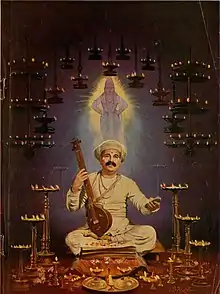

Tukaram

Sant Tukaram Maharaj (Marathi pronunciation: [t̪ukaːɾam]), also known as Tuka, Tukobaraya, Tukoba, was a Hindu, Marathi Saint of "Varkari sampradaya" in Dehu village, Maharashtra in the 17th century.[4][5] He was a bhakt of Lord Pandurang of Pandharpur.[3] He is best known for his devotional poetry called Abhanga, which are popular in Maharashtra, many of his poems deals with social reform.[5]

Sant Tukaram संत तुकाराम | |

|---|---|

Sant Tukaram Maharaj | |

| Personal | |

| Born | Tukaram Bolhoba Ambile Either 1598 or 1608[1][2] |

| Died | Either 1649 or 1650 in Dehu, Pune |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Known for | Abhanga (devotional poetry), Social Reformer -sant of Bhakti movement[3] |

| Other names | Tukoba, Tukobaraya |

| Dharma names | Sant Tukaram |

| Order | Varkari tradition |

| Religious career | |

| Literary works | Tukaram Gatha |

Biography

Early life

Tukaram was born in modern-day Maharashtra state of India. His complete name was Tukaram Bolhoba Ambile.[6][7] He was born in the year 1598 or 1608 in a village named Dehu, near Pune in Maharashtra, India.[2][7]

Tukaram was born to Kanakai and Bolhoba More and scholars consider his family to belong to the Kunbi caste.[8] Tukaram's family owned a retailing and money-lending business as well as were engaged in agriculture and trade.[3][7] His parents were devotees of Vithoba, an avatar of Hindu deity Vishnu (Vaishnavas). Both his parents died when Tukaram was a teenager.[7]

Tukaram's first wife was Rakhama Bai, and they had a son named Santu.[9] However, both his son and wife starved to death in the famine of 1630–1632.[3][10] The deaths and widespread poverty had a profound effect on Tukaram, who became contemplative, meditating on the hills of Sahyadri range (Western Ghats) and later wrote he "had discussions with my own self".[3][9] Tukaram married again, and his second wife was Avalai Jija Bai.[3][9]

Later life

He spent most of his later years in devotional worship, community kirtans (group prayers with singing) and composing Abhanga poetry.[3][9][11]

Tukaram pointed out the evil of wrongdoings of society, social system and Maharajs by his kiratans and abhangs.[12] He faced some opposition in society because of this. A man named Mambaji harassed him a lot, he was running a matha (religious seat) in Dehu and had some followers.[12] Initially Tukaram gave him the job of doing puja at his temple, but he was jealous of Tukaram by seeing Tukaram getting respect among the village people. He once hit Tukaram by thorn's stick.[12] He used foul language against Tukaram.[12] Later Mambaji also became admirer of Tukaram. He became his student.

Tukaram disappeared in 1649 or 1650.[2][13]

According to some scholars, Tukaram met Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj – a leader who founded the Maratha Empire;[9][14][15][16] Their continued interaction is the subject of legends.[16][17] Eleanor Zelliot states that Bhakti movement poets including Tukaram were influential in Shivaji's rise to power.[11]

Philosophy and practices

Vedanta

.jpg.webp)

In his work of Abhangas, Tukarama repeatedly refers to four other persons who had a primary influence on his spiritual development, namely the earlier Bhakti Sants Namdev, Dnyaneshwar, Kabir and Eknath.[18] Early 20th-century scholars on Tukaram considered his teachings to be Vedanta-based but lacking a systematic theme. JF Edwards wrote,

Tukaram is never systematic in his psychology, his theology, or his theodicy. He oscillates between a Dvaitist [Vedanta] and an Advaitist view of God and the world, leaning now to a pantheistic scheme of things, now to a distinctly Providential, and he does not harmonize them. He says little about cosmogony, and according to him, God realizes Himself in the devotion of His worshippers. Likewise, faith is essential to their realization of Him: 'It is our faith that makes thee a god', he says boldly to his Vithoba.[19]

