Umm Kulthum

Umm Kulthum[lower-alpha 1] (31 December 1898[3][4] – 3 February 1975) was an Egyptian singer, songwriter, and film actress active from the 1920s to the 1970s. She was given the honorific title Kawkab al-Sharq ("Star of the East").[5] In her native Egypt, Kulthum is a national icon; she has been dubbed as "The Voice of Egypt"[6][7] and "Egypt's Fourth Pyramid".[8][9] In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked Kulthum at number 61 on its list of the 200 Greatest Singers of All Time.[10][11]

Umm Kulthum أم كلثوم | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Fatima Ibrahim as-Sayed El-Beltagi فاطمةإبراهيم السيد البلتاجي |

| Born | 31 December 1898 Tamay Ez-Zahayra, El Senbellawein, El Dakahlia, Khedivate of Egypt |

| Died | 3 February 1975 (aged 76) Cairo, Egypt |

| Genres | Egyptian music, classical |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Years active | 1923–1973 |

| Labels | Odeon His Master's Voice Cairophon Sono Cairo Mazzika EMI Classics EAC Records |

Biography

Early life

Umm Kulthum was born in the village of Tamay e-Zahayra, belonging to the city of Senbellawein, Dakahlia Governorate, in the Nile Delta[4] to a family with a religious background as her father Ibrahim El-Sayyid El-Beltagi was an imam from the Egyptian countryside, her mother was Fatmah El-Maleegi, a housewife.[4] She learned how to sing by listening to her father teach her older brother, Khalid. From a young age, she showed exceptional singing talent. Through her father, she learned to recite the Qur'an, and she reportedly memorized the entire book.[4] Her grandfather was also a well known reader of the Qur'an and she remembered how the villagers used to listen to him when he recited the Qur'an.[12] When she was 12 years old, having noticed her strength in singing, her father asked her to join the family ensemble, upon which she joined as a supporting voice, at the beginning just repeating what the others sang.[13] On stage, she wore a boy's cloak and bedouin head covering in order to alleviate her father's anxiety about her reputation and public performance.[13] At the age of 16, she was noticed by Mohamed Abo Al-Ela, a modestly famous singer, who taught her the old classical Arabic repertoire. A few years later, she met the famous composer and oudist Zakariyya Ahmad, who took her to Cairo. Although she made several visits to Cairo in the early 1920s, she waited until 1923 before permanently moving there. She was invited on several occasions to the home of Amin Beh Al Mahdy, who taught her to play the oud, a type of lute. She developed a close relationship with Rawheya Al-Mahdi, Amin's daughter, and became her closest friend. Umm Kulthum even attended Rawheya's daughter's wedding, although she ordinarily preferred not to appear in public (offstage).

During her early career years, she faced staunch competition from two prominent singers: Mounira El Mahdeya and Fathiyya Ahmad, who had similar voices. El Mahdeya's friend, who worked as an editor at Al-Masra, several times suggested that Umm Kulthum must have married one of the guests who frequently visited her household, to the extent that her father decided to return to the village they came from together with his family.[14] Her father would only change his mind upon the persuasive arguments of Amin Al Mahdi.[14] Following Umm Kulthum made a public statement regarding visits in her household, which she announced she would not receive.[15] in 1923 she struck a contract with Odeon records which by 1926 would pay her more than any other Egyptian musical artist per record.[16]

Professional career

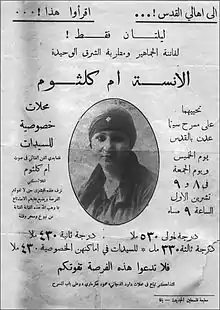

Amin El Mahdi invited her into the cultural circles in Cairo. In 1924, she was introduced to the poet Ahmed Rami,[17] who was to write 137 songs for her and also introduced her to French literature eventually becoming her head mentor in Arabic literature and literary analysis. In 1926, she left Odeon records for Gramophone records who would pay her about double per record and even an additional $10,000 salary.[16] She also maintained a tightly managed public image, which undoubtedly added to her allure. Furthermore, she was introduced to the renowned oud virtuoso and composer Mohamed El Qasabgi, who introduced her to the Arabic Theatre Palace, where she would experience her first real public success. Other musicians who influenced her musical performances at the time were Dawwod Hosni or Abu al-Ila Muhammad.[17] Al-Ila Muhammad instructed her in the control over her voice, and variants of the Arabic Muwashshah.[18] By 1930, she was so well known to the public, that she was the example to follow for several young female singers.[19] In 1932, she embarked upon a major tour of the Middle East and North Africa, performing in prominent Arab capital cities such as Damascus, Baghdad, Beirut, Rabat, Tunis, and finally Tripoli.

