1988 Atlantic hurricane season

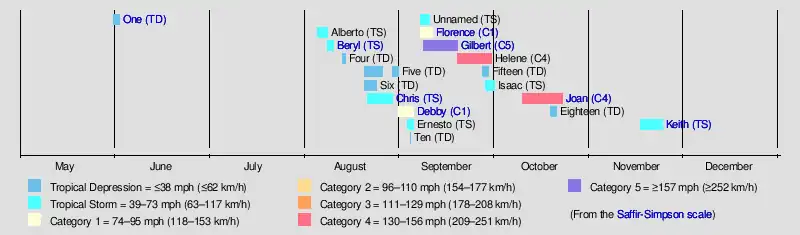

The 1988 Atlantic hurricane season was a near average season that proved costly and deadly, with 15 tropical cyclones directly affecting land. The season officially began on June 1, 1988, and lasted until November 30, 1988, although activity began on May 30 when a tropical depression developed in the Caribbean. The June through November dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. The first cyclone to attain tropical storm status was Alberto on August 8, nearly a month later than usual.[1] The final storm of the year, Tropical Storm Keith, became extratropical on November 24. The season produced 19 tropical depressions of which 12 attained tropical storm status. One tropical storm was operationally classified as a tropical depression but was reclassified in post-analysis. Five tropical cyclones reached hurricane status of which three became major hurricanes reaching Category 3 on the Saffir–Simpson scale.

| 1988 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 31, 1988 |

| Last system dissipated | November 24, 1988 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Gilbert (Most intense hurricane in the Atlantic basin at the time) |

| • Maximum winds | 185 mph (295 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 888 mbar (hPa; 26.22 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 19 |

| Total storms | 12 |

| Hurricanes | 5 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 601–719 total |

| Total damage | $4.99 billion (1988 USD) |

| Related articles | |

There were two notable cyclones of the season, the first one being Hurricane Gilbert, which at the time was the strongest Atlantic hurricane on record. The hurricane tracked through the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico and caused devastation in Mexico and many island nations, particularly Jamaica. Its passage caused $2.98 billion in damage (1988 USD)[nb 1] and more than 300 deaths, mostly in Mexico. The second one was Hurricane Joan, which struck Nicaragua as a Category 4 hurricane and caused about US$1.87 billion in damage and more than 200 deaths. The hurricane crossed into the eastern Pacific Ocean and was reclassified as Tropical Storm Miriam. Hurricane Debby also successfully crossed over, becoming Tropical Depression Seventeen-E, making the 1988 season the first on record in which more than one tropical cyclone has crossed between the Atlantic and Pacific basins intact.[2]

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

| CSU[3] | June | 11 | 7 | Unknown |

| Record high activity[4] | 30 | 15 | 7 (Tie) | |

| Record low activity[4] | 1 | 0 (tie) | 0 | |

| Actual activity | 12 | 5 | 3 | |

Forecasts of hurricane activity are issued before each hurricane season by noted hurricane experts such as Dr. William M. Gray and his associates at Colorado State University. A normal season as defined by NOAA has six to fourteen named storms of which four to eight reach hurricane strength and one to three become major hurricanes. The June 1988 forecast was that eleven storms would form and that seven would reach hurricane status. The forecast did not specify how many hurricanes would reach major hurricane status.[3]

Seasonal summary

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1,[1] but activity in 1988 began two days earlier with the formation of Tropical Depression One on May 30. It was an above average season in which 19 tropical depressions formed.[5] Twelve depressions attained tropical storm status, and five of these attained hurricane status, of which three reached major hurricane status. Four hurricanes and three tropical storms made landfall during the season and caused 550 deaths and $4.86 billion in damage. The last storm of the season, Tropical Storm Keith, dissipated on November 24,[6] only 6 days before the official end of the season on November 30.[1]

The activity in the first two months of the season was limited because of strong wind shear from an upper tropospheric flow. Although vigorous tropical waves moved off the coast of Africa, most of them quickly diminished in intensity as they crossed the tropical Atlantic Ocean. As a result, no tropical depressions formed in June or July. Decreased wind shear in August allowed tropical waves to develop into tropical cyclones.[5] The official storm track forecast errors were 30 to 40 percent lower than the average for the previous 10 years.[6] The 24-, 48-, and 72-hour forecasts were the most accurate in more than 18 years and were also more accurate than in each subsequent season until 1996.[7]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 103, which is classified as "near normal".[8][9] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 34 knots (39 mph; 63 km/h), which is tropical storm strength.[9]

Systems

Tropical Depression One

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 31 – June 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min); 1002 mbar (hPa) |

The first tropical depression of the season formed on May 30 in the northwest Caribbean Sea. The system encountered unfavorable conditions as it moved northward toward Cuba, and a reconnaissance airplane sent to investigate it could not find a well-defined center.[10] The depression remained weak and degenerated on June 2 into an open trough of low pressure in the Florida Straits.[5]

