Ushrusaniyya

The Ushrusaniyya (Arabic: ٱلْأُشْرُوسَنْيَّة, romanized: al-Ushrūsaniyya) were a regiment in the regular army of the Abbasid Caliphate. Formed in the early ninth century A.D., the unit consisted of soldiers who were originally from the region of Ushrusana in Transoxiana. The Ushrusaniyya initially served under the prominent general al-Afshin, but they remained active after his downfall, and are frequently mentioned during the period known as the Anarchy at Samarra.

Background

Ushrusana was a frontier province in Central Asia, bordering the lands of Islam during the Umayyad and early Abbasid caliphates. It was situated between the districts of Samarkand in the west and Khujand to the east, and was somewhat south of the Syr Darya River. As a result of its location, several roads ran through it, making the province a frequent stop for travelers. The terrain of the country consisted of a mixture of plains and mountains; some districts of Ushrusana had towns, but overall the region was little urbanized. The primary city was Bunjikath, which was often referred to as the City of Ushrusana.[1]

Prior to the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana in the early 8th century, Ushrusana was ruled by what was probably an Iranian dynasty, whose princes were known by the title of afshīn.[2] Over the course of the 8th century Ushrusana was at times nominally subject to the Caliphate, but it remained effectively independent. Several Umayyad governors conducted raids into the country and received tribute from its rulers, but permanent conquest was not achieved by them.[3] After the Abbasids came to power in 750, the princes of Ushrusana made submissions to the caliphs during the reigns of al-Mahdi (r. 775–785) and Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809), but these appear to have been nominal acts[4] and the people of the region continued to resist Muslim rule.[5]

Ushrusana was more firmly brought under Abbasid control following a quarrel that broke out within the ruling dynasty, during the caliphate of al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833). In 822, a Muslim army under Ahmad ibn Abi Khalid al-Ahwal conquered Ushrusana and captured its ruler Kawus ibn Kharakhuruh; he was sent to Baghdad, where he submitted to the caliph and converted to Islam.[6] From this point on, Ushrusana was generally considered to be part of the Abbasid state, although the afshīns were allowed to retain their control over the country as subjects of the caliph.[7]

Kawus was succeeded by his son Khaydhar, who had assisted Ahmad ibn Abi Khalid in his campaign against Ushrusana. Khaydhar, who is usually referred to in the sources simply as al-Afshin,[8] decided to enter the service of the Abbasids and made his way to al-Ma'mun's court. There he embarked on a military career, and became a commander in the caliphal army.[9] With al-Afshin came a number of his followers, a number of whom were fellow natives of Ushrusana. These men were integrated into the army and, serving under their prince, became known as the Ushrusaniyya.[10]

The Ushrusaniyya under al-Afshin

The formation of the Ushrusaniyya regiment was part of a general policy initiated by al-Ma'mun and expanded by al-Mu'tasim (r. 833–842) to recruit soldiers from the various frontier districts of Transoxiana. As a result, the Ushrusaniyya were joined by other newly formed regiments from Central Asia, such as the Turks, the Faraghina, and the Ishtakhaniyya. These soldiers soon formed the majority of the caliphs' guard and replaced the older Khurasani Abna' as the backbone of the army. For the next several decades, these units collectively remained the dominant force in the caliphal military, both in Baghdad and, after 836, in Samarra.[11]

After joining the caliphal court, al-Afshin quickly became one of the leading figures in the Abbasid military establishment.[12] During the caliphate of al-Ma'mun, he was sent to Barqa and, in 831, to Egypt, in order to suppress rebel activity in those provinces. After al-Mu'tasim became caliph, he was given a major command as the leader of the war against Babak al-Khurrami in Adharbayjan, and after a two-year campaign (835–837) he succeeded in destroying the rebellion and capturing its leader. Following this, he was put in charge of part of the Muslim army during al-Mu'tasim's 838 expedition against the Byzantines, and he played a leading role during the siege of Amorium.[13] The exact composition of his forces during these campaigns is unknown, but it appears that both Ushrusani and non-Ushrusani officers were serving under him by the mid-830s.[14]

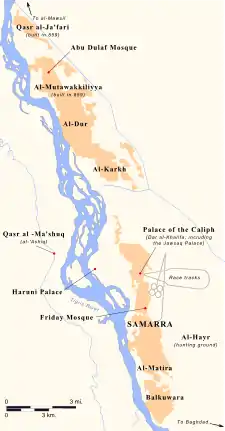

In 836 the Ushrusaniyya, together with the rest of the central army, were transferred to the new capital city of Samarra. They and other units attached to al-Afshin were granted allotments in the cantonment of al-Matira, in the southern part of the city.[15] Here al-Afshin built a palace for himself;[16] on the caliph's orders, he also constructed a small market for his followers, together with baths and mosques.[17]

Numbers and equipment

No specific figures are provided in regards to the overall strength of the Ushrusaniyya in Samarra. Based on the frequent references to them in the sources, however, it is likely that they were one of the larger regiments in the capital.[18] On the other hand, they were certainly outnumbered by the Turks, and probably by the Faraghina as well.[19] The sources also suggest that not all of the troops under the command of al-Afshin were Ushrusaniyya,[14] and that al-Matira was partly populated by non-Ushrusanians.[17] Ushrusana itself was not a large country, and its population may not have been large enough to supply many soldiers.[15]