In 1934, Umm Kulthum sang for the inaugural broadcast of Radio Cairo, the state station.[20] From then on onwards, she performed at a concert on every first Thursday of a month for forty years.[13] Her influence kept growing and expanding beyond the artistic scene: the reigning royal family would request private concerts and even attend her public performances.

In 1944, King Farouk I of Egypt decorated her with the highest level of orders (nishan el kamal),[5] a decoration reserved exclusively to members of the royal family and politicians. Despite this recognition, the royal family rigidly opposed her potential marriage to the King's uncle, a rejection that deeply wounded her pride and led her to distance herself from the royal family and embrace grassroots causes, such as her answering the request of the Egyptian legion trapped in the Faluja Pocket during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War to sing a particular song. Among the army men trapped were the figures who were going to lead the bloodless revolution of 23 July 1952, prominently Gamal Abdel Nasser.

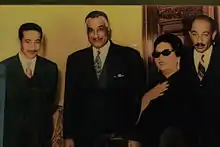

Following the revolution, the Egyptian musicians guild of which she became a member (and eventually president) rejected her because she had sung for the then-deposed King Farouk of Egypt. When Nasser discovered that her songs were banned from being aired on the radio, he reportedly said something to the effect of "What are they, crazy? Do you want Egypt to turn against us?"[21] Later, Nasser would schedule his speeches so they would not interfere with the radio performances of Umm Kulthum.[22]

Some claim that Umm Kulthum's popularity helped Nasser's political agenda. For example, Nasser's speeches and other government messages were frequently broadcast immediately after Umm Kulthum's monthly radio concerts. She sang many songs in support of Nasser, with whom she developed a close friendship. One of her songs associated with Nasser—"Wallāhi Zamān, Yā Silāḥī" ("It's Been a Long Time, O Weapon of Mine")—was adopted as the Egyptian national anthem from 1960 to 1979, when President Sadat revoked it because of the peace negotiations with Israel and replaced it by the less militant "Bilady, Bilady, Bilady", which continues to be Egypt's anthem today.[23][24]

Umm Kulthum was also known for her continuous contributions to works supporting the Egyptian military efforts.[5] Until 1972, for about half a century she gave at least one monthly concert.[25] Umm Kulthum's monthly concerts were renowned for their ability to clear the streets of some of the world's most populous cities as people rushed home to tune in.[26][25]

Her songs deal mostly with the universal themes of love, longing and loss. A typical Umm Kulthum concert consisted of the performance of two or three songs over a period of three to four hours. These performances are in some ways reminiscent of the structure of Western opera, consisting of long vocal passages linked by shorter orchestral interludes. However, Umm Kulthum was not stylistically influenced by opera, and she sang solo most of her career.

During the 1930s her repertoire took the first of several specific stylistic directions. Her songs were virtuosic, as befitted her newly trained and very capable voice, and romantic and modern in musical style, feeding the prevailing currents in Egyptian popular culture of the time. She worked extensively with texts by romance poet Ahmad Rami and composer Mohammad El-Qasabgi, whose songs incorporated European instruments such as the violoncello and double bass, as well as harmony. In 1936 she made her debut as an actress in the movie Weddad by Fritz Kramp.[27] During her career, she would act in five more movies, of which four would be directed by Ahmad Badrakhan[27] while Sallama and Fatma would be the most acclaimed.[28]

Golden age

Umm Kulthum's musical directions in the 1940s and early 1950s and her mature performing style led this period to becoming popularly known as "the golden age" of Umm Kulthum. In keeping with changing popular taste as well as her own artistic inclinations, in the early 1940s, she requested songs from composer Zakariya Ahmad and colloquial poet Mahmud Bayram el-Tunsi cast in styles considered to be indigenously Egyptian. This represented a dramatic departure from the modernist romantic songs of the 1930s, mainly led by Mohammad El-Qasabgi. Umm Kulthum had abstained from singing Qasabgi's music since the early 1940s. Their last stage song collaboration in 1941 was "Raq el Habib" ("The lover's heart softens"), one of her most popular, intricate, and high-caliber songs.

