Use of nigger in the arts

This article treats the usage of the word nigger (now widely considered a racial slur) in reference to African Americans and others of African or mixed African and other ethnic origin in the art of Western culture and the English language.

Literature

The use of nigger in older literature has become controversial because of the word's modern meaning as a racist insult.

In the title

Our Nig: Sketches from the Life of a Free Black is an autobiographical novel by Harriet E. Wilson, a free Negro herself. It was published in 1859[1] and rediscovered in 1981 by literary scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. It is believed to be the first novel published by an African-American woman on the North American continent.[2][3]

In 1897, Joseph Conrad penned a novella titled The Nigger of the 'Narcissus', whose titular character, James Wait, is a West Indian black sailor on board the merchant ship Narcissus sailing from Bombay to London. In the United States, the novel was first published with the title The Children of the Sea: A Tale of the Forecastle, at the insistence by the publisher, Dodd, Mead and Company, that no one would buy or read a book with the word "nigger" in its title,[4] not because the word was deemed offensive but that a book about a black man would not sell.[5] In 2009, WordBridge Publishing published a new edition titled The N-Word of the Narcissus, which also excised the word "nigger" from the text. According to the publisher, the point was to get rid of the offensive word, which may have led readers to avoid the book, and make it more accessible.[6] Though praised in some quarters, many others denounced the change as censorship.

The writer and photographer Carl Van Vechten took the opposite view to Conrad's publishers when he advised the British novelist Ronald Firbank to change the title of his 1924 novel Sorrow in Sunlight to Prancing Nigger for the American market,[7] and it became very successful there under that title.[8] Van Vechten, a white supporter of the Harlem Renaissance (1920s–30s), then used the word himself in his 1926 novel Nigger Heaven, which provoked controversy in the black community. Of the controversy, Langston Hughes wrote:

No book could possibly be as bad as Nigger Heaven has been painted. And no book has ever been better advertised by those who wished to damn it. Because it was declared obscene, everybody wanted to read it, and I'll venture to say that more Negroes bought it than ever purchased a book by a Negro author. Then, as now, the use of the word nigger by a white was a flashpoint for debates about the relationship between black culture and its white patrons.

Ten Little Niggers was the original title of Agatha Christie's 1939 detective novel in the UK edition, named for a children's counting-out game familiar in England at that date. The U.S. edition, however, was titled And Then There Were None, using "Injuns" instead of "niggers" in the counting-out rhyme. Since the 1980s, the title has been changed to And Then There Were None for all English editions, and the rhyme has been changed to "Ten little soldier boys".[9][10] The novel retains its original title in some other languages. For example, a current Mexican edition is entitled Diez negritos (English: Ten Little Negroes).

Flannery O'Connor uses a black lawn jockey as a symbol in her 1955 short story "The Artificial Nigger". American comedian Dick Gregory used the word in the title of his 1964 autobiography, written during the American Civil Rights Movement. Gregory comments on his choice of title in the book's primary dedication: "if ever you hear the word "nigger" again, remember they are advertising my book.[11] Gil Scott-Heron, the American jazz poet who wrote "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised", released a novel in 1972 entitled '''The Nigger Factory", described as " life on black college campuses".[12] Labi Siffre, the singer-songwriter best known for "(Something Inside) So Strong", entitled his first book of poetry simply Nigger (Xavier Books 1993).

Huckleberry Finn

Mark Twain's novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885) has long been the subject of controversy for its racial content. Huckleberry Finn was the fifth most challenged book during the 1990s, according to the American Library Association.[13] The novel is written from the point of view, and largely in the language, of Huckleberry Finn, an uneducated white boy, who is drifting down the Mississippi River on a raft with an adult escaped slave, Jim. The word "nigger" is used (mostly about Jim) over 200 times.[14][15] Twain's advocates note that the novel is composed in then-contemporary vernacular usage, not racist stereotype, because Jim, the black man, is a sympathetic character.