Modern estimates on the overall size and composition of the Samarran military vary widely, but the Ushrusaniyya are generally considered to have made up only a small portion of the army. Historian Helmut Töllner, for example, speculated that there were 20,000 to 30,000 troops in Samarra; of these, half were Turks,[20] and the Ushrusaniyya would have constituted only a fraction of the remainder. Archaeologist Derek Kennet, after surveying the remains of the military cantonments in Samarra, estimated that al-Matria was home to 11,847 soldiers (Ushrusaniyya and non-Ushrusaniyya alike) during the reign of al-Mu'tasim, out of a total army size of 94,353;[21] other historians, however, have considered these numbers to be too large.[22] Hugh N. Kennedy, relying on figures provided in the literary sources, believed that there may have been around 5,000 non-Turkish Transoxianans, including Ushrusaniyya, in the central army.[23]

The equipment used by the Ushrusaniyya in combat is described at some length in a passage by the chronicler al-Tabari. During a riot in Samarra, in which the Ushrusaniyya were sent out to restore order, the troops fought the rioters with multiple weapons, firing arrows (nushshāb) into the hostile crowd and engaging them with swords (suyūf). For defense, they were equipped with shields (durūʿ) and wore coats of mail (jawāshan). They were also provided with mounts (dawābb), but it is not specified whether these were meant to be ridden in battle or simply used for transport.[24]

Subsequent history

Al-Afshin's career came to an end when he was imprisoned on allegations of treason and apostasy in 841, and this likely resulted in a decline in the importance of the Ushrusaniyya.[25] Al-Ya'qubi notes that after al-Afshin's death, the Turkish commander Wasif al-Turki and his followers took up residence in al-Matira during the caliphate of al-Wathiq (r. 842–847),[26] and it is possible that the Ushrusaniyya were displaced from that area and forced to settle elsewhere in the city.[27] The regiment survived, however, and continued to be used in military campaigns. In 847, for example, they participated in Bugha al-Kabir's expedition against the disorderly Banu Numayr in western Arabia, during which they were under the command al-Afshin's former lieutenant Wajin al-Ushrusani.[28]

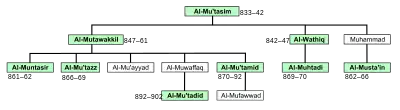

Following the assassination of the caliph al-Mutawakkil in December 861, the caliphate entered a period of instability, known as the Anarchy at Samarra.[29] During this period, the Ushrusaniyya, along with the other military regiments, played a prominent part in the affairs of the capital. Al-Mutawakkil's son al-Muntasir (r. 861–862), who was complicit in his father's death, had sought to make allies of the Ushrusaniyya in the days leading up to the murder, and many of them threw their support behind him.[30] After al-Muntasir died in June 862, the Ushrusaniyya, together with the Turks and Maghariba, agreed to the selection of al-Musta'in as al-Muntasir's successor, and they were present during an inauguration ceremony for the new caliph. When riots broke out in the capital in favor of al-Musta'in's rival al-Mu'tazz, they were deployed to help suppress the dissidents, but suffered heavy casualties during the fighting.[31]

During the civil war which broke out between al-Musta'in and al-Mu'tazz in 865, a large continent of Ushrusaniyya was present in Baghdad to fight for al-Musta'in; these were placed under the command of al-Afshin's son al-Hasan.[32] Other Ushrusani officers, also on the side of al-Musta'in, were assigned to various commands, such as escorting revenue shipments to Baghdad and guarding the city suburbs.[33] After the war ended in early 866 in favor of al-Mu'tazz, the Ushrusaniyya returned to Samarra, and over the next several years they occasionally participated in riots in the city.[34]

In June 870, the Ushrusaniyya rallied to defend the caliph al-Muhtadi (r. 869–870) when the Turks under Musa ibn Bugha al-Kabir revolted, but they were defeated and the caliph was killed.[35] This event seems to have resulted in the decline of the regiment; after this point, it disappears from the sources.[36]

Notes

- Le Strange, pp. 474-75; Kramers, pp. 924-25; Bosworth, p. 589

- Kramers, p. 925; Bosworth, pp. 589-90; Barthold and Gibb, p. 241

- Kramers, p. 925; al-Tabari, v. 24: p. 173; v. 25: p. 148; v. 26: p. 31; al-Baladhuri, pp. 190, 203

- Al-Ya'qubi, Historiae, p. 479; al-Tabari, v. 30: p. 143

- For example, joining Rafi' ibn Layth's rebellion and reneging on tribute agreements: al-Ya'qubi, Historiae, p. 528; al-Baladhuri, pp. 203-04

- Bosworth, p. 590; Kramers, p. 925; Kennedy, p. 125; al-Baladhuri, pp. 204-05; al-Tabari, v. 32: pp. 107, 135

- Kramers, p. 925. The dynasty remained in power until 893, when Ushrusana became a directly-administered province of the Samanids.

