cause of transverse myelitis.[14]

Other associated causes include the helminth infection schistosomiasis, spinal cord injuries, vascular disorders that impede the blood flow through vessels of the spinal cord, and paraneoplastic syndrome.[11] Another exceptionally rare cause is heroin associated transverse myelitis.[15][16]

Pathophysiology

This progressive loss of the fatty myelin sheath surrounding the nerves in the affected spinal cord occurs for unclear reasons following infections or due to multiple sclerosis. Infections may cause TM through direct tissue damage or by immune-mediated infection-triggered tissue damage.[4] The lesions present are usually inflammatory. Spinal cord involvement is usually central, uniform, and symmetric in comparison to multiple sclerosis which typically affects the cord in a patchy way and the lesions are usually peripheral. The lesions in acute TM are mostly limited to the spinal cord with no involvement of other structures in the central nervous system.[4]

Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis

A proposed special clinical presentation is the "longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis" (LETM), which is defined as a TM with a spinal cord lesion that extends over three or more vertebral segments.[17] The causes of LETM are also heterogeneous[18] and the presence of MOG auto-antibodies has been proposed as a diagnostic biomarker.[19]

Diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria

In 2002, the Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group proposed the following diagnostic criteria for idiopathic acute transverse myelitis:[20]

- Inclusion criteria

- Motor, sensory or autonomic dysfunction attributable to spinal cord

- Signs and symptoms on both sides of the body (not necessarily symmetrical)

- Clearly defined sensory level

- Signs of inflammation (pleocytosis of the cerebrospinal fluid, or elevated immunoglobulin G, or evidence of inflammation on gadolinium-enhanced (MRI) Magnetic resonance imaging)

- Peak of this condition can occur anytime between 4 hours to 21 days after onset

- Exclusion criteria

- Irradiation of the spine (e.g., radiotherapy) in the last 10 years

- Evidence of thrombosis of the anterior spinal artery

- Evidence of extra-axial compression on neuroimaging

- Evidence of arteriovenous malformation (abnormal flow voids on surface of spine)

- Evidence of connective tissue disease, e.g. sarcoidosis, Behçet's disease, Sjögren's syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus or mixed connective tissue disease

- Evidence of optic neuritis (diagnostic of neuromyelitis optica (NMO))

- Evidence of infection (syphilis, Lyme disease, Human immunodeficiency virus, Human T-lymphotropic virus 1, mycoplasma, Herpes simplex virus, Varicella-zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, Human herpesvirus 6 or enteroviruses)

- Evidence of multiple sclerosis (abnormalities detected on MRI and presence of oligoclonal antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF))

Investigations

Individuals who develop TM are typically transferred to a neurologist who can urgently investigate the patient in a hospital. If breathing is affected, particularly in upper spinal cord lesions, methods of artificial ventilation must be on hand before and during the transfer procedure. The patient should also be catheterized to test for and, if necessary, drain an over-distended bladder. A lumbar puncture can be performed after the MRI or at the time of CT myelography. Corticosteroids are often given in high doses when symptoms begin with the hope that the degree of inflammation and swelling of the spinal cord will be lessened, but whether this is truly effective is still debated.[2]

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of acute TM includes demyelinating disorders, such as multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica, infections, such as herpes zoster and herpes simplex virus, and other types of inflammatory disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and neurosarcoidosis. It is important to also rule out an acute cause of compression on the spinal cord.[21]

Treatment

If treated early, some people experience a complete or near complete recovery. Treatment options also vary according to the underlying cause. One treatment option includes plasmapheresis.[22] Recovery from TM is variable between individuals and also depends on the underlying cause. Some patients begin to recover between weeks 2 and 12 following onset and may continue to improve for up to two years. Other patients may never show signs of recovery.[23]

Prognosis

The prognosis for TM depends on whether there is improvement in 3 to 6 months. Complete recovery is unlikely if no improvement occurs within this time. Incomplete recovery can still occur; however, aggressive physical therapy and rehabilitation will be very important. One-third of people with TM experience full recovery, one-third experience fair recovery but have significant neurological deficits, such as spastic gait. The final third experience no recovery at all.[11]

Epidemiology

The incidence of TM is 4.6 per 1 million per year, affecting men and women equally. TM can occur at any age, but there are peaks around age 10, age 20, and after age 40.[24]

History

The earliest reports describing the signs and symptoms of transverse myelitis were published in 1882 and 1910 by the English neurologist Henry Bastian.[5][25]

In 1928, Frank Ford noted that in mumps patients who developed acute myelitis, symptoms only emerged after the mumps infection and associated symptoms began to recede. In an article in The Lancet, Ford suggested that acute myelitis could be a post-infection syndrome in most cases (i.e. a result of the body's immune response attacking and damaging the spinal cord) rather than an infectious disease where a virus or some other infectious agent caused paralysis. His suggestion was consistent with reports in 1922 and 1923 of rare instances in which patients developed "post-vaccinal encephalomyelitis" subsequent to receiving the rabies vaccine which then was made from brain tissue carrying the virus. The pathological examination of those who had died from the disease revealed inflammatory cells and demyelination as opposed to the vascular lesions predicted by Bastian.[26]

Ford's theory of an allergic response being at the root of the disease was later shown to be only partially correct, as some infectious agents such as mycoplasma, measles and rubella[27] were isolated from the spinal fluid of some infected patients, suggesting that direct infection could contribute to the manifestation of acute myelitis in certain cases.

