2009 Atlantic hurricane season

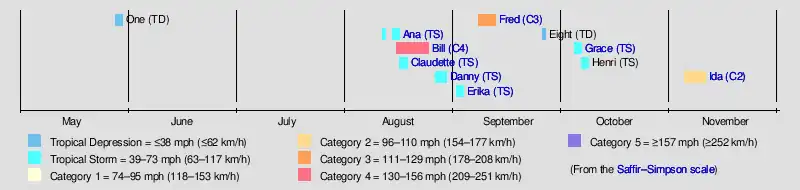

The 2009 Atlantic hurricane season was a below-average Atlantic hurricane season that produced eleven tropical cyclones, nine named storms, three hurricanes, and two major hurricanes.[1][nb 1] It officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30, dates that conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones develop in the Atlantic basin.[3] The season's first tropical cyclone, Tropical Depression One, developed on May 28,[4] while the final storm, Hurricane Ida, dissipated on November 10.[5] The most intense hurricane, Bill, was a powerful Cape Verde-type hurricane that affected areas from the Leeward Islands to Newfoundland.[6] The season featured the lowest number of tropical cyclones since the 1997 season, and only one system, Claudette, made landfall in the United States. Forming from the interaction of a tropical wave and an upper-level low, Claudette made landfall on the Florida Panhandle with maximum sustained winds of 45 mph (70 km/h) before quickly dissipating over Alabama. The storm killed two people and caused $228,000 (2009 USD) in damage.

| 2009 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 28, 2009 |

| Last system dissipated | November 10, 2009 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Bill |

| • Maximum winds | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 943 mbar (hPa; 27.85 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 11 |

| Total storms | 9 |

| Hurricanes | 3 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 9 direct |

| Total damage | ~ $57.99 million (2009 USD) |

| Related articles | |

Pre-season forecasts issued by Colorado State University (CSU) called for fourteen named storms and seven hurricanes, of which three were expected to attain major hurricane status.[nb 2] The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) later issued its initial forecast, which predicted nine to fourteen named storms, four to seven hurricanes, and one to three major hurricanes. After several revisions in the projected number of named storms, both agencies lowered their forecasts by the middle of the season.

Several storms made landfall or directly affected land outside of the United States. Tropical Storm Ana brought substantial rainfall totals to many of the Caribbean islands, including Puerto Rico, which led to minor street flooding. Hurricane Bill delivered gusty winds and rain to the island of Newfoundland, while Tropical Storm Danny affected the U.S. state of North Carolina, and Erika affected the Lesser Antilles as a poorly organized tropical system. Hurricane Fred affected the Cape Verde Islands as a developing tropical cyclone and Tropical Storm Grace briefly impacted the Azores, becoming the farthest northeast forming storm on record. The season's final storm, Ida, affected portions of Central America before bringing significant rainfall to the Southeast United States as an extratropical cyclone.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes | |

| Average (1950–2000) | 9.6 | 5.9 | 2.3 | ||

| Record high activity[7] | 30 | 15 | 7† | ||

| Record low activity[7] | 1 | 0 | 0† | ||

| CSU | December 10, 2008 | 14 | 7 | 3 | |

| CSU | April 7, 2009 | 12 | 6 | 2 | |

| NOAA | May 21, 2009 | 9–14 | 4–7 | 1–3 | |

| CSU | June 2, 2009 | 11 | 5 | 2 | |

| FSU COAPS | June 2, 2009 | 8 | 4 | N/A | |

| UKMO | June 18, 2009 | 6* | N/A | N/A | |

| CSU | August 4, 2009 | 10 | 4 | 2 | |

| NOAA | August 6, 2009 | 7–11 | 3–6 | 1–2 | |

| Actual activity | 9 | 3 | 2 | ||

| * July–November only. † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | |||||

Forecasts of hurricane activity are issued before each hurricane season by noted hurricane experts Philip J. Klotzbach, William M. Gray, and their associates at Colorado State University; and separately by NOAA forecasters.

