Messalina

Valeria Messalina (Latin: [waˈlɛria mɛssaːˈliːna]; c. 17/20–48) was the third wife of Roman emperor Claudius. She was a paternal cousin of Emperor Nero, a second cousin of Emperor Caligula, and a great-grandniece of Emperor Augustus. A powerful and influential woman with a reputation for promiscuity, she allegedly conspired against her husband and was executed on the discovery of the plot. Her notorious reputation probably resulted from political bias, but works of art and literature have perpetuated it into modern times.

| Valeria Messalina | |

|---|---|

| |

| Roman empress | |

| Tenure | 24 January 41 – 48 |

| Born | 25 January AD 17 or 20 Rome, Italy |

| Died | 48 (aged 28 or 31) Gardens of Lucullus, Rome, Italy |

| Spouse | Claudius |

| Issue | Claudia Octavia Britannicus |

| Father | Marcus Valerius Messalla Barbatus |

| Mother | Domitia Lepida |

Early life

Messalina was the daughter of Domitia Lepida and her first cousin Marcus Valerius Messalla Barbatus.[3][4] Her mother was the youngest child of the consul Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus and Antonia Major. Her mother's brother, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, had been the first husband of the future Empress Agrippina the Younger and the biological father of the future Emperor Nero, making Nero Messalina's first cousin despite a seventeen-year age difference. Messalina's grandmothers Claudia Marcella the Younger and Antonia the Elder were half sisters. Claudia Marcella Minor, Messalina's paternal grandmother, was the daughter of Augustus' sister Octavia the Younger. Antonia Major, Messalina's maternal grandmother, was the elder daughter of Octavia by her marriage to Mark Antony, and was Claudius' maternal aunt. There was, therefore, a large amount of inbreeding in the family.

Little is known about Messalina's life prior to her marriage in 38 to Claudius, her first cousin once removed, who was then about 47 years old. Two children were born as a result of their union: a daughter Claudia Octavia (born 39 or 40), a future empress, stepsister, and first wife to the emperor Nero; and a son, Britannicus. When the Emperor Caligula was murdered in 41, the Praetorian Guard proclaimed Claudius the new emperor and Messalina became empress.

Messalina's history

After her accession to power, Messalina enters history with a reputation as ruthless, predatory, and sexually insatiable, while Claudius is painted as easily led by her and unaware of her many adulteries. The historians who relayed such stories, principally Tacitus and Suetonius, wrote some 70 years after the events in an environment hostile to the imperial line to which Messalina had belonged. There was also the later Greek account of Cassius Dio who, writing a century and a half after the period described, was dependent on the received account of those before him. It has also been observed of his attitude throughout his work that he was "suspicious of women".[5] Neither can Suetonius be regarded as trustworthy. Encyclopaedia Britannica suggests of his fictive approach that he was "free with scandalous gossip," and that "he used 'characteristic anecdote' without exhaustive inquiry into its authenticity."[6] He manipulates the facts to suit his thesis.[7]

Tacitus himself claimed to be transmitting "what was heard and written by my elders" but without naming sources other than the memoirs of Agrippina the Younger, who had arranged to displace Messalina's children in the imperial succession and was therefore particularly interested in sullying her predecessor's name.[8] Examining his narrative style and comparing it to that of the satires of Juvenal, another critic remarks on "how the writers manipulate it in order to skew their audience's perception of Messalina".[9] Indeed, Tacitus seems well aware of the impression he is creating when he admits that his account may seem fictional, if not melodramatic (fabulosus).[10] It has therefore been argued that the chorus of condemnation against Messalina from these writers is largely a result of the political sanctions that followed her death,[11] although some authors have still seen "something of substance beyond mere invention".[12]

Messalina's victims

The accusations against Messalina center largely on three areas: her treatment of other members of the imperial family; her treatment of members of the senatorial order; and her unrestrained sexual behaviour. Her husband's family, especially female, seemed to be specially targeted by Messalina. Within the first year of Claudius' reign, his niece Julia Livilla, only recently recalled from banishment upon the death of her brother Caligula, was exiled again on charges of adultery with Seneca the Younger. Claudius ordered her execution soon after, while Seneca was allowed to return seven years later, following the death of Messalina.[13] Another niece, Julia Livia, was attacked for immorality and incest by Messalina in 43 – possibly because she feared Julia's son Rubellius Plautus as a rival claimant to the imperial succession,[13] – with the result that Claudius ordered her execution.[14]

In the final two years of her life, she also intensified her attacks on her husband's only surviving niece, Agrippina the Younger, and Agrippina's young son Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (the later Emperor Nero). The public sympathized with Agrippina, who had twice been exiled and was the only surviving daughter of Germanicus after Messalina secured the execution of Julia Livilla. Agrippina was implicated in the alleged crimes of Statilius Taurus, whom it was alleged she directed to partake in "magical and superstitious practices".[15] Taurus committed suicide, and, according to Tacitus, Messalina was only prevented from further persecuting Agrippina because she was distracted by her new lover, Gaius Silius.[16]

According to Suetonius, Messalina realized early on that the young Nero could be a potential rival to her own son, who was three years younger. He repeated a tale that Messalina sent several assassins into Nero's bedchamber to murder him, but they were frightened off by what they thought was a snake slithering out from under his bed.[17] In the Secular Games of 48, Nero won greater applause from the crowd than did Messalina's own son Britannicus, something which scholars have speculated led Messalina to plot to destroy Nero and his mother once and for all.[18]

