Hurricane Barry (2019)

Hurricane Barry was an asymmetrical Category 1 hurricane that was the wettest tropical cyclone on record in Arkansas and the fourth-wettest in Louisiana. The second tropical or subtropical storm and first hurricane of the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season, Barry originated as a mesoscale convective vortex over southwestern Kansas on July 2. The system eventually emerged into the Gulf of Mexico from the Florida Panhandle on July 10, whereupon the National Hurricane Center (NHC) designated it as a potential tropical cyclone. Early on July 11, the system developed into a tropical depression, and strengthened into a tropical storm later that day. Dry air and wind shear caused most of the convection, or thunderstorms, to be displaced south of the center. Nevertheless, Barry gradually intensified. On July 13, Barry attained its peak intensity as Category 1 hurricane with 1-minute sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 993 millibars (29.3 inHg). At 15:00 UTC, Barry made its first landfall at Marsh Island, and another landfall in Intracoastal City, Louisiana, both times as a Category 1 hurricane. Barry quickly weakened after landfall, falling to tropical depression status on July 15. The storm finally degenerated into a remnant low over northern Arkansas on the same day, subsequently opening up into a trough on July 16. The storm's remnants persisted for another few days, while continuing its eastward motion, before being absorbed into another frontal storm to the south of Nova Scotia on July 19.[1]

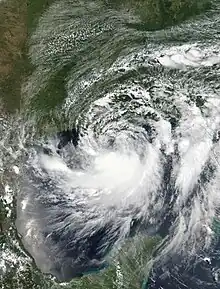

Barry shortly after making landfall in Louisiana at peak intensity on July 13 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | July 11, 2019 |

| Post-tropical | July 15, 2019 |

| Dissipated | July 19, 2019 |

| Category 1 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 75 mph (120 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 993 mbar (hPa); 29.32 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 3 total |

| Damage | $900 million (2019 USD) |

| Areas affected | Midwestern United States, Gulf Coast of the United States, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Eastern United States, Eastern Canada |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Barry was one of four hurricanes to strike Louisiana as a Category 1 hurricane in the month of July, the others being Bob in 1979, Danny in 1997, and Cindy in 2005.[2] Numerous tropical storm watches and warnings were issued for Mississippi and Louisiana ahead of the storm. Several states declared state of emergencies ahead of the storm. Though Barry only produced hurricane-force winds in a small area of Louisiana, more than 153,000 customers lost power in the state. As Barry drifted westward over the Gulf of Mexico, storm surge caused widespread coastal flooding in Alabama, Mississippi, and Alabama. The storm's large circulation produced heavy rainfall over a large area, reaching 23.43 in (595 mm) near Ragley, Louisiana, and 16.59 in (421 mm) near Dierks, Arkansas. The latter value was the highest amount of rainfall recorded in Arkansas related to a tropical cyclone. Many roads, including Interstate highways, were flooded. Dozens of water rescues were carried out in Louisiana and Arkansas, where the most significant flooding occurred. In parts of the Northeastern United States and Ontario, Canada, severe thunderstorms from Barry's remnants caused an additional 160,000 power outages and spawned a few weak tornadoes. The storm caused two fatalities: one in Florida from rip currents, and one in Connecticut from fallen trees and wires.[3][4] Damage from Barry was estimated to be about $900 million (2019 USD).

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The origins of Barry can be traced to a mesoscale convective vortex – a complex of thunderstorms – that formed over southwestern Kansas on July 2.[5] On July 5, the Climate Prediction Center noted the possibility for this disturbance to interact with a trough of low pressure over the Southeastern United States, eventually triggering the formation of a low pressure area over the Gulf of Mexico.[6] The following day, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) highlighted a low likelihood of tropical cyclogenesis while the disturbance was still centered well-inland over Tennessee, anticipating that the weather system would track into the northern Gulf of Mexico.[7] Over the next few days, the system drifted southeastward towards Georgia, steered by a low- to mid-level ridge to its west.[5] By July 8, the NHC assessed a high probability of a tropical cyclone developing due to favorable conditions in the Gulf.[8] On July 9, a broad area of low pressure exited the Florida Panhandle and tracked into the northeastern Gulf of Mexico, accompanied by scattered convection. It moved southwestward and curved to the west on the east side of the ridge.[5] On July 10, the NHC initiated advisories on the system as Potential Tropical Cyclone Two, due to its threat the system posed to the United States. At that time, the low pressure area was experiencing some northerly wind shear, which was expected to decrease. Sea surface temperatures of 86–88 °F (30–31 °C) allowed the system to gradually organize.[9]