In 1948, Dr. Suchett-Kaye described a patient with rapidly progressing impairment of lower extremity motor function that developed as a complication of pneumonia. In his description, he coined the term transverse myelitis to reflect the band-like thoracic area of altered sensation that patients reported.[5] The term 'acute transverse myelopathy' has since emerged as an acceptable synonym for 'transverse myelitis', and the two terms are currently used interchangeably in the literature.[28]

The definition of transverse myelitis has also evolved over time. Bastian's initial description included few conclusive diagnostic criteria; by the 1980s, basic diagnostic criteria were established, including acutely developing paraparesis combined with bilateral spinal cord dysfunction for <4 weeks and a well-defined upper sensory level, no evidence of spinal cord compression, and a stable, non-progressive course.[29][30] Later definitions, were written to exclude patients with underlying systemic or neurological illnesses and to include only those who progressed to maximum deficit in fewer than 4 weeks.[31]

Society and culture

In 2016, former Slipknot drummer Joey Jordison revealed that he had been hospitalised by the disease in 2013 and that this was the reason for his controversial firing.[32] As the first celebrity to publicly speak about having transverse myelitis, this helped to raise public awareness of the disease. Jordison died in his sleep on July 26, 2021,[33] however it is not known whether the disease had any connection to his death.

Etymology

The word is from Latin: myelitis transversa and the disorder's name is derived from Greek myelós referring to the "spinal cord", and the suffix -itis, which denotes inflammation.[34]

See also

References

- West TW (October 2013). "Transverse myelitis--a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and initial management". Discovery Medicine. 16 (88): 167–177. PMID 24099672.

- "Transverse myelitis". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Servant S (1999). "Entzündliche Rückenmarkerkrankungen". In Knecht S (ed.). Klinische Neurologie. pp. 485–96. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-08118-1_21. ISBN 978-3-662-08119-8.

- Awad A, Stüve O (September 2011). "Idiopathic transverse myelitis and neuromyelitis optica: clinical profiles, pathophysiology and therapeutic choices". Current Neuropharmacology. 9 (3): 417–428. doi:10.2174/157015911796557948. PMC 3151596. PMID 22379456.

- Dale RC, Vincent A (2010). Inflammatory and Autoimmune Disorders of the Nervous System in Children. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 96–106. ISBN 978-1-898683-66-7.

- Misra UK, Kalita J (2011-01-01). Diagnosis & Management of Neurological Disorders. Wolters kluwer india Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-81-8473-191-0.

- Alexander MA, Matthews DJ, Murphy KP (2015). Pediatric Rehabilitation, Fifth Edition: Principles and Practice. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 523, 524. ISBN 978-1-62070-061-7.

- Pandit L (Mar–Apr 2009). "Transverse myelitis spectrum disorders". Neurology India. 57 (2): 126–133. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.51278. PMID 19439840.

- "What is Transverse Myelitis (TM)? | Johns Hopkins Transverse Myelitis Center". Retrieved 2018-07-22.

- Khare KC, Masand U, Vishnar A (February 1990). "Transverse myelitis--a rare complication of meningococcal meningitis". The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 38 (2): 188. PMID 2380146.

- "Transverse Myelitis Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Archived from the original on 2016-11-23. Retrieved 2015-08-06.

- Levin SN, Lyons JL (January 2018). "Infections of the Nervous System". The American Journal of Medicine (Review). 131 (1): 25–32. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.08.020. PMID 28889928.

- Blanc F, Froelich S, Vuillemet F, Carré S, Baldauf E, de Martino S, et al. (November 2007). "[Acute myelitis and Lyme disease]". Revue Neurologique. 163 (11): 1039–1047. doi:10.1016/S0035-3787(07)74176-0. PMID 18033042.

- Ross AG, Olds GR, Cripps AW, Farrar JJ, McManus DP (May 2013). "Enteropathogens and chronic illness in returning travelers". The New England Journal of Medicine (Review). 368 (19): 1817–1825. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1207777. hdl:10072/54169. PMID 23656647. S2CID 13789364.