In 2011, a new edition published by NewSouth Books replaced the word "nigger" with "slave" and also removed the word "injun". The change was spearheaded by Twain scholar Alan Gribben in the hope of "countering the 'pre-emptive censorship'" that results from the book's being removed from school curricula over language concerns.[16][17] The changes sparked outrage from critics Elon James, Alexandra Petrie and Chris Meadows.[18]

British literary usage

.jpg.webp)

Several late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century British literary usages suggest neutral usage. The popular Victorian era entertainment, the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta The Mikado (1885), twice uses the word nigger. In the song As some day it may happen, the executioner, Ko-ko, sings of executing the "nigger serenader and the others of his race", referring to white singers with their faces blacked singing minstrel songs. In the song A more humane Mikado, the Mikado sings of the punishment for older women who dye their hair or wear corsets, to be "Blacked like a nigger/With permanent walnut juice." Both lyrics are usually changed for modern performances.[19]

The word "nigger" appears in children's literature. "How the Leopard Got His Spots", in the Just So Stories (1902) by Rudyard Kipling, tells of an Ethiopian man and a leopard, both originally sand-colored, deciding to camouflage themselves with painted spots, for hunting in tropical forest. The story originally included a scene wherein the leopard (now spotted) asks the Ethiopian man why he does not want spots. In contemporary editions of "How the Leopard Got His Spots", the Ethiopian's original reply ("Oh, plain black's best for a nigger") has been edited to, "Oh, plain black's best for me." The counting rhyme known as "Eenie Meenie Mainee, Mo" has been attested from 1820, with many variants; when Kipling included it as "A Counting-Out Song" in Land and Sea Tales for Scouts and Guides (1923), he gave as its second line, "Catch a nigger by the toe!" This version became widely used for much of the twentieth century; the rhyme is still in use, but the second line now uses "tiger" instead.

The word "nigger" is used by the child characters in some of the Swallows and Amazons series, written in the 1930s by Arthur Ransome, e.g. in referring to how the (white) characters appear in photographic negatives ("Look like niggers to me") in The Big Six, and as a synonym for black pearls in Peter Duck. Editions published by Puffin after Ransome's death changed the word to 'negroes'.

The first Jeeves novel, Thank You, Jeeves (1934), features a minstrel show as a significant plot point. Bertie Wooster, who is trying to learn to play the banjo, is in admiration of their artistry and music. P. G. Wodehouse has the repeated phrase "nigger minstrels" only on the lips of Wooster and his peers; the manservant Jeeves uses the more genteel "Negroes".

In short story "The Basement Room" (1935), by Graham Greene, the (sympathetic) servant character, Baines, tells the admiring boy, son of his employer, of his African British colony service, "You wouldn't believe it now, but I've had forty niggers under me, doing what I told them to". Replying to the boy's question: "Did you ever shoot a nigger?" Bains answers: "I never had any call to shoot. Of course I carried a gun. But you didn't need to treat them bad, that just made them stupid. Why, I loved some of those dammed niggers." The cinematic version, The Fallen Idol (1948), directed by Carol Reed, replaced this usage with "natives".

In Paul Temple (1940) [Track 15][20] by Francis Durbridge the phrase "he worked like a nigger" is used without any apparent further context.

Virginia Woolf, in her 1941 posthumously published novel Between the Acts, wrote "Down amongst the bushes she worked like a nigger." The phrase is not dialogue from one of the characters, nor is it in the context of expressing a point of view of one of the characters.[21] Woolf's usage of racist slurs has been examined in various academic writings.[22]

The Reverend W. V. Awdry's The Railway Series (1945–72) story Henry's Sneeze, originally described soot-covered boys with the phrase "as black as niggers".[23] In 1972, after complaints, the description was edited to "as black as soot", in the subsequent editions.[23] The best-known character in the series is Thomas the Tank Engine (1946).

Music

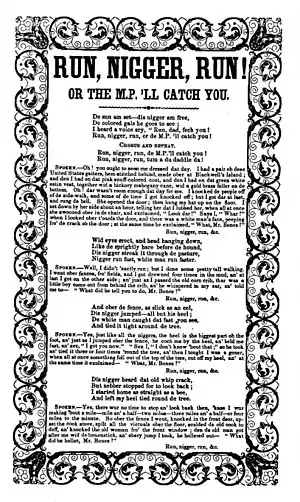

The 19th-century minstrel song "Oh! Susanna" by Stephen Foster had originally been written in four verses. The second verse describes an industrial accident which "kill'd five hundred Nigger" by electrocution.

