1975 Atlantic hurricane season

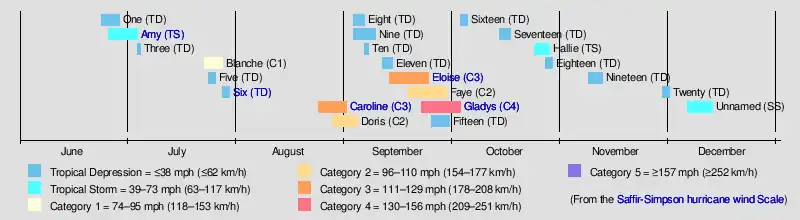

The 1975 Atlantic hurricane season was a near average hurricane season with nine named storms forming, of which six became hurricanes. Three of those six became major hurricanes, which are Category 3 (130 mph (209 km/h) sustained winds) or higher systems on the Saffir–Simpson scale. The season officially began on June 1 and lasted until November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic Ocean.

| 1975 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 24, 1975 |

| Last system dissipated | December 13, 1975 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Gladys |

| • Maximum winds | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 939 mbar (hPa; 27.73 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 23 |

| Total storms | 9 |

| Hurricanes | 6 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 87 total |

| Total damage | $564.7 million (1975 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The first system, Tropical Depression One, developed on June 24. Tropical Storm Amy in July caused minor beach erosion and coastal flooding from North Carolina to New Jersey, and killed one person when a ship capsized offshore North Carolina. Hurricane Blanche brought strong winds to portions of Atlantic Canada, leaving about $6.2 million (1975 USD) in damage. Hurricane Caroline brought high tides and flooding to northeastern Mexico and Texas, with two drownings in the latter.

The most significant storm of the season was Hurricane Eloise, a Category 3 hurricane that struck the Florida Panhandle at peak intensity, after bringing severe flooding to the Caribbean. Eloise caused 80 fatalities, including 34 in Puerto Rico, 7 in Dominican Republic, 18 in Haiti, and 21 in the United States, with 4 in Florida. The hurricane left about $560 million in damage in the United States. Hurricane Gladys, a Category 4 hurricane, was the most intense tropical cyclone of the season, but left little impact on land. Also, it was the first tropical storm to be upgraded to a hurricane based solely on satellite imagery.[1] Two tropical depressions also caused damage and fatalities. Collectively, the tropical cyclones of this season resulted in 87 deaths and about $564.7 million in damage.

Season summary

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1,[2] with the first tropical cyclone developing on June 24. Although 23 tropical depressions developed, only nine of them reached tropical storm intensity;[3] this was near normal compared to the 1950–2000 average of 9.6 named storms.[4] Six of these reached hurricane status,[3] slightly above the 1950–2000 average of 5.9.[4] Furthermore, three storms reached major hurricane status;[3] above the 1950–2000 average of 2.3.[4] Collectively, the cyclones of this season caused at least 84 deaths and over $564.7 million in damage.[5] The Atlantic hurricane season officially ended on November 30,[2] though the final cyclone became extratropical on December 13.[3]

Tropical cyclogenesis began in June, with the development of a tropical depression on June 24, followed by Tropical Storm Amy on June 27. Four systems originated in July, including Hurricane Blanche. After Tropical Depression Six dissipated on July 30, tropical activity went dormant for over three weeks, ending with the development of Hurricane Caroline on August 24. Another cyclone, Hurricane Doris, also formed in August. September was the most active month of the season, featuring eight tropical cyclones, including hurricanes Eloise, Faye, and Gladys. In October, four systems formed, one of which intensified into Tropical Storm Hallie. Two tropical depressions developed in November. The last system, a subtropical storm, formed on December 6 and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on December 13.[3]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 76.[6] Broadly speaking, ACE is a measure of the power of a tropical storm multiplied by the length of time it existed. Therefore, a storm with a longer duration will have high values of ACE. It is only calculated for full advisories on specific tropical and subtropical systems reaching or exceeding wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h). Accordingly, tropical depressions are not included here. After the storm has dissipated, typically after the end of the season, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) reexamines the data. These revisions can lead to a revised ACE total either upward or downward compared to the operational value.[6]