Two very prominent senators, Appius Silanus and Valerius Asiaticus, also met their death on the instigation of Messalina. The former was married to Messalina's mother Domitia Lepida, but according to Dio and Tacitus, Messalina coveted him for herself. In 42, Messalina and the freedman Narcissus devised an elaborate ruse, whereby they each informed Claudius that they had had identical dreams during the night portending that Silanus would murder Claudius. When Silanus arrived that morning (after being summoned by either Messalina or Narcissus), he confirmed their portent and Claudius had him executed.[19][20][21]

Valerius Asiaticus was one of Messalina's final victims. Asiaticus was immensely rich and incurred Messalina's wrath because he owned the Gardens of Lucullus, which she desired for herself, and because he was the lover of her hated rival Poppaea Sabina the Elder, with whom she was engaged in a fierce rivalry over the affections of the actor Mnester.[22] In 46, she convinced Claudius to order his arrest on charges of failing to maintain discipline amongst his soldiers, adultery with Sabina, and for engaging in homosexual acts.[23][24] Although Claudius hesitated to condemn him to death, he ultimately did so on the recommendation of Messalina's ally, and Claudius' partner in the consulship for that year, Lucius Vitellius.[25] The murder of Asiaticus, without notifying the senate and without trial, caused great outrage amongst the senators, who blamed both Messalina and Claudius.[26] Despite this, Messalina continued to target Poppaea Sabina until she committed suicide.[27]

The same year as the execution of Asiaticus, Messalina ordered the poisoning of Marcus Vinicius – because he refused to sleep with her according to gossip.[28] About this time she also arranged for the execution of one of Claudius' freedmen secretaries, Polybius. According to Dio, this murder of one of their own turned the other freedmen, previously her close allies, against Messalina for good.

Downfall

In 48 AD, Claudius went to Ostia to visit the new harbor he was constructing and was informed while there that Messalina had gone so far as to marry her latest lover, Senator Gaius Silius in Rome. It was only when Messalina held a costly wedding banquet in Claudius' absence that the freedman Narcissus decided to inform him.[29] The exact motivations for Messalina's actions are unknown – it has been interpreted as a move to overthrow Claudius and install Silius as Emperor, with Silius adopting Britannicus and thereby ensuring her son's future accession.[30] Other historians have speculated that Silius convinced Messalina that Claudius' overthrow was inevitable, and her best hopes of survival lay in a union with him.[31][32] Tacitus stated that Messalina hesitated even as Silius insisted on marriage, but ultimately conceded because "she coveted the name of wife", and because Silius had divorced his own wife the previous year in anticipation of a union with Messalina.[33] Another theory is that Messalina and Silius merely took part in a sham marriage as part of a Bacchic ritual as they were in the midst of celebrating the Vinalia, a festival of the grape harvest.[34]

Tacitus and Dio state that Narcissus convinced Claudius that it was a move to overthrow him[29] and persuaded him to appoint the deputy Praetorian Prefect, Lusius Geta, to the charge of the Guard because the loyalty of the senior Prefect Rufrius Crispinus was in doubt.[18][35][29] Claudius rushed back to Rome, where he was met by Messalina on the road with their children. The leading Vestal Virgin, Vibidia, came to entreat Claudius not to rush to condemn Messalina. He then visited the house of Silius, where he found a great many heirlooms of his Claudii and Drusii forebears, taken from his house and gifted to Silius by Messalina.[36] When Messalina attempted to gain access to her husband in the palace, she was repulsed by Narcissus and shouted down with a list of her various offences compiled by the freedman. Despite the mounting evidence against her, Claudius's feelings were softening and he asked to see her in the morning for a private interview.[37] Narcissus, pretending to act on Claudius' instructions, ordered an officer of the Praetorian Guard to execute her. When the troop of guards arrived at the Gardens of Lucullus, where Messalina had taken refuge with her mother, she was given the honorable option of taking her own life. Unable to muster the courage to slit her own throat, she was run through with a sword by one of the guards.[38][37] Upon hearing the news, the Emperor did not react and simply asked for another chalice of wine. The Roman Senate then ordered a damnatio memoriae so that Messalina's name would be removed from all public and private places and all statues of her would be taken down.

Erasure from memory

In Messalina's time, the condemnation of damnatio memoriae followed on an offence within the context of the Roman imperial cult. The cult was directed from above by members of the imperial circle through official initiatives within the pro-imperial power structure. It was effective among the wider public, however, only insofar as there was personal assent. Theoretically the sentence of damnatio memoriae was supposed to erase all mention of the offender from the public sphere. The person's name was gouged from inscriptions and even from coinage. Sculptures might be smashed or at the very least would be dismounted and stored away out of sight.

