Frank Coe (government official)

Virginius Frank Coe (1907 – June 2, 1980) was a United States government official who was identified by Soviet defectors Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers as being an underground member of the Communist Party[1] and as belonging to the Soviet spy group known as the Silvermaster ring.

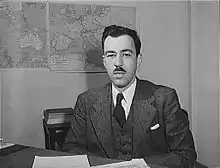

Virginius Frank Coe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1907 Richmond, Virginia, United States |

| Died | June 2, 1980 (aged 73) |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago Johns Hopkins University |

Background

Born in 1907 in Richmond, Virginia, he attended public schools in Tennessee, Alabama, and Chicago. He attended the University of Chicago, earning his bachelor of philosophy in 1926 and continuing graduate work into 1928.

Career

From 1928 to 1930, he was a member of the staff of the Johns Hopkins University Institute of Law, returning to the University of Chicago as a research assistant and to write his thesis from 1930 to 1933. From 1933 to 1934, he was a member of the staff of the Brookings Institution.

Government service

In the summer of 1934, he was a consultant in the Office of the Secretary of the Treasury Department; in the summer of 1936 and spring-summer 1939, he was again a consultant at the Treasury. From the autumn of 1934 until the spring of 1939, he taught economics at the University of Toronto, remaining a member of its staff on leave for several years thereafter (in his testimony, Coe says "4, 5, or 6 years"). Beginning in 1939, he worked adviser to Paul McNutt, then head of the Federal Security Agency, and in 1940 as assistant to Leon Henderson in the Office of Price Administration (then known as the National Defense Council).

Late in 1940, he returned to the Treasury Department as an assistant director of monetary research, where he stayed for about a year, during which he was special assistant to the United States Ambassador in England. In 1942, he became Executive Secretary of the Joint War Production Committee of the United States and Canada[2][3] and an assistant to the Executive Director of the Board of Economic Warfare (later renamed the Foreign Economic Administration). In late 1944/early 1945, Coe was named Director of the Division of Monetary Research in the Treasury Department, serving as technical secretary at the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in 1944, he accepted a position as Secretary of the International Monetary Fund in 1946, his successor at Treasury being Harold Glasser.[4]

Coe resigned from the Fund in December 1952 after public calls were made by Congress for his ouster.[5] The IMF announced his resignation on December 3, 1952.[6]

Allegations and evidence of espionage

The evidence against Coe stems from his being named by two defected spies and ex post examinations of his career.

In 1939, former Communist underground courier Whittaker Chambers named Coe to then-Assistant Secretary of State Adolf Berle as a communist sympathizer who was providing information to the Ware group.[7]

In 1948, former NKVD courier Elizabeth Bentley, testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee, mentioned Coe, whom she remembered as one of several important Treasury officials who passed on information to Silvermaster.[8][9]

Called before the HUAC (chaired by Congressman Karl Mundt), Coe denied under oath having ever been a member of the Communist Party USA. Subsequently, he was questioned intensely in the IMF about his activities, but he was not sanctioned or removed from his duties.[10] In late 1952, he was called before a Grand Jury in New York (presided over by Senator Herbert O'Conor) and then before the McCarran Committee on December 1, 1952, both of which were investigating alleged Communist affiliations of U.S. citizens working for the United Nations and other international organizations. On the latter occasion, he declined to answer the question of whether he was a member of the Communist Party on Fifth Amendment grounds, citing the example of Alger Hiss's conviction for perjury.

His final appearance before McCarthy's Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (PSI) came on June 5 and 8, 1953, chaired by then Senator Karl Mundt.

Nominally, the investigation was into interference with negotiations to devalue the Austrian schilling in November 1949 as the Soviets had apparently been profiting from the black market. U.S. officials with the European Cooperation Administration (the Marshall Plan aid agency) reported that a command came via a tickertape telecon to break off negotiations at the last minute. The telecon, which was with an anonymous person at the State Department, cited Coe in his capacity as Secretary of the IMF as the source of the order. (In truth, the devaluation had been discussed by and was supported by the Executive Board of the IMF.)

