2002 Atlantic hurricane season

The 2002 Atlantic hurricane season was a near-average Atlantic hurricane season. It officially started on June 1, 2002, and ended on November 30, dates which conventionally limit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones develop in the Atlantic Ocean. The season produced fourteen tropical cyclones, of which twelve developed into named storms; four became hurricanes, and two attained major hurricane status. While the season's first cyclone did not develop until July 14, activity quickly picked up: eight storms developed in the month of September. It ended early however, with no tropical storms forming after October 6—a rare occurrence caused partly by El Niño conditions. The most intense hurricane of the season was Hurricane Isidore with a minimum central pressure of 934 mbar, although Hurricane Lili attained higher winds and peaked at Category 4 whereas Isidore only reached Category 3. However, Lili had a minimum central pressure of 938 mbar.

| 2002 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | July 14, 2002 |

| Last system dissipated | October 16, 2002 |

| Strongest storm | |

| By maximum sustained winds | Lili |

| • Maximum winds | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 938 mbar (hPa; 27.7 inHg) |

| By central pressure | Isidore |

| • Maximum winds | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 934 mbar (hPa; 27.58 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 14 |

| Total storms | 12 |

| Hurricanes | 4 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 50 total |

| Total damage | $2.47 billion (2002 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The season was less destructive than normal, causing an estimated $2.47 billion (2002 USD) in property damage and 50 fatalities. Most destruction was due to Isidore, which caused about $1.28 billion (2002 USD) in damage and killed seven people in the Yucatán Peninsula and later the United States, and Hurricane Lili, which caused $1.16 billion (2002 USD) in damage and 15 deaths as it crossed the Caribbean Sea and eventually made landfall in Louisiana.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes | |

| CSU | Average (1950–2000)[1] | 9.6 | 5.9 | 2.3 | |

| NOAA | Average (1950–2005)[2] | 11.0 | 6.2 | 2.7 | |

| Record high activity[3] | 30 | 15 | 7 | ||

| Record low activity[3] | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| CSU | December 7, 2001[1] | 13 | 8 | 4 | |

| CSU | April 5, 2002[4] | 12 | 7 | 3 | |

| NOAA | May 20, 2002[5] | 9–13 | 6–8 | 2–3 | |

| CSU | August 7, 2002[6] | 9 | 4 | 1 | |

| NOAA | August 8, 2002[7] | 7–10 | 4–6 | 1–3 | |

| CSU | September 3, 2002[8] | 8 | 3 | 1 | |

| Actual activity | 12 | 4 | 2 | ||

Noted hurricane expert William M. Gray and his associates at Colorado State University issue forecasts of hurricane activity each year, separately from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Gray's team determined the average number of storms per season between 1950 and 2000 to be 9.6 tropical storms, 5.9 hurricanes, and 2.3 major hurricanes (storms exceeding Category 3). A normal season, as defined by NOAA, has 9 to 12 named storms, of which 5 to 7 reach hurricane strength and 1 to 3 become major hurricanes.[1][2]

Pre-season forecasts

On December 7, 2001, Gray's team issued its first extended-range forecast for the 2002 season, predicting above-average activity (13 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and about 2 of Category 3 or higher). It listed an 86 percent chance of at least one major hurricane striking the U.S. mainland. This included a 58 percent chance of at least one major hurricane strike on the East Coast, including the Florida peninsula, and a 43 percent chance of at least one such strike on the Gulf Coast from the Florida Panhandle westward. The potential for major hurricane activity in the Caribbean was forecast to be above average.[1]

On April 5 a new forecast was issued, calling for 12 named storms, 7 hurricanes and 3 intense hurricanes. The decrease in the forecast was attributed to the further intensification of El Niño conditions. The estimated potential for at least one major hurricane to affect the U.S. was decreased to 75 percent; the East Coast potential decreased slightly to 57 percent, and from the Florida Panhandle westward to Brownsville, Texas, the probability remained the same.[4]

