Treveri

The Trēverī (Gaulish: *Trēweroi) were a Germanic and/or Celtic[1] tribe of the Belgae group who inhabited the lower valley of the Moselle in modern day Germany from around 150 BCE, if not earlier,[2] until their displacement by the Franks.[3] Their domain lay within the southern fringes of the Silva Arduenna (Ardennes Forest), a part of the vast Silva Carbonaria, in what are now Luxembourg, southeastern Belgium and western Germany;[4] its centre was the city of Trier (Augusta Treverorum), to which the Treveri give their name.[5] Celtic in language,[6] according to Tacitus they claimed Germanic descent.[7] They contained both Gallic and Germanic influences.[8]

Although early adopters of Roman material culture,[9] the Treveri had a chequered relationship with Roman power. Their leader Indutiomarus led them in revolt against Julius Caesar during the Gallic Wars;[10] much later, they played a key role in the Gaulish revolt during the Year of the Four Emperors.[11] On the other hand, the Treveri supplied the Roman army with some of its most famous cavalry,[10] and the city of Augusta Treverorum was home for a time to the family of Germanicus, including the future emperor Gaius (Caligula).[12] During the Crisis of the Third Century, the territory of the Treveri was overrun by Germanic Alamanni and Franks[13] and later formed part of the Gallic Empire.

Under Constantine and his 4th-century successors, Augusta Treverorum became a large, favoured, rich and influential city that served as one of the capitals of the Roman Empire (together with Nicomedia (present-day İzmit, Turkey), Eboracum (present-day York, England), Mediolanum (present-day Milan, Italy) and Sirmium).[14] During this period, Christianity began to succeed the imperial cult and the worship of Roman and Celtic deities as the favoured religion of the city. Such Christian luminaries as Ambrose, Jerome, Martin of Tours and Athanasius of Alexandria spent time in Augusta Treverorum.[15]

Among the surviving legacies of the ancient Treveri are Moselle wine from Luxembourg and Germany (introduced during Roman times)[16] and the many Roman monuments of Trier and its surroundings, including neighbouring Luxembourg.[17]

Three Roman roads, very important for their role in transregional trade and military deployment capability, went through the territory of the Treveri:

- the first came from the south, connected Divodurum (Metz, France) and Ricciacus (Dalheim, Luxembourg) with Augusta Treverorum (Trier, Germany) and went further to the Rhine river in the northeast, the border of the Roman Empire

- the second came from the southwest and connected Durocortorum (Reims, France) with Andethana (Niederanven, Luxembourg) and Augusta Treverorum

- the third went through the Ardennes in present-day Belgium and Luxembourg and connected Durocortorum to the major city and garrison of Colonia Agrippinensis (Cologne/Köln, Germany) on the Rhine river.[18]

Name

Attestations

They are mentioned as Treveri by Caesar (mid-1st c. BC), Pliny (1st c. AD) and Tacitus (early 2nd c. AD),[19][20][21] Trēoúēroi (Τρηούηροι) by Strabo (early 1st c. AD),[22] Tríbēroi (Τρίβηροι) by Ptolemy (2nd c. AD),[23] Trēouḗrōn (Τρηουήρων) by Cassius Dio (3rd c. AD),[24] Treuerorum (gen.) by Orosius (early 5th c. AD),[25] and as Triberorum in the Notitia Dignitatum (5th c. AD).[26][27] The variant Treberi also appears in Pliny, and few highly deviant variant forms are also attested as Trēoũsgroi (Τρηου̃σγροι) in Strabo or Triḗrōn (Τριήρων) in Cassius Dio.[27]

The first syllable is shown long and stressed (Trēverī) in Latin dictionaries,[28] thus giving the Classical Latin pronunciation [ˈtreːwɛriː].

