Two Trains Running

Two Trains Running is a 1990 play by American playwright August Wilson, the sixth in his ten-part series The Pittsburgh Cycle. The play takes place in 1968 in the Hill District, an African-American neighborhood in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It explores the social and psychological manifestations of changing attitudes toward race from the perspective of its urban Black characters. The play premiered on Broadway in 1992 and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

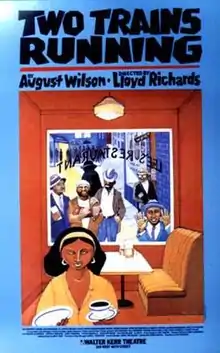

| Two Trains Running | |

|---|---|

Broadway production poster | |

| Written by | August Wilson |

| Date premiered | 1990 |

| Place premiered | Yale Repertory Theatre New Haven, Connecticut |

| Original language | English |

| Series | The Pittsburgh Cycle |

| Subject | The uncertain future promised by the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s |

| Genre | Drama |

| Setting | the Hill District of Pittsburgh, 1969 |

Synopsis

In 1968 amidst the civil rights movement, Memphis Lee's restaurant is set to be demolished by the city. While he fights to be paid a fair price for his property, his employees and regulars search for work, love, and justice as their neighborhood changes around them.

Cast

- Memphis, a migrant from the Deep South – owner and operator of a restaurant that has been a community center but has declined in business

- Risa – the only woman in the play, she works at the restaurant. She and Sterling begin a relationship.

- Sterling – young man from the neighborhood who was recently released from prison

- Holloway – an elder of this community, he is described as "the seer and the knower"[1]

- Wolf – a numbers runner, small-time gambler, and "town crier"[1]

- West – funeral director and longest-standing business owner in the community[1]

- Hambone – he repeats one phrase in his search for justice

Productions

Two Trains Running was first performed by the Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven, Connecticut in March 1990.[2] Productions soon followed at the Huntington Theatre (Boston, Massachusetts), Seattle Repertory Theatre (Seattle, Washington), and Old Globe Theatre (San Diego, California).[3]

The play premiered on Broadway at the Walter Kerr Theatre on April 13, 1992. It closed there on August 30, 1992 after 160 performances and 7 previews. Directed by Lloyd Richards, the cast featured Roscoe Lee Browne as Holloway, Anthony Chisholm as Wolf, Laurence Fishburne as Sterling, Chuck Patterson as West, and Cynthia Martells as Risa.[4]

Historical context

African-American migration

Seeking to escape from poverty, racism, and segregation imposed by "Jim Crow" laws in the South, more than 6 million Black Americans migrated to northern, midwestern and western industrial cities during the early and mid-20th century, a movement ending about 1970. Most of these migrants had worked in agriculture in the former Confederate slave states, and few were well acquainted with urban life. Broadly speaking, blacks who moved north could expect higher wages in industrial jobs, better educational opportunities, and greater potential for social advancement than possible in the South. They were also able to vote.

While racism in the North was arguably less violent and overt than in the South, it was nonetheless present. Though lynching was much more rare and de jure segregation did not exist in the North, negative attitudes towards blacks prevailed among many white citizens. Blacks were forced into de facto segregated neighborhoods - the newest arrivals having to take older housing. Suburban development, especially after World War II, attracted people who wanted newer housing and could afford to move. These were more white than black initially, although the black middle class also began to leave the inner city. At the same time, industrial restructuring caused the loss of many jobs in such cities as Pittsburgh. Poorer and less educated blacks were left in inner city neighborhoods, with fewer resources.

Because of the loss of working-class jobs, these overwhelmingly Black neighborhoods began to be areas of concentrated high poverty and associated crime rates. Yet these neighborhoods also simmered with their people's hopes of economic, social, and political advancement. As such, they served as fertile soil for the Civil Rights Movement and Black Power movement. Two Trains Running is set in such a neighborhood.

The Hill District in the 1960s

The play is set in 1968 at a restaurant at 1621 Wylie Avenue, in Pittsburgh's Hill District, an African-American neighborhood. In the 1940s and 1950s, the Hill District was one of the most prosperous, culturally active Black neighborhoods in the United States. Under pressure of de facto segregation, industrial restructuring and suburbanization in the 1960s, however, the neighborhood suffered a sharp economic decline.[5]

Business owner Memphis recounts how his restaurant, which now has few patrons, used to be packed with customers. It has long been a community center, and regulars still come in. He notes how many once-bustling small businesses have since closed down.

Throughout the 1960s, Pittsburgh's Urban Redevelopment Authority seized land in the area as part of the movement known generally as urban renewal. They planned to get rid of aging buildings in order to build civil structures and public housing. Countless buildings were destroyed to make way for the Civic Arena and other projects.[5] This effort displaced thousands of people, disrupting the remnants of The Hill community.

Memphis's building is one targeted to be seized by the city (presumably by the URA). He is nervous about the price he will receive for it. Speaking of the eminent domain clause in his deed, he says "They don't know I got a clause of my own... They can carry me out feet first... but my clause say... they got to meet my price!" Like Hambone's "He gonna give me my ham", this indignant insistence represents an unyielding demand for dignity and respect from those who have historically been denied it.