Rainfall from the depression and its precursor peaked at 40.35 in (1,025 mm), including a daily peak of 34.13 in (867 mm).[11] The rainfall most affected the province of Cienfuegos, though the provinces of Villa Clara, Sancti Spíritus, Ciego de Ávila, and Camagüey were also impacted.[12] A tornado in the city of Camagüey destroyed five Soviet planes and multiple buildings.[13] Flooding prompted officials to use rescue crews, helicopters, and amphibious vehicles to evacuate 65,000 residents in low-lying areas to higher grounds. The storm left many without power and communications, severely damaged the country's transportation infrastructure, and destroyed six bridges.[13] Flooding from the depression damaged 1,000 houses and destroyed 200 homes in Camagüey Province alone.[14] Throughout Cuba, the depression affected about 90,000 people, injuring dozens[15] and killing a total of 37 people,[12] including three who died from electrocution.[13] In Florida, the depression produced light rain, including 3.18 in (81 mm) at Pompano Beach.[16]

Tropical Storm Alberto

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 5 – August 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1002 mbar (hPa) |

The season's first named storm originated on August 4 within a weak trough of low pressure that formed off the coast of South Carolina. The next day a low level circulation was detected by satellite, indicating that a tropical depression was forming. By August 6 the storm was designated the second tropical depression of the season.[6] An approaching weak frontal trough pushed the depression northeastward and enhanced its upper-level outflow. On August 7 the system was designated Tropical Storm Alberto at 41.5°N, while located just south of Nantucket, Massachusetts, becoming the northernmost system to intensify into a tropical storm on record.[17][nb 2] The storm accelerated northeastward at 29 mph (47 km/h) and struck western Nova Scotia that evening with little impact.[17][18] On August 8 Alberto became extratropical over the cold waters of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Shortly thereafter it dissipated just north of Newfoundland.[17]

The storm produced peak wind gusts of 48 mph (77 km/h) at Yarmouth, Nova Scotia. Rainfall reached 1.78 inches (45 mm) in Saint John, New Brunswick,[18] most of which fell in a short amount of time. The rainfall caused localized flooding, which briefly closed some streets.[19] The extratropical remnants of Alberto also produced light rain and some clouds along western Newfoundland.[18]

Tropical Storm Beryl

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 8 – August 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1001 mbar (hPa) |

The third tropical depression of the season formed on August 7 from a surface low over southeastern Louisiana. The slow moving system organized as it drifted toward the mouth of the Mississippi River. It soon had enough convective organization for the National Hurricane Center (NHC) to issue an initial advisory on Tropical Depression Three.[20] By August 8 surface winds increased enough to issue tropical storm warnings for Louisiana to the Florida Panhandle.[6] Over the open Gulf, Beryl produced sustained winds of minimal tropical storm force and tropical storm force gusts over coastal Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama.[21] Excessive rain fell along the central Gulf Coast, including local amounts of 16 in (410 mm) at Dauphin Island, Alabama.[22]

Maintaining a well-structured outflow, Beryl's circulation on August 9 moved over warm water, where conditions were favorable for further intensification. However, a front approached from the northwest and reversed the storm's course into southeastern Louisiana.[22] The next morning Beryl had weakened to a tropical depression as it moved over the Bayou Teche. Heavy downpours from system's remnants brought more than 12 in (300 mm) of rain to parts of eastern Texas. Overall damage from the storm was light, and only one known death was attributed to the storm.[23]

Tropical Depression Four

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 13 – August 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1012 mbar (hPa) |

On August 12 a westward-moving tropical wave developed into Tropical Depression Four near the southern Bahamas. The depression tracked north-northwest along Florida's coast and made landfall near Jacksonville, Florida, the next day.[5][24] The system spawned gusty winds and thunderstorms along the coasts of Florida and Georgia but caused little damage.[24] The storm moved over south Georgia and the central Gulf Coast while dropping up to 7 in (180 mm) of rain on the Southeast.[25] According to the National Weather Service, winds in some squalls to the north and east of the center reached up to 50 mph (80 km/h).[26] The system finally dissipated as it reemerged over water near the mouth of the Mississippi.[25]

Early predictions from hurricane forecasters said that the depression would strengthen into the season's third tropical storm.[27] Because of unfavorable upper-level conditions and interaction with Bahama islands, the system lost its well defined center as it moved towards Florida's east coast.[24]

Tropical Depression Five

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 20 – August 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1006 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave in the far eastern Atlantic developed into the fifth tropical depression on August 20. The storm drifted north-northwest of the Cape Verde islands for the next three days with little change in strength.[5] Forecasters were concerned because the depression formed in the breeding ground where other powerful East Coast hurricanes have started. Though the storm was still very weak, they initially predicted it would strengthen.[28]

By August 24 the depression's forward speed had increased to 15 mph (24 km/h) as its movement turned west. Cool ocean temperatures weakened the system and diminished its prospects for restrengthening,[29] and on August 26 Tropical Depression Five degenerated into a tropical wave. The remnants redeveloped on August 30 about 180 miles (290 km) southeast of North Carolina,[5] and the Washington office of the National Weather Service continued to track the system as a gale center until it merged with a front off the East Coast on September 1.

