Uintatherium

Uintatherium ("Beast of the Uinta Mountains") is an extinct genus of herbivorous mammal that lived during the Eocene epoch. Two species are currently recognized: U. anceps from the United States during the Early to Middle Eocene (56–38 million years ago) and U. insperatus of Middle to Late Eocene (48–34 million years ago) China.[1]

| Uintatherium Temporal range: Eocene, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cast of the skeleton, French National Museum of Natural History in the Paris | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | †Dinocerata |

| Family: | †Uintatheriidae |

| Subfamily: | †Uintatheriinae |

| Genus: | †Uintatherium Leidy, 1872 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Genus synonymy

Synonyms of U. anceps

| |

Description

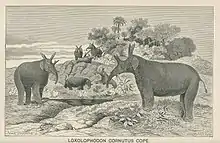

Uintatherium was a large browsing animal. With a skull 76 cm (30 in) long, 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) tall at the shoulder,[2] body length of about 4 m (13 ft) and a weight up to 2 tonnes, it was similar to today's rhinoceros, both in size and in shape.[3] Its legs were robust to sustain the weight of the animal and were equipped with hooves.[4] Moreover, a Uintatherium's sternum was made up of horizontal segments, unlike today's rhinos, which have compressed vertical segments.[5]

Skull

Its most unusual feature was the skull, which was large and strongly built, but simultaneously flat and concave: this feature is rare and is found in no other known mammal except some brontotheres. The cranial cavity was exceptionally small because the walls of the cranium were exceedingly thick. The cranium was lightened by several sinuses, like those in an elephant's skull.

The teeth were larger in males than in females. The upper canine teeth were large and may have been formidable defensive weapons;[2] superficially, they resembled those of saber-toothed cats. However, they also may have been used to pluck the aquatic plants from marshes that seem to have been the source of the uintatherium.

The front of the male's skull bore six knob-like ossicones, which projected 5–25 cm (2.0–9.8 in).[2] Their function is unknown. They may have been used in defense and/or sexual display.

Discovery and taxonomy

Fossils of Uintatherium were first discovered in the Bridger Basin near Fort Bridger by Lieutenant W. N. Wann in September 1870 and were later described as a new species of Titanotherium, Titanotherium anceps, by Othniel Marsh in 1871.[6] The specimen (YPM 11030) only consisted of several skull pieces, including the right parietal horn, and fragmentary postcrania.[6] The following year, Marsh and Joseph Leidy collected in the Eocene Beds near Fort Bridger while Edward Cope, Marsh's competitor, excavated in the Washakie Basin. In August 1872, Leidy named Uintatherium robustum based on a posterior skull and partial mandibles (ANSP 12607).[6][7] Another specimen discovered by Leidy's crews consisting of a canine was named Uintamastix atrox and was thought to have been a saber-toothed and carnivorous.[7]

Eighteen days after the description of Uintatherium, Cope and Marsh both named new genera of Uinta dinoceratans, Cope naming Loxolophodon in his "garbled" telegram[8] and Marsh dubbed Tinoceras.[9] Due to Uintatherium being named first, Cope and Marsh's genera are synonymous with Uintatherium.[6] Cope described two genera in his telegram, Loxolophodon and Eobasileus;[8][10] the latter is currently considered separate from Uintatherium.[6] Tinoceras was a new genus made for Titanotherium anceps by Marsh.[9][6] Several days later, Marsh erected the genus Dinoceras.[6] Dinoceras and Tinoceras would receive several additional species by Marsh throughout the 1870s and 1880s, many based on fragmentary material.[9][6] Several complete skulls were found by Cope and Marsh crews, leading to theories like Cope's proboscidean assessment.[10][11] Because of Cope and Marsh's rivalry, the two would often publish scathing criticisms of each other's work, stating their respective genera were valid.[6] The trio would name 25 species now considered synonymous with Marsh's original species, Titanotherium anceps, which was placed in Leidy's genus, Uintatherium.[6]

Many additional discoveries of Uintatherium have since occurred, making Uintatherium one of the best-known and popular American fossil mammals.[12][6] Princeton University launched expeditions to the Eocene beds of Wyoming in the 1870s and 1880s, discovering several partial since skulls and naming several species of uintatheres that are now considered synonyms of U. anceps.[13][6] Major reassesment came in the 1960s by Walter Wheeler who synonymized and re-described many of the Uintatherium fossils discovered during the 19th century[6] A cast of a Uintatherium skeleton is on display at the Utah Field House of Natural History State Park. The skeleton of Uintatherium is also on display at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC.[14] A new species was named based on almost intact skull, U. insperatus, found in the lower part of the Lushi Formation of the Lushi Basin in Henan Province, China.[1]

References

- Tong, Yongsheng; Wang Jingwen (July 1981). "A Skull of Uintatherium from Henan" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. XIX (3): 208–214.

- Rich, Patricia Vickers; Rich, Thomas Hewitt; Fenton, Mildred Adams; Fenton, Carroll Lane (15 January 2020). The Fossil Book: A Record of Prehistoric Life. Dover Publications. p. 555. ISBN 9780486838557. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- "Ice Age Mammals". EnchantedLearning.com. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- Leidy, Joseph (1873). "Contribution to the extinct vertebrate fauna of the Western Territories". Geological Survey of the Territories. 1.

- Marsh, Othniel Charles (1881). "Restoration of Dinoceras mirabile" (PDF). American Journal of Science. XXII: 31.

- Wheeler, W. H. (1961). "Revision of the Uintatheres" (PDF). Peabody Museum of Natural History Bulletin. Yale University. 14.

- Leidy, Joseph (1872). "On some new species of fossil mammalia from Wyoming". Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia Proc.: 240–242.

- Cope, Edward (1872). "Telegram describing extinct Proboscidians from Wyoming". Paleontological Bulletin. 5.

- Anonymous (1 March 1885). "Professor Marsh's monography of the dinocerata". American Journal of Science. s3-29 (171): 173–204. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-29.171.173. ISSN 0002-9599.

- Cope, E. D. (1873). "On the Short Footed Ungulata of the Eocene of Wyoming". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 13 (90): 38–74.

- Cope, E. D. (1873). "On Some of Prof. Marsh's Criticisms". The American Naturalist. 7 (5): 290–299.

- Wheeler, W. H. (1960). "The uintatheres and the Cope–Marsh war". Science. 131 (3408): 1171–1176. PMID 17773922.

- Scott, W. B. (1886). "On some new forms of the Dinocerata". Am. Jour. Sci. 31 (3): 303–307.

- "Paleobiology". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

Further reading

- Academy of Natural Sciences

- National Park Service

- Wood, Horace Elmer 1923, The problem of the Uintatherium molars, Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History ; v. 48, article 18

- Fossil Evidence – Eocene: Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History