Klotzbach's team (formerly led by Gray) defined the average number of storms per season (1950 to 2000) as 9.6 tropical storms, 5.9 hurricanes, 2.3 major hurricanes (storms reaching at least Category 3 strength in the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale) and an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) Index of 96.1.[8] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACE numbers. ACE is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm intensity.[9] NOAA defines a season as above-normal, near-normal or below-normal by a combination of the number of named storms, the number reaching hurricane strength, the number reaching major hurricane strength and ACE Index.[10]

Pre-season forecasts

On December 10, 2008, Klotzbach's team issued its first extended-range forecast for the 2009 season, predicting above-average activity (14 named storms, 7 hurricanes, 3 of Category 3 or higher and ACE Index of 125). On April 7, 2009, Klotzbach's team issued an updated forecast for the 2009 season, predicting near-average activity (12 named storms, 6 hurricanes, 2 of Category 3 or higher and ACE Index of 100), citing the possible cause as the high probability of a weak El Niño forming during the season.[11] On May 21, 2009, NOAA issued their forecast for the season, predicting near or slightly above average activity, (9 to 14 named storms, 4 to 7 hurricanes, and 1 to 3 of Category 3 or higher).[12]

Midseason outlooks

On June 2, 2009, Klotzbach's team issued another updated forecast for the 2009 season, predicting slightly below average activity (11 named storms, 5 hurricanes, 2 of Category 3 or higher and ACE Index of 85). Also on June 2, 2009, the Florida State University Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies (FSU COAPS) issued its first ever Atlantic hurricane season forecast. The FSU COAPS forecast predicted 8 named storms, including 4 hurricanes, and an ACE Index of 65.[13] On June 18, 2009, the UK Met Office (UKMO) issued a forecast of 6 tropical storms in the July to November period with a 70% chance that the number would be in the range 3 to 9. They also predicted an ACE Index of 60 with a 70% chance that the index would be in the range 40 to 80.[14] On August 4, 2009, Klotzbach's team updated their forecast for the 2009 season, again predicting slightly below average activity (10 named storms, 4 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes). On August 6, 2009, the NOAA also updated their forecast for the 2009 season, predicting below average activity (7–11 named storms, 3–6 hurricanes, and 1–2 major hurricanes).[15]

Seasonal summary

During the 2009 season, nine of the eleven tropical cyclones affected land, of which five actually made landfall. The United States experienced one of its quietest years, with no hurricanes making landfall in the country. Throughout the basin, six people were killed in tropical cyclone-related incidents and total losses reached roughly $77 million. Most of the damage resulted from Hurricane Bill, which caused severe beach erosion throughout the east coast of the United States. In the United States, tropical cyclones killed six people and caused roughly $46 million in damage. In the Lesser Antilles, Tropical Storms Ana and Erika brought moderate rainfall to several islands but resulted in little damage. Elsewhere in the Atlantic, the Azores Islands, Atlantic Canada, Bermuda, Cape Verde Islands and Wales were affected by tropical cyclones or their remnants.[1] In Canada, Hurricane Bill produced widespread moderate rainfall in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, leaving roughly $10 million in losses.[16] The hurricane also produced tropical storm-force winds in Bermuda.[6] Hurricane Fred briefly impacted the southern Cape Verde Islands as it bypassed the islands early in its existence.[17] The Azores and Wales were also affected by Tropical Storm Grace; however, both areas recorded only minor effects.[18]

The ACE index for the 2009 Atlantic hurricane season as calculated by Colorado State University using data from the National Hurricane Center was 52.6 units.[19] Due to the low number of storms in the season, many of which were short-lived, the overall ACE value was ranked as below-average.[20] Hurricane Bill was responsible for the ACE value for August being 30% above average.[21]

Systems

Tropical Depression One

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 28 – May 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1006 mbar (hPa) |

