Coal mining in the United Kingdom

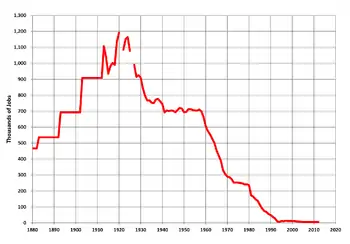

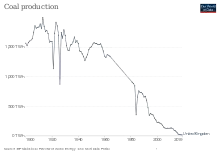

Coal mining in the United Kingdom dates back to Roman times and occurred in many different parts of the country. Britain's coalfields are associated with Northumberland and Durham, North and South Wales, Yorkshire, the Scottish Central Belt, Lancashire, Cumbria, the East and West Midlands and Kent. After 1972, coal mining quickly collapsed and had practically disappeared by the 21st century.[1] The consumption of coal – mostly for electricity – fell from 157 million tonnes in 1970 to 18 million tonnes in 2016, of which 77% (14 million tonnes) was imported from Colombia, Russia, and the United States.[2] Employment in coal mines fell from a peak of 1,191,000 in 1920 to 695,000 in 1956, 247,000 in 1976, 44,000 in 1993, and to 2,000 in 2015.[3]

Almost all onshore coal resources in the UK occur in rocks of the Carboniferous period, some of which extend under the North Sea. Bituminous coal is present in most of Britain's coalfields and is 86% to 88% carbon. In Northern Ireland, there are extensive deposits of lignite which is less energy-dense based on oxidation (combustion) at ordinary combustion temperatures (i.e. for the oxidation of carbon – see fossil fuels).[4]

The last deep coal mine in the UK closed on 18 December 2015. Twenty-six open cast mines still remained in operation at the end of 2015.[5] Banks Mining said in 2018 they planned to start mining a new site in County Durham[6] but in 2020 closed a major open cast site, Bradley mine, near Dipton in the county[7] and the last open cast site then operating in England, Hartington at Staveley, Derbyshire, also closed.[8][9] In 2020 Whitehaven coal mine became the first approved new deep coal mine in the United Kingdom in 30 years.[10]

Extent and geology

The United Kingdom's onshore coal resources occur in rocks of the Carboniferous age, some of which extend under the North Sea.[11] The carbon content of the bituminous coal present in most of the coalfields is 86% to 88%.[12] Britain's coalfields are associated with Northumberland and Durham, North and South Wales, Yorkshire, the Scottish Central Belt, Lancashire, Cumbria, the East and West Midlands and Kent.

History

Stone and Bronze Age flint axes have been discovered embedded in coal, showing that it was mined in Britain before the Roman invasion. Early miners first extracted coal already exposed on the surface and then followed the seams underground.[13]

It is probable that the Romans used outcropping coal when working iron or burning lime for building purposes. Evidence to support these theories comes mostly from ash discovered at excavations of Roman sites.[14]

There is no mention of coal mining in the Domesday Book of 1086 although lead and iron mines are recorded.[15] In the 13th century there are records of coal digging in Durham[16] and Northumberland,[17] Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, Staffordshire, Lancashire, the Forest of Dean, Prestongrange in Lothian [18] and North[19] and South Wales. At this time coal was referred to as sea cole, a reference to coal washed ashore on the north east coast of England from either the cliffs or undersea outcrops. As the supply of coal on the surface became used up, settlers followed the seam inland by digging up the shore. Generally the seam continued underground, encouraging the settlers to dig to find coal, the precursor to modern operations.[13]

The early mines would have been drift mines or adits where coal seams outcropped or by shallow bell pits where coal was close to the surface.[20] Shafts lined with tree trunks and branches have been found in Lancashire in workings dating from the early 17th century and by 1750 brick lined shafts to 150-foot (45 m) depth were common.