At 00:00 UTC on July 11, the system developed into a tropical depression about 200 mi (320 km) south of Mobile, Alabama. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Barry six hours later as the convection had increased to the south of the system's circulation.[5] The storm's convection organized into a large rainband south of an elongated circulation,[10] though mid-level dry air and northerly wind shear prevented thunderstorms from forming near the center.[11][5] On July 12, data from two hurricane hunter reconnaissance aircraft found that Barry had quickly intensified, with its central pressure dropping.[12] Due to a slight decrease in shear on the morning of July 13, the storm's outflow expanded and the banding increased.[13] The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer instrument also found cloud tops colder than −80 °F (−62 °C) mostly south of the center.[14] Barry attained Category 1 hurricane status by 12:00 UTC that day, with a small area of hurricane-force winds occurring east of the center.[15] Simultaneously, the storm reached its peak intensity, with a minimum central pressure of 993 millibars (29.3 inHg).[5] At 15:00 UTC that day, Barry made landfall as a Category 1 hurricane on Marsh Island, Louisiana.[16] Barry was one of four hurricanes to hit Louisiana at Category 1 intensity in the month of July, the others being Bob in 1979, Danny in 1997, and Cindy in 2005.[2]

The storm quickly weakened after landfall, falling to tropical storm status late on July 13.[17] The storm moved slowly, leading to widespread flooding in Louisiana and Arkansas.[18] Barry further weakened to a tropical depression at 00:00 UTC on July 15 just south of the Louisiana-Arkansas border.[5] Satellite imagery showed that the cyclone had become elongated by that time.[19] At 12:00 UTC that same day, Barry degenerated into a remnant low over northern Arkansas. The remnant low continued to spin down and degenerated into a trough at 12:00 UTC a day later, over southern Missouri.[5] Over the next few days, Barry's remnants continued moving northeastward and then eastward, reaching Pennsylvania on July 18 and linking up with a cold front, and moving off the coast of Long Island late that day. On July 19, Barry's remnants were absorbed into another extratropical storm to the south of Nova Scotia.[1]

Preparations

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

On July 10, the NHC (which is part of the NOAA) began issuing various warnings and watches, including a hurricane watch for the Louisiana coast from Cameron to the Mississippi River Delta, a tropical storm watch from the Mississippi Delta to the mouth of the Pearl River, and a storm surge watch from the mouth of the Pearl River to Morgan City, Louisiana. After the disturbance became a tropical storm on July 11, the NHC issued a tropical storm warning from the mouth of the Pearl River to Morgan City, and a tropical storm watch eastward to the Mississippi/Alabama border, including the New Orleans metro area, Lake Pontchartrain, and Lake Maurepas. The agency also issued a storm surge warning from the mouth of the Atchafalaya River to Shell Beach, Louisiana.[5]: 20 On the afternoon of July 11, the National Hurricane Center issued a hurricane warning for coastal Louisiana between Intracoastal City to Grand Isle, Louisiana.[20] All tropical cyclone watches and warnings were discontinued at 21:00 UTC on July 14.[5]: 20 The NHC started giving emergency management direct support from July 9 to July 14. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Hurricane Liaison Team coordinated storm briefings to Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, along with FEMA regions 4 and 6. The Tropical Analysis and Forecast Branch of the NHC also assisted the U.S. Coast Guard in their operations during Barry.[5]: 8 More than 80 live briefings and 50 phone interviews were broadcast in local and national television. A total of 11 live briefings were also provided by the NHC on Facebook; those briefings received more than 400,000 views.[5]: 9

The National Weather Service issued severe thunderstorm watches and flash flood watches for several counties in Connecticut.[21]

Louisiana

.jpg.webp)