Such measures were not totally effective and several images of Messalina have survived for one reason or another.[39] One such is the doubtfully ascribed bust in the Uffizi Gallery that may in fact be of Agrippina, Messalina's successor as wife of Claudius (see above). Another in the Louvre is thought to be of Messalina holding her child Britannicus. In fact it is based on a famous Greek sculpture by Cephisodotus the Elder of Eirene carrying the child Ploutos, of which there were other Roman imitations.[40]

Some of the surviving engraved gems that feature Messalina were also indebted to ancient Greek models. They include the carved sardonyx of Messalina accompanied by Claudius in a dragon chariot, which commemorated his part in the Roman conquest of Britain. This was modelled on depictions of Dionysus and Ariadne after his Indian victory and is now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Cabinet des Médailles).[41] In its Roman adaptation, Messalina is in front guiding the chariot while Claudius stands behind her steadying his flying robe. The piece was once in the collection of Peter Paul Rubens, who made an ink sketch of it, although identifying the woman erroneously as Agrippina.[42] However, there is another version of this victory celebration known as the Hague cameo, which may be a later imitation. In a chariot drawn by centaurs, the laurel-wreathed Messalina reclines in the post of honour, bearing the attributes of Ceres. Beside her sits Claudius with one arm about her neck and Jupiter's thunderbolt in his other hand. In front stands the child Britannicus in complete armour, with his elder sister Octavia next to him.[43][44]

Yet another carved sardonyx now in the national library of France represents a bust of the laureled Messalina, with on either side of her the heads of her son and daughter emerging from a cornucopia.[45] This too once belonged to Rubens and a Flemish engraving after his drawing of it is in the British Museum.[46] A simple white portrait bust of the empress is also held by the Bibliothèque nationale.[47] A portrait oval in yellow carnelian was once recorded as being in the collection of Lord Montague;[48] another in sardonyx once belonged to the Antikensammlung Berlin.[49]

Two authors especially supplemented the gossip and officially dictated versions recorded by later historians and added to Messalina's notoriety. One such story is the account of her all-night sex competition with a prostitute in Book X of Pliny the Elder's Natural History, according to which the competition lasted "night and day" and Messalina won with a score of 25 partners.[50]

The poet Juvenal mentions Messalina twice in his satires. As well as the story in his tenth satire that she compelled Gaius Silius to divorce his wife and marry her,[51] the sixth satire contains the notorious description of how the Empress used to work clandestinely all night in a brothel under the name of the She-Wolf.[52] In the course of that account, Juvenal coined the phrase frequently applied to Messalina thereafter, meretrix augusta (the imperial whore). In so doing, he coupled her reputation with that of Cleopatra, another victim of imperially directed character assassination, whom the poet Propertius had earlier described as meretrix regina (the harlot queen).[53]

The earlier propaganda against Cleopatra is described as "rooted in the hostile Roman literary tradition".[54] Similar literary tactics, including the suggestive mingling of historical fact and gossip in the officially approved annals, is what has helped prolong the scandalous reputation of Messalina as well.

Messalina in the arts

To call a woman "a Messalina" indicates a devious and sexually voracious personality. The historical figure and her fate were often used in the arts to make a moral point, but there was often as well a prurient fascination with her sexually-liberated behaviour.[55] In modern times, that has led to exaggerated works which have been described as romps.[56]

_-_Gothenburg_Museum_of_Art_-_GKM_0173.tif.jpg.webp)

The ambivalent attitude to Messalina can be seen in the late mediaeval French prose work in the J. Paul Getty Museum illustrated by the Master of Boucicaut, Tiberius, Messalina, and Caligula reproach one another in the midst of flames. It recounts a dialogue that takes place in hell between the three characters from the same imperial line. Messalina wins the debate by demonstrating that their sins were far worse than hers and suggests that they repent of their own wickedness before reproaching her as they had done.[57]

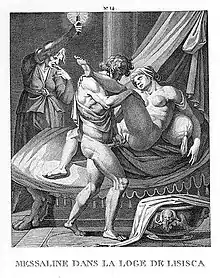

While Messalina's wicked behavior towards others is given full emphasis, and even exaggerated in early works, her sexual activities have been treated more sympathetically. In the 1524 illustrations of 16 sexual positions known as I Modi, each was named after a couple from Classical history or myth, which included "Messalina in the Booth of Lisisca". Although early editions were destroyed by religious censorship, Agostino Caracci's later copies have survived (see above).

Other artistic illustrations of Messalina's reported depravity, supposedly based on ancient medals and cameos, appear in the works of Pierre-François Hugues d'Hancarville. His main account, padded with more general quotations condemning the laxity of the times, takes up three chapters of his Monuments of the Private Lives of the Twelve Caesars (1780).[58] Chapter 29 deals with Messalina's public marriage to Gaius Silius. The following chapters are illustrated by cameos ascribed to a certain Pythodorus of Trallès. In the first, Messalina sits naked while a maid dresses her hair in preparation for taking up her role as the courtesan Lisisica; in the other she offers fourteen myrtle wreaths to Priapus following her triumph in exhausting as many fit young men in a sexual contest. She also sits before a private shrine to Priapus in an illustration for the author's other pornographic work, Monuments of the Secret Cult of Roman Women (1787).[59]

Later painting and sculpture

One of the avenues to drawing a moral lesson from the story of Messalina in painting was to picture her violent end. An early example was Francesco Solimena's The Death of Messalina (1708).[60] In this scene of vigorous action, a Roman soldier pulls back his arm to stab the Empress while fending off her mother. A witness in armour observes calmly from the shadows in the background. Georges Rochegrosse's painting of 1916 is a reprise of the same scene.[61] A mourning woman dressed in black leaves with her face covered as a soldier drags back Messalina's head, watched by a courtier with the order for execution in his hand. The Danish royal painter Nicolai Abildgaard, however, preferred to feature "The Dying Messalina and her Mother" (1797) in a quieter setting. The mother weeps beside her daughter as she lies extended on the ground in a garden setting.[62]