Tropical Depression Six

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 20 – August 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1006 mbar (hPa) |

Tropical Depression Six developed from a tropical wave that moved off the northwest African coast on August 12. The system crossed the tropical Atlantic as a wave until it began organizing near 55° W on August 19.[30] The next day this system was designated a tropical depression while it approached the Windward Islands. After crossing the islands, the depression continued westward into the central Caribbean and encountered less-favorable conditions.[31] Though poorly organized on August 21, the depression was expected to strengthen into a tropical storm over the western Caribbean's warmer waters. Nevertheless, it was downgraded to a tropical wave at 80° W near the island of Jamaica on August 23.[32] The disturbance moved over Central America with minimal convection but redeveloped into Hurricane Kristy once it reached the eastern Pacific.[30] The system's main effect on land was squally weather on the Windward Islands.[5]

Tropical Storm Chris

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 21 – August 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

Chris formed from a strong tropical wave that moved off the west coast of Africa on August 15. By August 21 convection in the northern part of the wave detached and organized into Tropical Depression Seven.[33] The storm tracked westward along the southern periphery of a subtropical high pressure ridge over the mid-Atlantic. For the next seven days, surface and reconnaissance observations found little evidence that the storm was strengthening.[33] As a result, it remained a tropical depression as it moved across portions of the Lesser and Greater Antilles as well as the Bahamas.[34]

The depression passed south of Puerto Rico on August 24 and dumped more than 14 in (360 mm) of rain on parts of the island.[35] Three deaths in Puerto Rico were attributed to the weather.[36] On August 28 the storm was upgraded to Tropical Storm Chris as it traveled northward just offshore of Florida. It made landfall near Savannah, Georgia, bringing light rain and wind damage to the area.[36] Weakening to a depression, Chris poured heavy rains on South Carolina, where it merged with a cold front and became extratropical. The low accelerated over the Eastern Seaboard through Nova Scotia and finally dissipated on August 30.[35] Heavy thunderstorms spawned a tornado in South Carolina that resulted in another death.[33]

Hurricane Debby

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 31 – September 5 (Exited basin) |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 987 mbar (hPa) |

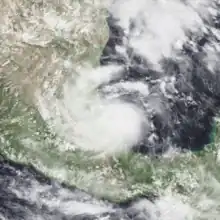

Debby formed from the southern part of a tropical wave that became Tropical Storm Chris. In the mid-tropical Atlantic, the northern area of convection detached and became Tropical Depression Seven. The southern portion continued moving westward as a disorganized area of showers.[6] The system did not develop until the low-level center emerged from the Yucatán into the Bay of Campeche on August 31. It is estimated that the storm became Tropical Depression Eight just offshore at around 12 p.m. local time.[37]

Drifting west-northwest over the Gulf of Mexico, the depression organized and reached tropical storm-strength early on September 2. Later that day, based on observations from aircraft reconnaissance, Debby was upgraded to a hurricane.[37] At peak intensity, the hurricane's center was just 30 mi (48 km) from the coast. With little change in intensity, Debby made landfall near Tuxpan, Veracruz, six hours later.[37] The storm brought high winds, inland flooding, and mudslides and caused 10 deaths.[38]

Debby weakened considerably over the Sierra Madre Oriental mountains, although the remnants continued moving across Mexico. The tight center tracked towards the Pacific coast and reemerged near Manzanillo on September 5. Upon entering the Eastern Pacific, the system became Tropical Depression Seventeen-E before dissipating in the Gulf of California on September 8.

Tropical Storm Ernesto

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 3 – September 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

On September 2 a cluster of thunderstorms associated with a northwestward-moving tropical wave developed a surface low near Bermuda. Though the surface low remained poorly defined and separate from the convection, the system became a tropical depression on September 3.[39] Under the influence of southwesterlies, the depression accelerated northeastward at 50 mph (80 km/h). Late on September 3 it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Ernesto. The storm continued to strengthen as it lost tropical characteristics.[40] A large extratropical storm over the North Atlantic absorbed Ernesto on September 5. The only land area affected by the storm was in the Azores, where it brought near storm-force winds to Flores Island.[6]

Tropical Depression Ten

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 4 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