Industrial Revolution until 1900

Coal production increased dramatically in the 19th century as the Industrial Revolution gathered pace, as a fuel for steam engines such as the Newcomen engine, and later, the Watt steam engine. To produce firewood in the 1860s equivalent in energy terms to domestic consumption of coal would have required 25 million acres (100,000 km2) of land per year, nearly the entire farmland area of England (26 million acres (105,000 km2)).[21]

A key development was the invention at Coalbrookdale in the early 18th century of coke which could be used to make pig iron in the blast furnace. The development of the steam locomotive by Trevithick early in the 19th century gave added impetus, and coal consumption grew rapidly as the railway network expanded through the Victorian period. Coal was widely used for domestic heating owing to its low cost and widespread availability. The manufacture of coke also provided coal gas, which could be used for heating and lighting. Most of the workers were children and men.[22]

At the beginning of the 19th century methods of coal extraction were primitive and the workforce – men, women, and children – laboured in dangerous conditions. By 1841 about 216,000 people were employed in the mines. Women and children worked underground for 11 or 12 hours a day for smaller wages than men.[23] The public became aware of conditions in the country's collieries in 1838 after an accident at Huskar Colliery in Silkstone, near Barnsley. A stream overflowed into the ventilation drift after violent thunderstorms causing the death of 26 children; 11 girls aged from 8 to 16 and 15 boys between 9 and 12 years of age.[24] The disaster came to the attention of Queen Victoria who ordered an inquiry.[23] This led to the Mines and Collieries Act 1842, commonly known as the Mines Act 1842, an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which forbade women and girls of any age to work underground and introduced a minimum age of ten for boys employed in underground work.[23] However, the employment of women did not end abruptly in 1842; with the connivance of some employers, women dressed as men continued to work underground for several years. Penalties for employing women were small and inspectors were few and some women were so desperate for work they willingly worked illegally for less pay.[25] Eventually, the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 (c. 65), another act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, was passed protecting women – and men – from discrimination on the grounds of sex or marital status, including regarding employment as miners.[26] Also, children continued working underground at some pits after 1845. At Coppull Colliery's Burgh Pit, three females died after an explosion in November 1846; one was eleven years old.[27] The Mines (Prohibition of Child Labour Underground) Act 1900 was an Act of Parliament of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that prevented boys under the age of thirteen from working, or being (for the purposes of employment) in an underground mine.[28] (The act was repealed in full by the Mines and Quarries Act 1954 (c. 70);[29] by such time the act was out of date and was no longer necessary due to the stronger provisions in the Employment of Women, Young Persons, and Children Act 1920.[30])

Nationalisation

Until 1 January 1947 the mines were owned by various individuals and companies. On that date most were nationalised by Act of Parliament and were run by the new National Coal Board.[31] In March 1987 the legal name of the NCB was changed to the British Coal Corporation.[32] The name "British Coal" had been used by the NCB since 28 April 1986.[33]

Decline in volume

.jpg.webp)

UK coal production peaked in 1913 at 287 million tonnes.[4] Until the late 1960s, coal was the main source of energy produced in the UK, peaking at 228 million tonnes in 1952. Ninety-five per cent of this came from roughly 1,334 deep-mines that were operational at the time, with the rest from around 92 surface mines.[34]

In the 1950s and 1960s, around a hundred North East coal mines were closed.[35] In March 1968, the last pit in the Black Country closed and pit closures were a regular occurrence in many other areas.[36] Beginning with wildcat action in 1969, the National Union of Mineworkers became increasingly militant, and was successful in gaining increased wages in their strikes in 1972 and 1974.[37] Closures were less common in the 1970s, and new investments were made in sites such as the Selby Coalfield. In early 1984, the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher announced plans to close 20 coal pits which led to the year-long miners' strike which ended in March 1985. The strike was unsuccessful in stopping the closures and led to an end to the closed shop in British Coal, as the breakaway Union of Democratic Mineworkers was formed by miners who objected to the NUM's handling of the strike.[38] Numerous pit closures followed, and in August 1989 coal mining ended in the Kent coalfield.[39]

In 1986, Kellingley colliery near Pontefract achieved a record 404,000 tonnes in a single shift but nevertheless, since 1981 production fell sharply from 128 to 17.8 million tonnes in 2009.