Etymology

The ethnonym Trēverī is a latinized form of Gaulish *Trēueroi (sing. Trēueros). It is generally viewed as referring to 'crossing a river' or to a 'flowing river'.[27] Linguists Rudolf Thurneysen and Xavier Delamarre have proposed to interpret the name as trē-uer- ('ferrymen'), composed of a suffix trē- (earlier *trei- 'through, across'; cf. Lat. trāns, Skt tiráh) attached to -uer- ('water, river'; cf. Skt vār, ON vari 'water'), This etymology is reinforced by the Old Irish cognate treóir (from *trē-uori-), meaning 'ford, place to cross a river'.[29][30] The Treveri also had a special goddess called Ritona, which either means 'that of the ford' (from the stem ritu- 'ford') or 'that of the course' (from the homonym ritu-, rito- 'course'), and a temple dedicated to Uorioni Deo ('goddess of the watercourse').[31][30]

The city of Trier, attested 1st c. AD as Treueris Augusta and on inscriptions as Augusta Trēvērorum (Treuiris in 1065), is named after the tribe.[32][27]

Geography

Territory

In the time of Julius Caesar their territory extended as far as the Rhine north of the Triboci;[33] across the Rhine from them lived the Ubii. Caesar mentions that the Segni and the Condrusi lived between the Treveri and the Eburones, and that the Condrusii and Eburones were clients of the Treveri.[34] Caesar bridged the Rhine in the territory of the Treveri.[10][35] They were bordered on the northwest by the Belgic Tungri (living where the Germani cisrhenani had lived in the time of Caesar and, according to Tacitus, the same people), on the southwest by the Remi, and on the north, beyond the Ardennes and Eifel, by the Eburones. To the south their neighbours were the Mediomatrici[36]

Later the Vangiones and Nemetes, whom ancient sources identify as Germanic, would settle to the east of the Treveri along the Rhine;[37] thereafter, Treveran territory in present-day Germany was probably similar to that which afterwards became the Diocese of Trier.[38] In addition to this area which is formed mainly by the northern part of the Moselle river valley and the neighbouring Eifel region, the Treveri populated also the area of the present-day Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and the major part of the adjacent Belgian Province of Luxembourg.[39] The Rhine valley was removed from Treveran authority with the formation of the province of Germania Superior in the 80s CE.[40] The valley of the Ahr would have marked their northern boundary.

Settlements

Colonia Augusta Treverorum (now Trier, Germany), established under Augustus ca. 17 BCE to guard a crossing of the Moselle, was the capital of their civitas under the Empire.[5][41] There is strong evidence that the recently excavated oppidum on the Titelberg plateau in the extreme southwest of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg was the Treveran capital during the 1st century BCE.[42] An important secondary centre was Orolaunum (now Arlon, capital of the Belgian Province of Luxembourg), which, in Edith Wightman's assessment, "became a kind of regional capital for the western Treveri", attaining "a degree of prosperity only otherwise reached by civitas capitals".[43] The site of La Tranchée des Portes near Étalle, the largest of Belgium by its size (100 hectares) has not still revealed its rank. A recent study shows that it had already human presence around 4000 BCE. Other important pre-Roman centres were located at Martberg, Donnersberg, Wallendorf, Kastel-Staadt, and Otzenhausen.[41]

The transfer of their activities to Trier followed the construction of Agrippa's road linking Trier with Reims which bypassed the Titelberg. During the Roman period, Trier became a Roman colony (in 16 BCE), and the provincial capital of Belgica itself. It was the frequent residence of a number of emperors. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Treveri were divided into five cantons centred respectively on the pre-Roman oppida of the Titelberg, Wallendorf, Kastel, Otzenhausen and the Martberg.[44] Inscriptions from the Roman imperial period indicate that the civitas was divided into at least four pagi: the pagus Vilcias, the pagus Teucorias, the pagus Carucum extending north of Bitburg, and the pagus Ac[...] or Ag[...] (the inscription is incomplete). Wightman tentatively suggests that the pagus Vilcias might have been the western region around Arlon and Longuyon, and the pagus Teucorias the southern region around Tholey.[45] Wightman considers it uncertain whether the Aresaces and Cairacates may originally have been pagi of the Treveri, but asserts that their territory – lying around Mogontiacum (Mainz) – "always showed particularly close cultural connections with Treveran territory".[46] External to the Treveri, but subject to them as clients, were the Eburones and perhaps also the Caeroesi and Paemani.[47]

The 4th-century poet Ausonius lived in Trier under the Gratian's patronage; he is most famous for his poem Mosella, evoking life and scenery along the Treveri's arterial river.[15]

Language and ethnicity

Caesar is not explicit in De Bello Gallico about whether the Treveri are to be considered to belong to Gallia Celtica or Gallia Belgica, although the former hypothesis enjoys some favour.[38] Writing about a century after Caesar, Pomponius Mela identifies the Treveri as the "most renowned" of the Belgae[48] (not to be confounded with the modern-day Belgians).