- Barthold and Gibb, p. 241

- Bosworth, p. 590; Kennedy, p. 125

- Kennedy, p. 125; Gordon, p. 43; Northedge, p. 169

- Kennedy, pp. 118-22, 124-25; Gordon, pp. 15 ff.; al-Baladhuri, p. 205

- Kennedy, p. 125

- Bosworth, p. 590

- Gordon, p. 43

- Northedge, p. 169

- Al-Tabari, v. 33: p. 200 & n. 581

- al-Ya'qubi, Buldan, p. 259

- Gordon, p. 37

- Kennedy, pp. 126-27; Gordon, p. 37

- Töllner, p. 48

- Kennet, p. 177

- Gordon, pp. 72-73; Kennedy, pp. 205-07

- Kennedy, pp. 127-28

- Al-Tabari, v. 35: p. 4

- Crone, p. 319

- Al-Ya'qubi, Buldan, pp. 264-65

- Northedge, pp. 169-70, interpreting al-Ya'qubi's reference (Buldan, p. 263) that some of the Ushrusaniyya officers were located in the Shari' al-Hayr al-Jadid. Alternatively, Wasif may have assumed responsibility for the Ushrusaniyya in al-Matira, resulting in their subordination to Turkish command; Gordon, p. 78

- Al-Tabari, v. 34: p. 50. The text reads "al-Ushrusaniyyah al-Ishtikhaniyyah;" in Kraemer's opinion, "perhaps the word 'and'" should be inserted between the two names. Kraemer, n. 186

- On this period, see Gordon, pp. 90 ff.

- Al-Mas'udi, v. 7: p. 273

- Al-Tabari, v. 35: pp. 1-5

- Al-Tabari, v. 35: p. 43

- Al-Tabari, v. 35: pp. 58, 92

- Al-Tabari, v. 35: p. 146

- Al-Tabari, v. 36: pp. 93, 107

- For example al-Tabari, Index: p. 79. Kennedy, p. 150, speculates that the Ushrusaniyya may have been downgraded after Abu Ahmad al-Muwaffaq became commander-in-chief of the army during the caliphate of al-Mu'tamid (r. 870-892).

References

- Al-Baladhuri, Ahmad ibn Jabir. The Origins of the Islamic State, Part II. Trans. Francis Clark Murgotten. New York: Columbia University, 1924.

- Al-Bili, 'Osman Sayyid Ahmad Isma'il. Prelude to the Generals: A Study of Some Aspects of the Reign of the Eighth 'Abbasid Caliph, Al-Mu'tasim Bi-Allah (218-227 AH/833-842 AD). Reading: Ithaca Press, 2001. ISBN 0-86372-277-6

- Barthold, W. & Gibb, H.A.R. (1960). "Afshin". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume I: A–B (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. OCLC 495469456.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund. "Afsin." Encyclopaedia Iranica, Volume I. Ed. Ehsan Yarshater. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1985. ISBN 0-7100-9098-6

- Crone, Patricia. "The Early Islamic World." War and Society in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. Eds. Kurt Raaflaub and Nathan Rosenstein. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-674-94660-X

- Ibn al-Athir, 'Izz al-Din. Al-Kamil fi al-Tarikh. 6th ed. Beirut: Dar Sader, 1995.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25093-5.

- Kennet, Derek. "The Form of the Military Cantonments at Samarra, the Organisation of the Abbasid Army." A Medieval Islamic City Reconsidered: an Interdisciplinary Approach to Samarra. Ed. Chase F. Robinson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-197-28024-2

- Kraemer, Joel L., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXIV: Incipient Decline: The Caliphates of al-Wāthiq, al-Mutawakkil and al-Muntaṣir, A.D. 841–863/A.H. 227–248. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-874-4.

- Kramers, J.H. (2000). "Usrushana". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume X: T–U (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Gordon, Matthew S. (2001). The Breaking of a Thousand Swords: A History of the Turkish Military of Samarra (A.H. 200–275/815–889 C.E.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-4795-2.

- Le Strange, Guy (1905). The Lands of the Eastern Caliphate: Mesopotamia, Persia, and Central Asia, from the Moslem Conquest to the Time of Timur. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc. OCLC 1044046.

- Al-Mas'udi, Ali ibn al-Husain. Les Prairies D'Or. Ed. and Trans. Charles Barbier de Meynard and Abel Pavet de Courteille. 9 vols. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1861–1917.

- Northedge, Alastair. The Historical Topography of Samarra. London: The British School of Archeology in Iraq, 2005. ISBN 0-903472-17-1

- Al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir. The History of al-Tabari. Ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater. 40 vols. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1985–2007.

- Töllner, Helmut. Die türkischen Garden am Kalifenhof von Samarra, ihre Entstehung und Machtergreifung bis zum Kalifat al-Mu'tadids. Bonn: Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, 1971.

- Al-Ya'qubi, Ahmad ibn Abu Ya'qub. Historiae, Vol. 2. Ed. M. Th. Houtsma. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1883.

- Al-Ya'qubi, Ahmad ibn Abu Ya'qub. Kitab al-Buldan. Ed. M.J. de Goeje. 2nd ed. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1892.