The United States Army Corps of Engineers feared that levees would be overtopped in Plaquemines Parish by storm surge and historically high river levels. Thus, a mandatory evacuation was ordered for the parish was implemented on the morning of July 11, affecting approximately 8,000–10,000 residents.[22] An evacuation order was issued for low-lying areas of Jefferson Parish;[23] the mayor of Grand Isle issued a mandatory evacuation as well. Due to the storm threat, the Carnival Valor changed its disembarking point from New Orleans to Mobile, Alabama.[24] Royal Dutch Shell evacuated non-essential personnel from its offshore oil platforms in the Gulf of Mexico.[25] Curfews were enacted in several Louisiana communities across five parishes on July 12.[26] New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell urged residents to "shelter in place" but did not order evacuations, citing Category 3 status as the threshold.[27]

.jpg.webp)

In a 24-hour span between July 10 and 11, 28 parishes issued emergency declarations. After declaring a state of emergency and deploying search and rescue assets,[28] Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards requested a federal disaster declaration for the entire state on July 11, citing the potential for widespread flooding;[29] the request was granted by President Donald Trump later that day.[30] On July 12, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar declared a public health emergency in Louisiana to prepare for Barry's potential impacts. In addition to making this declaration, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) worked with FEMA and positioned approximately 100 medical and public health personnel from various agencies, and provided medical equipment for medical teams.[31] On July 12, Mississippi Governor Phil Bryant declared a state of emergency, allocating state resources for storm relief and activating the state's emergency operations center.[32] The Mississippi Urban Search and Rescue Task Force dispatched two 12-person water rescue crews to Pike County and Camp Shelby to assist local emergency units.[33] Airbnb activated its Open Homes program, which provides temporary housing to evacuees or storm victims, for parts of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. Dozens of Airbnb hosts signed up to shelter displaced people and rescue workers.[34][35]

Impact

High water levels occurred from the Florida Panhandle to the upper Texas Coast.[5] Total economic losses from Barry are estimated at $600 million (2019 USD), with public and private insurers paying out nearly $300 million. More than 50,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed. Most of these losses were due to flooding along the Gulf Coast and in Arkansas.[36]

Louisiana

While Barry was in its formative stages, it dropped 6 to 9 in (150 to 230 mm) of rainfall across the New Orleans area, causing flooding.[37] An expansive thunderstorm inundated streets and businesses over a six-hour period on the morning of July 10.[38] Portions of the French Quarter were flooded and public transportation was disrupted. The impacts were exacerbated by an elevated Mississippi River amid a prolonged period exceeding flood stage.[39] Officials declared a flash flood emergency in New Orleans, as flooded streets forced businesses and government buildings to close.[40][39] A EF1 tornado was reported near New Orleans on July 10, snapping several trees and ripping the roof off a house; this tornado caused $300,000 in damage.[41]

When Barry made landfall, it produced hurricane-force winds in a small area near the Louisiana coast.[42] The strongest recorded sustained winds on land was 66 mph (106 km/h) at Acadiana Regional Airport in New Iberia.[5] In Iberia Parish, numerous trees were downed. The Dauterive Hospital lost power and both generators, and had to evacuate 60 patients in the middle of the storm.[43] For several days, Barry's intense rainbands affected the same portion of south-central and southwestern Louisiana. The highest rainfall total recorded along Barry's path was 23.43 in (595 mm) near Ragley.[5] Waterspouts were reported on Lake Pontchartrain.[40] A possible tornado damaged two homes when it struck the Gentilly neighborhood in New Orleans.[27] The highest storm surge in Louisiana was 6.13 ft (1.87 m) above normal tide levels at Eugene Island in Atchafalaya Bay. A tide station in Amerada Pass recorded a 6.93 ft (2.11 m) high tide, but the station had been recording higher than normal tides due to high runoff from the Mississippi River. On the southern shore of Lake Pontchartrain, the storm surge reached 4.3 ft (1.3 m).[5] Flooding occurred on the banks of the Atchafalaya River in Morgan City.[44] The Lower Dularge East Levee in Terrebonne Parish was overtopped, prompting a mandatory evacuation for nearby areas.[45] On the afternoon of July 12, Louisiana Highway 1 south of Golden Meadow was closed after seawater began to inundate portions of the road, cutting off access to Grand Isle and Port Fourchon.[46]

.jpg.webp)