Mid-season forecasts

On August 7, 2002, Gray's team lowered its season estimate to 9 named storms, with 4 becoming hurricanes and 1 becoming a major hurricane, noting that conditions had become less favorable for storms than they had been earlier in the year. The sea-level pressure and trade wind strength in the tropical Atlantic were reported to be above normal, while sea surface temperature anomalies were on a decreasing trend.[6]

On August 8, 2002, NOAA revised its season estimate to 7–10 named storms, with 4–6 becoming hurricanes and 1–3 becoming major hurricanes. The reduction was attributed to less favorable environmental conditions and building El Niño conditions.[7]

Seasonal summary

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1, 2002.[9] It was a near-average season in which 14 tropical cyclones formed. Twelve depressions attained tropical storm status, and four of these reached hurricane status. Two hurricanes further intensified into major hurricanes.[10] Activity was suppressed somewhat by an El Niño, which was of near-moderate intensity by August.[7] Four named storms made landfall in Louisiana, a record which was later tied in 2020.[11] Overall, the Atlantic tropical cyclones of 2002 collectively resulted in 50 deaths and around $2.47 billion in damage.[12] The season ended on November 30, 2002.[9]

Tropical cyclogenesis began with Tropical Storm Arthur, which formed just offshore North Carolina on July 14. Following the storm's extratropical transition on July 16, no further activity occurred until Tropical Storm Bertha developed near Louisiana on August 4. Cristobal formed on the next day, while Dolly developed on August 29.[10] September featured eight named storms, a record which was later tied in 2007 and 2010 and surpassed in 2020.[13] During that month, Gustav reached hurricane intensity on September 11, the latest date of the first hurricane in a season since 1941.[14] While the long-lasting Kyle and Lili persisted into October, only one tropical cyclone developed that month, Tropical Depression Fourteen on October 14. The depression was absorbed by a cold front while crossing Cuba two days later, ending seasonal activity.[10]

The season's activity was reflected with a low accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 67, the lowest total since 1997. ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm status.[15]

Systems

Tropical Storm Arthur

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 14 – July 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 997 mbar (hPa) |

Arthur formed out of a tropical depression off the coast of North Carolina on July 14 from a decaying frontal zone. It then moved out to sea, strengthening slightly into a tropical storm on July 15. Arthur gradually strengthened and peaked as a 60 mph (97 km/h) tropical storm on the following day. However, cooler waters and upper-level shear caused it to weaken. By July 17, Arthur had become extratropical, and moved north over Newfoundland. It proceeded to weaken below gale strength.[16] The precursor system produced up to 4.49 in (114 mm) of rainfall in Weston, Florida.[17] Later, one person drowned in the Conne River in Newfoundland due to Arthur.[18]

Tropical Storm Bertha

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 4 – August 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A surface trough of low pressure that would later spawn Tropical Storm Cristobal developed a tropical depression in the northern Gulf of Mexico on August 4. It quickly strengthened into a minimal tropical storm early on August 5, and made landfall near Boothville, Louisiana, just two hours later. Bertha weakened to a tropical depression, but retained its circulation over Louisiana. A high-pressure system built southward, unexpectedly forcing the depression to the southwest. It emerged back over the Gulf of Mexico on August 7, where proximity to land and dry air prevented further strengthening. Bertha moved westward and made a second landfall near Kingsville, Texas, on August 9 with winds of only 25 mph (40 km/h). The storm dissipated about 10 hours later.[19]

Across the Gulf Coast of the United States, Bertha dropped light to moderate rainfall; most areas received less than 3 inches (76 mm). Precipitation from the storm peaked at 10.25 inches (260 mm) in Norwood, Louisiana. Minor flooding was reported, which caused light damage to a few businesses, 15 to 25 houses, and some roadways. Overall, damage was very minor, totaling to $200,000 (2002 USD) in damage.[20] In addition, one death was reported due to Bertha, a drowning due to heavy surf in Florida.[19]