During late-May, a frontal boundary stalled near The Bahamas and slowly degenerated. On May 25, 2009, an area of low pressure developed along the tail-end of a decaying cold front near the northern Bahamas. Tracking northward, this low gradually developed as it moved within 85 mi (135 km) of North Carolina's Outer Banks. By May 28, deep convection developed across a small area over the low-pressure system, leading to the National Hurricane Center classifying the system as Tropical Depression One. It was the northernmost forming May tropical cyclone in Atlantic history, though subtropical cyclones formed equally far north in 1972 and 2007. It also marked the third consecutive year with pre-season tropical or subtropical cyclones in the basin. The depression moved over the warm waters of the Gulf Stream for the following 24 hours, allowing it to maintain its convection, before moving into a hostile environment characterized by strong wind shear and cooler waters. Late on May 29, the system degenerated into a remnant low. Several hours later, on May 30, about 345 mi (555 km) south-southeast of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Tropical Depression One was absorbed by a warm front.[4][22]

As a tropical cyclone, the depression had no impact on land. However, the precursor to the system brought scattered rainfall and increased winds to parts of the North Carolina coastline, but no damage.[4] Rainfall in Hatteras amounted to 0.1 in (2.5 mm) on May 27; sustained wind reached 15 mph (24 km/h) and gusts were measured up to 23 mph (37 km/h). The lowest sea level pressure recorded in relation to the system was 1009 mbar (hPa; 29.80 inHg).[23] Increased winds along coastal areas of the state was possible in relation to the outer edges of the depression.[24]

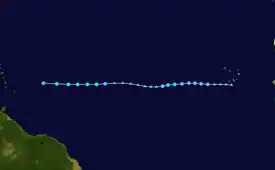

Tropical Storm Ana

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 11 – August 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

Ana formed out of an area of low pressure associated with a tropical wave on August 11, Ana briefly attained tropical storm intensity on August 12 before weakening back to a depression. The following day, the system degenerated into a non-convective remnant low as it tracked westward. On August 14, the depression regenerated roughly 1,075 mi (1,735 km) east of the Leeward Islands. Around 06:00UTC on August 15, the storm re-attained tropical storm status, at which time it was named Ana. After reaching a peak intensity with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 1003 mbar (hPa; 29.62 inHg), the storm began to weaken again due to increasing wind shear and the unusually fast movement of Ana. In post-storm analysis, it was discovered that Ana had degenerated into a tropical wave once more on August 16, before reaching any landmasses.[25]

Numerous tropical storm watches were issued for the Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic between August 15 and 17.[25] Several islands took minor precautions for the storm, including St. Croix which evacuated 40 residents from flood-prone areas ahead of the storm.[26] In the Dominican Republic, officials took preparations by setting up relief agencies and setting up shelters.[27] Impact from Ana was minimal, mainly consisting of light to moderate rainfall.[25] In Puerto Rico, up to 2.76 in (70 mm),[28] causing street flooding and forcing the evacuation of three schools. High winds associated with the storm also downed trees and power lines, leaving roughly 6,000 residents without power.[29]

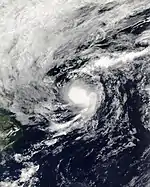

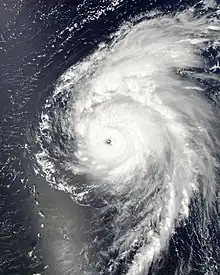

Hurricane Bill

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 15 – August 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); 943 mbar (hPa) |

As Ana regenerated into a tropical depression,[25] a new tropical depression developed early on August 15 southwest of the Cape Verde Islands. Light wind shear and warm waters allowed the depression to steadily intensify, becoming Tropical Storm Bill later that day. By August 17, Bill attained hurricane-status about midway between the Cape Verde Islands and the Lesser Antilles. Eventually the hurricane attained its peak intensity as a Category 4 storm roughly 345 mi (555 km) east-northeast of the Leeward Islands. The storm attained maximum winds of 130 mph (210 km/h), the highest of any storm during the season, before weakening slightly as it turned north. The large storm passed roughly 175 mi (280 km) west of Bermuda as a Category 2 hurricane. Further weakening took place as Bill brushed the southern coast of Nova Scotia the following day. Shortly before making landfall in Newfoundland, Bill weakened to a tropical storm and accelerated. The storm eventually transitioned into an extratropical cyclone after moving over the north Atlantic before being absorbed by a larger non-tropical low on August 24.[6]