The PSI ascertained that Coe could not have been the source of the communication as he was in the Middle East at the time,[11] and quickly turned to investigating Coe's alleged Communist activities. Coe, who consulted constantly with his lawyer Milton S. Friedman, maintained his Fifth-Amendment plea, stating at one point that he did not want to see the blacklist extended to include those who had helped him in his search for work.[12]

The subsequent report of the Senate Sub-Committee on Internal Security stated: "Coe refused to answer, on the grounds that the answers might incriminate him, all questions as to whether he was a Communist, whether he was engaged in subversive activities, or whether he was presently a member of a Soviet espionage ring. He refused for the same reason to answer whether he was a member of an espionage ring while Technical Secretary of the Bretton Woods Conference, whether he ever had had access to confidential Government information or security information, whether he had been associated with the Institute of Pacific Relations, or with individuals named on a long list of people associated with that organization.[13]

Later career

Coe was Blacklisted, the US denied his passport (in late 1949) and prevented Coe from traveling to neighboring countries (June 1953) due to his ties to Soviet espionage. Coe sought work abroad, eventually finding a sponsor in the People's Republic of China, where he joined a circle of expatriates working with the government. Frank changed his name to Ke Fulan and was one of the only foreigners ever entrusted to work in the highly secretive and xenophobic International Liaison Department of the Chinese Communist Party, overseeing overt relations with Maoist Parties around the world and also covert foreign operations as well. He became close to the ILD's de facto head Kang Sheng, who frequently invited Coe to his Qing-era mansion, to look over his vast collection of priceless Chinese Arts and Antiques, most of which had been looted from wealthy families, museums, and palaces during the Communist takeover and later during the Cultural Revolution. Although his activities in the ILD remain unclear, Coe's value to his superiors was evidently substantial, so much so that Kang, in an extremely uncharacteristic act, shielded Coe from being purged during the Cultural Revolution, even allowing him to stay in his residence to protect him from the Red Guards. Coe was one of the only people, both Chinese or Foreign, who was ever protected in such a manner by Kang.[14] In 1962, he was joined by Solomon Adler in the circle.[15] Coe participated in Mao's disastrous Great Leap Forward, a plan for the rapid industrialization and modernization of China, which in fact resulted in millions of deaths. Coe sought works included articles justifying the Rectification campaign.[16][17]

Personal life and death

Coe married Ruth Coe, who lived with him in China.[18]

Frank Coe died age 73 on June 2, 1980, in Beijing, China.[19] The New China News Agency listed the cause of his death as a pulmonary embolism and indicated that government officials visited him often during his illness. His brother indicated that he had undergone surgery for cancer eight months earlier.[20]

Legacy

Regarding his policy actions, it is often mentioned that Coe, together with Assistant Treasury Secretary Harry Dexter White and Treasury economist Solomon Adler, opposed President Franklin Roosevelt's gold loan program of $200 million to help the Nationalist Chinese Government stabilize its currency in 1943. However, White's documents indicate while he favored giving economic assistance, he had concerns that cash assistance might be misused or fall into enemy hands.[21]

Arlington Hall cryptographers identified the Soviet agent designated "Peak" in the Venona project as "possibly" Coe, but there is no clear reason for the identification. (One secondary source suggests it was because there was no additional information on Peak.[15]) The decrypt in question reports that five reels of Peak's documents concerning U.S.-British Lend-Lease negotiations were en route to Moscow.[22]

A 1999 investigation into the KGB archives claims that files show Coe to have been a Soviet agent.[23] However, the authors do not quote or reproduce the documents in question and at least one scholar argues that their testimony should be suspended until the primary sources become available.[15]

Bibliography

- Byron, John (1992). The Claws of the Dragon: Kang Sheng (First U.S. ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671797166.

References

- Harvey E. Klehr and Ronald Radosh, The Amerasia Spy Case: Prelude to McCarthyism (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1996) ISBN 0-8078-2245-0, p. 21

- History of the Joint War Production Committee, United States and Canada. Joint War Production Committee, United States and Canada. 1945. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- Federal Records of World War II. GSA - NARA. 1951. pp. 1046-7 (United States-Canadian Agencies - Joint War Production Committee, United States and Canada. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- His position as Secretary was often misunderstood by McCarthy and other Members of Congress to indicate that he had some say in policy. The Secretary's main duties, as Coe testified in 1953, are presiding over Board meetings, preparing the minutes, and distributing documents appropriately. See http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/bl/rr03.htm.