A total of 153,000 customers lost power in Louisiana.[47] Power lines knocked down by fallen trees in the Metairie area cut power to 5,140 electricity customers in the New Orleans metropolitan area. The most widespread power outages occurred where wind speeds were highest in Lafourche Parish and Terrebonne Parish, as well as eastern Baton Rouge; over 39,000 lost power in these areas.[48] All electricity customers in Grand Isle lost power, and a total of 4,300 customers were affected by power outages as Barry's initial rainbands swept across coastal Louisiana.[49] Heavy rain from the storm caused The Rolling Stones to postpone their July 14 show at the Superdome to the next day.[50]

Remainder of the Gulf Coast

In Texas, wind gusts reached 56 mph (91 km/h) at Sabine Pass.[5] A peak rainfall amount of 4.61 in (117 mm) was recorded in Beaumont.[51] Five people were rescued 23 mi (37 km) southwest of Gulfport, Mississippi, after their ship ran aground.[52] On July 14, a brief EF0 tornado in Forrest County damaged a few tree limbs on its 0.48 mi (0.77 km) path.[53] A tornado warning was issued for Jackson County, though no tornadoes were reported in the county. Heavy rain occurred in southwestern Mississippi, and a rainfall amount of 13.30 in (338 mm) near Pass Christian.[51] The rains flooded roads near the coast, in conjunction with higher tides. Hurricane Barry produced a 3 ft (0.91 m) storm surge in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi.[5] Floodwaters inundated parts of Beach Boulevard in Pascagoula,[54] and closed roads in the Biloxi area. In West Jackson, flash flooding inundated a car and several streets on July 14, causing $20,000 in damage.[55] Ten roads were closed due to flooding in Newton County.[56] In Petal, Mississippi, more than 2 ft (0.61 m) of water covered roads, prompting road closures.[57] High winds and saturated soils led to fallen trees.[58] In Leesdale, near U.S. Highway 84, wind gusts up to 60 mph (96 km/h) brought down trees, blocking roads and intersections.[59] Severe thunderstorms from Barry's rainbands caused widespread tree damage across Adams County, causing $10,000 in damage.[60]

The outer rainbands of Barry dropped heavy rainfall in southern Alabama, reaching 8.36 in (212 mm) near Fairhope.[5] In Mobile County, several roads were underwater due to coastal flooding.[61] Torrential rainfall overwhelmed sewer systems in that city, with over 80,000 US gallons (300,000 L) of water spilling into streets. The storm forced the closure of popular beaches, including those in Orange Beach and Gulf Shores.[62] In southern Alabama, wind gusts reached 72 mph (116 km/h) on Pinto Island.[5] Around 2.8 ft (0.85 m) of storm surge was reported in coastal Alabama.[63] Floodwaters from coastal flooding reached several feet deep in some locations, causing beach erosion and leaving behind 3 ft (0.91 m) of sand on Bienville Boulevard on Dauphin Island. Floodwaters closed lanes of the Cochrane–Africatown USA Bridge in Mobile.[5][63]

The precursor disturbance to Barry caused severe thunderstorms across much of Florida. Numerous trees were blown down due to strong winds from downbursts.[64][65][66] In Garden City, a tree was blown down on Interstate 295 in a microburst.[67] Along the Florida Panhandle, beaches issued warnings to the public to stay out of the water to avoid rip currents and dangerous swimming conditions; however, there were still many calls of swimmers in distress. In Panama City Beach, multiple people formed a human chain in an effort to save swimmers who had gotten caught in a rip current caused by the storm. Authorities performed 38 water rescues. A 67-year-old man drowned in the waters.[3] Barry's large circulation produced gale-force wind gusts along the Gulf Coast as far east Panama City Beach, which recorded gusts of 41 mph (67 km/h).[5]

Arkansas

Following up to 8 in (200 mm) of rainfall, the National Weather Service issued a rare flash flood emergency at 5 a.m. CDT on July 16, for southern Pike and southern Clark counties.[68] Later, water rescues and washed-out roads were reported in Hempstead, Howard, and Nevada counties,[51] prompting a flash flood emergency to be issued for those counties as well.[68] At least 13 high water rescues were performed throughout the state. Howard County sustained the most significant and widespread flooding, with at least 30–40 structures damaged by flash flooding. Numerous roads and bridges were washed out in Hempstead and Nevada counties, including state and U.S. highways. In Hempstead County, 20 roads were washed out or damaged.[69] A portion of Interstate 30 was closed in Clark County due to flooding.[51] The Clark County Humane Society in Arkadelphia was drenched by floodwaters, killing a puppy. Later, the remaining animals were rescued.[70] A woman was rescued from fast-moving floodwaters in the same area.[71] In Nashville, the police department building and the county jail were damaged by flash flooding, and inmates had to be evacuated.[68] Several roads were underwater and closed in the city.[69] A part of Arkansas Highway 29 was flooded in Pike County.[72] Numerous cars were flooded and swept away in Dierks, along with flood damage to many buildings and the loss of over 200 head of cattle.[69] A rainfall total of 16.59 in (421 mm) was recorded near the city, making Barry the wettest tropical cyclone in state history.[73]

Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States

In the Northeastern United States, Barry worsened a heat wave due to the tropical air mass it brought along with it.[18] Barry's remnant moisture brought severe thunderstorms to the region from July 16–17, causing downed trees and power outages. Trees were reported down and power outages occurred in Ewing, New Jersey.[74] A portion of the Garden State Parkway was closed briefly due to flooding. Rome, New York, received more than 3 in (76 mm) of rain. On July 17, two people were injured in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, due to strong winds.[75] Lightning struck a cottonwood tree, which brought down wires and fell on a car in Southington. A 21-year-old man was killed. Numerous towns experienced power outages, with nearly 1,400 customers losing power in Fairfield. The outages also closed a library in Monroe.[4] Overall, 160,000 customers lost power due to the storms in the Mid-Atlantic and New England.[75] A MLB game at Yankee Stadium between the Tampa Bay Rays and New York Yankees was postponed due to the storm.[76]

Elsewhere

In Missouri, a peak rainfall amount of 5.35 in (136 mm) was recorded in Poplar Bluff, and in Tennessee, a peak amount of 6.09 in (155 mm) was recorded near Cookeville.[51] More than 2.4 in (60 mm) of rain fell in Toronto, Canada, on July 17, as the post-tropical cyclone moved just south of the area, resulting in street-level flash flooding and the blockage of a ramp to Ontario Highway 401, where several cars were submerged.[77] The city recorded its highest daily rainfall total in the month of July since 2013.[78] The storms also produced a funnel cloud in Oro-Medonte.[77] In Indianapolis, Indiana, over an inch of rainfall was recorded.[79]

Aftermath

In the immediate aftermath of the storm, flooding and storm surge washed wild animals into people's homes. In St. Tammany Parish, a large den of snakes entered people's homes and property. A video shared on social media showed an alligator entering a home in Livingston Parish.[80] On July 14, the United States Department of Labor announced efforts to help victims of Barry, according to Secretary of Labor Alexander Acosta.[81] Governor of Louisiana John Bel Edwards traveled to coastal Louisiana on July 15 to inspect damage from the storm. He visited Myrtle Grove, near Port Sulphur, where roads were damaged by floods. The governor later said in a news conference that the storm was not as bad as originally anticipated, but urged residents to prepare for later storms.[3] Mayor of Houston Sylvester Turner called New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell and offered to provide donations to affected areas through the Houston Relief Hub.[82] However, Cantrell said that her city of New Orleans was "beyond lucky" and was ready to help other parishes that got hit harder.[83] Many oil platforms and drilling companies in the northern Gulf of Mexico were heavily affected by the storm. The Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement asserted that Barry caused nearly 73% of crude oil production in the Gulf to shut on July 15, two days after the storm made landfall. About 62% of natural gas production had also ceased.[47]

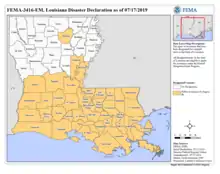

From July 25 to August 8, FEMA, along with state and local governments conducted Preliminary Damage Assessments in Louisiana.[84][85] On August 14, Governor John Bel Edwards requested a post-storm major disaster declaration for seven parishes,[84] which President Donald Trump granted on August 27.[86] The same day, Governor John Bel Edwards announced that the Governor's Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness and FEMA had recently completed damage assessments in the impacted areas.[85] Total cost for public assistance cost a little more than $16 million in Louisiana.[84]

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 2019

- Other storms named Barry

- List of Category 1 Atlantic hurricanes

- 1940 Louisiana hurricane – Produced flooding rainfall over southern Louisiana due to its slow movement

- 1943 Surprise Hurricane – The first hurricane to be observed by Hurricane Hunters, taking a similar westward path