Systems

Tropical Storm Amy

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 27 – July 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 981 mbar (hPa) |

A trough of low pressure developed into a tropical depression while just north of Grand Bahama on June 27.[3][7] The depression headed generally northward and remained weak. Upon nearing the coast of the Carolinas, the depression turned sharply eastward ahead of a rapidly approaching trough. Early on June 29, the system intensified into Tropical Storm Amy offshore North Carolina. Further intensification occurred and the storm reached its peak intensity with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 981 mbar (981 hPa; 29.0 inHg) by July 2.[3] During most of the storm's existence, Amy featured many subtropical characteristics – both tropical and extratropical characteristics – but was not classified as such due to the proximity to land.[7] By July 4, the system moved southeast of Newfoundland before becoming extratropical. The remnants continued rapidly northeastward and soon dissipated.[3]

The main effects from Amy were rough seas, reaching up to 15 ft (4.6 m) in height, that were felt from North Carolina to New Jersey, inflicting minor coastal flooding and beach erosion.[7][8] The storm also brought generally light rainfall to land, peaking at 5.87 in (149 mm) in Belhaven, North Carolina.[9] Offshore North Carolina, a schooner carrying four people capsized on June 30, resulting in the death of the father of the other three crew members. They remained at sea for roughly 15 days before being rescued by a Greek merchant ship.[10]

Hurricane Blanche

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 24 – July 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 980 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic Ocean from the west coast of Africa on July 14. The system remained weak for about a week, before convection began increasing significantly on July 21. After wind shear decreased,[7] the wave managed to develop into a tropical depression on July 24 about 355 miles (571 km) northeast of the Turks and Caicos Islands. It moved northwestward until early on July 26,[3] when an approaching cold front and associated trough caused the depression to turn northeastward.[7] Around that time, the cyclone intensified into Tropical Storm Blanche.[3] A weakening cold front and baroclinic forces created an environment favorable for intensifying,[7] allowing Blanche to become a Category 1 hurricane on July 27. Slightly further deepening occurred, with the storm peaking with winds of 85 mph (137 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 980 mbar (29 inHg). Before 12:00 UTC on July 28, Blanche made landfall in Barrington, Nova Scotia, with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). The system quickly transitioned into an extratropical cyclone, which soon dissipated.[3]

In Atlantic Canada, the remnants of Blanche produced high winds gusts up to 70 mph (110 km/h), along with moderate rainfall, peaking at 3.1 in (79 mm) in Chatham, New Brunswick.[11] The strong winds knocked over two mobile homes and destroyed a slaughterhouse, which was under construction. Additionally, trees and power lines were downed, leaving between 500 and 1,000 customers without electricity. The electrical corporation in Nova Scotia suffered about $196,600 in damage. Telephone services were also interrupted. The A. Murray MacKay Bridge was closed after an oil rig broke loose and threatened to strike the bridge. In Prince Edward Island, flights to and from the Charlottetown Airport were canceled, as was ferry service to Nova Scotia. In the province, many homes and businesses lost telephone service. Overall, damage in Canada reached about $6.2 million.[12]

Tropical Depression Six

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 27 – July 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); |

Tropical Depression Six developed from a trough of low pressure in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico about 60 mi (97 km) southwest of Cape San Blas, Florida, on July 27.[3][7] The depression moved west-northwestward and strengthened slightly to reach winds of 35 mph (56 km/h), but remained below tropical storm intensity and made landfall in eastern Louisiana. Once inland, the depression slowly weakened and re-curved northwestward on July 30 into Mississippi. Around that time, the depression dissipated.[3] The remnants persisted at least until August 3, at which time it was situated over Arkansas.[13]