According to the Roman consul Aulus Hirtius in the 1st century BCE, the Treveri differed little from Germanic peoples in their manner of life and "savage" behaviour.[49] The Treveri boasted of their Germanic origin, according to Tacitus, in order to distance themselves from "Gallic laziness" (inertia Gallorum). But Tacitus does not include them with the Vangiones, Triboci or Nemetes as "tribes unquestionably German".[7] The presence of hall villas of the same type as found in indisputably Germanic territory in northern Germany, alongside Celtic types of villas, corroborates the idea that they had both Celtic and Germanic affinities.[50]

Strabo says that their Nervian and Tribocan neighbours were Germanic peoples who by that point had settled on the left bank of the Rhine, while the Treveri are implied to be Gaulish.[35]

Jerome states that as of the 4th century their language was similar to that of the Celts of Asia Minor (the Galatians).[51] Jerome probably had first-hand knowledge of these Celtic languages, as he had visited both Augusta Treverorum and Galatia.[52]

Very few personal names among the Treveri are of Germanic origin; instead, they are generally Celtic or Latin. Certain distinctively Treveran names are apparently none of the three and may represent a pre-Celtic stratum, according to Wightman (she gives Ibliomarus, Cletussto and Argaippo as examples).[53]

After the Roman conquest, Latin was used extensively by the Treveri for public and official purposes.[54]

Politics and military

Originally the oppida of the Titelberg, Wallendorf, Kastel, Otzenhausen and the Martberg were roughly equal in significance; however, sometime between 100 and 80 BCE, the Titelberg experienced an upsurge of growth which made it "the central oppidum of the Treveri".[55] A large open space in the central square of the Titelberg which would have been used for public meetings of a religious or political nature during the 1st century BCE. By the time of Caesar's invasion, the Treveri seemed to have adopted an oligarchic system of government.[56]

The Treveri had a strong cavalry and infantry, and during the Gallic Wars would provide Julius Caesar with his best cavalry.[57] Under their leader Cingetorix, the Treveri served as Roman auxiliaries. However, their loyalties began to change in 54 BCE under the influence of Cingetorix' rival Indutiomarus.[58] According to Caesar, Indutiomarus instigated the revolt of the Eburones under Ambiorix that year and led the Treveri in joining the revolt and enticing Germanic tribes to attack the Romans.[59] The Romans under Titus Labienus killed Indutiomarus and then put down the Treveran revolt; afterwards, Indutiomarus' relatives crossed the Rhine to settle among the Germanic tribes.[60] The Treveri remained neutral during the revolt of Vercingetorix, and were attacked again by Labienus after it.[61] On the whole, the Treveri were more successful than most Gallic tribes in cooperating with the Romans. They probably emerged from the Gallic Wars with the status of a free civitas exempt from tribute.[62]

In 30–29 BCE, a revolt of the Treveri was suppressed by Marcus Nonius Gallus, and the Titelberg was occupied by a garrison of the Roman army.[63][41] Agrippa and Augustus undertook the organization of Roman administration in Gaul, laying out an extensive series of roads beginning with Agrippa's governorship of Gaul in 39 BCE, and imposing a census in 27 BCE for purposes of taxation. The Romans built a new road from Trier to Reims via Mamer, to the north, and Arlon, thus by-passing by 25 kilometres the Titelberg and the older Celtic route, and the capital was displaced to Augusta Treverorum (Trier) with no signs of conflict.[63] The vicinity of Trier had been inhabited by isolated farms and hamlets before the Romans, but there had been no urban settlement here.[15]

Following the reorganisation of the Roman provinces in Germany in 16 BCE, Augustus decided that the Treveri should become part of the province of Belgica. At an unknown date, the capital of Belgica was moved from Durocortorum Remorum (Reims) to Augusta Treverorum. A significant layer of the Treveran élite seems to have been granted Roman citizenship under Caesar and/or Augustus, by whom they were given the nomen Julius.[56]