Between 1947 and 1994, some 950 mines were closed by UK governments. Clement Attlee’s Labour government closed 101 pits between 1947 and 1951; Macmillan (Conservative) closed 246 pits between 1957 and 1963; Wilson (Labour) closed 253 in his two terms in office between 1964 and 1976; Heath (Conservative) closed 26 between 1970 and 1974; and Thatcher (Conservative) closed 115 between 1979 and 1990.[40]

In 1994, then-Prime Minister John Major privatised British Coal after announcing 55[40] further closures, with the majority of operations transferred to the new company UK Coal.[41][42] By this time British Coal had closed all but the most economical of coal pits.[43]

The pit closures reflected coal consumption slumping to the lowest rate in more than a century, further declining towards the end of the 1980s and into the 1990s. This coincided with initiatives for cleaner energy generation as power stations switched to gas and biomass. A total of 100 million tons was produced in 1986, but by 1995 the amount was around 50 million tons.[44] The last deep mine in South Wales closed when the coal was exhausted in January 2008. The mine was closed by British Coal in the privatisation of the industry fourteen years earlier and re-opened for 13 years after being bought by the miners who had worked at the pit.[45] British coal-dependent industries also turned to cheaper imported coal.[46]

In 2001, production was exceeded by imports for the first time. In 2014, coal imported was three times more than the coal mined in Britain.[47] In 2009, companies were licensed to extract 125 million tonnes of coal in operating underground mines and 42 million tonnes at opencast locations.[4]

Coal mining employed 4,000 workers at 30 locations in 2013, extracting 13 million tonnes of coal.[47] The UK Coal mines achieved the most economical coal production in Europe, according to UK Coal, with a level of productivity of 3,200 tonnes per man year as of 2012, at which point there were 13 UK Coal deep mines.[43] The three deep-pit mines were Hatfield and Kellingley Collieries in Yorkshire and Thoresby in Nottinghamshire.[1] There were 26 opencast sites in 2014, mainly in Scotland.[5] Most coal is used for electricity generation and steel-making, with its use for heating homes decreased because of pollution concerns. The commodity is also used for fertilisers, chemicals, plastics, medicines and road surfaces. Hatfield Colliery closed in June 2015, as did Thoresby, and in December 2015, Kellingley, bringing to an end deep coal mining in the UK. The occasion was marked by a rally and march attended by thousands of people.[48] The closure of coal mines left the affected communities economically deprived, unable to recover even in the long run.[49]

In 2020, the Woodhouse Colliery became the first approved new deep coal mine in the United Kingdom in 30 years.[10] The plan was criticised by some MPs and environmentalists due to the incompatibility of coal mining with government commitments to reduce carbon emissions. The mine is proposed by West Cumbria Mining and plans to extract coking coal from beneath the Irish Sea for 25 years.[50][51][52] The Cumbria County Council Development Control and Regulation Committee approved West Cumbria Mining plans for the mine in October 2020 for a third time.[53] In January 2021 Secretary of State Robert Jenrick refused South Lakeland MP Tim Farron's request to call in the plans for review.[54] Farron described the coal mine as a "complete disaster for our children's future".[54] Greenpeace UK stated “claims that it will be carbon neutral are like claiming an oil rig is a wind turbine”.[10]

Complete phase-out for electricity generation

The demand for coal is likely to fall with increasing focus on renewable energy or low-carbon sources and loss of industry due to globalisation. Oil and gas reserves are predicted to run out long before coal,[55] so gas could be produced from coal by gasification.[56]