Urban unrest and the Black Power movement

Throughout Act Two of the play, Sterling (a young man from the neighborhood recently released from the state penitentiary) eagerly awaits a political rally, for which he tries to generate interest at the restaurant. Though he makes it clear that the rally involves racial justice, he does not specify its exact motivations or political aims. Memphis reacts with scorn when Sterling posts a flyer for the event, but he never makes it clear exactly why he is so uncomfortable with it.

The rally is set within the context of riots in Pittsburgh in the late 1960s. After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, a wave of riots from grief and despair erupted in urban, black areas of the United States. Though the riots in Pittsburgh were not as devastating as those in Washington, D.C., and Chicago that year, they resulted in extensive property damage to struggling black areas, and escalated tensions of their residents with the city police, who were still mostly white.

Memphis's scorn also reflects a broader generational conflict on the topic of resistance that came to a head in the late 1960s. Many older, southern-born blacks like Memphis had learned to survive by not stirring up trouble with the white establishment. Those in the younger generation, such as Sterling, who had often grown up in the North, viewed this attitude as implicit submission—a remnant of slave mentality worthy of contempt.

This shift in attitude was expressed in the evolution of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1960, the movement relied primarily on legal action and political lobbying by organizations such as the NAACP, which conducted litigation to challenge disenfranchisement and segregation, as well as defend suspects in egregious cases of apparently innocent people being charged for crimes. Over the next few years, however, nonviolent mass action emerged as the primary tactic in the South, organized through the strong church communities and led by such ministers as Martin Luther King, Jr and others of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. In Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina and other states, blacks conducted boycotts and sit-ins of segregated buses and businesses, seeking change; they also organized voter education and protests. They sought to end segregation in public places and retail establishments, to gain work opportunities, and to end the disenfranchisement of most black voters in the South. The 1963 March on Washington was an expression of widespread grassroots organizing across the South.

Federal civil rights legislation and the Voting Rights Act were passed in 1964 and 1965, but by the later 1960s, many younger members of the movement questioned the idea of nonviolence. They believed that change and equity were not happening quickly enough. For example, in 1966, Stokely Carmichael became leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Carmichael believed that true liberation for black people required direct seizure of power, and building their own businesses and networks, rather than appeal to white power structures. He dismissed all white members of SNCC, saying they should work to change their own people. The organization effectively became part of the Black Power movement, and over the next few years SNCC dissolved. Many of its leaders (including Carmichael) joined the more radical Black Panther Party.

Black women in the 1960s

Though Risa has relatively few lines, she is one of the most powerful characters in Two Trains Running. She has defined herself by actions to set herself apart. Despite his own personal struggles with oppression, Memphis does not seem to recognize how poorly he treats Risa. He never thanks her or shows appreciation for her work, and he constantly meddles in her affairs as if she could not manage without him.

While Holloway is polite to Risa, he does nothing to defend her from Memphis's persistent criticism. He has much to say about the topic of racial injustice, but he seems oblivious or apathetic to the gender injustice that occurs before his eyes at the restaurant.

When Sterling invites Risa to the rally, she shows little interest. Though she does not say so explicitly, it appears she feels alienated from the Civil Rights and Black Power movements.

These interactions express the exclusion of women from most positions of official power in the civil rights movement. As one author writes:

The movement, though ostensibly for the liberation of the black race, was in word and deed for the liberation of the black male. Race was extremely sexualized in the rhetoric of the movement. Freedom was equated with manhood and the freedom of blacks with the redemption of black masculinity.[6]

Awards and nominations

- Awards

- 1991 American Theatre Critics Association New Play Award, for the best new play not yet produced in New York[7]

- 1992 Tony Award, Best Featured Actor in a Play (Laurence Fishburne)

- 1992 Drama Desk Award Outstanding Featured Actor in a Play (Fishburne)

- 2007 Lucille Lortel Award for Outstanding Revival

- Nominations

- 1992 Pulitzer Prize for Drama[8]

- 1992 Tony Award for Best Play [4]

- 1992 Tony Award Best Featured Actor in a Play (Roscoe Lee Browne)

- 1992 Tony Award Best Featured Actress in a Play (Cynthia Martells)

- 2007 Audelco Award for Dramatic Production of the Year

References

- Koking, Natalie (18 March 2019). "The Characters of August Wilson's TWO TRAINS RUNNING". Cincinnati Playhouse Blog. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- Rizzo, Frank. "'Trains Likely To Be Rep's Last Ride To Broadway" Hartford Courant, April 13, 1992

- Churnin, Nancy. "A Director With a New Direction : Stage: Lloyd Richards, at the Old Globe for 'Two Trains,' will abandon some tasks to concentrate on what matters most to him: directing, teaching and searching out new talent." Los Angeles Times, March 15, 1991

- "'Two Trains Running" Broadway", playbill.com, 2012, accessed April 12, 2016

- "Study Guide, The Hill District, p. 4" Archived 2012-08-23 at the Wayback Machine theoldglobe.org, accessed April 12, 2016

- "Black Women in the Black Liberation Movement", in But Some of Us Are Brave: A History of Black Feminism in the United States, mit.edu, accessed April 12, 2016

- "Home".

- "Pulitzer Prize, Drama" pulitzer.org, accessed April 12, 2016

- Wilson, August (1992). Two Trains Running (First ed.). New York: Plume. ISBN 0-452-26929-6.