Two people were killed by the storm's large swells—one in Maine and another in Florida. The hurricane came close enough to warrant tropical cyclone watches and warnings in both the US and Canada. Bill was one of three tropical storms active on August 16.[6] Large, life-threatening swells produced by the storm impacted north-facing coastlines of Puerto Rico and Hispaniola as Hurricane Bill approached Bermuda.[30] Along the coasts of North Carolina, waves averaging 10 ft (3.0 m) in height impacted beaches. On Long Island, beach damage was severe; in some areas the damage was worse than Hurricane Gloria in 1985.[31] In New York, severe beach erosion caused by the storm resulted in over $35.5 million in losses.[32]

Tropical Storm Claudette

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 16 – August 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

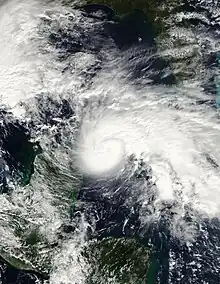

Just one day after the formation of Hurricane Bill, the season's third named storm developed on August 16. Forming out of a tropical wave and an upper-level low-pressure system, Claudette quickly intensified into a tropical storm offshore south of Tallahassee, Florida. By the afternoon, the storm had attained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and steadily tracked towards the Florida Panhandle. Early on August 17, the center of Claudette made landfall on Santa Rosa Island. Several hours after landfall, the storm weakened to a tropical depression and the Hydrometeorological Prediction Center took over primary responsibility of the storm. The system quickly dissipated and was last noted over Alabama on August 18.[33]

The National Hurricane Center issued tropical storm warnings for the Florida coastline and residents in some counties were advised to evacuate storm-surge-prone areas.[33][34] Tropical Storm Claudette, produced moderate rainfall across portions of Florida, Georgia, and Alabama between August 16 and 18. Two people were killed offshore amidst rough seas from the storm.[35] An EF-0 tornado spawned by the storm in Cape Coral damaged 11 homes, leaving $103,000 in damages. Additional damages to coastal property and beaches amounted to $125,000 as a result of Claudette.[36]

Tropical Storm Danny

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 26 – August 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1006 mbar (hPa) |

Around the same time the remnants of Hurricane Bill dissipated over the northern Atlantic,[6] a new tropical storm developed near the Bahamas on August 26. The system, immediately declared Tropical Storm Danny on its first advisory, erratically moved in a general northwestward direction. Danny attained peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) before succumbing to high wind shear. After turning northward, the storm weakened and was eventually absorbed by another low-pressure system off the east coast of the United States early on August 29.[37] High waves from Danny killed a boy in the Outer Banks.[38]

Tropical Storm Erika

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 1 – September 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

On September 1, the season's fifth named storm, Tropical Storm Erika, formed east of the Lesser Antilles. Upon forming, the storm had attained its peak intensity with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h). Persistent wind shear prevented the system from intensifying and resulted in the storm's convection being completely displaced from the center of circulation by the time it passed over Guadeloupe on September 2. After entering the Caribbean Sea, Erika briefly regained strength before fully succumbing to strong shear. The system eventually dissipated on September 4, to the south of Puerto Rico.[39] Damages were minor, though one island received several inches of rain.

Hurricane Fred

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 7 – September 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); 958 mbar (hPa) |

Several days after Erika dissipated,[39] a new tropical depression formed southeast of the Cape Verde Islands on September 7. This depression rapidly intensified within an environment of low wind shear and high sea surface temperatures. Receiving the name Fred on September 8, the storm quickly developed an eye feature and was upgraded to a hurricane roughly 24 hours after being named. Within a 12‑hour span, the storm's winds increased by 40 mph (65 km/h) to its peak of 120 mph (195 km/h). Upon reaching this intensity, Fred became the strongest storm on record south of 30°N and east of 35°W in the Atlantic basin. Not long after the intensification ceased, it began to weaken as dry air became entrained within the system. By September 11, the storm nearly stalled northwest of the Cape Verde Islands and weakened to a tropical storm. The following day, Fred degenerated into a remnant low before taking a westward track across the Atlantic. The remnants of Fred persisted for nearly a week, nearly regenerating into a tropical depression several times. The low eventually dissipated on September 19, to the south of Bermuda.[17]