During the reigns of Augustus, Tiberius and Claudius, and particularly when Drusus and Germanicus were active in Gaul, Augusta Treverorum rose to considerable importance as a base and supply centre for campaigns in Germany. The city was endowed with an amphitheatre, baths, and other amenities,[64] and for a while Germanicus' family lived in the city.[12] Pliny the Elder reports that Germanicus' son, the future emperor Gaius (Caligula), was born "among the Treveri, at the village of Ambiatinus, above Confluentes (Koblenz)", but Suetonius notes that this birthplace was disputed by other sources.[65]

A faction of Treveri, led by Julius Florus and allied with the Aeduan Julius Sacrovir, led a rebellion of Gaulish debtors against the Romans in 21 CE. Florus was defeated by his rival Julius Indus, while Sacrovir led the Aedui in revolt.[66] The Romans quickly re-established cordial relations with the Treveri under Indus, who promised obedience to Rome; in contrast, they completely annihilated the Aedui who had sided with Sacrovir. Perhaps under Claudius, the Treveri obtained the status of colonia and probably the Latin Right without actually being colonized by Roman veterans.[67] Under Roman rule, there was a senate of the Treveri including about a hundred decurions, of which the executive was formed by two duoviri.[40]

More serious was the revolt that began with Civilis' Batavian insurrection during the Year of the Four Emperors. In 70, the Treveri under Julius Classicus and Julius Tutor and the Lingones under Julius Sabinus joined the Batavian rebellion and declared Sabinus as Caesar.[68] The revolt was quashed, and more than a hundred rebel Treveran noblemen fled across the Rhine to join their Germanic allies; in the assessment of historian Jeannot Metzler, this event marks the end of aristocratic Treveran cavalry service in the Roman army, the rise of the local bourgeoisie, and the beginnings of "a second thrust of Romanization".[69] Camille Jullian attributes to this rebellion the promotion of Durocortorum Remorum (Reims), capital of the perennially loyal Remi, at the expense of the Treveri.[64] By the 2nd and 3rd centuries, representatives of the old élite bearing the nomen Julius had practically disappeared, and a new élite arose to take their place; these would have originated mainly from the indigenous middle class, according to Wightman.[70]

The Treveri suffered from their proximity to the Rhine frontier during the Crisis of the Third Century. Frankish and Alamannic invasions during the 250s led to significant destruction, particularly in rural areas; given the failure of the Roman military to defend effectively against Germanic invasion, country dwellers improvised their own fortifications, often using the stones from tombs and mausoleums.[13]

Meanwhile, Augusta Treverorum was becoming an urban centre of the first importance, overtaking even Lugdunum (Lyon). During the Crisis of the Third Century, the city served as the capital of the Gallic Empire under the emperors Tetricus I and II from 271 to 274. The Treveri suffered further devastation from the Alamanni in 275, following which, according to Jeannot Metzler, "The great majority of agricultural domains lay waste and would never be rebuilt".[71] It is unclear whether Augusta Treverorum itself fell victim to the Alamannic invasion.[15]

From 285 to 395, Augusta Treverorum was one of the residences of the western Roman Emperor, including Maximian, Constantine the Great, Constantius II, Valentinian I, Magnus Maximus, and Theodosius I;[72] from 318 to 407, it served as the seat of the praetorian prefecture of Gaul. By the mid-4th century, the city was counted in a Roman manuscript as one of the four capitals of the world, alongside Rome, Alexandria, and Constantinople.[15] New defensive structures, including fortresses at Neumagen, Bitburg and Arlon, were constructed to defend against Germanic invasion. After a Vandal invasion in 406, however, the imperial residence was moved to Mediolanum (Milan) while the praetorian guard was withdrawn to Arelate (Arles).[73]

Religion

The Treveri were originally polytheists, and following the Roman conquest many of their gods were identified with Roman equivalents or coupled with Roman gods. Among the most important gods worshipped in Treveran territory were Mercury and Rosmerta, Lenus Mars and Ancamna, Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Apollo, Intarabus, and Minerva.[75][76] Among the deities unique to the Treveri were Intarabus, Ritona, Inciona and Veraudunus, and the Xulsigiae.[75] J.-J. Hatt considers that the Treveri, along with their neighbours the Mediomatrici, Leuci, and Triboci, "appeared as pilots in the conservation of native Celtic and pre-Celtic [religious] traditions".[77]

