Union Chapel, Brighton

The Union Chapel, also known as the Union Street Chapel, Elim Free Church, Four Square Gospel Tabernacle or Elim Tabernacle of the Four Square Gospel, is a former chapel in the centre of Brighton, a constituent part of the city of Brighton and Hove, England. After three centuries of religious use by various congregations, the chapel—which had been Brighton's first Nonconformist place of worship—passed into secular use in 1988 when it was converted into a pub. It was redesigned in 1825, at the height of Brighton's Georgian building boom, by at least one of the members of the Wilds–Busby architectural partnership, Brighton's pre-eminent designers and builders of the era, but may retain some 17th-century parts. It has been listed at Grade II in view of its architectural importance.

| Union Chapel | |

|---|---|

%252C_Union_Street%252C_Brighton.jpg.webp) The façade viewed from the southwest | |

| Location | Union Street, The Lanes, Brighton, Brighton and Hove BN1 1HA, England |

| Coordinates | 50.8223°N 0.1410°W |

| Founded | 1683 |

| Built | 1683, 1688 or 1698 |

| Built for | Presbyterian Church |

| Rebuilt | 1825 |

| Architect | Amon Wilds; possible involvement of Amon Henry Wilds and Charles Busby |

| Architectural style(s) | Classical |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | Elim Tabernacle and attached railings |

| Designated | 20 August 1971[1] |

| Reference no. | 481384 |

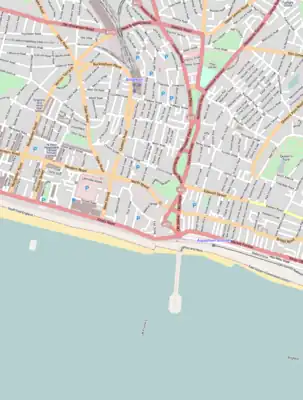

Location of Union Chapel in Brighton | |

History

Although evidence of Neolithic settlement has been found in the area now occupied by the city,[2] Brighton started to develop as a fishing village in the 12th century. Fishermen's houses were clustered together below the cliffs on the English Channel coast, a parish church (St Nicholas' Church) was built on higher ground to the northwest, and development gradually spread to the land immediately above the cliffs. By the 17th century, four streets named after the cardinal directions formed the boundaries of the village.[3]

Until that time, St Nicholas' Church was the only place of worship in Brighton.[4] Nationally, only the Church of England was recognised as legitimate. Various Acts of Parliament proscribed Roman Catholic and Nonconformist worship: in particular, the Conventicle Act 1664 prevented groups of non-Anglican Christians meeting for worship.[5][6] By about 1660, however, a Nonconformist community had developed sufficiently to be able to found a school. A religious census carried out in 1676 found 260 Nonconformists,[7] 8% of the village's population of 3,340.[8] As restrictions on their religious practices eased, a chapel was built; this was initially used by Presbyterians.[4] It was built in the heart of the old village on a street which was later named Union Street in reference to the chapel.[5] Sources disagree on the date of its founding and construction. Many identify 1683,[4][9][10][11] others prefer 1698,[5][6][12] and 1688 has also been put forward as the date of construction[13] or the date the land was sold to the Presbyterian community.[5] A foundation stone still exists in the south wall, but its date has been identified as either 1683[11] or 1688.[5]

%252C_Brighton.jpg.webp)

In its early years, the chapel was used exclusively by Presbyterians; but its first permanent minister—Reverend John Duke, who was in charge between 1698 and 1745—allowed Independent Christian ministers to hold services there as well. The name "Union Chapel" was adopted to reflect the coming together of the different denominations.[5] The name "Union Street Chapel" was also used occasionally after the street took that name.[14]

In around 1800, a house was constructed next to the chapel for the incumbent minister to live in, and burials began to be made in the former yard area behind the building. About ten years later, the chapel was extended; the east wall, built of cobbled stones and flints with red-brick dressings in a style found frequently in Sussex, may date from that redevelopment,[14] although other sources state it may have been part of the original 17th-century structure.[6][11]