Late 20th-century scholarship of Tukaram, and translations of his Abhanga poem, affirm his pantheistic Vedantic view.[20] Tukaram's Abhanga 2877, as translated by Shri Gurudev Ranade of Nimbal states, for example, "The Vedanta has said that the whole universe is filled by God. All sciences have proclaimed that God has filled the whole world. The Puranas have unmistakably taught the universal immanence of God. The sants have told us that the world is filled by God. Tuka indeed is playing in the world uncontaminated by it like the Sun which stands absolutely transcendent".[20]

Scholars note the often discussed controversy, particularly among Marathi people, whether Tukaram subscribed to the monistic Vedanta philosophy of Adi Shankara.[21][22] Bhandarkar notes that Abhanga 300, 1992 and 2482 attributed to Tukaram are in style and philosophy of Adi Shankara:[21]

When salt is dissolved in water, what is it that remains distinct?

I have thus become one in joy with thee [Vithoba, God] and have lost myself in thee.

When fire and camphor are brought together, is there any black remnant left?

Tuka says, thou and I are one light.— Tukaram Gatha, 2482, Translated by RG Bhandarkar[21]

However, scholars also note that other Abhangas attributed to Tukaram criticize monism, and favor dualistic Vedanta philosophy of the Indian philosophers Madhvacharya and Ramanuja.[21] In Abhanga 1471, according to Bhandarkar's translation, Tukaram says, "When monism is expounded without faith and love, the expounder as well as the hearer are troubled and afflicted. He who calls himself Brahma and goes on in his usual way, should not be spoken to and is a buffoon. The shameless one who speaks heresy in opposition to the Vedas is an object of scorn among holy men."[21]

The controversy about Tukaram's true philosophical positions has been complicated by questions of authenticity of poems attributed to him, discovery of manuscripts with vastly different number of his Abhang poems, and that Tukaram did not write the poems himself, they were written down much later, by others from memory.[23]

Tukaram denounced mechanical rites, rituals, sacrifices, vows and instead encouraged direct form of bhakti (devotion).[21][24]

Kirtan

Tukaram encouraged kirtan as a music imbued, community-oriented group singing and dancing form of bhakti.[5] He considered kirtan not just a means to learn about Bhakti, but Bhakti itself.[5] The greatest merit in kirtan, according to Tukaram, is it being not only a spiritual path for the devotee, it helps create a spiritual path for others.[25]

Social reforms

Tukaram accepted disciples and devotees without discriminating on the basis of gender. One of his celebrated devotees was Bahina Bai, a Brahmin woman, who faced anger and abuse of her husband when she chose Bhakti marga and Tukaram as her guru.[26]

Tukaram taught, states Ranade,[27] that "pride of caste never made any man holy", "the Vedas and Shastras have said that for the service of God, castes do not matter", "castes do not matter, it is God's name that matters", and "an outcast who loves the Name of God is verily a Brahmin; in him have tranquility, forbearance, compassion and courage made their home".[27] However, early 20th century scholars questioned whether Tukaram himself observed caste when his daughters from his second wife married men of their own caste.[28] Fraser and Edwards, in their 1921 review of Tukaram, stated that this is not necessarily so, because people in the West too generally prefer relatives to marry those of their own economic and social strata.[28]

David Lorenzen states that the acceptance, efforts and reform role of Tukaram in the Varakari-sampraday follows the diverse caste and gender distributions found in Bhakti movements across India.[29] Tukaram, of Shudra varna, was one of the nine non-Brahmins, of the twenty one considered sant in Varakari-sampraday tradition.[29] The rest include ten Brahmins and two whose caste origins are unknown.[29] Of the twenty one, four women are celebrated as sant, born in two Brahmin and two non-Brahmin families. Tukaram's effort at social reforms within Varakari-sampraday must be viewed in this historical context and as part of the overall movement, states Lorenzen.[29]

Literary works

Tukaram composed Abhanga poetry, a Marathi genre of literature which is metrical (traditionally the ovi meter), simple, direct, and it fuses folk stories with deeper spiritual themes.

