Tristichopterus

Tristichopterus, with a maximum length of sixty centimetres, is the smallest genus in the family of prehistoric lobe-finned fish,[1] Tristichopteridae that was believed to have originated in the north and dispersed throughout the course of the Upper Devonian into Gondwana.[2] Tristichopterus currently has only one named species, first described by Egerton in 1861.[3] The Tristichopterus node is thought to have originated during the Givetian part of the Devonian.[4] Tristichopterus was thought by Egerton to be unique for its time period as a fish with ossified vertebral centers, breaking the persistent notochord rule of most Devonian fish[5] but this was later reinspected and shown to be only partial ossification by Dr. R. H. Traquair[6]. Tristichopterus alatus closely resembles Eusthenopteron and this sparked some debate after its discovery as to whether it was a separate taxon.[3]

| Tristichopterus Temporal range: Devonian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Sarcopterygii |

| Clade: | Tetrapodomorpha |

| Clade: | Eotetrapodiformes |

| Family: | †Tristichopteridae |

| Genus: | †Tristichopterus Egerton, 1861 |

| Species: | †T. alatus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Tristichopterus alatus Egerton, 1861 | |

.jpg.webp)

Geology

It is believed that Tristichopterus originated in the Laurasian continent along with the similar Eusthenopteron, and that later derived members, like Eusthenodon, of the Tristichopteridae family achieved wider distribution into Gondwana[2]. The modern day geographical locations that Tristichopterus is thought to have lived in are Australia, Western Europe, and Greenland[7].

Historical Information and Discovery

The two first specimens of Tristichopterus were dug up in the Old Redstone of the John o’ Groats group in Caithness by Charles William Peach and described by Sir Philip Egerton in 1861. A lot of confusion has surrounded this taxon as the first specimens lacked head, fin, and dentition osteology. The original classification by Egerton was to put it in the same family as Dipterus with Coelacanthi.[3]

In 1864 and 1865 Peach obtained further specimens of the genus with clear paired fin, head, and dentition osteology that prevented its placement within the Coelacanthi clade with Dipterus. Ramsay Traquair in 1875 instead included Tristichopterus in the Cyclopteridae family.[3] Later Tristichopterus was assigned its own family.

Eusthenopteron foordi and Tristichopterus alatus are fairly similar in a number of regards but have a couple features between them that prevented the dissolution of either genus upon E. foordi’s discovery by Whiteaves in 1883.[6] Eusthenopteron can be distinguished from Tristichopterus by the possession of two fang pairs on the ectopterygoid and posterior coronoid, a very long posterior coronoid (twice as long as anterior and middle), and ethmosphenoid longer than the oticooccipital and a more symmetric caudal fin. Eusthenopteron is also distinctly larger than Tristichopterus.[1] The original defining features that were used to initially separate the two were the greater symmetricity of E. foordi’s caudal fin and the presence of two cutting edges in the laniary teeth of E. foordi.[6]

Description

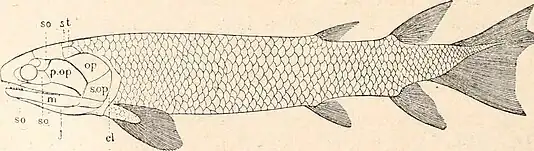

The general form of Tristichopterus is slender with fins biasing towards the posterior parts of its body. The caudal fin is partially between the heterocercal condition of Dipterus and the diphycercal shape of Sirenidae. The rays that compose the fins of Tristichopterus are fine and innumerable and overlapping as in Dipnoi.[3]

The typical specimen is 10.5 inches in length, its head taking up a fifth of that measurement. The greater depth of its body being just behind its subacutely lobate pectorals, measuring at two inches. The first dorsal originates six inches back and the second and 1 and ¼ inches further back. The sets of ventral and anal tails are placed opposite each other. The start of the lower lobe of the caudal fin occurs 8 ¼ inches from the front, its upper lobe beginning a little further back. The pectorals are attached 2 ¼ inches from the front. Most common length of an adult Tristichopterus was thought to be fifteen inches.[3]

The head of Tristichopterus sports a cranial buckler for protection, similar to Saurodipterini, and is divided into an anterior, longer, and a posterior, wider, parts. External nares on the original specimen were not observed and thought to be closer to the lip, like in Osteolepis and Diplopterus. On the labial margin of the snout Tristichopterus has small conical teeth. The aforementioned cranial shield on its posterior margin is composed of three parts: one mesial and polygonal in shape and two lateral, triangular in shape. These dermal bones are equivalent to transverse supral temporal chain elements in Polypterus and Lepidosteus. A large oblong plate covers a significant portion of the cheek in front of the opercular bones contacting the hind part of the maxilla. The plate articulates just in front of the orbit with a hyomandibular mechanism similar to Gyroptychius, possibly a pre operculum. The orbit itself is placed very far forward on the skull. [3]