The reason for the separation is not clear. It is speculated that this was due in part to the popular failure of the movie Aida, in which Umm Kulthum sings mostly Qasabgi's compositions, including the first part of the opera. Qasabgi was experimenting with Arabic music, under the influence of classical European music, and was composing a lot for Asmahan, a singer who immigrated to Egypt from Syria and was the only serious competitor for Umm Kulthum before Asmahan's death in a car accident in 1944.

Simultaneously, Umm Kulthum started to rely heavily on a younger composer who joined her artistic team a few years earlier: Riad Al-Sunbati. While Sonbati was evidently influenced by Qasabgi in those early years, the melodic lines he composed were more lyrical and more acceptable to Umm Kulthum's audience. The result of collaborations with Rami/Sonbati and al-Tunisi/Ahmad was a populist and popular repertoire that had lasting appeal for the Egyptian audience.

In 1946, Umm Kulthum defied all odds by presenting a religious poem in classical Arabic. Salou Qalbi ["Ask My Heart"] was written by Ahmad Shawqi and composed by Ryad Al Sunbati.[7] The success was immediate and it reconnected Umm Kulthum with her early singing years. Similar poems written by Shawqi were subsequently composed by Sonbati and sung by Umm Kulthum, including Woulida el Houda ["The Prophet is Born"] 1949), in which she surprised royalists by singing a verse that describes Muhammad as "the Imam of Socialists". At the peak of her career, in 1950, Umm Kulthum sang Sonbati's composition of excerpts of what Ahmad Rami considered the accomplishment of his career: the translation from Persian into classical Arabic of Omar Khayyám's quatrains (Rubayyiat el Khayyam). The song included quatrains that deal with both epicurianism and redemption. Ibrahim Nagi's poem "Al-Atlal" ["The Ruins"] was sung by Umm Kalthum in a personal version and in a melody composed by Sonbati and premiered in 1966, is considered a signature song of hers.[7] As Umm Kulthum's vocal abilities had regressed considerably by then, the song can be viewed as the last example of genuine Arabic music at a time when even Umm Kulthum had started to compromise by singing Western-influenced pieces composed by her old rival Mohammed Abdel Wahab. The duration of Umm Kulthum's songs in performance was not fixed as upon the audience request for more repetitions, she would repeat the lines requested at length and her performances usually lasted for up to five hours, during which three songs were sung.[13] For example, the available live performances (about 30) of Ya Zalemni, one of her most popular songs, varied in length from 45 to 90 minutes, depending on both her creative mood for improvisations, illustrating the dynamic relationship between the singer and the audience as they fed off each other's emotional energy. An improvisatory technique, which was typical of old classical Arabic singing, and which she executed for as long as she could have (both her regressing vocal abilities with age and the increased Westernization of Arabic music became an impediment to this art), was to repeat a single line or stance over and over, subtly altering the emotive emphasis and intensity and exploring one or various musical modal scales (maqām) each time to bring her audiences into a euphoric and ecstatic state known in Arabic as "tarab" طرب.[13] Her concerts used to broadcast from Thursday 9.30 P.M., until the early morning hours on Friday.[7]