- Hurricane Bonnie (1986) – A Category 1 hurricane that took a similar track to Barry's

- Hurricane Danny (1997) – Storm with similar origins that struck the Gulf Coast

- Tropical Storm Lee (2011) – Affected similar areas with significant flooding

- Hurricane Isaac (2012) – A Category 1 hurricane that made landfall in a similar location along the Gulf Coast

- Tropical Storm Cindy (2017) – A tropical storm that took a similar track to Barry's

- Hurricane Ida (2021) – A Category 4 hurricane that affected similar areas, namely the Gulf Coast and the Northeastern United States

References

- Hurricane Barry – July 7–18, 2019. www.wpc.ncep.noaa.gov (Report). Weather Prediction Center. January 25, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- Mitchell, Chaffin; Navarro, Adriana (July 14, 2019). "First Hurricane Landfall of the Season Leaves Louisiana, Mississippi waterlogged". Accuweather. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- Adams, Char (July 15, 2019). "Good Samaritans Form Human Chain to Rescue Swimmers from Rip Current in Florida". People Magazine. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - Fry, Ethan (July 17, 2019). "Man dies after wires, tree fall on vehicle on Fairfield-Bridgeport line". Connecticut Post. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- John Cangialosi; Andrew Hagen; Robbie Berg (November 18, 2019). Hurricane Barry Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 22, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- Morgan, Leigh (July 5, 2019). "Could Midwest storms help spawn a tropical storm in the Gulf next week?". Birmingham, Alabama: Alabama Media Group. Archived from the original on July 5, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- Blake, Eric S. (July 6, 2019). Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook [Atlantic 200 PM EDT Sat Jul 6 2019] (Report). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- Latto, Andrew; Pasch, Richard (July 8, 2019). Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook [Atlantic: 200 AM EDT Mon Jul 8 2019] (Report). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- Stewart, Stacy (July 10, 2019). Potential Tropical Cyclone Two Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- Beven, Jack (July 11, 2019). Tropical Storm Barry Discussion Number 5 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- Lixion, Avila (July 12, 2019). Tropical Storm Barry Discussion Number 8 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- Beven, Jack (July 12, 2019). Tropical Storm Barry Discussion Number 9 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- Daniel, Brown (July 13, 2019). Tropical Storm Barry Discussion Number 11 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- Gutro, Rob (July 13, 2019). NASA Sees Heavy Rainfall Potential in Strengthening Tropical Storm Barry (Report). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- Beven, Jack (July 13, 2019). Hurricane Barry Discussion Number 13 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- Beven, Jack (July 13, 2019). Tropical Storm Barry Discussion Number 13 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Beven, Jack (July 13, 2019). Tropical Storm Barry Intermediate Advisory Number 13A (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- State of the Climate: Hurricanes and Tropical Storms for July 2019 (Report). NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. August 2019. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- Gutro, Rob (July 15, 2019). Update #1 – NASA-NOAA Satellite Tracking Barry Through Louisiana, Arkansas (Report). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- Beven, Jack (July 11, 2019). Tropical Storm Barry Advisory Number 6 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- Shay, Jim (July 17, 2019). "Before Heat Wave, T-storms and Showers Moving In". Connecticut Post. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- Roberts, Faimon (July 10, 2019). "Mandatory evacuation in Plaquemines: Order to leave East Bank goes into effect Thursday". The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate. New Orleans, Louisiana. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- Williams, Jessica (July 11, 2019). "Mandatory evacuation for lower-lying areas of Jefferson Parish: 'People's lives are more important'". The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate. New Orleans, Louisiana. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- "The Latest: Tropical Storm Barry Forms in the Gulf". The Minneapolis Star-Tribune. Associated Press. July 11, 2019. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- Mcauley, Anthony (July 9, 2019). "Shell evacuates non-essential staff from Gulf of Mexico platforms as Invest 92L storm brews". The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate. New Orleans, Louisiana. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- "Curfews Set for Acadiana". KATC News. Acadiana, Louisiana: The E.W. Scripps Co. July 12, 2019. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- Williams, Jessica (July 11, 2019). "New Orleans officials give updates, warnings on Tropical Storm Barry prep; issue no evacuation orders". The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate. New Orleans, Louisiana. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- McWhriter, Cameron; Calfas, Jennifer (July 11, 2019). "Tropical Storm Barry Brews, Forcing Evacuations". The Wall Street Journal. New York City: Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.(subscription required)