Tukaram's work is known for informal verses of rapturous abandon in folksy style, composed in vernacular language, in contrast to his predecessors such as Dnyandeva or Namdev known for combining similar depth of thought with a grace of style.[31]

In one of his poems, Tukaram self-effacingly described himself as a "fool, confused, lost, liking solitude because I am wearied of the world, worshipping Vitthal (Vishnu) just like my ancestors were doing but I lack their faith and devotion, and there is nothing holy about me".[32]

Tukaram Gatha is a Marathi language compilation of his works, likely composed between 1632 and 1650.[31] Also called Abhanga Gatha, the Indian tradition believes it includes some 4,500 abhangas. The poems considered authentic cover a wide range of human emotions and life experiences, some autobiographical, and places them in a spiritual context.[31] He includes a discussion about the conflict between Pravritti – having passion for life, family, business, and Nivritti – the desire to renounce, leave everything behind for individual liberation, moksha.[31]

Ranade states there are four major collations of Tukaram's Abhanga Gathas.[33]

Authenticity

Numerous inconsistent manuscripts of Tukaram Gatha are known, and scholars doubt that most of the poems attributed to Tukaram are authentic.[31] Of all manuscripts so far discovered, four are most studied and labelled as: the Dehu MS, the Kadusa MS, the Talegeon MS and the Pandharpur MS.[34] Of these, the Dehu MS is most referred to because Indian tradition asserts that it is based on the writing of Tukaram's son Mahadeva, but there is no historical evidence that this is true.[34]

The first compilation of Tukaram poems was published, in modern format, by Indu Prakash publishers in 1869, subsidized by the British colonial government's Bombay Presidency.[34] The 1869 edition noted, "some of the [as received] manuscripts on which the compilation relied, had been 'corrected', 'further corrected' and 'arranged'."[34] This doctoring and rewriting over about 200 years, after Tukaram's death, has raised questions whether the modern compilation of Tukaram's poems faithfully represents what Tukaram actually thought and said, and the historicity of the document. The known manuscripts are jumbled, randomly scattered collections, without chronological sequence, and each contains some poems that are not found in all other known manuscripts.[35]

Books and translations

The 18th-century biographer Mahipati, in his four volume compilation of the lives of many Bhakti movement sants, included Tukaram. Mahipati's treatise has been translated by Justin Abbott.[11][36]

A translation of about 3,700 poems from Tukaram Gatha in English was published, in three volumes, between 1909 and 1915, by Fraser and Marathe.[37] In 1922, Fraser and Edwards published his biography and religious ideas incorporating some translations of Tukaram's poems,[38] and included a comparison of Tukaram's philosophy and theology with those of Christianity.[39] Deleury, in 1956, published a metric French translation of a selection of Tukaram's poem along with an introduction to the religious heritage of Tukaram (Deleury spells him as Toukaram).[40]

Arun Kolatkar published, in 1966, six volumes of avant-garde translations of Tukaram poems.[11] Ranade has published a critical biography and some selected translation.[41]

Dilip Chitre translated writings of Sant Tukaram into English in the book titled Says Tuka for which he was awarded the Sahitya Akademi award in 1994.[35] A selection of poems of Tukaram has been translated and published by Daniel Ladinsky.[42]

Chandrakant Kaluram Mhatre has translated selected poems of Tukaram, published as One Hundred Poems of Tukaram.[43]

Legacy

Maharashtra society

Tukaram's abhangs are very popular in Maharashtra. It became part of the culture of the state. Varkaris, poets and peoples study his poems. His poems are popular in rural Maharashtra and their popularity is increasing.[44] Tukaram was a devotee of Vithoba (Vitthala), an avatar of God Vishnu, synchronous with Krishna but with regional style and features.[11] Tukaram's literary works, along with those of sants Dnyandev, Namdev and Eknath, states Mohan Lal, are credited to have propelled Varkari tradition into pan-Indian Bhakti literature.[45]