Tropical Depression Eight

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 25 – September 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1008 mbar (hPa) |

In late September, a new, well-defined tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa into the Atlantic Ocean. By September 25, the system had developed sufficient deep convection for the NHC to classify it as Tropical Depression Eight. At this time, the depression attained its peak intensity with winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1008 mbar (hPa). Shortly thereafter, wind shear and decreasing sea surface temperatures caused the depression to weaken. The system degenerated into a remnant low on September 26 before degenerating into a trough of low pressure.[40]

Tropical Storm Grace

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 4 – October 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 986 mbar (hPa) |

Originating from an extratropical cyclone east of Newfoundland on September 27, the precursor to Tropical Storm Grace tracked southeastward towards the Azores, gaining subtropical characteristics. After executing a counterclockwise loop between October 1 and 3, deep convection wrapped around a small circulation center that had developed within the larger cyclone. On October 4, this smaller low developed into a tropical storm while situated near the Azores Islands, becoming the northeasternmost forming Atlantic tropical cyclone on record. The storm quickly turned northeastward and intensified, developing an eye-like feature as it attained peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 986 mbar (hPa; 29.12 inHg). It weakened over increasingly colder waters and began merging with an approaching frontal boundary. Early on October 6, Grace transitioned into an extratropical cyclone before dissipating later that day near Wales.[18]

Although Grace passed through the Azores Islands, the storm had little known effects there.[18] In Europe, the system and its remnants brought rain to several countries, including Portugal,[41] the United Kingdom[42] and Belgium.[43] No fatalities were linked to Grace and overall damage was minimal.[18]

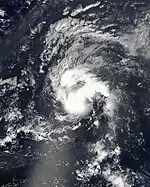

Tropical Storm Henri

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 6 – October 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave left the coast of Africa on October 1, moving westward with intermittent showers and thunderstorms.[44] On October 5, the system became better organized,[45] and a low-pressure area formed.[46] Although the thunderstorms were displaced east of the center of circulation and the probability for development was never high, the disturbance became a tropical depression around 0000 UTC on October 6 about 775 mi (1,245 km) east of the Lesser Antilles.[44] Operationally, the storm was not designated a tropical cyclone until later on October 6, when it was immediately declared a tropical storm.[47]

Affected by strong wind shear, Henri remained disorganized with its center located on the western edge of the convection. Moving northwestward, Henri intensified slightly to peak winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) on October 7 after the convection increased. Shortly thereafter, the wind shear grew stronger, and on October 8 the storm weakened to a tropical depression.[44] The structure became further disorganized with several low-level vortices.[48] Just twelve hours after weakening into a depression, Henri degenerated into a remnant area of low pressure. The remnants continued northwestward before turning to the west-southwest due to a ridge. On October 11, the storm's circulation dissipated near Hispaniola, having never impacted land.[44]

Hurricane Ida

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 4 – November 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 975 mbar (hPa) |

The final storm of the 2009 season formed over the southern Caribbean Sea on November 4. The slow moving system quickly developed into Tropical Storm Ida within a favorable environment as it neared the coastline of Nicaragua. Several hours before moving over land, Ida attained hurricane-status, with winds reaching 80 mph (130 km/h). Hours after moving inland, Ida weakened to a tropical storm and further to a tropical depression as it turned northward. On November 7, the depression re-entered the Caribbean Sea and quickly intensified. Early on November 8, the system re-attained hurricane intensity as it rapidly intensified over warm waters. Ida attained its peak intensity as a Category 2 hurricane early the next day with winds of 105 mph (170 km/h) as it moved over the Yucatán Channel. Not long after reaching this intensity, Ida quickly weakened to a tropical storm as it entered the Gulf of Mexico. Despite strong wind shear, the storm briefly re-attained hurricane status for a third time near the southeastern Louisiana coastline before quickly weakening to a tropical storm. Shortly before moving inland over the southern United States, Ida transitioned into an extratropical cyclone. The remnants of Ida persisted until November 11, at which time the low dissipated. Remnant energy from Ida provided energy for another system which became a powerful nor'easter, causing significant damage in the Mid-Atlantic States. The resulting storm came to be known as Nor'Ida.[5]