The tropical depression dropped heavy rainfall, with some areas of the Florida Panhandle experiencing more than 20 in (510 mm) of precipitation, with a maximum total of 20.84 in (529 mm) observed in DeFuniak Springs.[9] Bay, Gulf, Holmes, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, Wakulla, and Walton were hardest hit. Numerous roads were flooded and closed, with $3.2 million in damage to that infrastructure. About 500 homes suffered flood damage, 22 of which were destroyed. Damage is estimated to have reached $8.5 million in the state of Florida alone.[14] In southern Alabama, overflowing rivers flooded several businesses and homes in Brewton and East Brewton. Damage in Alabama totaled approximately $300,000.[15] In Mississippi, about 50 families in the vicinity of the Biloxi River were evacuated as the river threatened to exceed its banks,[16] while at least 70 families fled their homes in Moss Point. Water entered about a dozen homes there. Further north, about 100 residences were evacuated in Canton, where some businesses suffered water damage. A total of 12 homes in Vicksburg were flooded.[16] The storm left three fatalities, with two in Florida and one in Alabama.[17][18]

Hurricane Caroline

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 24 – September 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); 963 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave that emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on August 15 developed into a tropical depression about 200 mi (320 km) north of Hispaniola on August 24.[3][7] The depression moved west-southwestward and failed to intensify before crossing the Turks and Caicos Islands and making landfall along the northern coast in eastern Cuba on August 25. After emerging into the Caribbean Sea, the cyclone headed west-northwestward beginning on August 27. By the following day, the depression entered into the Gulf of Mexico after passing just offshore the Yucatán Peninsula. The system then intensified into Tropical Storm Caroline early on August 29 and hurricane by 00:00 UTC the following day. Further strengthening occurred, with the storm peaking as a Category 3 hurricane with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 963 mbar (28.4 inHg) early on August 31. Around that time, Caroline made landfall in a rural area of Tamaulipas, located in northeastern Mexico. The system rapidly weakened and dissipated on September 1.[3]

In Mexico, the storm produced 10 ft (3.0 m) storm tides along the coast, while 5–10 in (130–250 mm) of rain fell inland. Flooding rains forced 1,000 people to evacuate and left moderate damage to homes and businesses. The precipitation ended an eight-month drought that was affecting inland portions of northern Mexico and decreasing the area's corn production.[19] Along the coast, several small villages sustained significant damage from the hurricane's storm surge.[20] Portions of south Texas also experienced heavy rainfall, with 11.93 in (303 mm) at Port Isabel.[9] Brownsville broke a record for the highest amount of precipitation observed on a day in August.[21] Two deaths occurred from drowning in Galveston.[22]

Hurricane Doris

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 28 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min); 965 mbar (hPa) |

A low pressure area developed within a frontal band over the central Atlantic on August 27.[7] At 12:00 UTC on the following day, the system developed into a subtropical storm while situated 930 mi (1,500 km) southwest of the Azores.[3] The subtropical classification was due to the lack of a central dense overcast (CDO), with the showers and thunderstorms mainly consisting of a strong band of convention located southeast of the center, as well as its association to the frontal band. Because the system was out of the authorized range of reconnaissance aircraft flights, satellites and ships were used to monitor the storm's intensity and tropical status. After satellite imagery indicated that the system became more symmetrical, developed CDO, and detached from the frontal system,[7] the cyclone was reclassified as Tropical Storm Doris on August 29.[3]

Doris made meteorological history when, on August 31, it became the first Atlantic hurricane ever to be upgraded to hurricane intensity solely on the basis of satellite pictures,[1] via the Dvorak technique.[7] The cyclone then curved northward and intensified further during the next few days, becoming a Category 2 hurricane early on September 2.[3] Based on the Dvorak technique, it is estimated that Doris peaked with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (180 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 965 mbar (28.5 inHg) shortly thereafter. By September 3, the hurricane began interacting with a non-tropical low pressure area.[7] On the following day, Doris quickly weakened to a tropical storm and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone about 830 mi (1,340 km) south-southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland, around 06:00 UTC. The extratropical remnants weakened and then dissipated late on September 4.[3]