A broad low-pressure area formed in the western Gulf of Mexico on September 2 and quickly developed through the next day. By September 3 convection was organized enough to declare the system a tropical depression about 160 mi (260 km) west-southwest of Morgan City, Louisiana.[41] Forecasters issued tropical storm warnings for the coast from Cameron, Louisiana, to Apalachicola, Florida, while the storm moved rapidly northeastward at 15 to 20 mph (32 km/h).[5] However, the depression degenerated a few hours later when it merged with the cold front that had caused its acceleration. Oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico reported winds gusts to 40 mph (64 km/h), and moderate to heavy rains drenched large portions of southeast Texas and Louisiana.[5] The wave dampened over the next 24 hours and brought heavy rain to the rest of the southeast, including a maximum of 8.4 in (210 mm) in Biloxi, Mississippi.[42] No major damage was reported.

Unnamed tropical storm

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 7 – September 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

A well-organized disturbance moved off the African coast on September 6 and rapidly developed into Tropical Depression Eleven. The NHC began issuing advisories on September 8 while it was 350 mi (560 km) northeast of Cape Verde. An after-the-fact review of satellite and ship reports indicated that the depression reached tropical storm-strength on September 7.[43][44] However, because of its extreme eastern track, the storm's observational track did not include this information.

For three days a large trough of low pressure northwest of the system steered it north-northwest towards cooler waters. Moderate to heavy rain was reported along the west coast of Africa, but no damage was reported.[43] The system eventually weakened and merged with the low pressure trough. This unnamed storm was later added to the list of tropical storms in the annual summary for the Atlantic hurricane season.[6]

Hurricane Florence

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 7 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 982 mbar (hPa) |

A cloud band accompanying a cold front exited the coast of Texas into the Gulf of Mexico on September 4. The band split into two over the central Gulf when the southern portion stalled and the northern portion developed into a frontal wave that tracked northeastward. Convection over the southern portion increased and wrapped around the center of the cloud band. On September 7 the system formed a surface circulation, and tropical depression advisories began that day.[45]

The depression drifted eastward under the influence of the dissipating frontal trough and intensified into Tropical Storm Florence, as confirmed by hurricane hunters.[45] The storm turned northward on September 9 and accelerated toward the northern Gulf Coast under the influence of a mid- to upper-level trough. Florence became a hurricane just hours before landfall on the western Mississippi Delta.[6] The storm rapidly weakened over southeastern Louisiana and lost all its deep convection as it passed over the New Orleans area. Florence became a depression on September 10 near Baton Rouge and dissipated the next day over northeast Texas.[45]

Early in its duration the system dropped moderate amounts of rainfall across the Yucatán Peninsula.[46] Upon striking Louisiana, storm surge water levels rose moderately above normal just east of where the center moved ashore.[47] Gusty winds caused power outages to more than 100,000 people. In Alabama one man died while trying to secure his boat. Rainfall from the hurricane caused severe river flooding in portions of the Florida Panhandle in an area already severely affected by heavy rainfall, and the flooding damaged or destroyed dozens of houses in Santa Rosa County.[48]

Hurricane Gilbert

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 8 – September 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 mph (295 km/h) (1-min); 888 mbar (hPa) |

The 13th tropical depression formed just east of the Lesser Antilles on September 8. As it moved west-northwest, it became Tropical Storm Gilbert over the islands on September 9. The tropical storm turned west and rapidly intensified to a major hurricane on September 11. Gilbert continued to strengthen as it brushed the southern coast of Hispaniola. It passed directly over Jamaica as a Category 3 hurricane and brought torrential rains to the island's mountainous areas. When the center reemerged over water, Gilbert rapidly intensified again. On September 13 the central pressure dropped 72 millibars (2.1 inHg), the fastest deepening of an Atlantic hurricane on record until 2005's Hurricane Wilma.[49] Gilbert's pressure of 888 millibars (26.2 inHg) at the time was the lowest sea level pressure ever recorded in the Western Hemisphere.[50]

Gilbert weakened slightly before landfall on the Yucatán Peninsula, although it struck at Category 5 strength. As the eye moved over land, the storm rapidly lost strength, reemerging on September 15 in the Gulf of Mexico as a Category 2 hurricane. Hurricane Gilbert continued its northwest track and restrengthened to a minimal Category 4 hurricane. On September 16, Gilbert made its final landfall in northeast Mexico near the town of La Pesca with maximum sustained winds of 125 mph (201 km/h). The center passed south of Monterrey, Mexico, on September 17 and brought heavy flooding to the city. Gilbert's remnants turned north and eventually merged with a developing frontal low pressure system over Missouri.[50]