Tropical Storm Cristobal

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 5 – August 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 999 mbar (hPa) |

On August 5, Tropical Depression Three formed off the coast of South Carolina from a surface trough of low pressure – the same trough that spawned Tropical Storm Bertha in the Gulf of Mexico. Under a southerly flow, the depression drifted southward, where dry air and wind shear inhibited significant development. On August 7, it became Tropical Storm Cristobal, and reached a peak of 50 mph (80 km/h) on August 8. The storm meandered eastward and was absorbed by a front on August 9.[21]

The interaction between the extratropical remnant and a high-pressure system produced strong rip currents along the coastline of Long Island. The storm also caused waves of three to four ft (1.2 m) in height. Three people drowned from the rip currents and waves in New York.[22]

Tropical Storm Dolly

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 29 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 997 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave exited the African coast on August 27,[23] and with low favorable conditions the system organized into Tropical Depression Four on August 29 about 630 mi (1,010 km) southwest of Cape Verde.[24] Six hours later, the depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Dolly after developing sufficient outflow and curved banding features.[25] The storm continued to intensify as more convection developed,[26] and Dolly reached peaked winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) on August 30.[23] After peaking in intensity, the storm suddenly lost organization,[27] and the winds decreased to minimal tropical storm force.[28] After a brief re-intensification trend, Dolly again weakened due to wind shear. On September 4, Dolly weakened to a tropical depression, and later that day was absorbed by the trough; it never affected land.[23]

Tropical Storm Edouard

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 1 – September 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 1002 mbar (hPa) |

Edouard formed out of an area of disturbed weather north of the Bahamas on September 2. It drifted northward, then executed a clockwise loop off the coast of Florida. Despite dry air and moderate upper-level shear, Edouard strengthened to a peak of 65 mph (105 km/h) winds, but the unfavorable conditions caught up with it. The storm weakened as it turned west-southwestward, and made landfall near Ormond Beach, Florida on September 5 as a minimal tropical storm. Edouard crossed Florida, and emerged over the Gulf of Mexico as a minimal depression. Outflow from the stronger Tropical Storm Fay caused Tropical Depression Edouard to weaken further, and Edouard was eventually absorbed by Fay.[29]

Tropical Storm Edouard dropped moderate rainfall across Florida, peaking at 7.64 inches (194 mm) in DeSoto County.[30] Though it was a tropical storm at landfall, winds were light across the path of the storm over land. Several roads were flooded from moderate precipitation. No casualties were reported, and damage was minimal.[29]

Tropical Storm Fay

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 5 – September 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 998 mbar (hPa) |

In early September, a low pressure center developed along a trough of low pressure, and on September 5, the system had gained sufficient organization to be a tropical depression, to the southeast of Galveston. The depression drifted south-southwest while strengthening into Tropical Storm Fay, reaching its peak strength of 60 mph (97 km/h) on the morning of September 6. The system then abruptly turned to the west-northwest, and remained steady in strength and course until landfall the next day, near Matagorda. It quickly degenerated into a remnant low, which itself moved slowly southwestward over Texas. The low eventually dissipated on September 11 over northeastern Mexico.[31]

The storm brought heavy rainfall in Mexico and Texas. The storm also caused six tornadoes, up to 20 in (510 mm) of rain, and extended periods of tropical storm force winds.[31] The storm caused moderate flooding in some areas due to high rainfall amounts, which left about 400 homes with some form of damage. In total, 400 houses sustained damage from flooding.[32] 1,575 houses were damaged from the flooding or tornadic damage, 23 severely, amounting to $4.5 million (2002 USD) in damage. No deaths are attributed to Fay.[33]