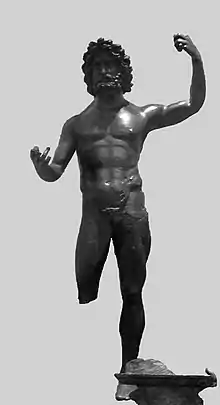

During the Roman period, Lenus Mars (or Mars Iovantucarus) has been deemed "the main god of the Treveri", as evidenced by dedications found across the different sections of civitas Treverorum. They are connected in particular with a monumental sanctuary situated just outside the civitas capital of Trier.[78] The cult of Lenus Mars was probably registered as a public cult in the official calendar of the civitas Treverorum.[79] Three important pagan sanctuaries in the immediate vicinity of Trier alone are well-known: the extensive Altbachtal temple complex, the nearby temple Am Herrenbrünnchen, and the important Lenus Mars Temple on the left bank of the Moselle. Inscriptions attest to the existence of a Treveran cult to Rome and Augustus, but the location of the temple is uncertain. Wightman suggests that the wholly classical and well-endowed temple Am Herrenbrünnchen would be a possibility,[80] while Metzger argues that it can only have been a poorly known fourth temple in the city – the so-called Asclepius Temple not far from the bridge over the Moselle.[81]

The Altbachtal complex has yielded a wealth of inscriptions and the remains of a theatre and over a dozen temples or shrines, mostly Romano-Celtic fana dedicated to native, Roman, and Oriental deities. Outside of the city, many sacred sites are known; they are typically enclosed by a wall. Among these may be mentioned the temple of Apollo and Sirona at Hochscheid, that of Lenus Mars on the Martberg by Pommern, the temple and theatre of Mars Smertrius and Ancamna at Möhn, and a mother-goddess sanctuary at Dhronecken.[82] Under Roman influence, a variety of new cults were introduced: Mithras had a temple in the Altbachtal,[83] Cybele and Attis were worshipped there and at Dhronecken,[84] and inscriptions and artwork attest to other Oriental deities such as Sabazius,[85] Isis and Serapis.[86] Besides the temple of Rome and Augustus mentioned above, the imperial cult is also evidenced by numerous religious inscriptions "in honour of the divine house" (i.e. the imperial family).[87]

In the 4th century, Christianity rose to prominence in Augusta Treverorum. The city became the seat of a Christian archbishopric during the second half of the 3rd century,[88] and under Constantine I, it became an important centre for the diffusion of Christianity. The present-day cathedral has its origins in a 4th-century double church built close to the imperial palace, probably around 321 and perhaps thanks to a donation from Helena Augusta. Approximately four times larger than today's cathedral, this church was one of Constantine's great imperial foundations, ranking with other major churches at Rome, Constantinople, Jerusalem, and Bethlehem.[14][89] Jerome, Athanasius of Alexandria and Martin of Tours all lived and worked in Trier during the 4th century, while Ambrose was born there.[15] In the time of Gratian, the Altbachtal complex was "not so much given up as deliberately destroyed"; cult statues were smashed, and some temples were secularized and made into homes.[90] In 384, the Christian heresiarch Priscillian was executed in Augusta Treverorum on the orders of Magnus Maximus, the Emperor in Britain and Gaul, nominally on charges of sorcery. The Gallic Chronicle of 452 describes the Priscillianists as "Manichaeans", a different Gnostic heresy already outlawed under Diocletian, and states that the emperor had them "caught and exterminated with the greatest zeal" from among the Treveri.[91]

Material culture

The territory of the Treveri had formed part of the Hunsrück-Eifel culture, covering the Hallstatt D and La Tène A-B periods (from 600 to 250 BCE).[92]

During the century from 250 to 150 BCE, the area between the Rhine and the Meuse underwent a drastic population restructuring as some crisis forced most signs of inhabitation onto the heights of the Hunsrück. Following this crisis, population returned to the lowlands and it is possible to speak with confidence of the Treveri by name. Much of the Treveran countryside seems to have been organized into rural settlements by the end of the 2nd century BCE, and this organization persisted into Roman times.[2]

