Dong Qichang

Dong Qichang (Chinese: 董其昌; pinyin: Dǒng Qíchāng; Wade–Giles: Tung Ch'i-ch'ang; courtesy name Xuanzai (玄宰); 1555–1636), was a Chinese art theorist, calligrapher, painter, and politician of the later period of the Ming dynasty.

Life as a scholar and calligrapher

Dong Qichang was a native of Hua Ting (located in modern-day Shanghai), the son of a teacher and somewhat precocious as a child. At 12 he passed the prefectural Civil service entrance examination and won a coveted spot at the prefectural Government school. He first took the imperial civil service exam at seventeen, but placed second to a cousin because his calligraphy was clumsy. This led him to train until he became a noted calligrapher. Once this occurred he rose up the ranks of the imperial service passing the highest level at the age of 35. He rose to an official position with the Ministry of Rites.[1]

.jpg.webp)

His positions in the bureaucracy were not without controversy. In 1605 he was giving the exam when the candidates demonstrated against him causing his temporary retirement. In other cases he insulted and beat women who came to his home with grievances. That led to his house being burned down by an angry mob. He also had the tense relations with the eunuchs common to the scholar bureaucracy. Dong's tomb in Songjiang District was vandalized during the Cultural Revolution, and his body dressed in official Ming court robes, was desecrated by Red Guards.

Painter

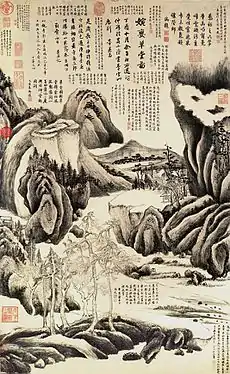

His work favored expression over formal likeness. He also avoided anything he deemed to be slick or sentimental. This led him to create landscapes with intentionally distorted spatial features. Still his work was in no way abstract as it took elements from earlier Yuan masters. His views on expression had importance to later "individualist" painters.

Art theory

In his art theoretical writings, Dong developed the theory that Chinese painting could be divided into two schools, the northern school characterized by fine lines and colors and the southern school noted for its quick calligraphic strokes. These names are misleading as they refer to Northern and Southern schools of Chan Buddhism thought rather than geographic areas. Hence a Northern painter could be geographically from the south and a Southern painter geographically from the north. In any event he strongly favored the Southern school and dismissed the Northern school as superficial or merely decorative.

His ideal of Southern school painting was one where the artist forms a new style of individualistic painting by building on and transforming the style of traditional masters. This was to correspond with sudden enlightenment, as favored by Southern Chan Buddhism. He was a great admirer of Mi Fu and Ni Zan.[2] By relating to the ancient masters' style, artists are to create a place for themselves within the tradition, not by mere imitation, but by extending and even surpassing the art of the past. Dong's theories, combining veneration of past masters with a creative forward looking spark, would be very influential on Qing dynasty artists[3] as well as collectors, "especially some of the newly rich collectors of Sungchiang, Huichou in Southern Anhui, Yangchou, and other places where wealth was concentrated in this period".[4] Together with other early self-appointed arbiters of taste known as the Nine Friends, he helped determine which painters were to be considered collectible (or not). As Cahill points out, such men were the forerunners of today's art historians. His classifications were quite perceptive and he is credited with being "the first art historian to do more than list and grade artists."[5]

Gallery

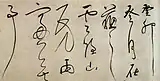

Dong Qichang, calligraphy of cursive and semi-cursive style, 1603. Tokyo National Museum.

Dong Qichang, calligraphy of cursive and semi-cursive style, 1603. Tokyo National Museum. Dong Qichang, The Qingbian Mountains in the Manner of Tung Yuan, dated 1617. Cleveland Museum of Art.

Dong Qichang, The Qingbian Mountains in the Manner of Tung Yuan, dated 1617. Cleveland Museum of Art. Dong Qichang, Wanluan Thatched Hall (婉娈草堂图), 1597. Private collection, Taipei.

Dong Qichang, Wanluan Thatched Hall (婉娈草堂图), 1597. Private collection, Taipei. Dong Qichang, Eight Views of Autumn Moods, dated 1620. Album of eight leaves, leaf one. Shanghai Museum.

Dong Qichang, Eight Views of Autumn Moods, dated 1620. Album of eight leaves, leaf one. Shanghai Museum. Dong Qichang, Eight Views of Autumn Moods, dated 1620. Album of eight leaves, leaf four. Shanghai Museum.

Dong Qichang, Eight Views of Autumn Moods, dated 1620. Album of eight leaves, leaf four. Shanghai Museum. Dong Qichang, Eight Views of Autumn Moods, dated 1620. Album of eight leaves, leaf five. Shanghai Museum.

Dong Qichang, Eight Views of Autumn Moods, dated 1620. Album of eight leaves, leaf five. Shanghai Museum. Dong Qichang, Eight Views of Autumn Moods, dated 1620. Album of eight leaves, leaf seven. Shanghai Museum.

Dong Qichang, Eight Views of Autumn Moods, dated 1620. Album of eight leaves, leaf seven. Shanghai Museum.._Album_leaf.1621-24_Nelson-Atkuns_Museum.jpg.webp) Dong Qichang, Landscapes in the Manner of Old Masters, dated 1621-24. Album of ten leaves, leaf two. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Dong Qichang, Landscapes in the Manner of Old Masters, dated 1621-24. Album of ten leaves, leaf two. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Dong Qichang, Autumn Landscape. Private collection.

Dong Qichang, Autumn Landscape. Private collection. Seeking Ancient in Fengjing (葑泾访古图), ink on paper, height 80 cm, width 29.8 cm, National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Seeking Ancient in Fengjing (葑泾访古图), ink on paper, height 80 cm, width 29.8 cm, National Palace Museum, Taipei. Dong Qichang, Tree in Summer with the Shadow, National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Dong Qichang, Tree in Summer with the Shadow, National Palace Museum, Taipei.

References

- Lawrence Gowing, ed., Biographical Encyclopedia of Artists, v.4 (Facts on File, 2005): 682.

- "Landscapes after Old Masters". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2023-01-11.

- Edmund Capon and Mae Anna Pang, Chinese Paintings of the Ming and Qing Dynasties Catalogue 1981, International Cultural Corporation of Australia Ltd.

- James Cahill, The Painter's Practice: How Artists Lived and Worked in Traditional China. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994, p. 11

- Lawrence Gowing, ed., Biographical Encyclopedia of Artists, v.4 (Facts on File, 2005): 683.

Sources

- Bryant, Shelly, The Classical Gardens of Shanghai. Hong Kong University Press, 2016. p. 26-40.

- Hummel, Arthur W. Sr., ed. (1943). . Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office.

- Rhonda and Jeffrey Cooper, Masterpieces of Chinese Art (pages 106 and 109), Todtri Productions, 1997. ISBN 1-57717-060-1

- Xiao, Yanyi, "Dong Qichang". Encyclopedia of China, 1st ed.

External links

- Calligraphy Gallery of Dong Qichang at China Online Museum

- Painting Gallery of Dong Qichang at China Online Museum

- Calligraphy by Dong Qichang at Chinapage

- The Biography of Dong Qichang and his Achievements in Calligraphy and Painting at MildChina

- Paintings at the site of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston's online collection

- Landscapes Clear and Radiant: The Art of Wang Hui (1632–1717), catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- WWU article on Dong Qichang