Hurricane Gilbert was the most intense hurricane ever observed in the Atlantic basin until Hurricane Wilma broke this record in 2005.[49] The storm caused $2.98 billion in damage across the Caribbean and into Central America. Gilbert was the first hurricane to make landfall in Jamaica since Hurricane Charlie in 1951. Until 2007's Hurricane Dean, it was also the most recent storm to make landfall as a Category 5 hurricane in Mexico. The death toll from Gilbert was reported to be 318 people, mostly from Mexico.[51]

Hurricane Helene

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 19 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min); 938 mbar (hPa) |

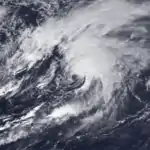

A tropical wave with deeply organized convection crossed the coast of Africa on September 15. The system was forced west due to a strong ridge in the eastern Atlantic. On September 19 at 18:00 UTC, the system was upgraded to Tropical Depression Fourteen. By 06:00 UTC on September 20, the depression was strengthened, and was upgraded to Tropical Storm Helene. Helene began to turn to the northwest on September 21 due to a major trough in the eastern Atlantic. Later on September 21, Helene intensified into a hurricane. Favorable conditions allowed the storm to continue strengthening, and on September 22, Helene became a major hurricane. Late on the following day, Helene attained its peak intensity; maximum sustained winds were at 145 mph (233 km/h) and the minimum pressure of 938 mbar (27.7 inHg).[52]

After reaching peak intensity, Helene weakened as it tracked generally northward through the open Atlantic. By early on September 29, Helene briefly restrengthened into a Category 2 hurricane and reached a secondary peak of 105 mph (169 km/h). However, later that day, Helene weakened back to a Category 1 hurricane while accelerating to the northeast. At 12:00 UTC on September 30, Helene transitioned into an extratropical cyclone while centered well south of Iceland. The precursor tropical wave produced thunderstorms and gusty winds ranging between 23 and 34 mph (37 and 55 km/h) in Cape Verde on September 17.[52]

Tropical Depression Fifteen

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 27 – September 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min); 1009 mbar (hPa) |

While Hurricane Helene was spinning in the central Atlantic, a tropical wave that moved off the coast of Africa in late September rapidly organized. On September 27 the storm became the fifteenth tropical depression of the season while it was about 265 mi (426 km) south-southeast of Cape Verde.[53] The depression tracked westward at 15 to 20 mph (32 km/h) but weakened rapidly. The next day it was downgraded to a tropical wave while still in the far eastern Atlantic, and never reformed in the Atlantic.[5] Aside from a brief threat to the Cape Verde islands, the system remained far from any landmasses throughout its life.

Tropical Storm Isaac

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 28 – October 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on September 23. It traveled westward at a low latitude along the Intertropical Convergence Zone (or ITCZ), and its convection gradually grew more organized.[54] On September 29 it was identified as Tropical Depression Sixteen about 900 mi (1,400 km) southeast of Barbados. The westward path of the storm shifted two degrees northward, possibly as a result of the formation of a new center. On September 30 the depression was upgraded when an Air Force reconnaissance plane discovered tropical storm-force winds.[6] Westerly vertical wind shear prevented deep convection at the center of the storm. As Isaac approached the islands, northern parts of the Lesser Antilles were issued tropical storm warnings.[6] Nevertheless, the storm lasted only a short time in the shearing environment. Isaac was downgraded to a depression on October 1 and completely dissipated shortly thereafter.[54] The remnants of Isaac eventually regenerated in the eastern Pacific Ocean basin as Tropical Depression Twenty-E.[55]

As a tropical cyclone, Isaac did not significantly affect land.[56] However, the remnants dropped heavy rainfall across Trinidad and Tobago, causing flooding and mudslides that injured 20 people[57] and left at least 30 homeless.[58] Flash flooding in Morvant killed two people.[57] Across the country, the storm damaged roads and bridges.[59]

Hurricane Joan

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 10 – October 23 (Exited basin) |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min); 932 mbar (hPa) |

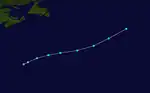

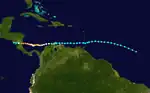

On October 10 the 17th tropical depression of the season organized from a disturbance in the ITCZ. For the next two days the system traveled northwest while it strengthened into Tropical Storm Joan.[60] After passing through the southern Lesser Antilles, Joan traveled westward along the South American coast as a minimal tropical storm. It crossed the Guajira Peninsula on October 17 and quickly attained hurricane strength just 30 mi (48 km) from the coast. Hurricane Joan strengthened into a major hurricane on October 19 while drifting westward. The hurricane executed a tight cyclonic loop in which it weakened greatly but rapidly strengthened upon resuming its westward track.[61] Joan reached its peak intensity just before making landfall near Bluefields, Nicaragua, on October 22 as a Category 4 hurricane. Joan at the time was the southernmost Category 4 hurricane ever recorded, but this record has since been broken by Hurricane Ivan.[62] Joan remained well organized as it crossed Nicaragua and emerged in the eastern Pacific Ocean basin as Tropical Storm Miriam. Miriam gradually weakened until dissipating on November 2.