On 21 April 2017, Britain went a full day without using coal power to generate electricity for the first time since the Industrial Revolution, according to the National Grid.[57] In May 2019, Britain went a full week without coal power.[58] Later in the year a new record of 18 days, 6 hours and 10 minutes was set.[59] In 2019, German utilities firm RWE announced that it planned to close all its UK coal power plants by 2020, leaving only four plants operating by March 2020;[60] in 2018, eight were still in operation when the government announced plans to shut down all coal power plants in the UK by 2025.[61] In June 2021, the government announced it was bringing forward the shutdown to 2024.[62]

See also

- Mines Act of 1842

- Mines (Prohibition of Child Labour Underground) Act 1900

- National Coal Board

- Three-Day Week

- Coal Mines (Emergency) Act 1920

- List of coal mines in the United Kingdom

- List of active coal-fired power stations in the United Kingdom

- National Coal Mining Museum for England

- Big Pit National Coal Museum, Wales

- National Mining Museum Scotland

References

- Seddon, Mark (10 April 2013). "The long, slow death of the UK coal industry" (The Northerner blog). The Guardian. London. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

Earlier this month Maltby colliery in South Yorkshire closed down for good. At the end of a winter that saw 40% of our energy needs met by coal – most of it imported – we witnessed the poignant closing ceremony

- "Digest of UK Energy Statistics (DUKES): solid fuels and derived gases". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, "Historical coal data: coal production, availability and consumption 1853 to 2015" (2016)

- "Mineral Profile - Coal". bgs.ac.uk. British Geological Society. March 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "Surface Coal Mining Statistics". www.bgs.ac.uk. 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "Banks Mining looking to operate Bradley surface mine in County Durham". www.banksgroup.co.uk. Banks Group. 4 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- "Bradley mine: Coal extracted for final time at County Durham site". BBC News. 17 August 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Ambrose, Jillian (22 August 2020). "Journey's end: last of England's open-cast mines begins final push". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- "The deadliest disasters in Derbyshire's mining history". Derbyshirelive. 9 January 2021.

- "Jenrick criticised over decision not to block new Cumbria coal mine". The Guardian. 6 January 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Survey, British. "Coal | Mines & quarries | MineralsUK". www.bgs.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "Types and uses of coal". www.ukcoal.com. UK Coal. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "Mining through the ages". ukcoal.com. UK Coal. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- Galloway 1971, p. 5

- Galloway 1971, p. 11

- The Durham Coalfield, Coalmining History Research Centre, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 5 December 2010

- The NorthumberlandCoalfield, Coalmining History Research Centre, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 5 December 2010

- Prestongrange: A Powerhouse of Industry

- The North Wales Coalfield, Coalmining History Research Centre, archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved 5 December 2010

- Galloway 1971, p. 20

- Clark, Gregory; Jacks, David (April 2006). "Coal and the Industrial Revolution, 1700-1869" (PDF). European Review of Economic History. 11 (1): 39–72. doi:10.1017/S1361491606001870. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- Making gas from coal, National Gas Museum, archived from the original on 17 July 2011, retrieved 6 December 2011

- "The Mines Act, 1842". University of Paris. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- "Huskar Colliery Disaster" (PDF). cmhrc.co.uk. p. 68. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- Women in mining communities (PDF), National Mining Museum, retrieved 20 November 2016

- https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1975/65/pdfs/ukpga_19750065_en.pdf

- Nadin, Jack (2006), Lancashire Mining Disasters 1835-1910, pg. 18, Wharncliffe Books, ISBN 1-903425-95-6

- Pipkin, Charles W. (2005). Reprint (ed.). Social Politics and Modern Democracies, Volume 2. Whitefish: Kessinger Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 1-4191-1091-8. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- "Mines and Quarries Act 1954". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- "Employment of Women, Young Persons, and Children Act 1920". legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

1(1): No child shall be employed in any industrial undertaking.

