Tropical Storm Kirk (2018)

Tropical Storm Kirk was the second lowest-latitude tropical storm on record in the Atlantic basin. The eleventh named storm of the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season, Kirk originated from a tropical wave that left Africa on September 20 and organized into a tropical depression two days later. The system intensified into Tropical Storm Kirk early on September 22 but quickly degenerated into a tropical wave again early the next day. A reduction in the disturbance's forward speed allowed it to regain tropical storm intensity on September 26. Kirk reached maximum sustained winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) that morning before increasing westerly wind shear caused the cyclone to steadily weaken. The storm made landfall on Saint Lucia with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) before continuing into the Caribbean Sea. Kirk degenerated to a tropical wave again on September 28, and its remnants continued westward, contributing to the formation of Hurricane Michael ten days later.

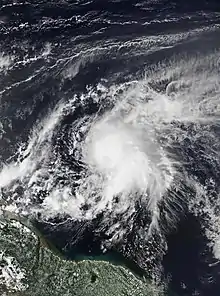

Tropical Storm Kirk at peak intensity on September 26 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 22, 2018 |

| Dissipated | September 28, 2018 |

| Tropical storm | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 65 mph (100 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 998 mbar (hPa); 29.47 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 2 total (presumed) |

| Damage | At least $440,000 (2018 USD) |

| Areas affected | Barbados, Windward Islands, Guadeloupe |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Kirk passed narrowly north of Barbados, where tropical storm-force winds cut power to multiple neighborhoods and caused property damage at the official residence of the Governor-General. Rainfall in excess of 10 inches (250 mm) flooded structures and vehicles, prompting 11 emergency water rescues. In Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, rough seas caused coastal flooding and led to the presumed deaths of two fishermen after they ventured out during the storm. On Saint Lucia, strong winds destroyed two buildings; additional structures, including schools and the anemometer at the Hewanorra International Airport, sustained damage. About 2,000 chickens on a poultry farm were killed following the collapse of their pens, and about 80–90% of the island's banana crop was left in ruin. The combination of winds and landslides prompted widespread power outages. Lesser impacts were felt on Martinique, where winds damaged trees and cut power to about 3,000 homes.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

A low-latitude tropical wave departed the western coast of Africa late on September 20 and moved rapidly west-northwest. After two days of sporadic convective development, it acquired sufficient organization to be declared a tropical depression by the National Hurricane Center (NHC) around 06:00 UTC on September 22 to the south of Cabo Verde. Six hours later, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Kirk at 8.1°N, representing the second lowest-latitude tropical storm on record in the Atlantic; only the third storm of the 1902 hurricane season formed farther south. A subtropical ridge to the north of the newly formed cyclone expanded westward, directing the system in the same direction. Kirk became less organized over the next day as a large band of convection, similar to an outflow boundary, propagated away from the center into the northwestern quadrant. This cloud pattern suggested the entrainment of mid-level dry air. The hostile environment caused Kirk to degenerate into a tropical wave by 12:00 UTC on September 23.[1] Even after degeneration, the storm's remnants continued to produce a large area of showers and thunderstorms, along with gale-force winds in the northern quadrant.[2]

By September 26, the forward motion of the remnants slowed, allowing convection to coalesce about a new well-defined center. The NHC accordingly re-initiated Kirk as a tropical storm around 00:00 UTC on September 26 about 520 miles (835 km) east-southeast of Barbados. By the morning hours, Kirk's presentation had evolved to feature a strong central dense overcast with few banding features.[3] Satellite intensity estimates were used to assign a peak intensity of 65 mph (105 km/h) at 12:00 UTC through 18:00 UTC on September 26. Thereafter, the cyclone's presentation morphed into a comma-shaped appearance, with the center at times partially exposed on the western edge of this convection due to increasing westerly wind shear.[4] Kirk temporarily moved west-northwest, passing just north of Barbados, before banking west-southwest under the dominant steering regime of a ridge in the western Atlantic. It struck Saint Lucia as a 50 mph (80 km/h) tropical storm around 00:30 UTC on September 30 and entered the Caribbean, where the storm resumed a west-northwest course while continuing to lose strength. By 00:00 UTC on September 29, after a reconnaissance aircraft was unable to locate a well-defined and closed center, the NHC downgraded Kirk to a tropical wave again while it was positioned a few hundred miles south of the United States Virgin Islands.[1] The remnants continued into the western Caribbean, where they were absorbed by a large area of disturbed weather by October 2 and contributed to the formation of Hurricane Michael.[5]