Hurricane Joan killed 148 people in Nicaragua and 68 others in affected nations.[63] The hurricane damage in Nicaragua amounted to half of the $1.87 billion total. Joan also brought heavy rainfall and mudslides to countries along the extreme southern Caribbean.[61] Its track along the northern coast of South America was very rare; Joan was one of only a few Atlantic tropical cyclones to move in this way.[64] Joan was also the first tropical cyclone to cross from the Atlantic basin since Hurricane Greta of 1978.[65]

Tropical Depression Eighteen

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 19 – October 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1006 mbar (hPa) |

A westward-moving tropical wave, that left the coast of Africa in early October, tracked closely behind Hurricane Joan through the southern Caribbean.[66] In an unusual occurrence the disturbance developed into the 18th tropical depression about 500 mi (800 km) behind the powerful hurricane. An Air Force reconnaissance check of tropical weather on October 19 spotted the depression near Colombia's Guajira Peninsula. Hurricane Joan's small size allowed the depression to remain out-of-reach as it developed. However, the outflow of the hurricane sheared the depression and sapped its energy.[67] The system gradually dissipated on October 21 while Joan was experiencing rapid strengthening just before its arrival on the coast of Nicaragua.[61] The depression brought heavy rain to the Netherlands Antilles.[5] News reports blamed Tropical Depression Eighteen and other tropical systems for bringing swarms of pink locusts from Africa to Trinidad and other Caribbean nations.[66]

Tropical Storm Keith

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 17 – November 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 985 mbar (hPa) |

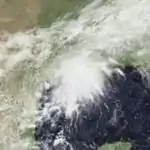

The last storm of the season formed from a tropical wave on November 17 to the south of Haiti. It moved westward through the Caribbean and became organized enough to attain tropical storm status on November 20. Keith rapidly organized and peaked with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) before making landfall on the northeastern portion of the Yucatán Peninsula on November 21. An upper-level trough forced it to the northeast, where upper-level shear and cooler drier air weakened it to minimal storm strength in a pattern typical for November.[6][68] Keith restrengthened over the southeastern Gulf of Mexico and struck near Sarasota, Florida, on November 23. After crossing the state, it became extratropical on November 24 near Bermuda and became an intense extratropical system over the Atlantic with sustained winds of minimal hurricane force.[6][69]

Early in its duration Keith produced moderate to heavy rainfall in Honduras, Jamaica, and Cuba.[70][71][72] Minimal damage was reported in Mexico, still recovering from the devastating effects of Hurricane Gilbert two months earlier.[73] Keith, the last of four named tropical cyclones to hit the United States during the season, produced moderate rainfall, a rough storm surge, and gusty winds across central Florida.[6] Overall damage was widespread but fairly minor, totaling about $7.3 million.[72][74] Damage near the coast occurred mainly from storm surge and beach erosion, while damage further inland was limited to flooding and downed trees and power lines. No fatalities were reported.[72]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms that formed in the north Atlantic in 1988. The names not retired from this list were used again in the 1994 season. This is the same list used for the 1982 season. Storms were named Gilbert, Isaac, Joan and Keith for the first (and only, in the cases of Gilbert and Joan) time in 1988. Florence and Helene were not used in 1982 but had been used in previous lists.

|

Retirement

The World Meteorological Organization retired two names in the spring of 1989: Gilbert and Joan. They were replaced by Gordon and Joyce in the 1994 season.

Season effects

This is a table of all the storms and that have formed in the 1988 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s), denoted in parentheses, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a tropical wave, or a low, and all the damage figures are in 1988 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | May 31 – June 2 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | 1002 | Greater Antilles | Unknown | 37 | [12][75] | ||

| Alberto | August 5 – 8 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1002 | East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada | None | None | |||

| Beryl | August 5 – 8 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1002 | Gulf Coast of the United States | $3 million | 1 | |||

| Four | August 13 – 14 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1012 | Florida | None | None | |||

| Five | August 20 – 31 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1006 | None | None | None | |||

| Six | August 20 – 24 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1006 | Windward Islands | None | None | |||

| Chris | August 21 – 29 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1005 | Leeward Islands, Greater Antilles, East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada | $2.2 million | 6 | |||

| Debby | August 31 – September 8 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 987 | Yucatan Peninsula, Eastern Mexico | Unknown | 20 | |||

| Ernesto | September 3 – 5 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 994 | None | None | None | |||

| Ten | September 4 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1004 | Gulf Coast of the United States | None | None | |||

| Unnamed | September 7 – 10 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 994 | Cape Verde | None | None | |||

| Florence | September 7 – 11 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 982 | Yucatan Peninsula, Gulf Coast of the United States | $2.9 million | 1 | |||