Tropical Depression Seven

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 7 – September 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1013 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave exited Africa on September 1, and after initial development became disorganized. It moved west-northwestward for a week, reorganizing enough by September 7 to be declared Tropical Depression Seven about 1,155 mi (1,859 km) east-southeast of Bermuda.[34] At the time, the depression had persistent convection around a small circulation, and it moved steadily westward due to a ridge to its north.[35] Shortly after forming, strong wind shear diminished the convection and left the center partially exposed.[36] By September 8, there was no remaining thunderstorm activity,[37] and the depression degenerated into a remnant low-pressure area.[38] The storm dissipated shortly after as strong wind shear continued to cause the storm to deteriorate while located 980 mi (1580 mi) southeast of Bermuda. The depression never affected land.[34]

Hurricane Gustav

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 8 – September 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 960 mbar (hPa) |

An area of unsettled weather developed between the Bahamas and Bermuda on September 6, and over the next few days convection increased in intensity and coverage. On September 8, the system gained sufficient organization to be declared a subtropical depression off the Southeast United States coast; later that day, the system was named Subtropical Storm Gustav. After attaining tropical characteristics on September 10, Gustav passed slightly to the east of the Outer Banks of North Carolina as a tropical storm before. While moving northeastward, Gustav intensified into a hurricane on September 11 and briefly became a Category 2 hurricane, prior to making two landfalls in Atlantic Canada as a Category 1 hurricane on September 12. Gustav became extratropical over Newfoundland around 1200 UTC that day, though the remnants meandered over the Labrador Sea before dissipating on September 15.[39][40]

The storm was responsible for one death and $100,000 (2002 USD) in damage, mostly in North Carolina. The interaction between Gustav and a non-tropical system produced strong winds that caused an additional $240,000 (2002 USD) in damage in New England, but this damage was not directly attributed to the hurricane. In Atlantic Canada, the hurricane and its remnants brought heavy rain, tropical storm and hurricane-force winds, as well as storm surges for several days.[39] Localized flooding was reported in areas of Prince Edward Island, and 4,000 people in Halifax, Nova Scotia and Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island were left without power.[41]

Tropical Storm Hanna

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 12 – September 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1001 mbar (hPa) |

In early September, a tropical wave merged with a trough of low pressure in the Gulf of Mexico and spawned a low-pressure system. Convection steadily deepened on September 11 east of the upper-level low and the surface low; it was classified as Tropical Depression Nine the next day. The disorganized storm moved westward, then northward, where it strengthened into Tropical Storm Hanna later that day. After reaching a peak with winds of 60 mph (97 km/h), it made two landfalls on the Gulf Coast, eventually dissipating on September 15 over Georgia.[42]

Because most of the associated convective activity was east of the center of circulation, minimal damage was reported in Louisiana and Mississippi.[42] To the east on Dauphin Island, Alabama, the storm caused coastal flooding which closed roads and forced the evacuation of residents. Portions of Florida received high wind gusts, heavy rainfall, and strong surf that resulted in the deaths of three swimmers.[43] Throughout the state, 20,000 homes lost electricity.[44] The heavy rainfall progressed into Georgia, where significant flooding occurred. Crop damage was extensive, and over 300 structures were damaged by the flooding. Overall, Hanna caused a total of about $20 million (2002 USD) in damage and three fatalities.[42]

Hurricane Isidore

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 14 – September 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min); 934 mbar (hPa) |

On September 9, a tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa, and by September 14 it was classified as a tropical depression. The next day the storm was located just south of Jamaica, and it developed into Tropical Storm Isidore. On September 19, it intensified into a hurricane, and Isidore made landfall in western Cuba as a Category 1 storm. Just before landfall near Puerto Telchac on September 22, Isidore reached its peak intensity, with wind speeds of 125 mph (201 km/h), making it a strong Category 3 storm. After returning to the Gulf of Mexico as a tropical storm, Isidore's final landfall was near Grand Isle, Louisiana, on September 26. The storm weakened to a tropical depression over Mississippi early the following day, before becoming extratropical over Pennsylvania later on September 27 and then being absorbed by a frontal system.[45]