The Bohemian composer Antonín Dvořák wrote the String Quartet No. 12 in 1893 during his time in the United States. For its presumed association with African-American music, the quartet was referred to until the 1950s with nicknames such as "Negro Quartet" and "Nigger Quartet" before being called the "American Quartet".

The 1932 British song "The Sun Has Got His Hat On" originally included the line "He's been tanning niggers out in Timbuktu" (where "He" is the sun). Modern recordings substitute other lines.

The term white nigger is also used in music, including in Elvis Costello's 1979 song "Oliver's Army".

1960s

The South African song "Ag Pleez Deddy" by Jeremy Taylor, released in 1962, includes in its chorus a mention of "Nigger balls", a type of gobstopper, as one of a series of consumer products coveted by the young white South Africans who are the song's focus. The song was banned by the South African Broadcasting Corporation, but this was because its mixing of English and Afrikaans language was considered to violate the principles of apartheid.[24] In the longer term, the mention of "Nigger balls" became more controversial: when Oxford University Press's A New Book of South African Verse in English was published in 1979, the term "acid-drops" was substituted;[24][25] and when later singing the song in the United States, Taylor substituted "sugar balls".[26]

In the 1960s, record producer J. D. "Jay" Miller published pro-racial segregation music, with the "Reb Rebel" label featuring racist songs by Johnny Rebel and others, demeaning black Americans and the Civil Rights Movement.[27] The country music artist David Allan Coe used the racial terms "redneck", "white trash", and "nigger" in the songs "If That Ain't Country, I'll Kiss Your Ass" and "Nigger Fucker".

Just before their breakout at The Woodstock music festival in 1969, Sly and the Family Stone released their hit album Stand! which contained the song "Don't Call me Nigher, Whitey".[28]

1970s

In 1970 the American band The Last Poets released their debut album of the same name. It features three tracks using the word in their titles: "Run, Nigger", "Wake Up, Niggers", and "Niggers Are Scared of Revolution". The British performance poet Malik Al Nasir claims that his mentor Gil Scott-Heron was inspired to write classic song "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" by the last of these three.[29]

In 1972 John Lennon and Yoko Ono used the word in both the title and in the chorus of their song "Woman Is the Nigger of the World", which was released as both a single and a track on their album "Sometime in New York City."[30]

Mick Jagger used the word in The Rolling Stones' song "Sweet Black Angel" from the 1972 album Exile on Main St.

On Bob Marley and the Wailers' 1973 song "Get Up, Stand Up", Marley can be heard singing the line, "Don't be a nigger in your neighborhood" during the outro.

Stevie Wonder used the word in the album version (but not the single version) of his 1973 song "Living for the City."

Freddie Mercury used the word in Queen's song "The March of the Black Queen" from the 1974 album Queen II.

In 1975 Betty Davis used the word in her song "F.U.N.K."; Bob Dylan used the word in his song "Hurricane".[31]

In 1978 Patti Smith used the word prominently in her song "Rock N Roll Nigger".

In 1979 Elvis Costello used the phrase "White nigger" to refer to Northern Irish people forced to become mercenaries in the song "Oliver's Army".

1980s and 1990s

The punk band the Dead Kennedys used the word in their 1980 song "Holiday in Cambodia" in the line, "Bragging that you know how the niggers feel cold and the slum's got so much soul". The context is a section mocking champagne socialists. Rap groups such as N.W.A (Niggaz with Attitudes) re-popularized the usage in their songs. One of the earliest uses of the word in hip hop was in the song "New York New York" by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five in 1983. Responding to accusations of racism after referring to "niggers" in the lyrics of the 1988 Guns N' Roses song, "One in a Million", Axl Rose stated: "I was pissed off about some black people that were trying to rob me. I wanted to insult those particular black people. I didn't want to support racism."[32]

In 1981, Frank Zappa used the word in his song "You Are What You Is" in his album under the same name.

In 1987, the thrash metal band M.O.D. used the word in their song "Aren't You Hungry?", off their first album U.S.A. for M.O.D..

In 1992, the Swedish crossover band Clawfinger had a hit single with the title Nigger. The lyrics criticized the self-derogatory nature of that word's usage by black people. The controversial song also appeared on their first album Deaf Dumb Blind, in 1992 and on their demos from 1990.

The 1993 song from A Tribe Called Quest "Sucka Nigga" off their album Midnight Marauders addresses the rising usage of the word in Hip Hop at the time.