Brighton grew rapidly, from its original fishing village status to a fashionable town and seaside resort, from the second half of the 18th century, helped by royal patronage, local doctor Richard Russell's advocacy of sea-bathing and seawater-drinking as a cure for various ailments, and improved transport connections to London and other places.[9][15] By the early 19th century, demand for new buildings—especially in the fashionable Regency style—was very high, and a group of three builders and architects, who worked together and separately at different times, became the most significant contributors to Brighton's building stock of the period.[16] Amon Wilds and his son Amon Henry Wilds, together with Charles Busby, were responsible for developments such as Kemp Town, the Brunswick estate, Regency Square, the Royal Albion Hotel and various churches.[17] The Union Chapel was completely redesigned in 1825 in a Classical style with Greek Revival and Egyptian Revival elements, and at least one member of the group was responsible; but there is disagreement over their respective contributions. Most sources identify Amon Wilds as being solely responsible;[10][11][13][18][19][20] others name Charles Busby on his own,[6] in collaboration with Amon Henry Wilds,[1][14] or even together with Amon Wilds senior.[12] Research by English Heritage in 1992 suggested that ascribing the work to Amon Wilds senior was a mistake; that the design was created by Charles Busby in 1825 when he was still in partnership with Amon Henry Wilds; that both men signed it; and that after the partnership was split up later in 1825, Wilds took responsibility for the work.[1]

%252C_Brighton.jpg.webp)

At the time of the reconstruction, the chapel was still in use by both Presbyterians and Independents, but by 1838 it was used solely by the latter. This development came during the 37-year incumbency of Reverend John Nelson Goulty, who became the minister in 1824.[14] Reverend George Wade Robinson, a well-respected preacher (The Philosophy of the Atonement & Other Sermons, E.P. Dutton Co. New York, 1912), poet, and hymn writer (I am His and He is mine, often sung to a tune by Rev. James Mountain), is known to have preached here in the early 1870s. Some interior remodelling was carried out in 1875, and a new minister—Reverend Reginald Campbell—reinvigorated the chapel's fortunes at the end of the 19th century after a period of stagnation.[21][22] Around the same time, another Nonconfirmist chapel in Brighton—the Queen Square Congregational Church, founded in 1853—was experiencing falling congregations, and sought a merger with the Union Chapel, whose ecclesiastical practices were compatible. The churches merged in around 1898; Reverend Campbell was the minister. The name "Union Church" was adopted.[22]

In 1905, the congregation moved permanently to the larger church on Queen Square, after a period in which both buildings were used, and Union Chapel was sold and became an Evangelical mission hall—the Glynn Vivian Miners' Mission. It was sponsored by Richard Glynn Vivian, a Welsh industrialist. He was converted to Evangelical Christianity while staying in Brighton after suddenly losing his sight, and devoted the rest of his life to improving the working and spiritual lives of miners in Britain and elsewhere.[23] The Union Chapel was the base for this work from 1905 until 1927[1] or 1931,[23] when the Elim Pentecostal Church bought it. It became known as the Elim Free Church or the Elim Tabernacle of the Four Square Gospel, and internal alterations removed almost all the interior fittings from the 1825 reconstruction.[23] In September 1988, the Elim congregation left the building and it was put up for sale again, with the expectation that it would become a restaurant or pub—ending 300 years of religious worship on the site.[1][6][12] The building was acquired by the Firkin Brewery, a pub chain established in 1979 which was experiencing significant growth by the early 1990s. They named it the "Font & Firkin", and installed a microbrewery on site.[24]