Hurricane Eloise

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 13 – September 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min); 955 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression on September 13 to the east of the Virgin Islands.[3][7] The system tracked westward and strengthened into Tropical Storm Eloise while passing to the north of Puerto Rico. Eloise briefly reached hurricane intensity soon thereafter, but weakened back to a tropical storm around landfall over Hispaniola. The cyclone emerged into open waters of the northern Caribbean Sea. After striking the northern Yucatán Peninsula, Eloise turned northward and re-intensified. In the Gulf of Mexico, the cyclone quickly deepened, becoming a Category 3 hurricane on September 23. The hurricane made landfall west of Panama City, Florida, before moving inland across Alabama and dissipating on September 24.[3]

The storm produced heavy rainfall throughout Puerto Rico and Hispaniola,[7] causing extensive flooding that left severe damage 59 fatalities.[23] Thousands of people in these areas became homeless as flood waters submerged numerous communities.[24] As Eloise progressed westward, it affected Cuba to a lesser extent.[25] In advance of the storm, about 100,000 residents evacuated from the Gulf Coast region.[23] Upon making landfall in Florida, Eloise generated wind gusts of 155 mph (249 km/h),[7] which demolished hundreds of buildings in the area. The storm's severe winds, waves, and storm surge left numerous beaches, piers, and other coastal structures heavily impaired.[23]

Wind-related damage extended into inland Alabama and Georgia.[7] Further north, torrential rains along the entire East Coast of the United States created an unprecedented and far-reaching flooding event, especially into the Mid-Atlantic States.[26] In that region, an additional 17 people died as a result of freshwater flooding from the post-tropical storm;[23] infrastructural and geological effects were comparable to those from Hurricane Agnes three years prior.[26] Across the United States, damage amounted to approximately $560 million.[7] The storm killed 80 people along its entire track.[23]

Hurricane Faye

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 18 – September 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 977 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on September 14. After detaching from the Intertropical Convergence Zone on September 18,[7] the wave quickly developed into a tropical depression about 575 mi (925 km) west of the Cabo Verde Islands.[3] Moving northwestward, the depression intensified, according to ships and satellite imagery,[7] becoming Tropical Storm Faye on September 19.[3] The cyclone then moved westward and was unable to intensify further due to increasing wind shear,[7] before weakening to a tropical depression on September 23.[3] Shortly thereafter, Faye turned to the north, crossing an upper trough axis over the central Atlantic. Southwesterly flow aloft allowed the system to re-strengthen,[7] with Faye becoming a tropical storm again on September 25. Faye accelerated to the northwest and deepened into a Category 1 hurricane early on September 26, several hours before reaching Category 2 intensity.[3]

Around 23:00 UTC on September 26, the cyclone passed about 35 mi (56 km) east of Bermuda. Winds up to 69 mph (111 km/h) and heavy rains were recorded on the island.[27] Up to 2.8 in (71 mm) of rain fell in Bermuda from the hurricane.[9] Already severely impacted by flooding from Eloise days earlier, New England prepared for additional flooding from Faye. The National Weather Service issued flash flood watches, resulting in more evacuations.[28] At 00:00 UTC on September 27, the hurricane reached its maximum sustained wind speed of 105 mph (169 km/h).[3] Later that day, Faye curved northeast under strong westerly flow.[7] Although the system weakened to a Category 1 hurricane late on September 28, the storm reached its minimum barometric pressure of 977 mbar (28.9 inHg),[3] observed by a reconnaissance aircraft.[7] Faye then curved eastward and lost tropical characteristics, becoming extratropical at 12:00 UTC on September 29, while situated northwest of Corvo Island in the Azores.[3]

