Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919)

The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (French: Traité de Saint-Germain-en-Laye) was signed on 10 September 1919 by the victorious Allies of World War I on the one hand and by the Republic of German-Austria on the other. Like the Treaty of Trianon with Hungary and the Treaty of Versailles with Germany, it contained the Covenant of the League of Nations and as a result was not ratified by the United States but was followed by the US–Austrian Peace Treaty of 1921.

| Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Austria | |

|---|---|

Austrian chancellor Renner addressing the delegates during the signing ceremony | |

| Signed | 10 September 1919 |

| Location | Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Île-de-France, France |

| Effective | 16 July 1920 |

| Condition | Ratification by Austria and four Principal Allied Powers |

| Parties | |

| Depositary | French Government |

| Languages | French, English, Italian |

| Full text | |

| Paris Peace Conference |

|---|

|

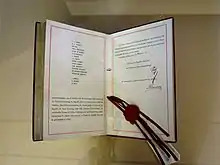

The treaty signing ceremony took place at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye.[1]

Background

As a preamble, on 21 October 1918, 208 German-speaking delegates of the Austrian Imperial Council had convened in a "provisional national assembly of German-Austria" at the Lower Austrian Landtag. When the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Army culminated at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, the Social Democrat Karl Renner was elected German-Austrian State Chancellor on 30 October. In the course of the Aster Revolution on 31 October, the newly established Hungarian People's Republic under Minister President Mihály Károlyi declared the real union with Austria terminated.

With the Armistice of Villa Giusti on 3 November 1918, the fate of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy was sealed. On 11 November 1918 Emperor Charles I of Austria officially declared to "relinquish every participation in the administration", one day later the provisional assembly declared German-Austria a democratic republic and part of the German Republic. However, on the territory of the Cisleithanian ("Austrian") half of the former empire, the newly established states of Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Yugoslav Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the "successor states") had been proclaimed. Moreover, South Tyrol and Trentino were occupied by Italian forces and Yugoslav troops entered the former Duchy of Carinthia, leading to violent fights.

An Austrian Constitutional Assembly election was held on 16 February 1919. The Assembly re-elected Karl Renner state chancellor and enacted the Habsburg Law concerning the banishment of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine. When Chancellor Renner arrived at Saint-Germain in May 1919, he and the Austrian delegation found themselves excluded from the negotiations led by French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau. Upon an Allied ultimatum, Renner signed the treaty on 10 September. The Treaty of Trianon in June 1920 between Hungary and the Allies completed the disposition of the former Dual Monarchy.

Provisions

The treaty declared that the Austro-Hungarian Empire was to be dissolved. According to article 177 Austria, along with the other Central Powers, accepted responsibility for starting the war. The new Republic of Austria, consisting of most of the German-speaking Danubian and Alpine provinces in former Cisleithania, recognized the independence of Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The treaty included 'war reparations' of large sums of money, directed towards the Allies (however the exact amount has never been defined and collected from Austria), as well as provisions for the liquidation of the Austro-Hungarian Bank.

Territory

Cisleithanian Austria had to face significant territorial losses, amounting to over 60 percent of the prewar Austrian Empire's territory:

- The Lands of the Bohemian Crown, i.e. the Bohemia and Moravia crownlands (including small adjacent Lower Austrian territories around Feldsberg and Gmünd) formed the core of the newly created state of Czechoslovakia. The Austrian Silesia province which was the subject of the Polish–Czechoslovak War of January 1919, was split between Czech Silesia and Polish Cieszyn Silesia, and incorporated into the Silesian Voivodeship. These cessions concerned a large German-speaking population in German Bohemia and Sudetenland.

- The former Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, made up of the territory the Habsburg monarchy had annexed in the 1772 First Partition of Poland, fell back to the re-established Polish Republic.

- The adjacent Bukovina in the east passed to the Kingdom of Romania.