The spontaneous creativity of Umm Kulthum as a singer is most impressive when, upon listening to these many different renditions of the same song over a time span of five years (1954–1959), the listener is offered a totally unique and different experience. This intense, highly personalized relationship was undoubtedly one of the reasons for Umm Kulthum's tremendous success as an artist. Worth noting though that the length of a performance did not necessarily reflect either its quality or the improvisatory creativity of Umm Kulthum. Around 1965, Umm Kulthum started collaborating with composer Mohammed Abdel Wahab. Her first song composed by Abdel Wahab, "Enta Omri" ["You Are My Life"]. According to Frédéric Lagrange, professor at the Sorbonne University in Paris and specialist in Arab music, "this is an urban legend spread by ill-informed people who would rather check the reality of their information before publishing it"[29].Another source mentions the creation of a song of war.[30] Laura Lohman[31] has identified several other war songs created for her in that same period. In 1969 it was followed by another, Asbaha al-Ana 'indi Bunduqiyyah ["I now have a rifle"].[32] Her songs took on more a soul-searching quality in 1967 following the defeat of Egypt during the Six-Day War. Hadeeth el Rouh ["sermon of the soul"], which is a translation from the poet Mohammad Iqbal's "Shikwa", set up a very reflective tone. Generals in the audience are said to have been left in tears. Following the formation of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in 1971, she staged several concerts upon invitation of its first president Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan to celebrate the event.[33]

Umm Kulthum also sang for composers Mohammad El Mougi, Sayed Mekawy, and Baligh Hamdi.

Death and funeral

Umm Kulthum died on 3 February 1975 aged 76, from kidney failure before she could finish and sing her two songs ''Awkaty btehlaw ma'aak wa hyaty btekmal b'redak'' and another song that she asked for the poet Saleh Goudet to write for her to sing to commemorate the victory of Egypt in the October War (also known as: Yom kippur war) against Israel. She died before she was able to perform it on the second anniversary of the war. Her funeral procession was held at the Omar Makram mosque and became a national event, with around 4 million[34] Egyptians lining the streets to catch a glimpse as her cortège passed.[3] Her funeral's attendance drew a greater audience than the one of the Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser.[35][19] In the area where the funeral procession took place, traffic was cut off two hours ahead of the procession. The mourners would also wrest the casket from the shoulders of its bearers, force the procession to change its direction[19] and brought her coffin to the prominent Al Azhar mosque.[25] She was buried in a Mausoleum close to the Mausoleum of Imam al-Shafi'i in the City of the Dead in Cairo.[22] Her death was a great tragedy for the country and also acquired international media attention as news of her death was reported by the American Times magazine and the German Süddeutsche Zeitung magazine.

Artistic legacy

Umm Kulthum is regarded as one of the greatest singers in the history of Arab music,[36] with significant influence on a number of musicians, both in the Arab World and beyond. Jah Wobble has cited her as a significant influence on his work, and Bob Dylan has been quoted praising her as well.[37][38] Maria Callas,[39] Marie Laforêt,[40] Bono,[40] and Robert Plant,[41] among many other artists, are also known admirers of Kulthum's music. Youssou N'Dour, a fan of hers since childhood, recorded his 2004 album Egypt with an Egyptian orchestra in homage to her legacy.[42] One of her best-known songs, "Enta Omri", has been covered and reinterpreted numerous times. "Alf Leila wa Leila" was translated into jazz on French-Lebanese trumpeter Ibrahim Maalouf's 2015 album Kalthoum.[43]

She was referred to as "the Lady" by Charles de Gaulle and is regarded as the "Incomparable Voice" by Maria Callas. It is difficult to accurately measure her vocal range at its peak, as most of her songs were recorded live. Even today, she has retained a near-mythical status among young Egyptians and the whole of the Arabic World. In 2001, the Egyptian government opened the Kawkab al-Sharq ("Star of the East") Museum in the singer's memory. Housed in a pavilion on the grounds of Cairo's Manesterly Palace, the collection includes a range of Umm Kulthum's personal possessions, including her trademark sunglasses and scarves, along with photographs, recordings, and other archival material.[44]

Her performances combined raw emotion and political rhetoric; she was greatly influential and spoke about politics through her music. An example of this is seen in her music performed after World War II. The theme at the surface was love, yet a deeper interpretation of the lyrics – for example in the song "Salue Qalbi" – reveals questioning of political motives in times of political tension.[35] Umm Kulthum's political rhetoric in her music is still influential today, not only in Egypt, but in many other Middle Eastern countries and even globally. Her entire catalogue was acquired by Mazzika Group in the early 2000s.