While not directly used in the lyrics, the American metal band Eyehategod released a song titled "White Nigger" in 1993.[33]

21st century

Since the 2010s the word nigger has been used with increasing frequency[34] by African Americans amongst themselves or in self-expression, the most common swear word in hip hop music lyrics.[35] As a result, it is a word that is heard daily by millions of all races worldwide who listen to uncensored hip hop and other music genres, while being socially unacceptable for anyone but African Americans to utter. Ta-Nehisi Coates has suggested that it continues to be unacceptable for people who are not of African ancestry to utter the word nigger while singing or rapping along to hip-hop, and that by being so restrained it gives White Americans (specifically) a taste of what it's like to not be entitled to "do anything they please, anywhere". Counterpoint to this standpoint is the open question of whether daily, frequent exposure by non-Black Americans to African Americans using the word will inevitably lead to a dilution of the extremely negative perception of the word among the majority of non-Black Americans that currently consider its use unacceptable and shocking.[36]

Sardonic grindcore band Anal Cunt released a song titled "Beating Up Niggers that Sell Fake Crack", which also contains references to the word "nigger" in the lyrics. The song appeared part of the band's final album Wearing Out Our Welcome, released shortly after the death of the band's frontman Seth Putnam.[37]

Theater

The musical Show Boat, which subverts anti-miscegenation laws, from 1927 until 1946 features the word "nigger" as originally integral to the lyrics of "Ol' Man River" and "Cotton Blossom"; although deleted from the cinema versions, it is included in the 1988 EMI recording of the original score. Musical theatre historian Miles Kreuger and conductor John McGlinn propose that the word was not an insult, but a blunt illustration of how white people then perceived black people.

Bernardine Evaristo used the word as the title her first play as a student, which the then head of Rose Bruford College said "was the best piece of theatre he'd ever seen". She went on to found the Theatre of Black Women and in 2020 became President of her alm mater. Evaristo recalled her student production on Desert Island Discs decades later:

- It was really short and it was basically an explosion of rage. It was called the N word. And I jumped onto the stage and I shouted that word out really loudly. And then I say something like 'Too black, not black enough, too white, not white enough' and then some other things and then jump off the stage. So it was really short. And it was probably very powerful. He probably hadn't seen anything like it before. It really was a very vicious word then. And I was basically saying, this is how I'm seen. This is what I might be called. But where do I stand because I'm a mixed race person. Not a very sophisticated piece of theatre, but punchy.[38]

The Moore's Ford lynchings, also known as the 1946 Georgia lynching, has been commemorated since 2005 with a yearly re-enactment. According to a volunteer actor playing one of the victims, this living memorial "consist[s] largely of older white men calling him "nigger," tying a noose around his neck, and pretending to shoot him repeatedly"[39]

Cinema

One of Horace Ové's first films was Baldwin's Nigger (1968), in which two African Americans, novelist James Baldwin and comedian Dick Gregory, discuss Black experience and identity in Britain and the United States.[40] Filmed at the West Indian Students' Centre in London, the film documents a lecture by Baldwin and a question-and-answer session with the audience.[41][42]

Mel Brooks' 1974 satirical Western film Blazing Saddles used the term repeatedly. In The Kentucky Fried Movie (1977), the sequence titled "Danger Seekers" features a stuntman performing the dangerous act of shouting "Niggers!" at a group of black people, then fleeing when they take chase.

Stanley Kubrick's critically acclaimed 1987 war film Full Metal Jacket depicts black and white U.S. Marines enduring boot camp and later fighting together in Vietnam. "Nigger" is used by soldiers of both races in jokes and as expressions of bravado ("put a nigger behind the trigger", says the Black Corporal "Eightball"), with racial differences among the men seen as secondary to their shared exposure to the dangers of combat: white Gunnery Sergeant Hartman says, "There is no racial bigotry here. I do not look down on niggers, kikes, wops or greasers. Here you are all equally worthless."

Gayniggers from Outer Space, a 1992 English-language Danish short blaxploitation parody, features black homosexual male aliens who commit gendercide to free the men of Earth from female oppression. Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995) featured a scene where villain Simon Gruber requires New York City Police Department Lt. John McClane to wear a sandwich board reading "I hate niggers" while standing on a street corner in predominantly-black Harlem, resulting in McClane meeting Zeus Carver, as Carver rescues McClane from being attacked by neighborhood toughs.