- Cavendish, Richard (1 January 1997). "Coal Industry comes under public industry in Britain". History Today. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- Rees, William (1987). "Recent Legislation". Industrial Law Journal. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- "Britain's Nationalised Coal Mines from 1947". Northern Mine Research Society. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- "Energy Trends: September 2014, special feature articles - Coal in 2013 - Publications - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. 25 September 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "Coal Mining in North East England". www.englandsnortheast.co.uk. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- Pearson, Mick. "The Closing Of Baggeridge Colliery (from "We Were There" Blackcountryman Volume 1, Issue 3)". blackcountrysociety.co.uk/. Black Country Society. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- Routledge, Paul (1994). Scargill: the unauthorised biography. London: Harper Collins. pp. 59–79. ISBN 0-00-638077-8.

- "1984: Miners strike over threatened pit closures". BBC News. 12 March 1984.

- Elmhirst, Sophie (22 June 2011). "After the coal rush". newstatesman.com. New Statesman. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "Colliery Closures Since 1947".

- "Leading Article: John Major: Is he up to the job?". The Independent. London. 4 April 1993.

- "BBC Wales - History - The Miners' Strike". BBC Wales. BBC. 15 August 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "UK Coal: Coal In Britain Today". UK Coal (Archived). Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "Thatcher years in graphics". BBC News. 18 November 2005.

- "Coal mine closes with celebration". BBC News. 25 January 2008.

- John F. Burnes (16 April 2013). "Whitwell Journal: As Thatcher Goes to Rest, Miners Feel No Less Bitter". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Historical coal data: coal production, availability and consumption 1853 to 2013 - Statistical data sets - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Department of Energy & Climate Change. 22 January 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "Thousands march through Yorkshire to mark end of deep coal mining at Kellingley". BBC News. 20 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- Aragon, Fernando; Rud, Juan Pablo; Toews, Gerhard (June 2018). "Resource shocks, employment, and gender: Evidence from the collapse of the UK coal industry". Labour Economics. 52: 54–67. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2018.03.007. S2CID 55765613.

- "Whitehaven coal mine approved for third time". BBC News. 3 October 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "Mixed reactions to news of West Cumbria Mining plans overcoming major hurdle". News and Star. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "Looking back at south Cumbria's extraordinary 2020". The Mail. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "Exciting new plans and a major launch but soaring Covid-19 infection rates – what happened in October 2020". The Mail. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "Whitehaven coal mine: Government refuses to call in plans". BBC News. 6 January 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "World Reserves of Fossil Fuels". Knoema. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- "Britain's largest coal mining company - Coal Today and for Tomorrow". UK Coal. 26 January 2012. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "First coal-free day in Britain since Industrial Revolution". BBC News. 22 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- Jolly, Jasper (8 May 2019). "Britain passes one week without coal power for first time since 1882". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- "UK's record coal free-run comes to an end". BusinessGreen. 5 June 2019. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- Ambrose, Jillian (1 August 2019). "German utilities firm RWE to close its last UK coal plant in 2020". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- Vaughan, Adam (5 January 2018). "UK government spells out plan to shut down coal plants". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- "UK to end coal power by 2024". airqualitynews.com. 30 June 2021.

Further reading

- Ashton, T. S. & Sykes, J. The coal industry of the eighteenth century. 1929.

- Baylies, Carolyn. The History of the Yorkshire Miners, 1881-1918 Routledge (1993).

- Benson, John. "Coalmining" in Chris Wrigley, ed. A History of British industrial relations, 1875-1914 (Univ of Massachusetts Press, 1982), pp 187–208.

- Benson, John. British Coal-Miners in the Nineteenth Century: A Social History (Holmes & Meier, 1980) online

- Buxton, N.K. The economic development of the British coal industry: from Industrial Revolution to the present day. 1979.

- Dintenfass, Michael. "Entrepreneurial failure reconsidered: the case of the interwar British coal industry." Business History Review 62#1 (1988): 1-34. in JSTOR

- Dron, Robert W. The economics of coal mining (1928).

- Ediger, Volkan Ş., and John V. Bowlus. "A farewell to King Coal: geopolitics, energy security, and the transition to oil, 1898–1917." Historical Journal 62.2 (2019): 427-449. online

- Fine, B. The Coal Question: Political Economy and Industrial Change from the Nineteenth Century to the Present Day (1990).