Preparations

At 09:00 UTC on September 26, tropical storm warnings were raised for Barbados and Saint Lucia, accompanied by tropical storm watches for Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. Three hours later, additional tropical storm warnings were issued for Dominica, Martinique, and Guadeloupe. At 12:00 UTC on September 28, all tropical storm warnings were discontinued; three hours later, all watches were discontinued as well.[1] In advance of the storm system, LIAT, Caribbean Airlines, and Air Antilles canceled or rescheduled numerous flights between Caribbean destinations.[6][7][8] Schools were closed on September 27 and 28 in Barbados, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saint Lucia, Martinique, Dominica, and Guadeloupe.[9][10][11][12][13] In Dominica, all 113 hurricane shelters were opened from September 26–28, and businesses were closed on September 27. Water service was temporarily suspended there as a precaution.[11]

Impact

Barbados

Kirk produced sustained winds of 40 mph (64 km/h), gusting to 46 mph (74 km/h), on Barbados as it passed within 40 miles (64 km) of the island.[1] Rainfall in excess of 10 in (250 mm) caused extensive flooding of streets and homes, peaking on the night of September 27–28 on the back end of the storm system.[14] In some parts of Christ Church, floodwaters rose to 5 ft (1.5 m) in depth,[15] forcing some motorists to abandon their cars.[14][16] In total, 11 individuals in Saint Philip, Christ Church, and Bridgetown required emergency water rescue by the Barbados Defence Force.[17][18] The Barbados Light and Power Company reported power cuts in multiple neighborhoods.[19] Kirk also damaged a stone wall on the property of the Government House.[18] About 40 of the 110 buses owned by Barbados Transport Board were removed from service to allow for repairs of water-related damage incurred while driving through flooded streets.[20] This contributed to long delays for commuters in the following days.[21] A stretch of beach on the south coast was closed until the evening of October 1 so the sluice gate that regulates the Graeme Hall Swamp could be opened to release excess rainwater.[22] In the immediate aftermath of the flooding, Prime Minister Mia Mottley toured the hardest-hit communities with a team of government officials to assess the situation.[23] On October 19, the government of Barbados received an insurance payout of about Bds$11.6 million (US$5.8 million) from CCRIF SPC to cover flood damage.[24][25]

Windward Islands

Heavy rainfall and resultant river flooding also affected northeastern Saint Vincent, with precipitation totals exceeding 4 in (100 mm). Coastal flooding due to high surf forced three families to evacuate their homes in New Sandy Bay Village and seek shelter in a public school.[11][26] Two fishermen disappeared and were presumed dead after they ignored weather advisories set out from Canouan during the storm.[26]

Strong winds, sustained at 46 mph (74 km/h) and gusting to 62 mph (100 km/h),[1] brought down trees and power lines on Saint Lucia, disrupting power and communications services to hundreds of homes.[11][27] Some additional power outages were caused by minor landslides.[28] Electric service was fully restored by late on September 30, after crews completed repairs that included replacing broken utility poles.[29] Several buildings were damaged and at least two were destroyed;[11] schools sustained an estimated EC$1.2 million (US$440,000) in damage. The strong winds also destroyed an anemometer at Hewanorra International Airport.[30] Following the storm, the Saint Lucia Red Cross provided blankets, tarpaulins, and other emergence supplies to households impacted by Kirk.[31] Agricultural interests took a hard hit, particularly in northern parts of the island;[11] many banana fields were ravaged, leading to an 80–90% loss of that crop on the island.[30][32] In Babonneau, some 2,000 chickens on a poultry farm were killed when their pens collapsed.[33]

In some cases, farmers were not covered under their insurance plans because Kirk fell just below intensity thresholds stipulated for tropical cyclone compensation.[34] Taiwan's International Cooperation and Development Fund (ICDF) contributed EC$1.4 million (US$518,000) in relief funds to be distributed among 108 farmers on Saint Lucia.[34] This donation marked the beginning of the Banana Productivity Improvement Project, a joint program between the ICDF and the Saint Lucia government to support and educate farmers.[35] For instance, it was observed that banana farms shielded by windbreaks fared much better during Tropical Storm Kirk than exposed fields, so with additional ICDF funding, thousands of mango trees were planted as barriers against future wind storms, and growers were counseled on how to care for the trees.[36]

Gusty winds extended northward to Martinique; weather stations at standard 33-foot (10 m) elevation recorded sustained winds of 41 mph (66 km/h), gusting to 58 mph (93 km/h). One station at higher elevation observed a peak gust to 69 mph (111 km/h).[1] The winds damaged trees and cut power to 3,000 homes, mostly in Le Robert, Sainte-Marie, Gros-Morne, and Le Morne-Vert communes, and the capital city of Fort-de-France.[37] In Saint-Esprit, a sports complex sustained roof damage that required two days of expedited work to repair.[38] Some residents of Le Prêcheur had to flee a dangerous lahar triggered by heavy rains.[39] During his four-day tour of the French West Indies, President of France Emmanuel Macron canceled a planned visit to Fort-de-France in response to the storm.[40] Guadeloupe experienced lighter winds but more significant rainfall than Martinique, with precipitation totals reaching 6.81 in (173 mm) at Petit-Bourg.[41]