Umm Kulthum is also notable in Baghdad due to her two visits, first in November 1932 and second in 1946 in which she was invited by Regent Abd al-Ilah. During those two visits, the Iraqi artistic, social and political circles took an interest in Umm Kulthum, and as a result, a large number of her fans and her voice lovers opened dozens of cafés that bore her name in different places. Today, only one of these cafés is preserved on al-Rasheed Street and is still associated with her.[45]

Voice

Umm Kulthum was a contralto.[46] Contralto singers are uncommon and sing in the lowest register of the female voice.[47] According to some, she had the ability to sing as low as the second octave and as high as the eighth octave at her vocal peak. Her incredible vocal strength, with the ability to produce 14,000 vibrations per second with her vocal chords, required her to stand three feet away from the microphone.[48] She was known to be able to improvise and it was said that she would not sing a line the same way twice.[13] She was a student of Abu al-Ila Muhammad from soon after she arrived in Cairo to when he died in 1927. He taught her to adapt her voice to the meaning and the melody in a traditional Arabic aesthetic.[49]

Remembrance

She is referenced at length in the lyrics of the central ballad "Omar Sharif" in the musical The Band's Visit.[50] A pearl necklace with 1,888 pearls, which she received from Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, is exhibited at the Louvre in Abu Dhabi.[33] Even 40 years after her death, at 10PM on the first Thursday of each month, Egyptian radio stations would broadcast only her music in her memory.[4]

In January 2019, at the Winter in Tantora festival in Al-'Ula, a live concert was performed for the first time with her "appearing as a hologram with accompaniment by an orchestra and bedecked in flowing, full-length gowns as she had when debuting in the 1920s."[51] Hologram concerts featuring her have been organized also by the Egyptian Minister of Culture Inas Abde-Dayem in Cairo and the Dubai Opera[5] Establishing a private museum for the Egyptian artist, Umm Kulthum, in 1998, and won awards.[52][53][54][55]

Notable songs

| Year | Title | Translation | Label | Lyricist | Composer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1944 | Ghaneely Shwaya Shwaya (from the film "Sallama") |

Sing Softly for Me | Orient | Bayram al-Tunisi | Zakaria Ahmed |

| 1945 | Biridaak ya Khalikee | By your pleasure my Creator | Orient | Bayram al-Tunisi | Zakaria Ahmed |

| 1946 | Walad Al Hoda | Child of Guidance | Cairophon | Ahmed Shawki | Riad Al Sunbati |

| 1960 | Howa Saheeh El Hawa Ghallab | It's True That Love Is Overpowered | Sono Cairo | Ma'moun El Shinnawi | Baligh Hamdi |

| 1961 | Hayyart Alby | You Confused My Heart | Philips | Ahmed Rami | |

| 1962 | Ha Seebak Lezzaman | I'm Going to Leave You | Mohammed Abdel Wahab | Riad Al Sunbati | |

| 1963 | Betfakker Fe Meen | Who Are You Thinking of | Sono Cairo | Ma'moun El Shinnawi | Baligh Hamdi |

| La Ya Habibi | No My Love | Philips | Abdel Fattah Mustafa | Riad Al Sunbati | |

| Lel Sabre Hedoud | Limits to Patience | Sono Cairo | Mohammed El Mougi | Mohammed Abdel Wahab | |

| 1964 | Seeret Hob | Love Story | Morsi Gamil Aziz | Baligh Hamdi | |

| Inta Omri | You Are My Life | Ahmed Shafik Kamel | Mohammed Abdel Wahab | ||

| 1965 | Inta Al Hob | You're Love | Ahmed Rami | ||

| Amal Hayaty | Hope of My Life | Ahmed Shafik Kamel | |||

| 1966 | Al Atlal | The Ruins | Ibrahim Nagi | Riad Al Sunbati | |

| Fakkarouny | They reminded Me | Mohammed Abdel Wahab | Mohammed Abdel Wahab | ||