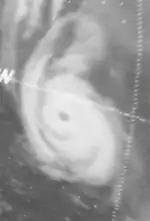

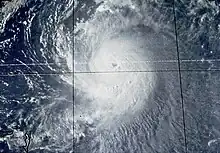

Hurricane Gladys

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 22 – October 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min); 939 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on September 17.[7] The system developed into a tropical depression while located about 750 mi (1,210 km) southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands on September 22.[3] Initially, the depression remained weak, but after encountering warm sea surface temperatures and low wind shear,[7] it strengthened into Tropical Storm Gladys on September 24.[3] Moving west-northwestward, the storm then entered a more unfavorable environment, mainly increased wind shear.[7] Despite this, Gladys intensified into a Category 1 hurricane on September 28.[3] Shortly thereafter, the storm reentered an area favorable for strengthening. A well-defined eye became visible on satellite imagery by September 30.[7]

As the storm tracked to the east of the Bahamas, a curve to the north began, at which time an anticyclone developed atop the cyclone.[7] This subsequently allowed Gladys to rapidly intensify into a Category 4 hurricane, reaching maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (230 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 939 mbar (27.7 inHg) on October 2. Thereafter, Gladys began to weaken and passed very close to Cape Race, Newfoundland, before losing tropical characteristics on October 3 while situated about 385 mi (620 km) northeast of St. John's.[3] Subsequently, the remnants merged with a large extratropical cyclone on October 3. Effects from the system along the East Coast of the United States were minimal, although heavy rainfall and rough seas were reported.[7] In Newfoundland, strong winds and light precipitation were observed.[29]

Tropical Depression Seventeen

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 14 – October 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical depression developed in the southern Gulf of Mexico about 125 mi (201 km) northwest of Campeche City in Mexico on October 14.[3] Moving around the western periphery of a subtropical ridge, the depression intensified while moving northeast towards the central Gulf Coast of the United States due to an advancing cold front.[30] However, the depression remained below tropical storm status, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 35 mph (56 km/h). Early on October 17, the depression made landfall near Cocodrie, Louisiana.[3] Shortly thereafter, the depression became an extratropical cyclone as it through the Southeast and Mid-Atlantic states, before moving offshore New England.[30]

Heavy rains fell along the frontal boundary ahead of the system,[30] with a peak total of 9.01 in (229 mm) of precipitation observed in Aimwell, Louisiana.[9] Flooding occurred across eastern Louisiana, central Mississippi, the western Florida Panhandle, central Tennessee, western Virginia, and eastern New York. In Jackson, Mississippi, the heavy precipitation established a new daily rainfall record for October 16 and a new 24-hour rainfall record for the month of October. Eight bridges were damaged in Jackson County, Tennessee, due to the floods. Heavy rains left heavy damage to the soybean and corn crops in Hickman and Marion counties in Tennessee. Six tornadoes were reported in association with this tropical depression, including two in Alabama, two in northwest Florida, and two in North Carolina. One person died due to flooding in Mississippi.[30]

Tropical Storm Hallie

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 24 – October 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1002 mbar (hPa) |

A frontal trough exited the East Coast of the United States on October 18. The southern portion of the system became stationary near the Bahamas; simultaneously, a cut-off upper-level low formed in the same region. The disturbance produced scattered convection, until a tropical wave merged with it on October 23. The system developed into a subtropical depression by October 24, while located about 100 mi (160 km) east of Florida. The depression drifted northward on October 25 and eventually acquired tropical characteristics by October 26. Due to tropical storm force winds, the system was reclassified as Tropical Storm Hallie, while situated about 100 mi (160 km) east of Charleston, South Carolina. Hallie accelerated to the northeast starting on October 26. By the following day, Hallie peaked with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h). Later that day, Hallie merged with a frontal zone and became extratropical offshore Virginia.[31][32]