- Galloway, R.L. (1971). Annals of coal mining and the coal trade. First series [to 1835] 1898; Second series. [1835-80] 1904. Reprinted 1971

- Galloway, Robert L. A History Of Coal Mining In Great Britain (1882) Online at Open Library

- Griffin, A. R. The British coalmining industry: retrospect and prospect. 1977.

- Handy, L. J. Wages Policy in the British Coal Mining Industry: A Study of National Wage Bargaining (1981) excerpt

- Hatcher, John, et al. The History of the British Coal Industry (5 vol, Oxford U.P., 1984–87); 3000 pages of scholarly history

- John Hatcher: The History of the British Coal Industry: Volume 1: Before 1700: Towards the Age of Coal (1993). online

- Michael W. Flinn, and David Stoker. History of the British Coal Industry: Volume 2. 1700-1830: The Industrial Revolution (1984).

- Roy Church, Alan Hall and John Kanefsky. History of the British Coal Industry: Volume 3: Victorian Pre-Eminence

- Barry Supple. The History of the British Coal Industry: Volume 4: 1913-1946: The Political Economy of Decline (1988) excerpt and text search

- William Ashworth and Mark Pegg. History of the British Coal Industry: Volume 5: 1946-1982: The Nationalized Industry (1986) online

- Heinemann, Margot. Britain's coal: A study of the mining crisis (1944).

- Hill, Alan. Coal - a Chronology for Britain. Northern Mine Research Society.

- Hull, Edward (1861). The coal-fields of Great Britain: their history, structure, and resources. London: 1861: Stanford.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Hull, Edward. Our coal resources at the close of the nineteenth century (1897) Online at Open Library. Stress on geology.

- Jaffe, James Alan. The Struggle for Market Power: Industrial Relations in the British Coal Industry, 1800-1840 (2003). online

- Jevons, H.S. The British coal trade. 1920, reprinted 1969

- Jevons, W. Stanley. The Coal Question: An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal Mines (1865).

- Kirby, Maurice William. "The Control of Competition in the British Coal‐Mining Industry in the Thirties" Economic History Review 26.2 (1973): 273-284. in JSTOR

- Kirby, M.W. The British coalmining industry, 1870-1946: a political and economic history. 1977. online

- Langton, John, ed. Atlas of industrialising Britain 1780-1914 (Methuen, 1986) pp 72-79.

- Lucas, Arthur F. "A British Experiment in the Control of Competition: The Coal Mines Act of 1930." Quarterly Journal of Economics (1934): 418-441. in JSTOR

- Prest, Wilfred. "The British Coal Mines Act of 1930, Another Interpretation." Quarterly Journal of Economics (1936): 313-332. in JSTOR

- Lewis, B. Coal mining in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Longman, 1971.

- Mathis, Charles-François. "King coal rules: accepting or refusing coal dependency in Victorian Britain." Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique. French Journal of British Studies 23#3 (2018).

- Murray, John, and Javier Silvestre. "Integration in European Coal Markets, 1833–1913". Economic History Review 73 (2020) 668–702.

- Nef, J. U. Rise of the British coal industry. 2v 1932, a comprehensive scholarly survey

- Orwell, George. "Down the Mine" (The Road to Wigan Pier chapter 2, 1937) full text

- Rowe, J.W.F. Wages In the coal industry (1923).

- Tawney, R. H. "The British Coal Industry and the Question of Nationalization" The Quarterly Journal of EconomicsThe Quarterly Journal of Economics 35 (1920) online

- Waller, Robert. The Dukeries Transformed: A history of the development of the Dukeries coal field after 1920 (Oxford U.P., 1983) on the Dukeries

- Williams, Chris. Capitalism, community and conflict: The south Wales coalfield, 1898-1947 (U of Wales Press, 1998).

- Wrigley, Edward Anthony. Energy and the English Industrial Revolution (Cambridge University Press, 2010).