- Edwards, John Bel (July 11, 2019). "Archived copy" (PDF). Office of the Governor. Letter to Trump, Donald J. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Office of the Governor of Louisiana. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

{{cite press release}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Mumphrey, Nicole (July 12, 2019). "President Trump Approves Emergency Declaration for Louisiana Ahead TS Barry". New Orleans, Louisiana: FOX 8. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- "HHS Secretary Azar Declares Public Health Emergency in Louisiana Due to Tropical Storm Barry" (Press release). United States Department of Health and Human Services. July 12, 2020. Archived from the original on October 14, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- Foxx, Keegan (July 12, 2019). "Mississippi Governor Declares State of Emergency Ahead of Barry". WAPT-TV. Jackson, Mississippi: Hearst Television Inc. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- Jackson, Ann (July 12, 2019). "State Agencies are Positioning Resources Ahead of Tropical Storm Barry's Arrival". WLBT. Jackson, Mississippi. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- Gibson, Raegen (July 12, 2019). "Airbnb to Offer 'Open Homes' Program, Free Housing to Some Louisiana Evacuees as Tropical Storm Barry Approaches". KBMT. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- "Airbnb to Help Victims of Tropical Storm Barry". KRIV. July 12, 2019. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- Global Catastrophe Recap July 2019 (PDF) (Report). AON. August 8, 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 16, 2019. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- Stewart, Stacy (July 10, 2019). Potential Tropical Cyclone Two Intermediate Advisory Number 1A (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- "New Orleans flooding caused by sudden rain in what might be 'a taste of what could occur'". The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate. New Orleans, Louisiana. July 9, 2019. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- Breslin, Sam (July 10, 2019). "New Orleans Flash Flood Emergency: Streets Inundated, City Offices Closed". Atlanta, Georgia: The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- Livingston, Ian (July 10, 2019). "New Orleans Just Faced a Flash Flood Emergency, and Barry Could Bring More Severe Flooding Saturday, Testing Levees". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.(subscription required)

- Event: Tornado in New Orleans, LA [2019-07-10 07:26 CST-6] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Lamers, Alex (July 16, 2019). Post-Tropical Cyclone Barry Advisory Number 25 (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- Event: Hurricane in Iberia Parish, LA [2019-07-13 05:00 CST-6] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Sosnowski, Alex. "Barry Threatens Lower Mississippi Valley With Significant Flooding, Isolated Tornadoes Into Monday". Accuweather. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- Sledge, Matt (July 13, 2019). "Overtopped Levee in Terrebonne Prompts Partial Evacuation; people, Cat Rescued from Cut Off Island". The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate. New Orleans, Louisiana. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- "La. 1 Closed South of Golden Meadow". Houma Today. July 12, 2019. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- Ling, Danielle (July 15, 2019). "Cleanup Begins After Barry, First Hurricane of the Season, Hits Louisiana". PropertyCasualty360. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- Mcauley, Anthony; Haselle, Della (July 13, 2019). "As Hurricane Barry rolls in, over 114,000 Louisiana customers without power, some areas inaccessible". New Orleans, Louisiana: The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- Brennan, Sean (July 12, 2019). "Outages: Grand Isle Power Knocked as Storm Nears, Thousands Without Power in Jefferson, Terrebonne Parishes". New Orleans, Louisiana: WWL-TV. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- Holcombe, Madeline (July 13, 2019). "Rolling Stones' concert postponed as Tropical Storm Barry nears landfall". CNN. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- "Hurricane Barry Struck the Gulf Coast and Caused Flooding From Louisiana Into Arkansas (RECAP)". The Weather Channel. July 18, 2019. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- Beveridge, Lici (July 12, 2019). "Coast Guard Aircrew Rescues 5 People in Gulf as Tropical Storm Barry Gathers Steam". Jackson, Mississippi: The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved July 12, 2019.(subscription required)