The precursor to Hallie produced extensive cloudiness precipitation in the Bahamas.[33] On October 27, gale warnings were issued for portions of the Outer Banks of North Carolina, and small craft advisories were posted for coastal areas from Georgia to Virginia.[34] Tides along the North Carolina and Virginia coasts were generally between 1 and 2 ft (0.30 and 0.61 m) above normal. Generally light precipitation fell, peaking at 2.55 in (65 mm) in Manteo, North Carolina.[33] Additionally, the pressure gradient between Hallie and a high pressure area increased winds across much of the East Coast of the United States.[31]

Unnamed subtropical storm

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | December 9 – December 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 985 mbar (hPa) |

An extratropical low pressure system developed into a subtropical storm about 615 mi (990 km) east-southeast of Newfoundland, at 12:00 UTC on December 9.[3][7] The storm moved rapidly southward and intensified, reaching maximum sustained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) about 24 hours later,[3] based on observations from an unidentified ship.[7] Shortly thereafter, sustained winds began decreasing. However, late on December 11, the storm attained its minimum barometric pressure of 985 mbar (29.1 inHg). The system began moving southeastward and then eastward. By 12:00 UTC on December 12, the cyclone weakened to a subtropical depression. Moving northward, it dissipated 24 hours later, while situated about 505 mi (813 km) south-southwest of the Azores.[3]

Other systems

In addition to the named storms and notable tropical depressions, several other minor tropical depressions developed during the season. On June 24, the first tropical depression developed over the central Atlantic. It tracked westward for two days, before executing a counter-clockwise loop. By June 28, the system had completed the loop and was tracking north. The depression dissipated on June 29 about 305 mi (491 km) southeast of Sable Island, an island located southeast of Nova Scotia. A third tropical depression formed northeast of the Bahamas on July 4. Tracking northeastward, the system did not intensify and was last noted over open waters midday on July 5.[3] On July 24, the fifth tropical depression of the season formed over the southwestern Gulf of Mexico. Deep convection associated with the system persisted around the center of circulation.[7] Forecasters anticipated the depression would intensify into a tropical storm before landfall.[35] A reconnaissance mission into the cyclone found 50 mph (80 km/h) winds; however, due to the interaction with land, the NHC did not upgrade the depression. Not long after forming, the depression struck Tampico, Tamaulipas. A barometric pressure of 1,007 mbar (1,007 hPa; 29.7 inHg) was recorded in the city, along with sustained winds of 37 mph (60 km/h). The system was no longer monitored by the NHC after landfall and quickly dissipated on July 26.[7]

On September 3, two tropical depressions developed near Cabo Verde. The westernmost, designated Tropical Depression Eight, tracked generally westward and eventually dissipated near the Lesser Antilles on September 9. The easternmost, Tropical Depression Nine, also moved westward and dissipated on September 6. Another tropical depression developed near Bermuda on September 11. Initially, the depression drifted northeastward but later accelerated and dissipated by September 14.[3] Tropical Depression Fifteen developed near the Gulf of Honduras on September 25 and tracked slowly westward. By September 28, the depression made landfall in northern Belize before dissipating two days later. A tropical depression developed to the west of the Canary Islands on October 3, moving northwestward and then northeastward before dissipating southwest of the Azores on October 5. Tropical Depression Eighteen formed on October 27 over the southwestern Caribbean Sea and tracked northwest. After turning nearly due west, the depression briefly made landfall near the Nicaragua–Honduras border and made another landfall in southern Belize shortly before dissipating on October 29.[3] On November 8, a tropical depression developed off the coast of Honduras. Moving north-northwestward, the system gradually intensified. Between November 9 and 10, reconnaissance missions into the depression found winds of 40 mph (64 km/h); however, the NHC did not upgrade it to a tropical storm, because weaken occurred shortly thereafter. Over the following few days, the system gradually turned southward and made landfall in the southwestern edge of the Yucatán Peninsula on November 12, shortly before dissipating. In late November, another tropical depression formed over the central Atlantic. A short-lived system, it formed on November 29 and dissipated on December 1.[3]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms (tropical storms and hurricanes) that formed in the North Atlantic in 1975.[36] Storms were named Amy, Caroline, Doris, Eloise and Faye for the first time in 1975. The unused names Ingrid, Julia, Opal, and Vicky were later put onto modern naming lists. Names that were not assigned are marked in gray.