In the southern Caribbean, Hurricane Ida caused roughly $2.1 million in damage in Nicaragua after destroying numerous homes and leaving an estimated 40,000 people homeless.[49][50] Ida also produced significant rainfall across portions of western Cuba, with some areas recording up to 12.5 in (320 mm) of rain during the storm's passage.[5] In the United States, the hurricane and the subsequent nor'easter caused substantial damage, mainly in the Mid-Atlantic States.[5] One person was killed by Ida after drowning in rough seas while six others were killed in various incidents related to the nor'easter. Overall, the two systems caused nearly $300 million in damage throughout the country.[36]

Storm names

The following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the North Atlantic in 2009. This was the same list used in the 2003 season, with the exceptions of Fred, Ida, and Joaquin, which replaced Fabian, Isabel, and Juan, respectively. The names Fred and Ida were used for the first time this year. There were no names retired this year; thus, the same list was used again in the 2015 season.[51]

|

|

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that formed in the 2009 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, intensities, areas affected, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 2009 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | May 28–29 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1006 | North Carolina | None | None | |||

| Ana | August 11–16 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1003 | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Cuba, The Bahamas | Minimal | None | |||

| Bill | August 15–24 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | 943 | Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, United States East Coast, Bermuda, Atlantic Canada, British Isles | $46.2 million | 2 | |||

| Claudette | August 16–18 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1005 | Southeastern United States | $350,000 | 2 | |||

| Danny | August 26–29 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1006 | North Carolina, Northeastern United States, Atlantic Canada | Minimal | 1 | |||

| Erika | September 1–3 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1004 | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic | $35,000 | None | |||

| Fred | September 7–12 | Category 3 hurricane | 120 (195) | 958 | Cape Verde | None | None | |||

| Eight | September 25–26 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1008 | None | None | None | |||

| Grace | October 4–6 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 986 | Azores, Portugal, British Isles | Minimal | None | |||

| Henri | October 6–8 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1005 | Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles | None | None | |||

| Ida | November 4–10 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 975 | Central America, Cayman Islands, Yucatán Peninsula, Cuba, Southeastern United States | $11.4 million | 4 | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 11 systems | May 28 – November 10 | 130 (215) | 943 | ~$57.99 million | 9 | |||||