Even before Roman times, the Treveri had developed trade, agriculture and metal-working. They had adopted a money-based economy based upon silver coins, aligned with the Roman denarius, along with cheaper bronze or bronze-lead coins. Trade goods made their way to the Treveri from Etruria and the Greek world; monetary evidence suggests strong trade links with the neighbouring Remi. Iron ore deposits in Treveran territory were heavily worked and formed part of the basis for the area's wealth.[93]

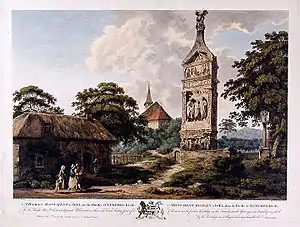

Before and for some time after the Roman conquest, Treveran nobles were buried in chamber tombs which were covered with tumuli and filled with sumptuous goods including imported amphorae, weaponry and andirons.[56] By the 2nd century CE, wealthy Treveri were building elaborate funerary monuments such as the World Heritage-listed Igel Column, or the sculpted grave-stones found at Arlon, Neumagen and Buzenol, all of which depict the deceased's livelihood and/or interests during life. As cremation had become more common under Roman rule, gravestones often had special niches to receive urns of ashes as well as grave-goods. Roman-era grave-goods included the remains of animals used as food (particularly pigs and birds), coins, amphorae, pottery, glassware, jewellery and scissors. Burial replaced cremation again in the late 3rd century.[94]

The Treveri adapted readily to Roman civilization, adopting certain Mediterranean practices in cuisine, clothing, and decorative arts starting as early as the Roman occupation of the Titelberg in 30 BCE.[95] As early as 21 CE, according to Greg Woolf, "the Treveri and the Aedui [were] arguably those tribes which had undergone the greatest cultural change since the conquest".[9] The Romans introduced viticulture to the Moselle valley (see Moselle wine). In general, the archaeological record attests to ongoing rural development and prosperity into the 3rd century CE.[40] Along with the neighbouring Remi, the Treveri can be credited with a significant innovation in Roman technology: the vallus, a machine drawn by horses or mules to reap wheat. The vallus is known from funerary reliefs and literary descriptions.[96] The many individual Treveri attested epigraphically in other civitates may attest to the development of a Treveran commercial network within the western parts of the Empire.[97] During the early 2nd century CE, Augusta Treverorum was an important centre for the production of samian ware (along with Lezoux and Rheinzabern), supplying the Rhineland with high-quality glossy red pottery which was often elaborately decorated with moulded designs.[98]

Treveran villa architecture shows both coexistence and mixture of typically Gallic and Germanic traits. In some villas, such as at Otrang and Echternach, small rooms opened onto a large central hall, rather than onto the front verandah as in most places in Gaul; this arrangement has been considered typically ‘Germanic’, and may reflect a social structure in which extended families and clients all lived in a patron's home. On the other hand, typically ‘Gaulish’ villas are also found in Treveran territory.[50]

List of Treveri

|

|

Notes

- Drinkwater, John Frederick (2012). "Treveri". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191735257. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

Treveri, a Celtic people in the Moselle basin

- Metzler (2003), p. 35.

- Wightman (1970), pp. 250–253.

- Wightman (1970), pp. 21–23.

- Wightman (1970), p. 37.

- Wightman (1970), p. 19.

- Tacitus writes, "The Treveri and Nervii are even eager in their claims of a German origin, thinking that the glory of this descent distinguishes them from the uniform level of Gallic effeminacy." Germania XXVIII.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. p. 802. ISBN 1438129181.

- Woolf (1998), p. 21.

- Caesar, de Bello Gallico.

- Tacitus, Histories.

- Tacitus, Annales I:40–41.

- Metzler (2003), p. 62.

- Wightman (1970), p. 110.

- Eberhard Zahn (n.d.). Trèves : Histoire et Curiosités. Cusanus-Verlag Trier. (in French)

- Wightman (1970), p. 189.

- Jullian (1892), p. 296, remarks, "Seeing all these ruins, still superb today, one senses the supreme effort of the Roman world at the gates of barbarism" (A voir aujourd’hui toutes ces ruines encore superbes, on sent le suprême effort du monde romain à la porte de la barbarie).

- Thill (1973), pp. 77–78.