In 1870 the French committee for the Prix de Rome set Messalina's death as the competition subject for that year. The winning entry by Fernand Lematte, The Death of Messalina, is based on the description of the occasion by Tacitus. Following the decision that she must die, "Evodus, one of the freedmen, was appointed to watch and complete the affair. Hurrying on before with all speed to the gardens, he found Messalina stretched upon the ground, while by her side sat Lepida, her mother, who, though estranged from her daughter in prosperity, was now melted to pity by her inevitable doom, and urged her not to wait for the executioner".[63] In Messalina's hand is the thin dagger that she dare not use, while Evodus bends over her threateningly and Lepida tries to fend him off. In an earlier French treatment by Victor Biennoury, the lesson of poetic justice is made plainer by specifically identifying the scene of Messalina's death as the garden which she had obtained by having its former owner executed on a false charge. Now she crouches at the foot of a wall carved with the name of Lucullus and is condemned by the dark-clothed intermediary as a soldier advances on her drawing his sword.[64]

Two Low Countries painters emphasised the behaviour of Messalina that led up to her end by picturing her wedding with Gaius Silius. The one by Nicolaus Knüpfer, dated about 1650, is so like contemporary brothel scenes that its subject is ambiguous and has been disputed. A richly dressed drunkard lies back on a bed between two women while companions look anxiously out of the window and another struggles to draw his sword.[65] The later "Landscape with Messalina's Wedding" by Victor Honoré Janssens pictures the seated empress being attired before the ceremony.[66] Neither scene looks much like a wedding, but rather they indicate the age's sense of moral outrage at this travesty of marriage. That was further underlined by a contemporary Tarot card in which card 6, normally titled "The Lover(s)", has been retitled "Shameless" (impudique) and pictures Messalina leaning against a carved chest. Beneath is the explanation that "she reached such a point of insolence that, because of the stupidity of her husband, she dared to marry a young Roman publicly in the Emperor's absence".[67]

The wild scenes following the wedding that took place in Rome are dramatised by Tacitus. "Messalina meanwhile, more wildly profligate than ever, was celebrating in mid-autumn a representation of the vintage in her new home. The presses were being trodden; the vats were overflowing; women girt with skins were dancing, as Bacchanals dance in their worship or their frenzy. Messalina with flowing hair shook the thyrsus, and Silius at her side, crowned with ivy and wearing the buskin, moved his head to some lascivious chorus".[68] Such was the scene of drunken nudity painted by fr:Gustave Surand in 1905.[69]

Other artists show similar scenes of debauchery or, like the Italian A. Pigma in When Claudius is away, Messalina will play (1911),[70] hint that it will soon follow. What was to follow is depicted in Federico Faruffini's The orgies of Messalina (1867–1868).[71] A more private liaison is treated in Joaquín Sorolla's Messalina in the Arms of the Gladiator (1886).[72] This takes place in an interior, with the empress reclining bare breasted against the knees of a naked gladiator.

Juvenal's account of her nights spent in the brothel is commonly portrayed. Gustave Moreau painted her leading another man onto the bed while an exhausted prostitute sleeps in the background,[73] while in Paul Rouffio's painting of 1875 she reclines bare-breasted as a slave offers grapes.[74] The Dane Peder Severin Krøyer depicted her standing, her full body apparent under the thin material of her dress. The ranks of her customers are just visible behind the curtain against which she stands (see above). Two drawings by Aubrey Beardsley were produced for a private printing of Juvenal's satires (1897). The one titled Messalina and her companion showed her on the way to the brothel,[75] while a rejected drawing is usually titled Messalina returning from the bath.[76] About that period, too, Roman resident Pavel Svedomsky reimagined the historical scene. There the disguised seductress is at work in a light-suffused alley, enticing a passer-by into the brothel from which a maid looks out anxiously.[77]

Alternatively, artists drew on Pliny's account of her sex competition. The Brazilian Henrique Bernardelli (1857–1936) showed her lying across the bed at the moment of exhaustion afterwards.[78] So also did Eugène Cyrille Brunet's dramatic marble sculpture, dating from 1884 (see above), while in the Czech Jan Štursa's standing statue of 1912 she is holding a last piece of clothing by her side at the outset.[79]

Drama and spectacle

One of the earliest stage productions to feature the fall of the empress was The Tragedy of Messalina (1639) by Nathanael Richards,[80] where she is depicted as a monster and used as a foil to attack the Roman Catholic wife of the English king Charles I.[81] She is treated as equally villainous in the Venetian Pietro Zaguri's La Messalina (1656). This was a 4-act prose tragedy with four songs, described as an opera scenica, that revolved around the affair with Gaius Silius that brought about her death.[82] Carlo Pallavicino was to follow with a full blown Venetian opera in 1679 that combined eroticism with morality.[83][84]

During the last quarter of the 19th century the idea of the femme fatale came into prominence and encouraged many more works featuring Messalina. 1874 saw the Austrian verse tragedy Arria und Messalina by Adolf Wilbrandt[85] which was staged with success across Europe for many years. It was followed in 1877 by Pietro Cossa's Italian verse tragedy, where Messalina figures as a totally unrestrained woman in pursuit of love.[86] Another 5-act verse tragedy was published in Philadelphia in 1890,[87] authored by Algernon Sydney Logan (1849–1925), who had liberal views on sex.[88]