|

|

Retirement

The name Eloise was later retired.[37]

Season effects

This is a table of the storms in the 1975 Atlantic hurricane season. It mentions all of the season's storms and their names, landfall(s), peak intensities, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of such being a traffic accident or landslide), but are still related to that storm. The damage and death totals in this list include impacts when the storm was a precursor wave or post-tropical low, and all of the damage figures are in 1975 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | June 24–29 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | None | None | None | |||

| Amy | June 26 – July 4 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 981 | North Carolina, Newfoundland | Minimal | 1 | |||

| Three | July 4–5 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | Unknown | None | None | None | |||

| Blanche | July 23–28 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 980 | Maine, Nova Scotia | $6.2 million | None | |||

| Five | July 24–26 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1008 | Mexico | Unknown | None | |||

| Six | July 28–30 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida | >$8.5 million | 3 | |||

| Caroline | August 24 – September 1 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | 963 | Cuba, Yucatán Peninsula | Unknown | 2 | |||

| Doris | August 28 – September 4 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 965 | None | None | None | |||

| Eight | September 3–9 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | None | None | None | |||

| Nine | September 3–6 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | None | None | None | |||

| Ten | September 6–7 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | Unknown | Mexico | Unknown | None | |||

| Eleven | September 11–14 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | None | None | None | |||

| Eloise | September 13–24 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 955 | Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Florida, Alabama | >$550 million | 80 | |||

| Faye | September 18–29 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 977 | Bermuda | Minimal | None | |||

| Gladys | September 22 – October 3 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | 939 | None | None | None | |||

| Fifteen | September 25–30 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | Unknown | Yucatán Peninsula | Unknown | None | |||

| Sixteen | October 3–5 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | None | None | None | |||

| Seventeen | October 14–17 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida | Unknown | 1 | |||

| Hallie | October 24–28 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1002 | South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia | Minimal | None | |||

| Eighteen | October 27–29 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | Nicaragua, Honduras, Belize | Unknown | None | |||

| Nineteen | November 8–12 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | Honduras, Yucatán peninsula | Unknown | None | |||

| Twenty | November 29 – December 1 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | Unknown | None | None | None | |||

| Unnamed | December 6–13 | Subtropical storm | 70 (110) | 985 | None | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 23 systems | June 24 – December 13 | 140 (220) | 939 | >$564.7 million | 84 | |||||

See also

- 1975 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- 1975 Pacific hurricane season

- 1975 Pacific typhoon season

- Australian cyclone seasons: 1974–75, 1975–76

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 1974–75, 1975–76

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 1974–75, 1975–76

- South Atlantic tropical cyclone

- Mediterranean tropical-like cyclone

References

- Miles B. Lawrence (April 1979). Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1978 (PDF). Monthly Weather Review (Report). American Meteorological Society. p. 482. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- "Scientists Warn Coastal Areas of Hurricane Season". Zanesville Times Recorder. Miami, Florida. United Press International. June 1, 1975. p. 1. Retrieved February 24, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Philip J. Klotzbach and William M. Gray (December 8, 2006). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2007 (Report). Boulder, Colorado: Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 18 December 2006. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- "Boat survival 'tribute' to builder who died in coma". The Free-Lance-Star. Associated Press. July 17, 1975. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- 1975-Blanche (Report). Environment Canada. September 14, 2010. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 17 (7): 18. July 1975. ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- General Summary of National Flood Events. July 1975. p. 24. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Major Disaster Declared". The Palm Beach Post. Tallahassee, Florida. United Press International. August 23, 1975. p. 25. Retrieved March 17, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Rains create problems for Vietnam refugees". The Mercury. United Press International. August 1, 1975. p. 3. Retrieved April 12, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Paul J. Hebert (April 1976). Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1975 (PDF). Monthly Weather Review (Report). American Meteorological Society. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- Jay Barnes (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. Chapel Hill Press. pp. 239–242. ISBN 978-0-8078-3068-0.