- Caesar. Commentarii de Bello Gallico, 1:37

- Pliny. Naturalis Historia, 4:6

- Tacitus. Historiae, 1:53

- Strabo. Geōgraphiká, 4:3:4

- Ptolemy. Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis, 2:9:7

- Cassius Dio. Rhōmaïkḕ Historía, XXXIX:47

- Orosius. Historiae Adversus Paganos

- Notitia Dignitatum. oc 9, 37 and 38; 11, 35, 44, 77

- Falileyev 2010, s.v. Treveri and Col. Augusta Treverorum.

- Collins Latin Dictionary Plus Grammar (1997). HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-472092-X.

Perseus Word Study Tool. Morphological Analyses for Inflected Latin Words, - Delamarre (2003), p. 301.

- Zimmer (2006), p. 174.

- Delamarre (2003), pp. 259–260, 301.

- Gysseling (1960), p. 977.

- Caesar, B.G. III:11, IV:3, IV:10.

- Caesar, B.G. IV:6, VI:32.

- Strabo. IV:3, paragraph 3.

- Talbert 2000, Map 11: Sequana-Rhenus.

- Pliny IV.5

- George Long. "Treveri". In William Smith (ed., 1854) Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography.

- Thill (1973), pp. 54–55.

- Metzler (2003), p. 61.

- Binsfeld (2012).

- Elizabeth Hamilton. The Celts and Urbanization – the Enduring Puzzle of the Oppida Archived 2008-04-10 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 21 November 2007.

- Wightman (1970), p. 135.

- Metzler (2003), pp. 36–37.

- Wightman (1970), pp. 124–125.

- Wightman (1970), p. 127.

- Metzler (2003), p. 43, summarizing Caesar, B.G. IV:6, II:4.

- Pomponius Mela (c. 43 AD). De Situ Orbis, III:2. Archived 2008-02-08 at the Wayback Machine The term quoted is "clarissimi". Of course, by this stage, the administrative boundaries of Gallia Belgica had been fixed and did include the Treveri.

- Aulus Hirtius. "Book VIII." In Caesar, B.G. VIII:25.

- King (1990), pp. 153–155.

- Jerome writes, Galatas excepto sermone Graeco, quo omnis oriens loquitur, propriam linguam eamdem pene habere quam Treviros ("That the Galatians, apart from the Greek language, which they speak just like the rest of the Orient, have their own language, which is almost the same as the Treverans'"), in Migne, Patrologia Latina 26, 382.

- Helmut Birkhan (1997). Kelten: Versuch einer Gesamtdarstellung ihrer Kultur. Verlag der Österreich. ISBN 3-7001-2609-3. p. 301. (in German)

- Wightman (1970), pp. 20, 51.

- In the Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss/Slaby, some eleven hundred Latin inscriptions are recorded for the city of Augusta Treverorum alone.

- Metzler (2003), "oppidum central des Trévires", p. 38.

- Metzler (2003), p. 41.

- Caesar, B.G. II:24, V:3.

- Caesar, B.G. V:2.

- Caesar, B.G. V:47, 55.

- Caesar, B.G. VI:8.

- Caesar, B.G. VI:63, VIII:45.

- Metzler (2003), p. 44.

- Metzler (2003), p. 45.

- Jullian (1892), p. 293.

- C. Suetonius Tranquillus (121). De Vita Caesarum. IV:8.

- Tacitus, Annales III:40–42.

- Metzler (2003), p. 58.

- Jona Lendering (2002). "Julius Sabinus". Livius.org: Articles on ancient history. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- Metzler (2003), "une deuxième poussée de romanisation", p. 60.

- Wightman (1970), p. 51.

- Metzler (2003), "La grande majorité des domaines agricoles restent en friche et ne seront plus jamais reconstruits", p. 62.

- Heinen (1985), pp. 211–265.

- Metzler (2003), p. 65.

- The original was purchased for the Musée du Louvre from the collection of Ernest Dupaix, who had excavated the Roman vicus at Dalheim. (Luxembourg Musée National d'Histoire et d'Art: Origines de la collection).

- Nicole Jufer & Thierry Luginbühl (2001). Les dieux gaulois : répertoire des noms de divinités celtiques connus par l'épigraphie, les textes antiques et la toponymie. Paris: Editions Errance. ISBN 2-87772-200-7. (in French)

- William van Andringa (2002). La Religion en Gaule romaine : Piété et politique, Ier-IIIe siècle apr. J.-C. Éditions Errance, ISBN 2-87772-228-7. (in French)

- Jean-Jacques Hatt, Mythes et dieux de la Gaule, tome 2 (unfinished manuscript, posthumously published online Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 29 November 2006), "font figure de pilotes pour la conservation des traditions indigènes celtiques et pré-celtiques", p. 11.