Isidore made landfall on the Yucatán Peninsula of southern Mexico as a Category 3 hurricane, leaving $950 million (2002 USD) in damage in the country.[46] Despite dropping over 30 inches (760 mm) of rainfall among other effects,[47] only two indirect deaths were reported there.[48] As a tropical storm, Isidore produced a maximum of 15.97 inches (406 mm) of rainfall in the United States at Metairie, Louisiana.[47] The rainfall was responsible for flooding that caused moderate crop damage, with a total of $330 million in damage (2002 USD).[49]

Tropical Storm Josephine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 17 – September 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1009 mbar (hPa) |

A non-tropical low developed along a dissipating stationary front on September 16 in the central Atlantic and drifted north-northeastward.[50] The National Hurricane Center classified it as Tropical Depression Eleven on September 17 about 710 mi (1,140 km) east of Bermuda, and initially the depression did not have significant deep convection.[51] A wind report early on September 18 indicated the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Josephine. The storm continued generally northeastward, steered between a subtropical high to the northeast and a frontal system approaching from the west.[52] Josephine maintained a well-defined circulation, but its deep convection remained intermittent.[53] Early on September 19 the storm began being absorbed by the cold front, and as a tropical cyclone its winds never surpassed 40 mph (64 km/h).[54] Later that day Josephine transitioned into an extratropical cyclone and suddenly intensified to winds of 60 mph (97 km/h). The extratropical low was quickly absorbed by another larger extratropical system on the afternoon of September 19.[50][55]

Hurricane Kyle

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 20 – October 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 980 mbar (hPa) |

A non-tropical low formed into Subtropical Depression Twelve, well east-southeast of Bermuda on September 20. It became Subtropical Storm Kyle the next day, and Tropical Storm Kyle on September 22. Kyle drifted slowly westward, slowly strengthening, and reached hurricane strength on September 25; it weakened back into a tropical storm on September 28. The cyclone's strength continued to fluctuate between tropical depression and tropical storm several times. Its movement was also extremely irregular, as it shifted sharply north and south along its generally westward path. On October 11, Kyle reached land and made its first landfall near McClellanville, South Carolina. While skirting the coastline of the Carolinas, it moved back over water, and made a second landfall near Long Beach, North Carolina later the same day. Kyle continued out to sea where it merged with a cold front on October 12, becoming the fourth longest-lived Atlantic hurricane.[56]

Kyle brought light precipitation to Bermuda, but no significant damage was reported there.[57] Moderate rainfall accompanied its two landfalls in the United States,[58] causing localized flash flooding and road closures. Floodwaters forced the evacuation of a nursing home and several mobile homes in South Carolina. Kyle spawned at least four tornadoes,[56] the costliest of which struck Georgetown, South Carolina; it damaged 106 buildings and destroyed seven others, causing eight injuries.[59] Overall damage totaled about $5 million (2002 USD), and no direct deaths were reported.[56] However, the remnants of Kyle contributed to one indirect death in the British Isles.[60]

Hurricane Lili

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 21 – October 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min); 938 mbar (hPa) |

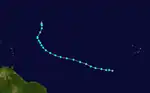

On September 16, a tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa and across the Atlantic. It developed a low level cloud circulation midway between Africa and the Lesser Antilles on September 20. The next day, the system had become sufficiently organized to classify the system as a tropical depression about 1,035 miles (1,665 km) east of the Windward Islands and intensified into Tropical Storm Lili on September 23. After nearly reaching hurricane status over the eastern Caribbean, the storm degenerated into a tropical wave on September 25, before becoming a tropical depression again early on September 27. The cyclone re-intensified into a tropical storm several hours later. On September 30, Lili became a hurricane while passing over the Cayman Islands. After striking Cuba's Isla de la Juventud and Pinar del Río Province as a Category 2, the storm attained Category 4 status in the Gulf of Mexico, However, Lili rapidly weakened to a Category 1 hurricane before making landfall near Intracoastal City, Louisiana, on October 3. The next day, it was absorbed by an extratropical low near the Tennessee – Arkansas border.[61]