See also

- 2018 Atlantic hurricane season

- Other storms of the same name

- Tropical Storm Danielle (1986), a low-tracked storm that alongside another system produced extensive damage on Saint Vincent

- Tropical Storm Earl (2004), a short-lived tropical storm that impacted the Windward Islands in August 2004

- Tropical Storm Bret (2017), the earliest tropical storm on record in the Atlantic's Main Development Region that struck Trinidad and Tobago

References

- Eric S. Blake (January 29, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Kirk (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- Michael J. Brennan (September 24, 2018). "Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- Richard J. Pasch (September 26, 2018). "Tropical Storm Kirk Discussion Number 11". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- Richard J. Pasch (September 26, 2018). "Tropical Storm Kirk Discussion Number 12". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- John L. Beven II; Robbie J. Berg; Andrew B. Hagen (May 17, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Michael (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Press release (September 26, 2018). "LIAT cancels flights due to Tropical Storm Kirk". The Daily Nation. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Darlisa Ghouralal (September 26, 2018). "CAL cancels flights as Tropical Storm Kirk strengthens". Loop News Barbados. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Sullyvan Daphné (September 27, 2018). "Tempête tropicale Kirk : Air Antilles modifie le programme de ses vols". RCI Martinique (in French). Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Heather-Lynn Evanson (September 28, 2018). "Schools closed today". The Daily Nation. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Tropical Storm Kirk drops heavy rain across eastern Caribbean". CTV News. Associated Press. September 27, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Tropical Storm Kirk Situation Report #1 (PDF) (Report). Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency. September 28, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Schools closed in St Lucia Thursday and Friday as Kirk passes". Loop News St. Lucia. September 28, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Tempête tropicale Kirk : passage en alerte cyclonique orange" (in French). République Française. September 28, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Heather-Lynn Evanson (September 28, 2018). "Tail hits hard". The Daily Nation. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Alex Downes (September 28, 2018). "Three saved by BDF team". The Daily Nation. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Carol Martindale and Antoinette Connell (September 28, 2018). "Homes flooded in Wotton". The Daily Nation. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Heather-Lynn Evanson (September 28, 2018). "Marshall on tour after Kirk". The Daily Nation. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Christina Smith (September 28, 2018). "No need for national shutdown, says Marshall". Loop News Barbados. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Heather-Lynn Evanson (September 28, 2018). "Several districts without power". The Daily Nation. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Bea Dottin (October 3, 2018). "40 buses affected by Tropical Storm Kirk". The Daily Nation. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Sandy Deane (October 4, 2018). "'Blame Kirk'". Barbados Today. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Beaches closed for a longer period due to Tropical Storm Kirk". Loop News Barbados. September 29, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Tre Greaves (September 29, 2018). "PM touring areas affected by flooding". The Daily Nation. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Emmanuel Joseph (October 19, 2018). "'Kirk' floods $21 million payout". Barbados Today. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Government to receive US$5 million for TS Kirk". Loop News Barbados. October 18, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- British Caribbean Territories (February 14, 2019). Country Report: British Caribbean Territories (PDF) (Report). Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Caroline Popovic (September 28, 2018). "La tempête tropicale Kirk fait des dégâts à Sainte-Lucie". France Info (in French). Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "Tropical Storm Kirk Electricity System Update #1". LUCELEC. September 28, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Tropical Storm Kirk Electricity System Update #5". LUCELEC. October 2, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- RA IV Hurricane Committee Members (February 12, 2019). Country Report: Saint Lucia (PDF) (Report). Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- International Federation of Red Cross (September 28, 2018). "Saint Lucia Red Cross responds to tropical storm Kirk". ReiefWeb. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Banana industry on the mend after Tropical Storm Kirk". Government of Saint Lucia. October 15, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Poultry farmer loses 2000 chickens during storm". St. Lucia Times. September 30, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Miguel Mauricette (November 29, 2019). "Taiwanese Technical Mission contributes to agricultural security". Government of Saint Lucia. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Taiwan Technical Mission in St. Lucia assists the export of bananas to Europe through technical cooperation". International Cooperation and Development Fund. June 4, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Miguel Mauricette (November 28, 2018). "Tree crop planting program launched". Government of Saint Lucia. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Sullyvan Daphné (September 29, 2018). "Tempête Kirk : 2 000 foyers privés d'électricité, ce vendredi matin". RCI Martinique (in French). Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- "Le stade Pavilla de nouveau opérationnel". France-Antilles (in French). October 6, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Sullyvan Daphné (September 27, 2018). "Tempête Kirk : sirène déclenchée au Prêcheur à la suite d'un lahar". RCI Martinique (in French). Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Storm clouds gather over Macron's West Indies visit". Radio France Internationale. September 27, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Une saison cyclonique 2018 soutenue mais les Antilles préservées". France-Antilles (in French). December 3, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "Flash flood watch extended until 5:00 am tomorrow". The Jamaica Observer. October 2, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2020.