As well as plays, the story of Messalina was adapted to ballet and opera. The 1878 ballet by Luigi Danesi (1832-1908) to music by Giuseppe Giaquinto (d. 1881) was an Italian success with several productions.[89] On its arrival in France in 1884 it was made a fantastical spectacle at the Éden-Théâtre, with elephants, horses, massive crowd scenes and circus games in which rows of bare-legged female gladiators preceded the fighters.[90][91] Isidore de Lara's opera Messaline, based on a 4-act verse tragedy by Armand Silvestre and Eugène Morand, centred upon the love of the empress for a poet and then his gladiator brother. It opened in Monte Carlo in 1899 and went on to Covent Garden.[92] The ailing Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec saw the Bordeaux production and was inspired to paint six scenes from it, including Messalina descending a staircase, seated while a bearded character in a dark tunic stands to one side, or the same character stands[93] and kneels before her,[94] as well as resting extras.[95] Later there was also an Italian production of the opera in translation.[96]

In 2009 the theme was updated by Benjamin Askew in his UK play In Bed With Messalina, which features her final hours.[97]

Stars of stage and screen

From the last quarter of the 19th century onwards, the role of Messalina has been as much about the stardom of those who played her as about the social message of the works in which she appeared.[98] The star's name appeared in large print on the posters of the works in which she played. She was constantly featured in the gossip columns. Her role was iconised photographically, copies of which she often inscribed for her admirers.[99] Pictures of her as Messalina adorned the theatre magazines and were sold in their thousands as postcards. This was as true in drama and opera as it was of those who portrayed the empress in movies and television films or miniseries. The role itself added to or established their reputations. And, with the growing permissiveness of modern times, that might rather amount to notoriety for those adult films in which athletic stamina was more of a requirement than acting ability.

Wilbrandt's Arria und Messalina was specially written for Charlotte Wolter, who was painted in her role by Hans Makart in 1875. There she reclines on a chaise-longue as the lights of Rome burn in the background. As well as a preparatory photograph of her dressed as in the painting,[100] there were also posed cabinet photos of her in a plainer dress.[101] Other stars were involved when the play went on tour in various translations. Lilla Bulyovszkyné (1833–1909) starred in the Hungarian production in 1878[102] and Irma Temesváryné-Farkas in that of 1883;[103] Louise Fahlman (1856–1918) played in the 1887 Stockholm production,[104] Marie Pospíšilová (1862–1943) in the 1895 Czech production.[105]

In Italy, Cossa's drama was acted with Virginia Marini in the role of Messalina.[106]

Both the Parisian leads in Danesi's ballet were photographed by Nadar: Elena Cornalba in 1885[107] and Mlle Jaeger later.[108] During its 1898 production in Turin, Anita Grassi was the lead.[109]

Meyriane Héglon starred in the Monte Carlo and subsequent London productions of De Lara's Messaline,[110] while Emma Calvé starred in the 1902 Paris production,[111][112] where she was succeeded by Cécile Thévenet.[113] Others who sang in the role were Maria Nencioni in 1903,[114] Jeanne Dhasty in the Nancy (1903) and Algiers (1907) productions,[115] Charlotte Wyns (1868–c. 1917) in the 1904 Aix les Bains production,[116] and Claire Croiza, who made her debut in the 1905 productions in Nancy and Lille.[117]

Films

After a slow start in the first half of the 20th century, the momentum of films about or featuring Messalina increased with censorship's decline. The following starred in her part:

- Madeleine Roch (1883–1930) in the French silent film Messaline (1910).[118][119]

- Maria Caserini in the 1910 Italian silent film The Love of an Empress (Messalina).[120]

- Rina De Liguoro in the 1923 Italian silent film Messalina, a sword-and-sandal precursor alternatively titled The Fall of an Empress.[121][122] A cut version with dubbed dialogue was released in 1935.

- Merle Oberon in the 1937 uncompleted film of I, Claudius.[123]

- María Félix in the 1951 Italian sword-and-sandal film Messalina. This also carried the titles Empress of Rome[124] and The Affairs of Messalina.[125]

- Ludmilla Dudarova during a flashback in Nerone e Messalina (Italy, 1953), which had the English title Nero and the Burning of Rome.[126]

- Susan Hayward in the 1954 Biblical epic Demetrius and the Gladiators,[127] a completely fictionalized interpretation in which a reformed Messalina bids a penitential public farewell to her Christian gladiator lover, Demetrius, and takes her place on the throne next to her husband, the new emperor Claudius.[128]

- Belinda Lee in the 1960 sword-and-sandal film Messalina, venere imperatrice.[129]

- Lisa Gastoni in The Final Gladiator (L'ultimo gladiatore), or alternatively The Gladiator of Messalina,[130] an Italian sword-and-sandal film also titled Messalina vs. the Son of Hercules (1963).[131]

- Nicola Pagett in the 1968 ITV television series The Caesars.[132] The series is noted for its historically accurate depiction of Roman history and personages, including a less sensationalised portrayal of Messalina.