- David M. Roth (November 23, 2008). Tropical Depression Twelve – October 15-20, 1975 (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. March 2014. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- Paul J. Hebert (April 1976). Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1975 (PDF). Monthly Weather Review (Report). American Meteorological Society. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- "Tropical Storm Amy Drifting Slowly At Sea". Ocala Star-Banner. Associated Press. June 30, 1975. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- Roth, David M (January 3, 2023). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Boat survival 'tribute' to builder who died in coma". The Free-Lance-Star. Associated Press. July 17, 1975. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- Canadian Tropical Cyclone Season Summary for 1975 (Report). Environment Canada. July 3, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- 1975-Blanche (Report). Environment Canada. September 14, 2010. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- David M. Roth (October 7, 2008). Tropical Depression Four – July 27–August 3, 1975. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 17 (7): 18. July 1975. ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- General Summary of National Flood Events. July 1975. p. 24. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Mid-Delta". Delta Democrat Times. August 3, 1975. p. 38. Retrieved April 9, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Major Disaster Declared". The Palm Beach Post. Tallahassee, Florida. United Press International. August 23, 1975. p. 25. Retrieved March 17, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Rains create problems for Vietnam refugees". The Mercury. United Press International. August 1, 1975. p. 3. Retrieved April 12, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Caroline Downgraded". The Daytona Beach News-Journal. Associated Press. September 1, 1975. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- Preliminary Report: Hurricane Caroline: August 24 – September 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. 1975. p. 2. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- "Texas Weather Last Year Seems 'Practically Normal'". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. March 2, 1976. p. 10B – via Newspapers.com.

- "Caroline is Downgraded, Mexico gets only light damage". The Galveston Daily News. United Press International. September 1, 1975.

- Jay Barnes (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. Chapel Hill Press. pp. 239–242. ISBN 978-0-8078-3068-0.

- "Hurricane Eloise Storm Kills 25 In Puerto Rico; Slams Dominican Republic". The Evening Independent. Associated Press. September 17, 1975. p. 2. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- John Pomfret. The History of Guantanamo Bay, Vol. II 1964 – 1982 (Report). Naval Station Guantanamo Bay.

- Rick Schwartz (2007). Hurricanes and the Middle Atlantic States. Blue Diamond Books. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-9786280-0-0.

- "Islands Feel Faye". The Ledger. Associated Press. September 27, 1975. Retrieved August 28, 2009.

- "Faye adds to flooding". St. Petersburg Times. United Press International. September 28, 1975. p. 1-A. Retrieved May 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1975-Gladys (Report). Moncton, New Brunswick: Environment Canada. November 4, 2009. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- David M. Roth (November 23, 2008). Tropical Depression Twelve – October 15-20, 1975 (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- Preliminary Report: Tropical Storm Hallie: October 24–28, 1975 (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- Preliminary Report: Tropical Storm Hallie: October 24–28, 1975 (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- David M. Roth (January 3, 2008). Tropical Storm Hallie – October 23–27, 1975. Weather Prediction Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- "Hallie Heads to Open Sea". The Ledger. Associated Press. October 27, 1975. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- "Tropical Depression Heads for Tampico, May Gain Strength". Los Angeles Times. September 8, 1975. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- "East coat hurricane target". The Post-Crescent. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. June 1, 1975. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2016. Retrieved February 18, 2017.