- Hussain M, Shafer D, Taylor J, Sivanandham R, Vasquez H (2023-07-02). "Heroin-Induced Transverse Myelitis in a Chronic Heroin User: A Case Report". Cureus. 15 (7): e41286. doi:10.7759/cureus.41286. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 10315196. PMID 37405127.

- Sidhu MK, Mekala AP, Ronen JA, Hamdan A, Mungara SS (June 2021). "Heroin Relapse "Strikes a Nerve": A Rare Case of Drug-Induced Acute Myelopathy". Cureus. 13 (6): e15865. doi:10.7759/cureus.15865. PMC 8301723. PMID 34327090.

- Cuello JP, Romero J, de Ory F, de Andrés C (September 2013). "Longitudinally extensive varicella-zoster virus myelitis in a patient with multiple sclerosis". Spine. 38 (20): E1282–E1284. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31829ecb98. PMID 23759816. S2CID 205519782.

- Pekcevik Y, Mitchell CH, Mealy MA, Orman G, Lee IH, Newsome SD, et al. (March 2016). "Differentiating neuromyelitis optica from other causes of longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis on spinal magnetic resonance imaging". Multiple Sclerosis. 22 (3): 302–311. doi:10.1177/1352458515591069. PMC 4797654. PMID 26209588.

- Cobo-Calvo Á, Sepúlveda M, Bernard-Valnet R, Ruiz A, Brassat D, Martínez-Yélamos S, et al. (March 2016). "Antibodies to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in aquaporin 4 antibody seronegative longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis: Clinical and prognostic implications". Multiple Sclerosis. 22 (3): 312–319. doi:10.1177/1352458515591071. PMID 26209592. S2CID 8356201.

- Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group (August 2002). "Proposed diagnostic criteria and nosology of acute transverse myelitis". Neurology. 59 (4): 499–505. doi:10.1212/WNL.59.4.499. PMID 12236201.

- Jacob A, Weinshenker BG (February 2008). "An approach to the diagnosis of acute transverse myelitis". Seminars in Neurology. 28 (1): 105–120. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1019132. PMID 18256991.

- Cohen JA, Rudick RA (2011). Multiple Sclerosis Therapeutics. Cambridge University Press. p. 625. ISBN 978-1-139-50237-5.

- "Transverse Myelitis Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Archived from the original on 2016-11-23. Retrieved 2007-09-16.

About one-third of patients do not recover at all: These patients are often wheelchair-bound or bedridden, with marked dependence on others for basic functions of daily living.

- Mumenthaler M, Mattle H (2011). Neurology. Thieme. ISBN 978-1-60406-135-2.

- Quain R, ed. (1882). A Dictionary of Medicine: Including General Pathology, General Therapeutics, Hygiene, and the Diseases Peculiar to Women and Children. Vol. 2. Longmans, Green, and Company. pp. 1479–83.

- Kerr D. "The History of TM: The Origins of the Name and the Identification of the Disease". The Transverse Myelitis Association. Retrieved 2018-07-22.

- Morris MH, Robbins A (1943-09-01). "Acute infectious myelitis following rubella". The Journal of Pediatrics. 23 (3): 365–67. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(43)80017-2.

- Krishnan C, Kaplin AI, Deshpande DM, Pardo CA, Kerr DA (May 2004). "Transverse Myelitis: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment". Frontiers in Bioscience. 9 (1–3): 1483–1499. doi:10.2741/1351. PMID 14977560.

- Berman M, Feldman S, Alter M, Zilber N, Kahana E (August 1981). "Acute transverse myelitis: incidence and etiologic considerations". Neurology. 31 (8): 966–971. doi:10.1212/WNL.31.8.966. PMID 7196523. S2CID 42676273.

- Ropper AH, Poskanzer DC (July 1978). "The prognosis of acute and subacute transverse myelopathy based on early signs and symptoms". Annals of Neurology. 4 (1): 51–59. doi:10.1002/ana.410040110. PMID 697326. S2CID 38183956.

- Christensen PB, Wermuth L, Hinge HH, Bømers K (May 1990). "Clinical course and long-term prognosis of acute transverse myelopathy". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 81 (5): 431–435. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.1990.tb00990.x. PMID 2375246. S2CID 44660348.

- "Ex-Slipknot Drummer Reveals Struggle With Rare Disease: 'I Lost My Legs'". Billboard.com. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- Atkinson K. "Ex-Slipknot Drummer Joey Jordison Dies at 46". Billboard.com. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- Chamberlin SL, Narins B, eds. (2005). The Gale Encyclopedia of Neurological Disorders. Detroit: Thomson Gale. pp. 1859–70. ISBN 978-0-7876-9150-9.

Further reading

- Frontera WR, Silver JK, Rizzo TD (2008). Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Musculoskeletal Disorders, Pain, and Rehabilitation. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4160-4007-1.

- Cassell DK, Rose NR (2003). The Encyclopedia of Autoimmune Diseases. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-2094-2.