- Event: Tornado in Forrest, MS [2019-07-14 05:25 CST-6] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- Event: Storm Surge/Tide in Jackson, Mississippi [2019-07-11 21:00 CST-6] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- Event: Flash Flood in West Jackson, MS [2019-07-14 04:54 CST-6] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Event: Flash Flood in Newton, MS [2019-07-15 05:00 CST-6] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Event: Flash Flood in Petal, MS [2019-07-14 07:24 CST-6] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Johnson, Annie (July 13, 2019). "Areas of South Mississippi Seeing Impacts of Hurricane Barry". WLOX. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- Event: Thunderstorm Wind in Leesdale, MS [2019-07-14 07:45 CST-6] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Event: Thunderstorm Wind in Adams County, MS [2019-07-14 01:30 CST-6] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Event: Coastal Flooding in Mobile, Alabama [2019-07-12 06:00 CST-6] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Vollers, Anna Claire (July 14, 2019). "Hurricane Barry Leaves Flooding, Sewer Overflows, Closed Beaches in its Wake". Advance Local. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- Barry, Morgan; Maniscalco, Joe (2019). Hurricane Barry – July 13, 2019 (Report). Mobile-Pensacola National Weather Service. Archived from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- Event: Thunderstorm Wind in Bakersville, FL [2019-07-11 16:23 EST-5] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Event: Thunderstorm Wind in Palmo, FL [2019-07-11 16:31 EST-5] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Event: Thunderstorm Wind in East Mandarin, FL [2019-07-11 16:48 EST-5] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Event: Thunderstorm Wind in Garden City, FL [2019-07-11 17:21 EST-5] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Heavy Rain/Flooding with Barry on July 14–17, 2019. National Weather Service Little Rock, Arkansas (Report). July 18, 2019. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- Event: Flash Flood in Nashville, AR [2019-07-16 03:57 CST-6] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Bacon, John (July 16, 2019). "Humane Society SOS: Dogs Swim For Their Lives as Ark. Shelter Floods. Community Comes To The Rescue". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 17, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- Brackett, Ron (July 16, 2019). "Barry Impacts: Flooding Swamps Arkansas Police Station and Animal Shelter; Washes Out Highways". The Weather Company. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- Event: Flash Flood in Pike County, AR [2019-07-16 04:37 CST-6] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Climatic Data Center. 2019. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Jeromin, Kerrin (July 16, 2020). "Arkansas 5th State Since 2017 to Get Record Tropical Rain". WeatherNation TV. Archived from the original on July 23, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- "Barry Remnants Leave Power Out, Trees Down in New Jersey". NBC 10 Philadelphia. July 18, 2019. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- Sosnowski, Alex (July 17, 2019). "Barry Still Packing a Punch with Heavy Thunderstorms, Flooding Downpours". Accuweather. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- Rays-Yankees game postponed due to severe weather forecast, Fox 35 Orlando, July 17, 2019

- Sonnenbury, Kelly (July 17, 2019). "IN PHOTOS: Funnel clouds, flash flooding, more storms ahead". Pelmorex Media. The Weather Network. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- Hamilton, Tyler (July 17, 2019). "Toronto just had its rainiest July day in over half a decade". Pelmorex Media. The Weather Network. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- History of Tropical Cyclone Remnants for Central Indiana (Report). National Weather Service Indianapolis, Indiana. 2019. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- Billings, Kevin (July 15, 2019). "Hurricane Barry Aftermath: Flooding, Tornadoes, And Snakes A Threat In Storm's Wake". International Business Times. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Weeks, Emily (July 14, 2019). "U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR ANNOUNCES ACTIONS TO ASSIST AMERICANS IMPACTED BY HURRICANE BARRY" (Press release). United States Department of Labor. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- Kirk, Bryan (July 13, 2020). "Hurricane Barry: Houston Taking Donations For Storm Victims". Patch Media. Archived from the original on October 13, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- "Barry Spares New Orleans but Fuels Fears of Floods and Tornadoes". The Guardian. July 14, 2019. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- Preliminary Damage Assessment Report Louisiana–Hurricane Barry FEMA-4458-DR (PDF) (Report). FEMA. August 27, 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- Jacobs, David (August 27, 2020). "Federal Government Agrees to Help Pay for Louisiana's Recovery from Hurricane Barry". The Center Square. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- "President Donald J. Trump Approves Louisiana Disaster Declaration". whitehouse.gov (Press release). The White House. August 27, 2020. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2020 – via National Archives.

External links

- The National Hurricane Center's advisory archive on Hurricane Barry

- The Weather Prediction Center's advisory archive on Hurricane Barry

- The Weather Prediction Center's storm summaries on Barry