According to Richard Eaton, from early 14th-century when Maharashtra region came under the rule of the Delhi Sultanate, down to the 17th-century, the legacy of Tukaram and his poet-predecessors, "gave voice to a deep-rooted collective identity among Marathi-speakers".[46] Dilip Chitre summarizes the legacy of Tukaram and Bhakti movement sants, during this period of Hindu-Muslim wars, as transforming "language of shared religion, and religion a shared language. It is they who helped to bind the Marathas together against the Mughals on the basis not of any religious ideology but of a territorial cultural identity".[47]

Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi, in early 20th century, while under arrest in Yerwada Central Jail by the British colonial government for his non-violent movement, read and translated Tukaram's poetry along with Upanishads, Bhagavad Gita and poems by other Bhakti movement poet-saints.[48]

Saintliness is not to be purchased in shops,

nor is it to be had for wandering, nor in cupboards, nor in deserts, nor in forests.

It is not obtainable for a heap of riches. It is not in the heavens above, nor in the entrails of the earth below.

Tuka says: It is a life's bargain, and if you will not give your life to possess it, better be silent.

The essence of the endless Vedas is this: Seek the shelter of God and repeat His name with all thy heart.

The result of the cogitations of all the Shastras is also the same.

Tuka says: The burden of the eighteen Puranas is also identical.

Merit consists in doing good to others, sin in doing harm to others. There is no other pair comparable to this.

Truth is the only freedom; untruth is bondage, there is no secret like this.

God's name on one's lips is itself salvation, disregarding the name is perdition.

Companionship of the good is the only heaven, indifference is hell.

Tuka says: It is thus clear what is good and what is injurious, let people choose what they will.

Sant Tukaram also had a profound influence on K. B. Hedgewar as the former's quotes often found their way on the latter's letterhead. One such letter dated April 6, 1940 bore the quote "Daya tiche nanwa bhutanche palan, aanik nirdalan kantkache", meaning compassion is not only the welfare of all living beings, but also includes protecting them from harm's way.[49]

Places associated with Tukaram

Places associated with Tukaram in Dehu that exist today are:

- Tukaram Maharaj Janm Sthan Temple, Dehu – place where Tukaramji was born, around which a temple was built later

- Sant Tukaram Vaikunthstan Temple, Dehu – from where Tukaramji ascended to Vaikuntha (Abode of God) in his mortal form; there is a beautiful ghat behind this temple along the Indrayani river

- Sant Tukaram Maharaj Gatha Mandir, Dehu – modern structure; massive building housing a big statue of Tukaram; In the Gatha temple, about 4,000 abhangs (verses) created by Tukaram maharaj were carved on the walls.[50]

Movies and popular culture

A number of Indian films have been made about the saint in different languages. These include:

- Tukaram (1921) silent film by Shinde.

- Sant Tukaram (1921) silent film by Kalanidhi Pictures.

- Sant Tukaram (1936) – this movie on Tukaram was screened open-air for a year, to packed audiences in Mumbai, and numerous rural people would walk very long distances to see it.[51]

- Thukkaram (1938) in Tamil by B. N. Rao.

- Santha Thukaram (1963) in Kannada

- Sant Tukaram (1965) in Hindi

- Bhakta Tukaram (1973) in Telugu

- Tukaram (2012) in Marathi

Tukaram's life was the subject of the 68th issue of Amar Chitra Katha, India's largest comic book series.[52]

Balbharti has included a poem of Tukaram in a Marathi school textbook

The government of India had issued a 100 rupee Silver commemorative coin in 2002.[53]

See also

- Bhakti movement

- Pandharpur Wari – the largest annual pilgrimage in Maharashtra that includes a ceremonial Palkhi of Tukaram

- Vitthal Temple, Pandharpur

- Sant Dnyaneshwar

References

- Ranade 1994, pp. 3–7.

- Tulpule & Shelke 1992, p. 148.