| Hagartak | I Left You | Ahmed Rami | Riad Al Sunbati | ||

| 1967 | Hadeeth El Rouh | The Language of the Soul | Mohammed Iqbal | ||

| El Hob Keda | That's How Love Is | Bayram al-Tunisi | |||

| Awedt Eni | I Got Used to Your Sight | Ahmed Rami | Riad Al Sunbati | ||

| Fat Al Mi'aad | Too Late | Morsi Gamil Aziz | Baligh Hamdi | ||

| 1968 | Ruba'iyat Al Adawiya | The Quatrains of Adawiya | Tahar Aboufacha | Riad Al Sunbati | |

| Hathihy Leilty | This Is My Night | Mohammed Abdel Wahab | Georges Gerdaq | ||

| 1969 | Alf Leila W Leila | 1001 Nights | Morsi Gamil Aziz | Baligh Hamdi | |

| Aqbel Al Leil | The Night Is Coming | Ahmed Rami | Riad Al Sunbati | ||

| Arooh Lemeen | Who Do I Go to | Abdel Munaim al-Siba'i | |||

| 1970 | Es'al Rohak | Ask Yourself | Mohammed El Mougi | Mohammed Abdel Wahab | |

| Zekrayat | Souvenirs | Ahmed Rami | Riad Al Sunbati | ||

| El Hob Kollo | All the Love | Ahmed Shafik Kamel | Baligh Hamdi | ||

| Ruba'iyat Al Khiyam | The Quatrains of the Tents | Ahmed Rami | Riad Al Sunbati | ||

| W Marret Al Ayam | And the Days Passed | Ma'moun El Shinnawi | Mohammed Abdel Wahab | ||

| 1971 | Al Thulathiya Al Muqaddassa | The Holy Tercet | Saleh Gawdat | Riad Al Sunbati | |

| Mesh Momken Abadan | Impossible At All | Ma'moun El Shinnawi | Baligh Hamdi | ||

| El Alb Ye'sha' | The Heart Loves | Bayram al-Tunisi | Riad Al Sunbati | ||

| Aghda Al'ak' | Longing for You | ||||

| Al Amal | Hope | Zakaria Ahmed | |||

| 1972 | Raq El Habib | Vengeance of the Lover | Ahmed Rami | Mohamed El Qasabgi | |

| Lasto Fakir | I'm Still Thinking | Abdel Fattah Mustafa | Riad Al Sunbati | ||

| Ya Masharny | The One Who's Keeping Me Up | Ahmed Rami | Sayed Mekawy | ||

| 1973 | Hakam Alayna Al Hawa | We're in the Hands of Love | Mohammed Abdel Wahab | Baligh Hamdi | |

| Ahl El Hawa | The Lovers | Bayram al-Tunisi | Zakaria Ahmed | ||

| Yally Kan Yeshguik 'Anni | Whoever Talked to You About Me | Ahmed Rami | Riad Al Sunbati | ||

| Sahran La Wahdi | Up on My Own | ||||

| Daleely Ahtar | I'm Confused | ||||

| 1974 | Shams El Aseel | The Lovers | Bayram al-Tunisi | ||

| Ana Fe Intizarak | I"m Waiting for You | Zakaria Ahmed | |||

| 1975 | Ya Toul 'Azaby | My Suffering | Cairophon | Ahmed Rami | Riad Al Sunbati |

| Salu Qalby | Ask My Heart | Relax-In | Ahmed Shawqi | ||

| Ozkourini | Think of Me | Cairophon | Ahmed Rami | ||

| Aghar Min Nesmat Al Gnoub | Jealous of the Southern Breeze | Sono Cairo | |||

| Al Oula Fel Gharam | The Best at Falling in Love | Bayram al-Tunisi | Zakaria Ahmed | ||

| 1976 | Misr Tatahaddath 'an Nafsaha | Egypt Speaks of Itself | Hafez Ibrahim | Riad Al Sunbati | |

| Helm | Dream | Bayram al-Tunisi | Zakaria Ahmed | ||

| Al Ahat | The Groans | ||||

| Arak Assi Addame' | I See You Crying | Abu Firas al-Hamdani | Riad Al Sunbati | ||

| 1978 | Sourat Al Shakk | Doubt | Abdallah Al Faisal | ||

Filmography

Notes

References

- "Umm Kulthum Ibrahim". Harvard Magazine. 1 July 1997.