In Louisiana, wind gusts reaching 120 mph (190 km/h), coupled with over 6 inches (150 mm) of rainfall and a storm surge of 12 feet (3.7 m), caused $1.1 billion (2002 USD) in damage. A total of 237,000 people lost power, and oil rigs offshore were shut down for up to a week.[62]

Tropical Depression Fourteen

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 14 – October 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1002 mbar (hPa) |

A weak tropical wave moved through the Lesser Antilles on October 9. As the system reached the southwestern Caribbean Sea on October 12, convection increased, and a broad low-pressure area formed later that day. Over the next two days, the low significantly organized, and became Tropical Depression Fourteen at 1200 UTC on October 14. The depression initially tracked west-northwestward, but then curved to the north-northeast. Due to vertical wind shear, the depression was unable to intensify, and remained below tropical storm status during its duration. By 1600 UTC on October 16, the depression made landfall near Cienfuegos, Cuba with winds of 30 mph (48 km/h). While crossing the island, the depression was absorbed by a cold front early on October 17. Minimal impact was reported, which was limited to locally heavy rains over portions of Jamaica, Cuba, and the Cayman Islands.[63]

Storm names

The following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the North Atlantic in 2002.[64] The names not retired from this list were used again in the 2008 season. This was the same list used in the 1996 season, with the exception of the names Cristobal, Fay and Hanna, which replaced Cesar, Fran and Hortense respectively. The three new names were used for Atlantic storms for the first time.[65]

|

Beginning in 2002, subtropical cyclones were named from the standard predetermined naming list upon gaining gale-force winds. This was first demonstrated with Gustav, which originated as a subtropical cyclone and was named from the predetermined list before becoming tropical and intensifying into a hurricane.

Retirement

On March 30, 2003, the World Meteorological Organization retired the names Isidore and Lili from its rotating Atlantic hurricane name lists due to the damage each caused. Those names were replaced with Ike and Laura for the 2008 season.[65]

Season effects

The following table lists all of the storms that formed in the 2002 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, intensities, areas affected, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 2002 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthur | July 14–16 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 997 | Southeastern United States | Minimal | 1 | |||

| Bertha | August 4–9 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1007 | Mississippi | $200,000 | 1 | |||

| Cristobal | August 5–8 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 999 | Bermuda, New York | Minimal | 0 (3) | |||

| Dolly | August 29 – September 4 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 997 | None | None | None | |||

| Edouard | September 1–6 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 1002 | Florida | Minimal | None | |||

| Fay | September 5–8 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 998 | Texas, Northern Mexico | $4.5 million | None | |||

| Seven | September 7–8 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1013 | None | None | None | |||

| Gustav | September 8–12 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 960 | North Carolina, Virginia, New Jersey, New England | $340,000 | 1 (3) | |||

| Hanna | September 12–15 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1001 | Florida, Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, Southeastern U.S., Mid Atlantic | $20 million | 3 | |||

| Isidore | September 14–27 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 934 | Venezuela, Jamaica, Cayman Islands, Cuba, Yucatán Peninsula, Louisiana, Mississippi | $1.28 billion | 19 (3) | |||

| Josephine | September 17–19 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1006 | None | None | None | |||

| Kyle | September 20 – October 12 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 980 | Bermuda, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, British Isles | $5 million | 0 (1) | |||

| Lili | September 21 – October 4 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 (230) | 938 | Windward Islands, Haiti, Cuba, Cayman Islands, Louisiana | $1.16 billion | 13 (2) | |||

| Fourteen | October 14–16 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1002 | Jamaica, Cayman Islands, Cuba | Minimal | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 14 systems | July 14 – October 16 | 145 (230) | 934 | $2.470 billion | 38 (15) | |||||

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 2002

- 2002 Pacific hurricane season

- 2002 Pacific typhoon season

- 2002 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2001–02, 2002–03

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2001–02, 2002–03

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2001–02, 2002–03

- South Atlantic tropical cyclone

- Mediterranean tropical-like cyclone

Notes

References

- William M. Gray; et al. (December 7, 2001). "Extended range forecast of Atlantic seasonal hurricane activity and US landfall strike probability for 2002". Colorado State University. Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- Climate Prediction Center (August 8, 2006). "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010. Retrieved December 8, 2006.