- The southern half of the former Tyrolean crownland up to the Brenner Pass, including predominantly Southern Bavarian-speaking South Tyrol and the present-day Trentino province, together with the Carinthian Canal Valley around Tarvisio fell to Italy, as well as the Austrian Littoral (Gorizia and Gradisca, the Imperial Free City of Trieste, and Istria as recognized by the Treaty of Rapallo in 1920).[2]

- The main part of the former Kingdom of Dalmatia, the Duchy of Carniola and Lower Styria with the Carinthian Mieß (Meža) Valley and Gemeinde Seeland (Jezersko) was ceded to the Yugoslav Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, contrary to what was stipulated by the 1915 London Pact. Also Bosnia and Herzegovina was given to it. The affiliation of the Southern Carinthian territory with its Slovene-speaking share of population was to be decided in a Carinthian Plebiscite.

- Austria-Hungary's only overseas possession, its concession in Tianjin, was turned over to China.

- The predominantly German- and Croatian-speaking western parts of the Hungarian counties of Moson, Sopron and Vas were awarded to Austria. The Uprising in West Hungary led to a plebiscite which resulted in the transition of Sopron and its surrounding 8 villages back to Hungary. Subsequently, other villages were returned or exchanged between Austria and Hungary up to 1923. In the end, the territories finally gained from Hungary were organised as a state of Austria named Burgenland.

The Allies had explicitly committed themselves to the cause of the minority peoples of Austria-Hungary late in the war. Indeed, U. S. Secretary of State Robert Lansing had effectively ended what slim chance existed for Austria-Hungary to survive the war when he told Vienna that since the Allies were now committed to the Czechs, Slovaks and South Slavs, autonomy for the nationalities–the tenth of the Fourteen Points–was no longer enough. Reflecting this, the Allies not only allowed the minority peoples to help create new states (Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia), recreate former states (Poland), or join their ethnic brethren in existing nation-states (Romania, Italy), but allowed the successor states to absorb significant blocks of German-inhabited territory. In addition the negotiators on the Allied side, particularly Wilson, did not understand when speaking of self-determination that no convenient line could be drawn to separate intermingled nationalities, and that in further cases, irredentists would claim that some German or Hungarian-inhabited territories had actually been theirs. This was as well rendered by the fact that in just a few cases were plebiscites allowed regarding the disputed territories to ascertain the wishes of the local populaces.

Politics and military

Article 88 of the treaty required Austria to refrain from directly or indirectly compromising its independence, which meant that Austria could not enter into political or economic union with the German Reich without the agreement of the council of the League of Nations. Accordingly, the new republic's initial self-chosen name of German-Austria (German: Deutschösterreich) had to be changed to Austria. Many Austrians would come to find this term harsh (especially among the Austrian Germans being a vast majority who would support a single German nation state), due to Austria's later economic weakness, which was caused by loss of land. Because of all these reasons, Austria would later lead to support for the idea of Anschluss (political union) with Nazi Germany.

Conscription was abolished and the Austrian Army was limited to a force of 30,000 volunteers. There were numerous provisions dealing with Danubian navigation, the transfer of railways, and other details involved in the breakup of a great empire into several small independent states.

The vast reduction of population, territory and resources of the new Austria relative to the old empire wreaked havoc on the economy of the old nation, most notably in Vienna, an imperial capital now without an empire to support it. For a time, the country's very unity was called into question.

See also

Notes

- "Austrian treaty signed in amity". The New York Times. 11 September 1919. p. 12.

- Moos, Carlo (2017), "Südtirol im St. Germain-Kontext", in Georg Grote and Hannes Obermair (ed.), A Land on the Threshold. South Tyrolean Transformations, 1915–2015, Oxford-Berne-New York: Peter Lang, pp. 27–39, ISBN 978-3-0343-2240-9

External links

- Animated map of Europe at the end of the First World War

- Text of the Treaty, from the website of the Australasian Legal Information Institute, hosted by UNSW and UTS

- A full text of the treaty, with signatories