- "Umm Kulthum: An Outline of her Life". almashriq.hiof.no.

- "Umm Kulthūm". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2012.

- Nur, Yusif (20 February 2015). "Umm Kulthum: Queen Of The Nile". The Quietus. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "Egypt's Umm Kulthum hologram concerts to take place at the Abdeen Palace on November 20,21". Egypt Today. 14 November 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- Umm Kulthum: A Voice Like Egypt. 22 May 2007.

- Danielson, Virginia (1996). "Listening to Umm Kulthūm". Middle East Studies Association Bulletin. 30 (2): 170–173. doi:10.1017/S0026318400033976. ISSN 0026-3184. JSTOR 23061883. S2CID 152080002.

- "Umm Kulthoum, the fourth pyramid". 2008.

- Umm Kulthum, homage to Egypt's fourth pyramid

- Rolling Stone Magazine named iconic singer Umm Kulthum among the greatest 200 singers of all time., 8 January 2023

- "The 200 Greatest Singers of All Time". Rolling Stone. 1 January 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- Danielson, Virginia (1987). "The "Qur'an" and the "Qasidah": Aspects of the Popularity of the Repertory Sung by Umm Kulthūm". Asian Music. 19 (1): 27. doi:10.2307/833762. ISSN 0044-9202. JSTOR 833762.

- Faber, Tom (28 February 2020). "'She exists out of time': Umm Kulthum, Arab music's eternal star". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- Danielson, Virginia (10 November 2008). "The Voice of Egypt": Umm Kulthum, Arabic Song, and Egyptian Society in the Twentieth Century. University of Chicago Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-226-13608-0.

- Danielson, Virginia (10 November 2008), p.64

- Danielson, Virginia (10 November 2008), pp.54–55

- Danielson, Virginia (10 November 2008), p.56

- Danielson, Virginia (10 November 2008), pp.56–57

- Danielson, Virginia (1987), p.29

- Danielson, Virginia (2001). "Umm Kulthum [Ibrāhīm Um Kalthum]". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- Umm Kulthum: A Voice Like Egypt. Dir. Michal Goldman. Narr. Omar Sharif. Arab Film Distribution, 1996.

- "In search of Umm Kulthum's grave: where the lady rests". The National. 4 August 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- Danielson, Virginia (10 November 2008). "The Voice of Egypt": Umm Kulthum, Arabic Song, and Egyptian Society in the Twentieth Century. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226136080 – via Google Books.

- "Umm Kulthum – Egyptian musician – Britannica.com". 5 June 2016. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Egyptians Throng Funeral of Um Kalthoum, the Arabs' Acclaimed Singer (Published 1975)". The New York Times. 6 February 1975. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "Umm Kulthum: 'The Lady' Of Cairo". NPR.org. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "Film card". Torino Film Fest. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- "Biography | Umm Kulthum". albustanseeds.org. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- "A propos d'Oum Kalsoum". Libération (in French). Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Trost, Ernst (6 August 1967). "David und Goliath: Die Schlacht um Israel 1967". Molden – via Google Books.

- Lohman, Laura (1 February 2011). Umm Kulthum: Artistic Agency and the Shaping of an Arab Legend, 1967–2007. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 9780819570734 – via Google Books.

- "Liberating Songs: Palestine Put to Music – The Institute for Palestine Studies". palestine-studies.org.

- "Umm Kulthum brought back to life in unique Dubai 3D concert treatment". The DAIMANI Journal. 7 August 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- "Kumbh together". The Economist. 15 January 2013.

- Danielson, Virginia. "Listening to Umm Kulthūm." Middle East Studies Association Bulletin, vol. 30, no. 2, 1996, pp. 170–173.

- "Four decades on, the legacy of Umm Kulthum remains as strong as ever". Arab News. 6 February 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- "Playboy Interview: Bob Dylan". Interferenza.com. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- Piazza, Tom (28 July 2002). "Bob Dylan's Unswerving Road Back to Newport". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- "Umm Kulthum: Pride of Egypt". Archived from the original on 24 December 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- "Old is gold: Vintage photos of a chic Umm Kulthum in Paris!". 4 October 2015.