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 2009

- 2009 Pacific hurricane season

- 2009 Pacific typhoon season

- 2009 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2008–09, 2009–10

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2008–09, 2009–10

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2008–09, 2009–10

- South Atlantic tropical cyclone

- Mediterranean tropical-like cyclone

References

- National Hurricane Center (November 30, 2009). "Slow Atlantic Hurricane Season Comes to a Close". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 1 February 2010. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 4, 2011. Archived from the original on 2010-08-26. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- Neal Dorst (2009). "Subject: G1) When is hurricane season?". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 16, 2008. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- Robbie Berg (June 12, 2009). "Tropical Depression One Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- Lixion A. Avila and John Cangialosi (January 14, 2010). "Hurricane Ida Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- Lixion A. Avila (January 18, 2010). "Hurricane Bill Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- "North Atlantic Ocean Historical Tropical Cyclone Statistics". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- Philip J. Klotzbach and William M. Gray (2008-12-10). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2009" (PDF). Colorado State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 15, 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. September 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- National Hurricane Center (May 22, 2008). "NOAA Atlantic Hurricane Season Classifications". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 15, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- William M. Gray (April 7, 2009). "Mid-Season Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2009" (PDF). Colorado State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 April 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- Michael E. Ruane (May 21, 2009). "Government Weather Officials Predict Average 2009 Season". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies. "FSU COAPS Atlantic Hurricane Season Forecast Archive". Florida State University. Archived from the original on 19 June 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- "Appraisal of the 2009 Met Office seasonal tropical storm forecast for the North Atlantic" (PDF). United Kingdom Meteorological Office. 2009. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- National Hurricane Center (August 6, 2009). "NOAA Lowers Hurricane Season Outlook, Cautions Public Not to Let Down Guard". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 1 February 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- Glenn McGillivary (January 2010). "Annus Horriblis, The Sequel" (PDF). Institute for Catastrophe Loss Reduction. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- Michael J. Brennan (October 23, 2009). "Hurricane Fred Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- Robbie Berg (November 28, 2009). "Tropical Storm Grace Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- "Basin Archives: North Atlantic Ocean Historical Tropical Cyclone Statistics". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- National Weather Service (2008). "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2010-08-26. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- Hurricane Specialists Unit (September 1, 2009). "August 2009 Tropical Weather Summary". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- National Hurricane Center (2009). "Easy-to-Read-HURDAT 1851–2008". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- "History for Hatteras, NC: May 27, 2009 Weather". Weather Underground. May 27, 2008. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Rob Nucatola (May 28, 2009). "Tropical Depression One Forms". WCTV. Archived from the original on August 31, 2015. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- Eric S. Blake (September 26, 2009). "Tropical Storm Ana Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- Staff Writer (August 18, 2009). "República Dominicana respira ante degradación de "Ana" en onda tropical" (in Spanish). Cope. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- Staff Writer (August 17, 2009). "Activan organismos por depresión tropical Ana" (in Spanish). Dominicanos Hoy. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- David M. Roth (2009). "Tropical Storm Ana – August 17–18, 2009". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- Gerardo E. (August 18, 2009). "Ana se deja sentir en la Isla" (in Spanish). El Nuevo Dia. Archived from the original on April 20, 2010. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- "Bermuda placed on alert as Hurricane Bill advances". Taiwan News. Agence France-Presse. August 22, 2009. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Shelby Sebens (August 22, 2009). "No deaths or major damage as hurricane Bill passes". Star News. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- Russell Drumm (December 3, 2009). "Federal, State Funds Sought for Damage". The East Hampton Star. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- Richard J. Pasch (January 5, 2010). "Tropical Storm Claudette Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- Staff Writer (August 16, 2009). "Severe Weather — Gulf County". WMBB13. Archived from the original on August 17, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- Stuart Hinson (2009). "Florida Event Report: Storm Surge/Tide". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2012-08-05. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- "NCDC Storm Events Database". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Archived from the original on 10 April 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- John L. Beven II (January 6, 2010). "Tropical Storm Danny Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- "Body of boy missing off Outer Banks recovered". WRAL. September 1, 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-09-04. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- Daniel P. Brown (October 29, 2009). "Tropical Storm Erika Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- Todd B. Kimberlain (October 23, 2009). "Tropical Depression Eight Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- André Ferreira (October 7, 2009). "'Grace' traz vento e chuva até sexta" (in Portuguese). Cofina Media. Archived from the original on September 7, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- Tiffany Curnick (October 8, 2009). "Grace Not Typically Tropical, But Parma The Real Deal". Press Association Mediapoint.

- "Flash du 8 octobre 2009 : Pluies orageuses" (in French). Météo Belgique. October 8, 2009. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- Eric Blake (November 17, 2009). "Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Henri" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- Michael Brennan (October 5, 2009). "Tropical Weather Outlook for October 5, 2009". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- Daniel Brown and David Roberts (October 5, 2009). "Tropical Weather Outlook for October 5, 2009". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- Robbie Berg (October 6, 2009). "Tropical Storm Henri Discussion Number 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- Eric Blake (October 8, 2009). "Tropical Depression Henri Discussion Number 8". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- Staff Writer (November 6, 2009). "El huracán 'Ida' deja al menos 40.000 damnificados en Nicaragua" (in Spanish). Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- Sergio León (November 5, 2009). "Huracán deja estela de daños en la RAAS". La Prensa (in Spanish). Archived from the original on December 26, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- National Hurricane Center (April 17, 2015). "Retired Hurricane Names Since 1954". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

Notes

- An average season, as defined by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has twelve tropical storms, six hurricanes and two major hurricanes.[2]

- A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale.

External links

- Satellite loop of the 2009 Atlantic hurricane season

- HPC rainfall page for 2009 Tropical Cyclones

- National Hurricane Center Website

- National Hurricane Center's Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook

- Tropical Cyclone Formation Probability Guidance Product