American filmmaker Quentin Tarantino has been criticized[43] for the heavy usage of the word nigger in his films, especially Jackie Brown (1997), where the word is used 38 times[44] and Django Unchained (2012), used 110 times.[45]

The Dam Busters

During World War II, a dog named Nigger, a black Labrador belonged to Royal Air Force Wing Commander Guy Gibson. In 1943, Gibson led the successful Operation Chastise attack on dams in Nazi Germany. The dog's name was used as a single codeword whose transmission conveyed that the Möhne dam had been breached. In Michael Anderson's 1955 film The Dam Busters, based on the raid, the dog was portrayed in several scenes; his name and the codeword were mentioned several times. Some scenes were sampled in Alan Parker's 1982 film Pink Floyd – The Wall.[46]

In 1999, British television network ITV broadcast a censored version with each of the twelve[47] utterances of nigger deleted. Replying to complaints, ITV blamed regional broadcaster London Weekend Television, which, in turn, singled out a junior employee as the unauthorised censor. In June 2001, when ITV re-broadcast the censored version of The Dam Busters, Index on Censorship criticised it as "unnecessary and ridiculous" censorship breaking the continuity of the film and the story.[48] In January 2012, the film was shown uncensored on ITV4, but with a warning at the start that the film contained racial terms from the historical period which some people could find offensive. Versions edited for US television have the dog's name altered to "Trigger".[47]

In 2008, New Zealand filmmaker Peter Jackson announced his intention to spearhead a remake. Screenwriter Stephen Fry said there was "no question in America that you could ever have a dog called the N-word". In the unrealized remake, the dog was to be renamed "Digger".[49]

Television

The word nigger has been used in several episodes of television programs. A well-known example is the eleventh season premiere of South Park, "With Apologies to Jesse Jackson", in which Randy Marsh says nigger on Wheel of Fortune, which triggers public humiliation and ostracism. Despite criticism from the Parents Television Council, many, including African Americans, have praised the episode for its humorous message of how it feels to be called a nigger.

Stand-up comedy

Some stand-up comedians have broached the subject. This was done in 1996 by Chris Rock in his "Niggas vs. Black People" routine.[50] Richard Pryor used the word extensively before pledging to remove it from his lexicon, having had a change of heart during a trip to Africa.[51][52] Comedian Dick Gregory titled his 1964 memoir "Nigger: An Autobiography by Dick Gregory".

References

- Wilson, Harriet E. (2004) [1859]. Our Nig: Sketches From The Life Of A Free Black. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4000-3120-6. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- Interview with Henry Louis Gates (mp3) Archived May 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Gates and a literary critic discuss Our Nig, Wired for Books

- Our Nig: Sketches from the Life of a Free Black, Geo. C. Rand and Avery, 1859.

- Orr, Leonard (1999). A Joseph Conrad Companion. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-29289-7.

- "Children of the Sea|The – Sumner & Stillman". Sumnerandstillman.com. December 1, 2006. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- Joseph Conrad (December 2009). The N-word of the Narcissus. Foreword by Ruben Alvarado. WorldBridge. ISBN 9789076660110.

- Bernard, Emily (2012). Carl Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance. Yale University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780300183290.

- Jocelyn Brooke. "Novels of Ronald Firbank by Jocelyn Brooke". ourcivilisation.com.

- Peers, C; Spurrier A & Sturgeon J (1999). Collins Crime Club – A checklist of First Editions (2nd ed.). Dragonby Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-871122-13-8.

- Pendergast, Bruce (2004). Everyman's Guide To The Mysteries Of Agatha Christie. Victoria, BC: Trafford Publishing. p. 393. ISBN 978-1-4120-2304-7.

- "Dick Gregory Global Watch - About Dick Gregory". Dickgregory.com. 1932-10-12. Archived from the original on 2007-06-17. Retrieved 2013-10-08.

- "'Gil Scott-Heron saved my life'". the Guardian. 2011-06-19. Retrieved 2022-10-18.

- "100 most frequently challenged books: 1990–1999". ala.org. March 27, 2013.

