Travellers and Magicians

Travellers and Magicians[lower-alpha 1] is a 2003 Bhutanese Dzongkha-language film written and directed by Khyentse Norbu, writer and director of the arthouse film The Cup. The movie is the first feature film shot entirely in the Kingdom of Bhutan. The majority of the cast are not professional actors; Tshewang Dendup, a well-known Bhutanese radio actor and producer, is the exception.

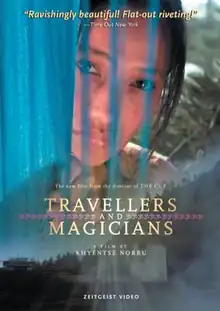

| Travellers and Magicians | |

|---|---|

DVD cover | |

| Directed by | Khyentse Norbu |

| Written by | Khyentse Norbu |

| Produced by | Raymond Steiner Malcolm Watson |

| Starring | Neten Chokling Tshewang Dendup Lhakpa Dorji Sonam Kinga Sonam Lhamo Deki Yangzom |

| Cinematography | Alan Kozlowski |

| Edited by | John Scott Lisa-Anne Morris |

| Distributed by | Zeitgeist Films |

Release date | 2003 |

Running time | 108 minutes |

| Country | Bhutan |

| Language | Dzongkha |

| Budget | $1.8 million[1] |

Plot

A young government official named Dondup (played by Tshewang Dendup) who is smitten with United States (he even has a denim gho) dreams of escaping there while stuck in a beautiful but isolated village. He hopes to connect in the U.S. embassy with a visa out of the country. He misses the one bus out of town to Thimphu, however, and is forced to hitchhike and walk along the Lateral Road to the west, accompanied by an apple seller, a Buddhist monk with his ornate, dragon-headed dramyin heading to Thimphu, a drunk, a widowed rice paper maker and his daughter Sonam (played by Sonam Lhamo).

To pass the time, the monk tells the tale of Tashi, a restless farmboy who, like Dondup, dreams of escaping village life. Tashi rides a horse that goes into a forest. He immediately becomes lost in remote mountains and finds his life entwined with that of an elderly hermit woodcutter and his beautiful young wife. Tashi's wish of escape granted, he finds himself caught in a web of lust and jealousy, enchanted by the beautiful and yielding wife, but fearing the woodsman and his axe. Tashi finally tries to murder the woodcutter, aided by his wife who is pregnant by Tashi. He runs away, however, while the old man is near death, burdened by his guilt. Deki, the woodcutter's wife calls and runs after him, but drowns in a mountain river while giving pursuit.

Tashi's adventures finally turn out to be hallucinations induced by chhaang, a home-brewed liquor. The monk's tale merely parallels Dondup's growing attraction to Sonam. During a dilemma similar to Tashi's, Dondup manages to hitch a ride to Thimphu. The film ends without showing the final outcome of Dondup's journey - his visa interview and his trip abroad. The audience is left to wonder whether the trip changed his attitude toward the village and Bhutan, and if he returned to the village.

Themes

According to the director, the story of Dendup was inspired by Izu No Odoriko (The Dancing Girl of Izu), a story by Yasunari Kawabata about a group of travellers and an infatuation between a dancing girl and a schoolboy. The story of Tashi was inspired by a Buddhist fable about two brothers, one of whom aspires to become a magician.[3][4]

In making this movie, Khyentse Norbu, (also known as Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche, an internationally renowned Buddhist lama), sets the standard for the nascent Bhutanese film industry. The story depicts traditional Bhutanese folklore and storytelling techniques. Travellers and Magicians is a profoundly Bhutanese film, with a theme and vocabulary that reflects the culture of Bhutan.

The storytelling technique employed in the film is the one of a story within a story, as the monk narrates the story of Tashi. The nesting of worlds goes three levels deep, as Tashi hallucinates/dreams after consuming chhang.

Traditional and fusion music is used, with Western rock and Western-influenced music being heard via Dondup's music system and traditional music from the dramyin of the monk and as ambient music. The noted chant music advocate David Hykes contributed music at the invitation of the director. A soundtrack of the movie has been commercially released.[3]

Since only a quarter of the people of Bhutan have the mother tongue of Dzongkha, one of the cast members — Sonam Kinga — acted as a dialect coach to the cast.[3]

Production

In keeping with the production of Norbu's previous movie The Cup, no professional actors (save Dendup: a radio actor) were used. Auditions were held to select the cast from all walks of life including farmers, schoolchildren, and employees of the Bhutan Broadcasting Service, Government of Bhutan, and the Royal Bodyguard. Many production decisions, including casting and fixing the date of release, were chosen using Mo — an ancient method of divination.[3][5]

Release and reception

Box office

According to Box Office Mojo, the film was in release for 28 weeks and its total lifetime grosses were $668,639.[6]

Critical reception

Travellers and Magicians received positive reviews from critics. Variety film critic David Stratton praised the "natural and unaffected" acting by the film's cast.[7] Salon's Andrew O'Hehir gave the film a positive review and wrote that "[Travellers and Magicians] won't rock your cinematic sense of self, I guess, but it's a smart, winsome and often beautiful little picture; I didn't want it to end".[8] Dessen Thompson, writing for The Washington Post, praised the film as "deeply enchanting".[9] In his review of the film for Slant, Josh Vasquez gave the film two and a half stars out four.[10] In his review of the film published in The New York Times, Dave Kehr described it as a "pleasant, colorful travelogue".[11]

The review-aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 93% based on 61 reviews from critics, with an average rating of 7.35/10. The website's "Critics Consensus" for the film reads, "Interwined tales of spiritual discovery are set against a gorgeous, evocative landscape in this pleasant, engaging import."[12] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 71 out of 100, based on 19 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[13]

Accolades

- Audience award, Deauville Asian Film Festival

- Best emerging director, Asian American International Film festival

| Year | Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | SAARC Film Festival | Best Feature Film Silver Medal | Won | [14] | |

Notes

Explanatory notes

References

- Clayton, Sue (April 2007). "Film-making in Bhutan: The view from Shangri-La". New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film. 5 (1): 79. doi:10.1386/ncin.5.1.75_4.

- Halkias, Georgios T. (December 2018). "Great Journeys in Little Spaces: Buddhist Matters in Khyentse Norbu's Travellers and Magicians". International Journal of Buddhist Thought and Culture. 28 (2): 205–223. doi:10.16893/IJBTC.2018.12.28.2.205.

- US Press Kit Archived 2007-01-02 at the Wayback Machine, Travellers and Magicians website

- Pearlman, Bari (1 April 2005). "Once Upon A Time in Bhutan". Filmmaker. Archived from the original on 11 August 2006. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Ryan, Catherine (27 April 2005). "The adventure of making 'Travellers and Magicians'". The Union. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- "Travellers and Magicians (2005)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Stratton, David (8 September 2003). "Travellers And Magicians". Variety. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- O'Hehir, Andrew (3 February 2005). "Beyond the Multiplex". Salon. Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Thompson, Dessen (11 February 2005). "'Travellers': Simply Magical". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Vasquez, Josh (27 January 2005). "Review: Travellers and Magicians". Slant. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Kehr, David (28 January 2005). "Nothing Like a Pretty Girl to Energize the Quiet Life". New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 September 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Travelers and Magicians (2005)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- "Travelers and Magicians Reviews". Metacritic. 28 January 2005. Archived from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- "Winners – SAARC Film Festival 2016". SAARC Culture. 7 June 2016. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

External links

- Travellers and Magicians at IMDb

- Words of My Perfect Teacher, a documentary on Khyentse Norbu