Architecture

The building is a dominant presence on the north side of Union Street,[10] now a very narrow pedestrianised passage in the heart of The Lanes, the series of passageways lined with old buildings which formed the centre of the ancient village.[6] The tall, wide, stuccoed façade, facing south, is in the Greek Revival style, with Doric pilasters, a triglyph and a large pediment—in keeping with many of the Wilds–Busby partnership's Regency era buildings in Brighton; but the two doorways and three windows are tapered from bottom to top, a feature associated with Egyptian Revival architecture.[10][12][14][20] The roof is partly gabled.[1] The east wall, facing Meeting House Lane, pre-dates the 1825 work on the main façade; it consists of cobbled stonework and flints in a regular pattern, with red-brick dressings at the corners and around the arch-headed sash windows on the ground floor and the larger rectangular first-floor sash windows.[1][11]

The interior has been changed since the building entered commercial use. There had been a gallery around three sides, reached by a pair of staircases from immediately inside the doorways. The gallery was held up by a series of cast iron columns with decorative capitals,[14] and was the only 19th-century feature to survive during the Elim congregation's occupancy.[23] The pulpit had stood in the centre of three arches in the north wall.[25] Pews were arranged in a semicircle facing it.[10][20]

The building today

After the Elim congregation vacated the building, it was converted into a large pub, the Font & Firkin—part of the former Firkin Brewery chain.[26] This was later disestablished, all of its pubs were sold and all in-pub brewing was stopped; the Font & Firkin was the last ex-Firkin pub in Britain to stop, in 2003.[24] The pub is still open and now trading as simply The Font.

The building was listed at Grade II on 20 August 1971.[1] It is one of 1,124 Grade II-listed buildings and structures, and 1,218 listed buildings of all grades, in the city of Brighton and Hove.[27]

Notes

- Historic England (2007). "Elim Tabernacle and attached railings, Union Street (north side), Brighton (1381041)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- Dale 1950, p. 9.

- Dale 1950, pp. 10–11.

- Berry 2005, p. 8.

- Dale 1989, p. 161.

- Carder 1990, §115.

- Carder 1990, §150.

- Berry 2005, p. 9.

- Dale 1950, p. 27.

- School of Architecture and Interior Design 1987, p. 38.

- Musgrave 1981, pp. 197–198.

- Elleray 2004, p. 10.

- Gilbert 1954, p. 103.

- Dale 1989, p. 162.

- Dale 1950, p. 19.

- School of Architecture and Interior Design 1987, p. 12.

- School of Architecture and Interior Design 1987, pp. 12–18.

- School of Architecture and Interior Design 1987, p. 15.

- Dale 1950, p. 28.

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 437.

- Dale 1989, p. 165.

- Dale 1989, p. 166.

- Dale 1989, p. 167.

- "The Directory of UK Real Ale Breweries: Firkin Brewery". The Directory of UK Real Ale Breweries website. The Directory of UK Real Ale Breweries. 2005-06-26. Archived from the original on 2005-06-17. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- Dale 1989, p. 163.

- "Font & Firkin — The Lanes — Brighton Pub Guide". Carling "Beerfinder" website. Coors Brewers Ltd. 2007. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- "Images of England — Statistics by County (East Sussex)". Images of England. English Heritage. 2007. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

Bibliography

- Berry, Sue (2005). Georgian Brighton. Chichester: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 1-86077-342-7.

- Carder, Timothy (1990). The Encyclopaedia of Brighton. Lewes: East Sussex County Libraries. ISBN 0-86147-315-9.

- Dale, Antony (1950). The History and Architecture of Brighton. Brighton: Bredin & Heginbothom Ltd.

- Dale, Antony (1989). Brighton Churches. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00863-8.

- Elleray, D. Robert (2004). Sussex Places of Worship. Worthing: Optimus Books. ISBN 0-9533132-7-1.

- Gilbert, Edmund M. (1954). Brighton: Old Ocean's Bauble. Hassocks: Flare Books. ISBN 0-901759-39-2.

- Musgrave, Clifford (1981). Life in Brighton. Rochester: Rochester Press. ISBN 0-571-09285-3.

- Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). The Buildings of England: Sussex. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071028-0.

- A Guide to the Buildings of Brighton. School of Architecture and Interior Design, Brighton Polytechnic. Macclesfield: McMillan Martin. 1987. ISBN 1-869865-03-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)