- "North Atlantic Ocean Historical Tropical Cyclone Statistics". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- William M. Gray; et al. (April 5, 2002). "Extended range forecast of Atlantic seasonal hurricane activity and US landfall strike probability for 2002". Colorado State University. Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- "NOAA: 2002 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 20, 2002. Archived from the original on September 20, 2008. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Klotzbach, Philip J.; Gray, William M. (August 7, 2002). "Updated Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2002". Colorado State University. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- "NOAA: 2002 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 8, 2002. Archived from the original on September 20, 2008. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- "Colorado State Team issues first Post-August storm season update and September-only hurricane forecast – Reduces prediction". Colorado State University. September 3, 2002. Archived from the original on February 28, 2003. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- Aarti Shah (July 15, 2002). "Storm may be brewing off coast". The News and Observer. Raleigh, North Carolina. p. 10B – via Newspapers.com.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Ken Graham (2021). "Record Breaking Hurricane Season 2020 and What's New for 2021" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

-

- Peter Bowyer (2003). "A Climatology of Hurricanes for Canada: Improving Our Awareness of the Threat". Canadian Hurricane Centre. Archived from the original on February 6, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2008.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 44 (8). August 2002. ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 7, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2021. : 98, 99, 131, 172

- Jack Beven (November 20, 2002). Tropical Storm Bertha Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 44 (8). September 2002. ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 7, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2021. : 115

- Jack Beven (January 14, 2003). Hurricane Gustav Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- James L. Franklin; Jamie R. Rhome (December 16, 2002). Tropical Storm Hanna Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Cenapred, Cepal y Servicio Sismológico Nacional (2008). Principales desastres naturales, 1980–2005 (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). El Almanaque Mexicano. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 3, 2011. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Lixion A. Avila (July 2, 2003). Hurricane Isidore Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Stacy R. Stewart (November 16, 2002). Hurricane Kyle Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Miles B. Lawrence (April 10, 2011). Hurricane Lili Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Tropical Storm Lili Situation Report No. 2. Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency (Report). Relief Web. October 1, 2002. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- "Lili killed 4 in Haiti; deaths unreported for a week". USA Today. Associated Press. October 5, 2002. Archived from the original on May 22, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Pan American Health Organization (September 30, 2002). Hurricane Lili in the Caribbean: Hurricane Lili Report #1 (Report). World Health Organization. Archived from the original on April 16, 2005. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Jeff Masters (December 1, 2020). "A look back at the horrific 2020 Atlantic hurricane season". Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- "Tropical Cyclones – September 2002". National Centers for Environmental Information. October 2002. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. June 2019. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Miles B. Lawrence (August 20, 2002). Tropical Storm Arthur Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Roth, David (December 3, 2002). "Tropical Storm Arthur – July 9–15, 2002". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- Peter Bowyer (2003). "A Climatology of Hurricanes for Canada: Improving Our Awareness of the Threat". Canadian Hurricane Centre. Archived from the original on February 6, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2008.