| Gilbert | September 8 – 19 | Category 5 hurricane | 185 (295) | 888 | Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles, Central America, Yucatan Peninsula, South Central, Midwestern and Western Canada | $2.98 billion | 318 | [76][77] | ||

| Helene | September 19 – 30 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 (230) | 938 | None | None | None | |||

| Fifteen | September 27 – 29 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | 1009 | None | None | None | |||

| Isaac | September 28 – October 1 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1005 | Trinidad and Tobago | Unknown | 2 | |||

| Joan | October 10 – 23 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 (230) | 932 | Windward Islands, Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, Colombia, Venezuela, Central America | $2 billion | 216–334 | [77] | ||

| Eighteen | October 19 – 21 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1006 | Netherlands Antilles, Trinidad | None | None | |||

| Keith | November 17 – 24 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 985 | Central America, Yucatán Peninsula, Greater Antilles, Southeastern United States, Southeast United States, Bermuda | $7.3 million | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 19 systems | May 31 – November 24 | 185 (295) | 888 | $4.99 billion | 601–719 | |||||

See also

- 1988 Pacific hurricane season

- 1988 Pacific typhoon season

- 1988 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 1987–88, 1988–89

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 1987–88, 1988–89

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 1987–88, 1988–89

- South Atlantic tropical cyclone

- Mediterranean tropical-like cyclone

Notes

- All damage figures are in 1988 United States dollars, unless otherwise noted

- Although Alberto intensified from a tropical depression to a tropical storm at a higher latitude than any other Atlantic system, it is not the northernmost formation of a tropical cyclone in the Atlantic. That record is held by an unnamed tropical storm in 1952 that formed at 42.0°N, and was not operationally recognized.

References

- National Hurricane Center (2006). "Tropical Cyclone Climatology". Archived from the original on December 13, 2007. Retrieved November 24, 2007.

- Henson, Bob (October 10, 2022). "As Julia fades, floods plague Central America". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- CSU (2006). "Tropical Meteorology Project Forecast Verifications Errors". Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved January 6, 2008.

- "North Atlantic Ocean Historical Tropical Cyclone Statistics". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- Lixion A. Avila; Gilbert B. Clark (October 1988). "Atlantic Tropical Systems of 1988". Monthly Weather Review. 117 (10): 2260. Bibcode:1989MWRv..117.2260A. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1989)117<2260:ATSO>2.0.CO;2.

- Miles B. Lawrence and James M. Gross (1989). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1988" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 14, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (2007). "Average NHC Atlantic Track Forecast Errors" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved January 6, 2008.

- Hurricane Research Division (February 2014). "Atlantic basin: Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- Climate Prediction Center (May 22, 2014). "Background information: the North Atlantic Hurricane Season". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- "Forecasters Watching Depression". Domestic News. Associated Press. June 1, 1988.

- Instituto Nacional de Recursos Hidráulicos (2003). "Lluvias intensas observadas y grandes inundaciones reportadas" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved February 10, 2007.

- "Características generales de los factores del régimen hidrológico de Cuba" (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Recursos Hidráulicos. 2003. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- "Tropical storm leaves 14 dead". Star-News. June 2, 1988. p. 6A. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- "Cuba – Flood". The Russian Information Agency. June 8, 1988.

- "Cuba – Heavy Rains Jun 1988 UNDRO Information Report No. 1". United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs. June 10, 1988. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- David Roth (2006). "Rainfall Summary for Tropical Depression One". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- "Tropical Storm Alberto Preliminary Report" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. 1988. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- "Canadian Tropical Cyclone Season Summary for 1988". Environment Canada. January 15, 2014. Archived from the original on September 16, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- Toronto Star (August 8, 1988). "Tropical storm Alberto fizzles out before hitting N.S.".

- "Tropical Storm Beryl Preliminary Report" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. 1988. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "Tropical Storm Beryl Preliminary Report" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. 1988. p. 2. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- David Roth (2006). "Rainfall Summary for Tropical Storm Beryl". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on September 22, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "Tropical Storm Beryl Preliminary Report" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. 1988. p. 3. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "August 13, 1988, Saturday, BC cycle". United Press International. August 13, 1988.

- David Roth (2006). "Rainfall Summary for Tropical Depression Four". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2007.

- "Depression drifts toward Atlantic coast". Orlando Sentinel. Associated Press. August 13, 1988. p. A–3. Retrieved May 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Frank T. Csongos (August 14, 1988). "August 14, 1988, Sunday, AM cycle". United Press International.

- "Two tropical depressions form". United Press International. August 20, 1988. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- "Third Depression Forms In Tropical Atlantic". Sun-Sentinel. Associated Press. August 23, 1988. p. 3A. Retrieved September 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane Kristy Preliminary Report" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. 1988. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- "August 21, 1988, Sunday, BC cycle". Domestic News. United Press International. August 21, 1988.