- Mohan Lal (1993), Encyclopedia of Indian Literature: Sasay to Zorgot, Sahitya Akademi, South Asia Books, ISBN 978-9993154228, pages 4403-4404

- Maxine Bernsten (1988), The Experience of Hinduism: Essays on Religion in Maharashtra, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0887066627, pages 248-249

- Anna Schultz (2012), Singing a Hindu Nation: Marathi Devotional Performance and Nationalism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199730834, page 62

- Ranade 1994, pp. 1–7.

- Richard M. Eaton (2005), A Social History of the Deccan, 1300–1761: Eight bji kg b Indian Lives, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521716277, pages 129-130

- Palgrave Macmillan, ed. (2002). Challenging Subjects: Critical Psychology for a New Millennium. p. 119.

Tukaram thanks God for his having been born a kunbi (a farming caste) and not, by implication, as every commentator agrees, a brahmin

- Ranade 1994, p. 7-9.

- Tulpule & Shelke 1992, pp. 150–152.

- Eleanor Zelliot (1976), Hinduism: New Essays in the History of Religions (Editor: Bardwell L Smith), Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004044951, pages 154-156

- "बहु फार विटंबिले." Loksatta (in Marathi). 26 June 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- Ranade 1994, p. 1-2.

- Stewart Gordon (1993). The Marathas 1600–1818. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-521-26883-7.

- Kaushik Roy (2015). Warfare in Pre-British India – 1500BCE to 1740CE. Routledge. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-1-317-58692-0.

- Justin Edwards Abbott (2000), Life of Tukaram, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120801707, page 320

- Tulpule & Shelke 1992, pp. 158–163.

- Ranade 1994, pp. 10–12.

- JF Edwards (1921), Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics: Suffering-Zwingli, Volume 12, Editors: James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie and Louis Herbert Gray, New York: Charles Scribner, Reprinted in 2000 as ISBN 978-0567065124, page 468

- Ranade 1994, p. 192-197.

- R G Bhandarkar (2014), Vaisnavism, Saivism and Minor Religious Systems, Routledge, ISBN 978-1138821064, pages 98-99

- Charles Eliot (1998), Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch, Volume 2, Routledge, ISBN 978-0700706792, page 258, Quote: "Maratha critics have discussed whether Tukaram followed the monistic philosophy of Sankara or more, and it must be confessed that his utterances are contradictory."

- The Life and Teaching of Tukaram J Nelson Fraser, and JF Edwards, Probsthain, Christian Literature Society, pages 119-123, 218-221

- David Lorenzen (2006), Who Invented Hinduism: Essays on Religion in History, Yoda Press, ISBN 978-8190227261, page 130

- Anna Schultz (2012), Singing a Hindu Nation: Marathi Devotional Performance and Nationalism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199730834, pages 25-28

- Feldhaus 1982, pp. 591-604.

- Ranade 1994, p. 154-156.

- The Life and Teaching of Tukaram J Nelson Fraser, and JF Edwards, Probsthain, Christian Literature Society, pages 163, 54-55

- David Lorenzen (2006), Who Invented Hinduism: Essays on Religion in History, Yoda Press, ISBN 978-8190227261, pages 127-128

- Gatha Temple, National Geographic (2014)

- Mohan Lal (1993), Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Sasay to Zorgot, Sahitya Akademi, South Asia Books, ISBN 978-9993154228, pages 4404-4405

- Tulpule & Shelke 1992, pp. 149–150.

- Ranade 1994, pp. 19–22.

- The Life and Teaching of Tukaram J Nelson Fraser, and JF Edwards, Probsthain, Christian Literature Society, pages 119-124

- Chitre 1991, p. .

- Justin Abbott (2000), Tukaram: The Poet-Saints of Maharashtra, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120801707

- J Nelson Fraser and KB Marathe, The Poems of Tukaram, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120808515

- The Life and Teaching of Tukaram J Nelson Fraser, and JF Edwards, Probsthain, Christian Literature Society

- The Life and Teaching of Tukaram J Nelson Fraser, and JF Edwards, Probsthain, Christian Literature Society, pages 274-278, Appendix II & III

- Guy A Deleury (1956), Psaumes dy Pelerin: Toukaram, Paris: Gallimard, ISBN 978-2070717897, pages 9-34

- Ranade 1994, p. .