- Jack Beven (November 20, 2002). Tropical Storm Bertha Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- "Damage report on Bertha" (PDF). Louisiana State University. 2002. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- James L. Franklin (August 22, 2002). Tropical Storm Cristobal Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- "Damage Report on Cristobal" (PDF). Louisiana State University. 2002. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- Lixion A. Avila (October 12, 2002). Tropical Storm Dolly Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Lixion A. Avila (August 29, 2002). "Tropical Depression Four Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Lixion A. Avila (August 29, 2002). "Tropical Storm Dolly Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 4, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Jack Beven (August 29, 2002). "Tropical Storm Dolly Discussion Three". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Lixion A. Avila (August 30, 2002). "Tropical Storm Dolly Discussion Six". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Lixion A. Avila (August 31, 2002). "Tropical Storm Dolly Discussion Nine". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Richard J. Pasch (January 16, 2003). "Tropical Storm Edouard" (PDF). Tropical Cyclone Report. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Roth, David M (January 3, 2023). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Stacy R. Stewart (June 23, 2003). Tropical Storm Fay Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Red Cross (September 9, 2002). "Tropical Storm Fay strikes south Texas". Red Cross. Archived from the original on August 27, 2008. Retrieved August 10, 2008.

- "Maestro damage report on Fay" (PDF). Louisiana State University. 2002. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- Miles B. Lawrence (October 30, 2002). Tropical Depression Seven Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Lixion Avila; Martin Nelson (September 7, 2002). "Tropical Depression Seven Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- Miles Lawrence (September 7, 2002). "Tropical Depression Seven Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- Richard Pasch (September 8, 2002). "Tropical Depression Seven Discussion Four". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- Miles Lawrence (September 8, 2002). "Remnant Low Seven Discussion Five". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- Jack Beven (January 14, 2003). Hurricane Gustav Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- "Hurricane Gustav Storm Summary". Canadian Hurricane Centre. October 7, 2002. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- "Newfoundland hit with heavy rain, Gustav leaves land". CTV. September 12, 2002. Archived from the original on June 12, 2022. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- James L. Franklin; Jamie R. Rhome (December 16, 2002). Tropical Storm Hanna Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- "Tropical Storm Event Report for Alabama". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on September 8, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- "Hanna washes ashore, quickly weakens in Alabama". USA Today. Associated Press. September 15, 2002. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- Lixion A. Avila (July 2, 2003). Hurricane Isidore Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Cenapred, Cepal y Servicio Sismológico Nacional (2008). Principales desastres naturales, 1980–2005 (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). El Almanaque Mexicano. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 3, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2009.

- David M. Roth. Black Background, color-filled rainfall graphic for Isidore. Archived September 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved on August 10, 2008.

- "Isidore pummels Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula". USA Today. September 24, 2002. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- John L. Beven II, Richard J. Pasch and Miles B. Lawrence. (December 23, 2003) Atlantic Hurricane Season of 2002. Archived April 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine NOAA. Retrieved on August 10, 2008.

- Richard J. Pasch (January 14, 2003). Tropical Storm Josephine Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Richard J. Pasch (September 17, 2002). "Tropical Depression Eleven Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Stacy Stewart (September 18, 2002). "Tropical Storm Josephine Discussion Three". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Richard J. Pasch (September 18, 2002). "Tropical Storm Josephine Discussion Four". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Richard J. Pasch (September 18, 2002). "Tropical Storm Josephine Discussion Six". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Jack Beven (September 19, 2002). "Extratropical Storm Josephine Discussion Eight". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Stacy R. Stewart (November 16, 2002). Hurricane Kyle Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- "Weather Summary for October 2002". BermudaWeather. November 4, 2002. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- David Roth (December 24, 2006). "Tropical Storm Kyle – October 10–12, 2002". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- "Tropical Storm Kyle". South Carolina State Climatology Office. Archived from the original on February 10, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- Kevin Boyle (2003). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary". Australian Severe Weather. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- Miles B. Lawrence (April 10, 2011). Hurricane Lili Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- National Weather Service Lake Charles (2002). "Lili Preliminary Storm Report". National Weather Service. Archived from the original on April 17, 2003. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- Jack Beven (November 20, 2002). Tropical Depression Fourteen Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- "Tropical Cyclone Names". Archived from the original on October 1, 2002. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- National Hurricane Center (2008). "Worldwide Tropical Cyclone Names". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 4, 2008. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

External links

- Monthly Weather Review

- National Hurricane Center 2002 Atlantic hurricane season summary

- U.S. Rainfall from Tropical Cyclones in 2002