- Sheila White in the 1976 BBC serial I, Claudius.[133]

- Anneka Di Lorenzo in the 1979 film Caligula, and the 1977 comedy Messalina, Messalina, which used many of the same set pieces as the earlier-filmed, but later-released Caligula.[134] An alternative European title for the 1977 production was Messalina, Empress and Whore.[135][136]

- Betty Roland in the Franco-Italian "porno peplum" Caligula and Messalina (1981).[137]

- Raquel Evans in the 1982 Spanish comedy Bacanales Romanas, released in English as the "porno peplum" My Nights with Messalina.[138]

- Jennifer O'Neill in the 1985 TV series AD.[139]

- Sonia Aquino in the 2004 TV movie Imperium: Nero.[140]

- Tabea Tarbiat in the 2013 film Nymphomaniac Volume II.[141]

Fiction

An early fiction concerning the Empress, La Messalina by Francesco Pona, appeared in Venice in 1633. This managed to combine a high degree of eroticism with a demonstration of how private behavior has a profound effect on public affairs. Nevertheless, a passage such as

- Messalina tossing in the turbulence of her thoughts did not sleep at night; and if she did sleep, Morpheus slept at her side, prompting stirrings in her, robing and disrobing a thousand images that her sexual fantasies during the day had suggested

helps explain how the novel was at once among the most popular, and the most frequently banned, books of the century, despite its moral pretensions.[142]

Much the same point about the catastrophic effect of sexuality was made by Gregorio Leti's political pamphlet, The amours of Messalina, late queen of Albion, in which are briefly couch'd secrets of the imposture of the Cambrion prince, the Gothick league, and other court intrigues of the four last years reign, not yet made publick (1689).[143] This was yet another satire on a Stuart Queen, Mary of Modena in this case, camouflaged behind the character of Messalina.

A very early treatment in English of Messalina's liaison with Gaius Silius and her subsequent death appeared in the fictionalised story included in the American author Edward Maturin's Sejanus And Other Roman Tales (1839).[144] But the part she plays in Robert Graves' novels, I, Claudius and Claudius the God (1934–35), is better known. In it she is portrayed as a teenager at the time of her marriage but credited with all the actions mentioned in the ancient sources. An attempt to create a film based on them in 1937 failed,[145] but they were adapted into a very successful TV series in 1976.

In 19th century France, the story of Messalina was subject to literary transformation. It underlaid La femme de Claude (Claudius' wife, 1873), the novel by Alexandre Dumas fils, where the hero is Claude Ruper, an embodiment of the French patriotic conscience after the country's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. In contrast, his wife Césarine (the female Caesar) is a creature totally corrupt at all levels, who sells her husband's work to the enemy and is eventually shot by him.[146] Alfred Jarry's 'pataphysical' novel Messaline of 1901 (titled The Garden of Priapus in Louis Colman's English translation), though lightly based on the historical account, is chiefly the product of the author's fanciful and extravagant imagination and has been compared with the treatment of Classical themes by Art Nouveau artists.[147]

In fact, Jarry's was just one of five contemporary French novels treating Messalina in a typically fin de siècle manner. They also included Prosper Castanier's L'Orgie Romaine (Roman Orgy, 1897), Nonce Casanova's Messaline, roman de la Rome impériale (Mesalina, a novel of imperial Rome, 1902) and Louis Dumont's La Chimère, Pages de la Décadence (The Chimaera, Decadent Pages, 1902). However, the most successful and inventive stylistically was Felicien Champsaur's novel L'Orgie Latine (1903)[148] Although Messalina is referenced throughout its episodic coverage of degenerate times, she features particularly in the third section, "The Naked Empress" (L'impératice nue), dealing with her activities in the brothel, and the sixth, "Messalina's End", beginning with her wedding to Silius and ending with her enforced death.[149]

Sensational fictional treatments have persisted, as in Vivian Crockett's Messalina, the wickedest woman in Rome (1924), Alfred Schirokauer's Messalina – Die Frau des Kaisers (Caesar's wife, 1928),[150] Marise Querlin's Messaline, impératrice du feu (The fiery empress, 1955), Jack Oleck's Messalina: a novel of imperial Rome (1959) and Siegfried Obermeier's Messalina, die lasterhafte Kaiserin (The empress without principle, 2002). Oleck's novel went through many editions and was later joined by Kevin Matthews' The Pagan Empress (1964). Both have since been included under the genre "toga porn".[151] They are rivalled by Italian and French adult comics, sometimes of epic proportions, such as the 59 episodes devoted to Messalina in the Italian Venus of Rome series (1967–74).[152] More recent examples include Jean-Yves Mitton's four-part series in France (2011–13)[153] and Thomas Mosdi's Messaline in the Succubus series (#4, 2014), in which "a woman without taboos or scruples throws light on pitiless ancient Rome".[154]

Contrasting views have lately been provided by two French biographies. Jacqueline Dauxois gives the traditional picture in her lurid biography in Pygmalion's Legendary Queens series (2013),[155] while the historian Jean-Noël Castorio (b.1971) seeks to uncover the true facts of the woman behind Juvenal's 6th satire in his revisionist Messaline, la putain impériale (The imperial whore, 2015).[156]

Notes

- Susan Wood, "Messalina, wife of Claudius: propaganda successes and failures of his reign", Journal of Roman Archaeology, Volume 5, 1992, p. 334, suggests that the group was preserved from the destruction following her damnatio memoriae by a supporter who kept it in his home.

- Eric R. Varner, Mutilation and Transformation, Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture, Leiden, Brill, 2004., p. 96, writes that the group was warehoused after her damnatio memoria.