- "August 23, 1988, Tuesday, AM cycle". Domestic News. United Press International. August 23, 1988.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Tropical Storm Chris Preliminary Report". p. 1. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - David Roth (2006). "Rainfall Summary for Tropical Storm Chris". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on September 22, 2013. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Tropical Storm Chris Preliminary Report". p. 2. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Hurricane Debby Preliminary Report". p. 1. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Hurricane Debby Preliminary Report". p. 2. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Tropical Storm Ernesto Preliminary Report". p. 1. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Tropical Storm Ernesto Preliminary Report". p. 3. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

- Sandra Walewski (September 3, 1988). "Tropical Depression Forms In Gulf; Tropical Storm Develops In Atlantic". Domestic News. Associated Press.

- David Roth (2006). "Rainfall Summary for Tropical Depression Ten". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Unnamed Tropical Storm Preliminary Report". p. 1. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Unnamed Tropical Storm Preliminary Report". p. 4. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

- "Hurricane Florence Preliminary Report" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. 1988. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 29, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2007.

- David Roth (2006). "Rainfall Summary for Hurricane Florence". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2007.

- "Hurricane Florence Preliminary Report" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. 1988. p. 2. Archived from the original on October 29, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2007.

- "Hurricane Florence Preliminary Report" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. 1988. p. 3. Archived from the original on October 29, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (2006). "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Wilma" (PDF). NOAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 25, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Hurricane Gilbert Preliminary Report". p. 3. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Hurricane Gilbert Preliminary Report". p. 2. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- Robert A. Case (1988). "Hurricane Helene Preliminary Report". National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- "Hurricane Helene Clings To Life". Domestic News. Associated Press. September 27, 1988.

- "Tropical Storm Isaac Preliminary Report" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. 1988. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 21, 2007.

- "Tropical Depression Twenty-E Discussion for 0300 UTC" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. October 11, 1988. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 21, 2007.

- Miles B. Lawrence (October 30, 1988). "Tropical Storm Isaac Preliminary Report" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- Lindsay Mackoon (October 2, 1988). "Storm wreaks havoc on Trinidad". United Press International. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- Staff Writer (October 4, 1988). "2 die as storm lashes islands". Saint Petersburg Times. Retrieved September 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- World Loss Report (October 21, 1988). Occurrence and reports: Natural Catastrophe (Report).

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Hurricane Joan Preliminary Report". p. 7. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Hurricane Joan Preliminary Report". p. 2. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (2005). "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Ivan". Archived from the original on September 11, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Hurricane Joan Preliminary Report". p. 3. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Hurricane Joan Preliminary Report". p. 1. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- NOAA (2007). "FAQ Part E: Tropical Cyclone Records". p. 1. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- Pierre Yves-Glass (October 20, 1988). "Locust Invasion Threatens Caribbean Crops". International News. Associated Press.

- "October 21, 1988, Friday, PM cycle". Domestic News. United Press International. October 21, 1988.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Tropical Storm Keith Preliminary Report". p. 1. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2008.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Tropical Storm Keith Preliminary Report". p. 2. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- "Late-Season Storm Forms; Cuba, Florida Likely Targets". The Daily Register. Associated Press. November 21, 1988. p. 5A. Retrieved September 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Brian Murphy (November 22, 1988). "Storm Keith Hovers In Gulf, Could Strike Florida". Journal Gazette. Associated Press. p. A-6. Retrieved September 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- National Hurricane Center (1988). "Tropical Storm Keith Preliminary Report". p. 3. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- The Globe and Mail (Canada) (November 22, 1988). "Tropical storm Keith hits Yucatan, western Cuba".

- Thomas C. Tobin (December 7, 1988). "Damage from Keith won't qualify for aid". Saint Petersburg Times. p. 3. Retrieved May 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Avila, Lixion A; Clark, Gilbert B (October 1, 1989). "Atlantic Tropical Systems of 1988". Monthly Weather Review. 117 (10): 2260–2265. Bibcode:1989MWRv..117.2260A. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1989)117<2260:ATSO>2.0.CO;2.

- Blake, Eric S; Landsea, Christopher W; Gibney, Ethan J; National Hurricane Center (August 2011). The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (And Other Frequently Requested Hurricane Facts) (PDF) (NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC-6). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. p. 47. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 31, 2012. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- Lawrence, Miles B; Gross, James M (October 1, 1989). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1988" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 117 (10): 2248–2259. Bibcode:1989MWRv..117.2248L. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1989)117<2248:AHSO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0493. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 4, 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

External links

- Monthly Weather Review

- Detailed information on all storms from 1988

- Information concerning U.S. rainfall from tropical cyclones in 1988

- HURDAT archive on 1988 season