- Derks (1998), p. 96: "For these reasons, Lenus Mars is rightly considered the main god of the Treveri."

- Derks (1998), p. 98.

- Wightman (1970), p. 209.

- Metzler (2003), p. 51.

- Wightman (1970), pp. 215–218, 220, 223–224.

- Kuhnen et al. (1996), pp. 211–214.

- Kuhnen et al. (1996), pp. 217–221.

- AE 1921:50.

- Kuhnen et al. (1996), pp. 222–225.

- Latin: in honorem domus divinae, attested in dozens of inscriptions from the Treveran territory. AE 1929:174 is one example.

- Heinen (1985), pp. 327–347.

- King (1990), pp. 190–193.

- Wightman (1970), p. 229.

- Ames, Christine Cadwell (15 April 2015). Medieval Heresies: Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 45-46. ISBN 9781107023369.

- Metzler (2003), pp. 34–36.

- Metzler (2003), p. 42.

- Wightman (1970), pp. 148–150, 244–248.

- Metzler (2003), p. 46.

- King (1990), pp. 100–101.

- Woolf (1998), p. 134.

- King (1990), pp. 129–130.

References

Primary sources

- Julius Caesar (c. 51 BCE), Commentarii de Bello Gallico (available on Wikisource).

- Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus (c. 387), Comentarii in Epistolam ad Galatos.

- C. Plinius Secundus (c. 77–79), Naturalis historia.

- Strabo (7 BCE–23 CE), Geographica.

- Cornelius Tacitus (117 CE), Annales (available on Wikisource).

- _____ (c. 98 CE), Germania (available on Wikisource).

- _____ (c. 105 CE), Historiae (available on Wikisource).

Secondary sources

- Binsfeld, Andrea (2012). "Augusta Treverorum (Trier)". In Bagnall, Roger S. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah16019. ISBN 978-1-4443-3838-6.</ref>

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental (in French). Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.

- Derks, Ton (1998). Gods, Temples, and Ritual Practices: The Transformation of Religious Ideas and Values in Roman Gaul. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-254-3.

- Falileyev, Alexander (2010). Dictionary of Continental Celtic Place-names: A Celtic Companion to the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. CMCS. ISBN 978-0955718236.

- Gysseling, Maurits (1960). Toponymisch woordenboek van België, Nederland, Luxemburg, Noord-Frankrijk en West-Duitsland voor 1226 (in Dutch). Belgisch Interuniversitair Centrum voor Neerlandistiek.

- Heinen, Heinz (1985). Trier und das Trevererland in römischer Zeit (in German). Universität Trier. ISBN 3-87760-065-4.

- King, Anthony (1990). Roman Gaul and Germany. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06989-7.

- Kuhnen, Hans-Peter; et al. (1996). Religio Romana: Wege zu den Göttern im antiken Trier (in German). Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier. ISBN 3-923319-34-7.

- Metzler, Jeannot (2003). "Le Luxembourg avant le Luxembourg". In Gilbert Trausch (ed.). Histoire du Luxembourg : Le destin européen d'un " petit pays " (in French). Toulouse: Éditions Privat. ISBN 2-7089-4773-7.

- Talbert, Richard J. A. (2000). Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691031699.

- Thill, Gérard (1973). Vor- und Frühgeschichte Luxemburgs. Luxembourg: Bourg-Bourger.

- Wightman, Edith M. (1970). Roman Trier and the Treveri. London: Rupert Hart-Davis. ISBN 0-246-63980-6.

- Woolf, Greg (1998). Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78982-6.

- Zimmer, Stefan (2006). "Treverer". In Beck, Heinrich (ed.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 31 (2 ed.). De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110183863.

Further reading

- Aber, James S. (2004). Volcanism of the Eifel, Germany Region. Emporia, Kansas, USA: Emporia State University. Archived 2016-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Jullian, Camille (1892). Gallia : Tableau sommaire de la Gaule sous la domination romaine (in French). Paris: Librairie Hachette.