Tristichopterus has a lower jaw is as long as its cranium proper and its operculum, on its anterior margin, is inclined down and back. The maxilla abuts below the cheek plate and suborbitals and is a long narrow bar that widens slightly at its posterior and at its anterior is capped with a small premaxilla. Long, robust and slenderer than Saurodipterini the lower jaw from the side is seen as straight but from the front it curves inwards to the symphysis. On its lower jaw, Tristichopterus has two stout sharp conical teeth 1/8 inch in length by 1/16 in diameter at base. All teeth are slightly incurved, with fluting at bottom of larger teeth. A pulp cavity was observed to reach the central cavity in most teeth.[3] Notably, Tristichopterus, like Eusthenopteron, lacks dentary fangs which are present in all other tristichopterids.[9]

The shoulder girdle of Tristichopterus has no distinct attachment to the skull, but sports a stout broad oblong plate in place of a clavicle and shows evidence of a second supra-clavicular. The pectoral fin is large and obovately shaped like a fan with its terminus rounded and consisting of the aforementioned slender rays. The fin is characterized by a central scaled lobe half its length and bifurcates soon after its origin, divided by transverse articulations as it repeats frequently.[3]

Tristichopterus has its first dorsal opposite its ventrals, small and narrow, elliptic lanceolate in shape. The second dorsal is larger and expanded triangular form, closely proportioned to the anal. The caudal fin is again the previously written intermediate between a diphycercal and a heterocercal tail, also large and fan shaped and sports the stoutest fin rays in the entire structure. [3]

The scales of the body are thin and rounding. They are of decent size and show a deeply imbricating, exposed surface, ornamented by striae that are closely set and raised. The scales of lateral line may be perforated by a slime canal and notched posteriorly.[3]

The vertebral column of Tristichopterus is made up of osseous members with distinct neural arches that pass upward into spines. These spines flatten out laterally towards the front of the body. Supporting the second dorsal and anal fins is a large flattened bony pieces that could possibly be a composite spinous apophysis, resulting from a three spine union. Neurapophyseal ossicles support the anterior rays of the upper lobe of the caudal fin.[3]

References

- Bishop, P.J. 2012. A second species of Tristichopterus (Sarcopterygii: Tristichopteridae), from the Upper Devonian of the Baltic Region. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum – Nature 56(2): 305-309. Brisbane. ISSN 0079-8835. Accepted: 14 November 2012.

- Per E. Ahlberg & Zerina Johanson. 1997. Second tristichopterid (Sarcopterygii, Osteolepiformes) from the Upper Devonian of Canowindra, New South Wales, Australia, and phylogeny of the Tristichopteridae. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 17:4: 653-673.

- Traquair, R. 1875. On the Structure and Affinities of Tristichopterus alatus, Egerton. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 27: 383-396.

- Parfitt, Matthew & Johanson, Zerina & Giles, Sam & Friedman, Matt. 2014. A large, anatomically primitive tristichopterid (Sarcopterygii: Tetrapodomorpha) from the Late Devonian (Frasnian) Alves Beds, Upper Old Red Sandstone, Moray, Scotland. Scottish Journal of Geology. 50. 79-85. 10.1144/sjg2013-013.

- Whiteaves, J. 1883. Recent Discoveries of Fossil Fishes in the Devonian Rocks of Canada. The American Naturalist Vol 17 No. 2: 158-164.

- Traquair, R. 1890. Notes on the Devonian Fishes of Soaumenao Bay and Campbelltown in Canada. Geological Magazine: 7: 15-22.

- Sébastien Olive, Yann Leroy, Edward B. Daeschler, Jason P. Downs, Sandrine Ladevèze & Gaël Clément. 2020. Tristichopterids (Sarcopterygii, Tetrapodomorpha) from the Upper Devonian tetrapod-bearing locality of Strud (Belgium, upper Famennian), with phylogenetic and paleobiogeographic considerations. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 40:1: 1-53.

- "Flickr". January 1919.

- Downs, J.P., J. Barbosa, and E.B. Daeschler. 2021. A new species of Eusthenodon (Sarcopterygii, Tristichopteridae) from the Upper Devonian (Famennian) of Pennsylvania, U.S.A., and a review of Eusthenodon taxonomy. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 41(3): e1976197.

9. Traquair, R. (1875). 2. On the Structure and Systematic Position of Tristichopterus alatus, Egerton. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 8, 513-513. doi:10.1017/S0370164600030285 10. Young, G.C. 2008. Relationships of tristichopterids (osteolepiform lobe-finned fishes) from the Middle– Late Devonian of East Gondwana. Alcheringa 32, 321–336. ISSN 0311-5518.

.jpg.webp)