- Daniel Ladinsky (2002), Love Poems from God, Penguin, ISBN 978-0142196120, pages 331-352

- Chandrakant Kaluram Mhatre, One Hundred Poems of Tukaram, Createspace, ISBN 978-1512071252

- Nathe, Sanjay (2017). Kantrati Gramsevak. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-93-85369-97-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - Mohan Lal (1993), Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Sasay to Zorgot, Sahitya Akademi, South Asia Books, ISBN 978-9993154228, page 4403

- Richard M. Eaton (2005), A Social History of the Deccan, 1300–1761: Eight Indian Lives, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521716277, pages 138-141

- Dilip Chitre (1991), Says Tuka: Selected Poetry of Tukaram, Penguin, ISBN 978-0140445978, pages xvi-xvii

- MK Gandhi (1930), Songs from prison: translations of Indian Lyrics made in Jail, (Adapted and formatted by John Hoyland, 1934), New York : Macmillan, OCLC 219708795

- Sunil Ambekar (2019). The RSS: roadmaps for the 21st century. New Delhi: Rupa. p. 19. ISBN 9789353336851.

- "Gatha Mandir".

- Chowdhry 2000, p. 155.

- Babb & Wadley 1998, p. 131.

- 100 rupees coin of 2002 - Sant Tukaram (video). Coins & Currencies. 2 March 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

Works cited

- Babb, Lawrence A.; Wadley, Susan S. (31 May 1998). Media and the Transformation of Religion in South Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-1453-0.

- Chowdhry, Prem (2000). Colonial India and the Making of Empire Cinema: Image, Ideology and Identity. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5792-2.

- Chitre, Dilip (1991). Says Tuka: Selected Poetry of Tukaram. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044597-8.

- Feldhaus, Anne (1982). "BahināBāī: Wife and Saint". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. L (4): 591–604. doi:10.1093/jaarel/l.4.591. ISSN 0002-7189.

- Tulpule, S. G.; Shelke, Christopher (25 September 1992). McGregor, R. S. (ed.). Devotional Literature in South Asia: Current Research, 1985-1988. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-41311-4.

- Ranade, Ramchandra D. (1994). Tukaram. New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-2092-2.

General references

- Ayyappapanicker, K.; Akademi, Sahitya (1997). Medieval Indian Literature: An Anthology. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-260-0365-0.

- "Tryambak Shankar Shejwalkar Nivadak Lekhsangrah" by T S Shejwalkar (collection- H V Mote, Introduction- G D Khanolkar)

Further reading

- John Hoyland (1932), An Indian Peasant Mystic: Translations from Tukaram, London: Allenson, OCLC 504680225

- Wilbur Deming (1932), Selections from Tukaram, Christian Literature Society, OCLC 1922126

- Prabhakar Machwe (1977), Tukaram's Poems, United Writer, OCLC 4497514

- Dilip Chitre (1970), The Bhakta as a Poet: Six Examples from Tukaram's Poetry, Delos: A Journal on and of Translation, Vol. 4, pages 132-136

- Fraser, James Nelson; Rev. JF Edwards (1922). The Life and Teaching of Tukārām. The Christian Literature Society for India, Madras.

- Fraser and Marathe (1915), The Poems of Tukaram, 3 vols, Christian Literature Society OCLC 504680214, Reprinted in 1981 by Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120808515

External links

- Works by or about Tukaram at Internet Archive

- Collected works of Tukaram in Devnagari

- Sant Tukaram Gatha at Internet Archive

- Images, Biography: Tukaram Ram Bapat (2002), Tukaram Online, 14 Indian and 8 foreign languages

- What I Want to Say, Tukaram, Mona van Duyn (1965), Poetry, Vol. 107, No. 2, pages 102-104

- Twenty five poems, Tukaram Prabhakar Machwe (1968), Mahfil, Vol. 5, No. 1/2, pages 61–69

- Translations from Tukaram and other saint-poets, Awad Kolatkar (1982), Journal of South Asian Literature, Vol. 17, No. 1, pages 111-114