- Andy Gill (27 August 2010). "Robert Plant: 'I feel so far away from heavy rock'". The Independent. UK. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- Pascarella, Matt. "A Voice from Senegal: Youssou N'Dour". Retrieved 23 October 2010.

'Umm Kulthum was something that we could all share – throughout the Muslim world, despite our differences, her music brought people together,' he says. 'Although I haven't done anything close to what Umm did in music, I'm trying to be part of that musical tradition. For me, through Umm, Egypt became more than a country, it is a concept of meeting, of sharing what we have in common.' 'The Egypt album was my homage to Umm's legacy.'

- "Iconic French-Lebanese musician Ibrahim Maalouf to give first Egypt concert – Music – Arts & Culture – Ahram Online". english.ahram.org.eg. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- Rakha, Youssef and El-Aref, Nevine, "Umm Kulthoum, superstar" Archived 22 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Al-Ahram Weekly, 27 December 2001 – 2 January 2002.

- "مقهى أم كلثوم في بغداد ما زال محافظاً على عهدها رغم تغيير اسمه". aawsat.com (in Arabic). Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- "Funeral for a Nightingale". Time. 17 February 1975. Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- Owen Jander, et al. "Contralto". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press.

- Stanton, Andrea L. (2012). Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. SAGE. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-4129-8176-7.

- Danielson, Virginia (10 November 2008), p.57

- Kircher, Madison Malone (31 May 2018). "How Broadway's Tiny Musical Made Its Big Song". Vulture. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "Umm Kulthum returns virtually for Tantora show in Al-Ula". Arab News. 27 January 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "Cairo Museums details". www.cairo.gov.eg. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- "متاحف القاهرة". www.cairo.gov.eg. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- "متحف أم كلثوم... شاهد على عصر كوكب الشرق". اليوم السابع (in Arabic). 14 May 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- هنداوي, أسماء (1 March 2022). "متحف "أم كلثوم".. صرح فني ثقافي يأخذك برحلة عبر الزمن". منصة كلمتنا (in Arabic). Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0237908 IMDB

- https://elcinema.com/en/work/1005927 El-Cinema

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0237487 IMDB

- https://elcinema.com/en/work/1004598 El-Cinema

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0237133 IMDB

- https://elcinema.com/en/work/1502168 El-Cinema

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0237016 IMDB

- https://elcinema.com/en/work/1008811 El-Cinema

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0237688 IMDB

- https://elcinema.com/en/work/1011672 El-Cinema

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0237233 IMDB

- https://elcinema.com/en/work/1001660 El-Cinema

Sources

- Danielson, Virginia (1997). The Voice of Egypt: Umm Kulthum, Arabic Song, and Egyptian Society in the Twentieth Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Virginia Danielson. "Umm Kulthūm". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 20 July 2016.

- Halfaouine: Boy of the Terraces (film, 1990). This DVD contains an extra feature short film that documents Arab film history, and it contains several minutes of an Umm Kulthum public performance.

- "Umm Kulthoum". Al-Ahram Weekly. 3–9 February 2000. Archived from the original on 29 August 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2006. – articles and essays marking the 25th anniversary of the singer's death

- "Profile of Umm Kulthum and her music that aired on the May 11, 2008, broadcast of NPR's Weekend Edition Sunday". NPR.org.

- "Adhaf Soueif on Um Kulthum". Great Lives. BBC Radio 4. 22 November 2002. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- BBC World Service (2 February 2012). "Um Kulthum". Witness (Podcast). Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- "Oum Kalsoum exhibition at the Institute Du Monde Arabe, Paris, France". Archived from the original on 8 September 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2008. from Tuesday, 17 June 2008 to Sunday, 2 November 2008

- "Umm Kulthum lyrics and English translation". Arabic Song Lyrics. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- Murat Özyıldırım, Arap ve Turk Musikisinin 20. yy Birlikteligi, Bağlam Yay. (Müzik Bilimleri Serisi, Edt. V. Yildirim), Istanbul Kasım 2013.