- "Adventures Of Huckleberry Finn". The Complete Works of Mark Twain. Archived from the original on September 9, 2006. Retrieved March 12, 2006.

- "Academic Resources: Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word". Random House. Archived from the original on January 22, 2007. Retrieved March 13, 2006. Alt URL

- "New Huckleberry Finn edition censors 'n-word'". the Guardian. 5 January 2011.

- Twain, Mark (January 7, 2011). "'The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn' – Removing the N Word from Huck Finn: Top 10 Censored Books". TIME. Archived from the original on January 10, 2011. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- The Christian Science Monitor (January 5, 2011). "The 'n'-word gone from Huck Finn – what would Mark Twain say?". The Christian Science Monitor.

- Michael Sragow (December 23, 1999). "The roar of the greasepaint, the smell of the crowd". Archived from the original on February 14, 2005. Retrieved March 13, 2006.

- Paul Temple: The Complete Radio Collection: Volume One.

- Woolf, Virginia (1949). Between the Acts. Rome: Albatross. p. 175.

- Lee, Hermione: "Virginia Woolf and Offence," in The Art of Literary Biography, Oxford Scholarship Online: October 2011; reviewed by McManus, Patricia: "The "Offensiveness" of Virginia Woolf: From a Moral to a Political Reading" in Woolf Studies Annual, vol. 14, Annual 2008.

- Sibley, Brian (1995). The Thomas the Tank Engine Man. London: Heinemann. pp. 272–5. ISBN 978-0-434-96909-8.

- "Ag pleez Deddy won't you take us to the Equality Court". Sunday Times. 18 October 2009.

- Butler, Guy; Mann, Chris, eds. (1979). A New Book of South African Verse in English. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. pp. 222–223. ISBN 978-0-19-570141-8.

- Taylor, Jeremy (2005). "Ag Pleez Deddy". River Forest, Illinois. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 13 June 2020 – via YouTube.

- John Broven, South to Louisiana: The Music of the Cajun Bayous. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican, 1983, p. 252f.

- admin. "Stand!". The Official Sly Stone Site. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- "'Gil Scott-Heron saved my life'". the Guardian. 2011-06-19. Retrieved 2022-10-18.

- Duston, Anne. "Lennon, Ono 45 Controversial" Billboard June 17, 1972: 65

- Listen to the lyric video of the song on YouTube

- MNeely, Kim (April 2, 1992). "Axl Rose: The RS Interview". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- Jimmy Bower guitarist of Eyehategod interview

- Sheinin, Dave (November 9, 2014). "Redefining the Word". Washington Post. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- "Profanity in lyrics: most used swear words and their usage by popular genres". Musixmatch. December 16, 2015. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- Bain, Marc (November 13, 2017). "Ta-Nehisi Coates Gently Explains Why White People Can't Rap the N-Word". Quartz. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- "Beating Up Niggers That Sell Fake Crack". allmusic.com.

- "BBC Radio 4 - Desert Island Discs - 10 things we learned from Bernardine Evaristo's Desert Island Discs".

- Baker, Peter C. (November 2, 2016). "A lynching in Georgia: the living memorial to America's history of racist violence". The Guardian. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- Horace Ové biography, BFI Screenonline.

- "Baldwin's Nigger (1968)" at IMDb.

- "Baldwin's Nigger (1969)", BFI Screenonline.

- Child, Ben (October 13, 2005). "Quentin Tarantino tells 'black critics' his race is irrelevant". The Guardian.

- "Review Django Unchained- Spaghetti southern style". The Boston Phoenix. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- "Django Unchained – Audio Review". Spill.com. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- "Analysis of the symbols used within the film, "Pink Floyd's The Wall"". Thewallanalysis.com. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- Chapman, Paul (May 6, 2009). "Fur flies over racist name of Dambuster's dog". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ITV attacked over Dam Busters censorship, The Guardian, June 11, 2001

- "Dam Busters dog renamed for movie remake". BBC News. June 10, 2011.

- Julious, Britt (June 24, 2015). "The N-word might be part of pop culture, but it still makes me cringe". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- Danahy, Anne (April 19, 2019). "Take Note: Elizabeth Pryor On The 'N-Word'". radio.wpsu.org. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- Logan, Brian (January 11, 2015). "Richard Pryor – the patron saint of standup as truth-telling". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved July 3, 2019.