- "National Affairs: A Cast of Characters". Time. November 23, 1953. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

Virginius Frank Coe, 46, first cited by Chambers in 1939, was technical secretary of the Bretton Woods Monetary Conference in 1944, became secretary of Harry D. White's prize product, the International Monetary Fund, and was not dismissed from this $20,000-a-year job until December 1952 —shortly after he refused to answer congressional questions.

- Belair, Jr., Felix. "WORLD FUND OUSTS AIDE WHO BALKED AT RED, SPY QUERIES; Coe Quits on Request -- House Unit Looks Into Jury's Charge U. N. Inquiry Was Hampered JUSTICE AGENCY ACCUSED Lie Orders Employes to Give Replies on Alleged Subversive Activities or Lose Jobs COE IS DISMISSED BY MONETARY FUND", The New York Times, December 4, 1952. Accessed July 1, 2008. "The International Monetary Fund announced today the dismissal of its secretary, Frank Coe, who refused last Monday to tell Senate investigators in New York whether he was now or had ever been a Communist or subversive agent taking orders from Communists."

- Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. Random House. p. 468. ISBN 0-89526-571-0.

- Gabrick, Robert, and Klehr, Harvey, Communism, Espionage, and the Cold War, Los Angeles: UCLA Press, p.15

- "National Affairs: Man of Bretton Woods". Time. 15 December 1952. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- United States Congress. Senate. Austrian incident. Hearings before the Permanent subcommittee on investigations of the Committee on government operations, United States Senate, 83d Cong., 1st sess., pursuant to S. Res. 40 a resolution authorizing the Committee on government operations to employ temporary additional personnel and increasing the limit of expenditures. May 29, June 5 and 8, 1953 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1953); J. Keith Horsefield, The International Monetary Fund, 1945-1965 (Washington: International Monetary Fund), vol. 1, pp. 339-40

- Testimony from H. Merle Cochran, Acting Managing Director, IMF, in Austrian Incident, op. cit., p. 71

- Austrian Incident, op. cit., p. 65.

- (Activities of United States Citizens Employed by the United Nations, report of Senate Sub-Committee on Internal Security, Jan. 2, 1953, p.7; also see hearings and report of this Sub-Committee on the Institute of Pacific Relations.)

- Byron 1992, p. 361.

- Boughton, op. cit.

- Becker, Jasper, Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine, Macmillan (1998), ISBN 0-8050-5668-8, ISBN 978-0-8050-5668-6, pp. 290-299

- Epoch Times Staff, Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party, The Epoch Group, Broad Book USA (2005), ISBN 1-932674-16-0, ISBN 978-1-932674-16-3, p. 47

- "Mao Tse-tung's Thought Lights the Whole World" (PDF). (unstated). 28 April 1967. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- Waggoner, Walter H. (June 6, 1980). "Frank Coe, in Peking; Former U.S. Official Took Asylum in 50's". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

Frank Coe, a former Treasury Department official who was ousted as Secretary of the International Monetary Fund in the early 1950s after he was accused of being a Communist spy, died June 2 in Peking. Mr. Coe, who had lived in China since 1958, was 73 years old.

- The New York Times, op. cit., June 6, 1980, D15:4.

- J.M. Boughton, "The Case Against Harry Dexter White: Still Not Proven," IMF Working Paper 00/149

- Herbert Romerstein and Stanislav Levchenko, The KGB Against the "Main Enemy": How the Soviet Intelligence Service Operates Against the United States (Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books, 1989) ISBN 978-0-669-11228-3, pp. 106–08; John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1999) ISBN 0-300-07771-8, p. 345; Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev, The Haunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America—The Stalin Era (New York: Modern Library, 2000) ISBN 978-0-375-75536-1), pp. 48, 158, 162, 169, 229 Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev, The Haunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America - The Stalin Era (New York: Random House, 1999)

Further reading

- Haynes, John Earl; Harvey Klehr (2000). Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08462-5.

- Klehr, Harvey; John Earl Haynes; Alexander Vassiliev (2009). Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America (1st ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12390-6. (hardcover)