- Prosopographia Imperii Romani V 88

- Suetonius, Vita Claudii, 26.29

- Adam Kemezis, The Bryn Mawr Classical Review, 7 March, 2005

- "Suetonius | Roman author". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, "Suetonius as Historian", The Classical Review New Series, Vol. 36.2 (1986), pp. 243–245

- K.A.Hosack, "Can One Believe the Ancient Sources That Describe Messalina?", Constructing the Past 12.1, 2011]

- Nicholas Reymond, Meretrix Augusta: The Treatment of Messalina in Tacitus and Juvenal, McMaster University 2000

- Katharine T. von Stackelberg, "Performative Space and Garden Transgressions in Tacitus' Death of Messalina", The American Journal of Philology 130.4 (Winter, 2009), pp. 595–624

- Harriet I. Flower, The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace and Oblivion in Roman Political Culture, University of North Carolina 2011, pp. 182–189

- Thomas A. J. McGinn, Prostitution, Sexuality, and the Law in Ancient Rome, Oxford University 1998 p. 170

- Barbara Levick (1990). Claudius. Yale University Press. p. 56.

- Anthony Barrett (1996). Agrippina: Sex, Power and Politics in the Early Roman Empire. Yale University Press. pp. 87, 104.

- Tacitus, Annals XII.59.1

- Tacitus, Annales, XI.10

- Suetonius. Lives of the Caesars: Claudius I.VI.

- Barbara Levick (1990). Claudius. Yale University Press. p. 65.

- Tacitus, Annales, iv. 68, vi. 9, xi. 29.

- Suetonius, "The Life of Claudius", 29, 37.

- Cassius Dio, ix. 14.

- Tacitus, Annals, 11.2

- Barbara Levick (1990). Claudius. Yale University Press. p. 62.

- Alston, Aspects of Roman History AD 14–117, p. 95

- Barbara Levick (1990). Claudius. Yale University Press. pp. 61–62.

- Barbara Levick (1990). Claudius. Yale University Press. p. 64.

- Tacitus, Annales, XI.1–3

- Cassius Dio 60, 27, 4

- Cassius Dio, Roman History. Book LXI.31

- Barbara Levick (1990). Claudius. Yale University Press. pp. 64–67.

- Arnoldo Momigliano (1934). Claudius: The Emperor and His Achievement. W. Heffer & Sons. pp. 6–7.

- Vincent Scramuzza (1940). The Emperor Claudius. Harvard University Press. p. 90.

- Tacitus. Annals. p. Book XI.XXVI.

- Barbara Levick (1990). Claudius. Yale University Press. p. 67.

- Tacitus. Annals. p. Book XI.XXVII.

- Tacitus. Annals. p. Book XI.XXXV.

- Tacitus. Annals. p. Book XI.XXXVI.

- Tom Holland (2015). Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar. p. 334.

- Eric R. Varner, "Portraits, Plots, and Politics: "Damnatio memoriae" and the Images of Imperial Women", Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 46 (2001), pp. 41-93

- Wikimedia

- Gallery of Ancient Art

- Photo on Flickr

- C.W.King, Handbook of Engraved Gems (London 1885), p.57

- The Hague cameo

- The Paris cameo

- BM Museum number 1891,0414.1238

- Cameo Jewels of Ancient Rome

- Copperplate engraving by Thomas Worlidge from James Vallentin's One Hundred and Eight Engravings from Antique Gems, 1863, #65

- Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

- Online translation, X ch.83

- Satire X, translated by A. S. Kline, lines 329–336

- "Juvenal (55–140) – The Satires: Satire VI". poetryintranslation.com.

- Gilmore, John T. (2017). Satire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134106332 – via Google Books.

- Margaret M. Miles, "Cleopatra in Egypt, Europe and New York" in Cleopatra: A Sphinx Revisited, University of California 2011, p. 17

- Peter Maxwell Cryle, The Telling of the Act: Sexuality As Narrative in Eighteenth- And Nineteenth-Century France, University of Delaware 2001. Messalina chapter, pp. 281ff

- 'Jack Oleck's Messalina is a full-on romp in the salacious world of Imperial Rome’; My nights with Messalina is a stupid little romp, and quite good at it too'

- "Wiki-Commons".

- Monumens de la Vie Privée des Douze Césars, Chez Sabellus, Capri chapters 29-31

- Monumens du Culte Secret des Dames Romaines, Sabellus, Capri (Leclerc, Nancy) Illustration 32

- "Death of Messalina (Getty Museum)". The J. Paul Getty in Los Angeles.

- "The Death of Messalina :: Georges Antoine Rochegrosse – Antique world scenes". fineartlib.info.

- Wiki-Media

- Annales 11.37

- Wiki-Commons

- Wiki-Commons

- Wiki-Commons

- "Valeria Messalina; Messalline; Kaartspel met gerenommeerde heerseressen; Jeu des reynes renommées". Europeana Collections.

- Annales 11.31

- Wikimedia

- Limited, Alamy. "Stock Photo – When Claudius Is Away, Messalina Will Play by A.Pigma (1911)". Alamy.

- Wiki-Commons

- Wiki-Media

- "Messalina : Gustave Moreau : Museum Art Images : Museuma". 4 March 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- "Art Value".

- "'Messalina and her Companion', Aubrey Beardsley, 1895". Tate.

- Victoria & Albert Museum

- Messalina at AKG Images

- Wiki-Commons

- Štursa, Jan. "Français : Messaline" – via Wikimedia Commons.

- Online text

- Lisa Hopkins, The Cultural Uses of the Caesars on the English Renaissance Stage, 2008 pp. 135–137

- Text at Internet Archive

- Wendy Heller, Emblems of Eloquence: Opera and Women's Voices in Seventeenth-Century Venice, University of California 2003, pp. 277–297

- Text at Internet Archive

- Wilbrandt, Adolf "von" (21 October 1874). "Arria und Messalina: Trauerspiel in 5 Aufz". Rosner – via Google Books.

- Cossa, Pietro (21 October 1877). "Messalina: commedia in 5 atti in versi, con prologo". F. Casanova – via Google Books.

- "Messalina: A Tragedy in Five Acts". J.B. Lippincott company. 21 October 1890 – via Internet Archive.

- "Collecting Delaware Books – Vistas from a Kent County Stream". jnjreid.com.

- A programme and resume of the 1898 Turin production at Internet Archive

- Sarah Gutsche-Miller, Pantomime-Ballet on the Music-Hall Stage, McGill University thesis, 2010,p. 36

- "Magazine illustration".

- "Messaline, "Maitres de l'Affiche" plate 187 | Limited Runs". www.limitedruns.com.

- [https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:Search&limit=100&offset=0&profile=default&search=File%3AMessalina&ns0=1#/media/File:Toulouse-Lautrec_-_Messalina,_1900.jpg Wiki-Media

- Media storehouse

- Media storehouse

- Published in Piacenza, 1904

- "Theatre review: In Bed With Messalina at Courtyard Theatre, Hoxton". British Theatre Guide.

- Wyke, Maria (2007). The Roman Mistress: Ancient and Modern Representations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199228331 – via Google Books.

- Thomas F. Connolly, Genus Envy: Nationalities, Identities, and the Performing Body of Work, Cambria Press 2010, pp. 102–103

- Limited, Alamy. "Stock Photo – Charlotte Wolter, Austrian actress, in costume as Messalina, lounging on a Chaise longue". Alamy.

- "Austrian picture archive".

- "Arria és Messalina szomorujáték 5 felvonásban – irta Willbrant – forditotta Dr Váradi Antal". Europeana Collections.

- "Arria és Messalina szomorujáték 5 felvonásban – irta: Willbrand – forditotta: dr. Várady Antal". Europeana Collections.

- photographic portraits on Wiki-Commons and Alamy

- "Pospíšilová, Marie". Europeana Collections.

- "Messalina – Archivio digitale della Fondazione Giorgio Cini Onlus". archivi.cini.it.

- Photographe, Atelier Nadar (21 October 1885). "Cornalba. Eden. [Messalina] : [photographie, tirage de démonstration] / [Atelier Nadar]". Gallica.

- Photographe, Atelier Nadar (21 October 1885). "Jager [i.e. Jaeger]. Eden. Messalina : [photographie, tirage de démonstration] / [Atelier Nadar]". Gallica.

- Giaquinto, Giuseppe; Danesi, Luigi (21 October 1898). "Messlina : azione storica coreografica in 8 quadri". Torino: Tip. M. Artale – via Internet Archive.

- "Meyriane Heglon". ipernity.

- Archived score.

- "Missing Account | Piwigo". piwigo.com.

- Reutlinger, Jean (21 October 1903). "[Album Reutlinger de portraits divers, vol. 29] : [photographie positive] : Thévenet dans Messaline;" – via Wikimedia Commons.

- Postcard,

- "Postcard".

- "Wyns Charlotte".

- Photograph on Wiki-Commons

- Frédéric Zarch, Catalogue des films projetés à Saint-Étienne avant la première guerre mondiale, Université de Saint-Etienne, 2000, p.209

- Poster

- "Messalina (1910)". IMDb.

- "Messalina – a photo on Flickriver". flickriver.com.

- Poster and still at Film Addinity

- "Merle Oberon as Messalina in the London Film production, I Claudius". 16 January 2011 – via Flickr.

- "Messalina Empress of Rome". filmplakater. 15 May 2012.

- "Poster".

- "Archivo Storico del Cinema".

- "Poster with Hayward in the foreground".

- Martin M. Winkler, Cinema and Classical Texts: Apollo's New Light, Cambridge University 2009, p. 232

- "The German poster".

- Screen shot and poster at World Cult Cinema

- "L'ultimo gladiatore / Messalina vs. the Son of Hercules (1964) Umberto Lenzi, Richard Harrison, Marilù Tolo, Philippe Hersent, Adventure, Drama | RareFilm". rarefilm.net.

- "Upstairs, Downstairs – Out of costume – Before UpDown 2". updown.org.uk.

- "Messalina – I, Claudius (UK) Characters". sharetv.com.

- "Messalina, Messalina". IMDb.

- Gary Allen Smith, Epic Films: Casts, Credits and Commentary, McFardland 2004, p. 168

- Poster

- "Poster on Pinterest".

- Suni, Jetro. "fixgalleria.net". fixgalleria.net.

- "Jennifer O'Neill as Messalina Pretty Portrait A.D. original 1985 NBC TV Photo". eBay.

- "Publicity photo".

- "Nymphomaniac Volume II – Full cast credits". IMDb.

- Wendy Heller, Emblems of Eloquence: Opera and Women's Voices in Seventeenth-Century Venice, University of California 2003, pp. 273–275

- Leti, Gregorio (21 October 1689). "The Amours of Messalina, Late Queen of Albion: In which are Briefly Couch'd, Secrets of the Imposture of the Cambrion Prince, The Gothick League And Other Court Intrigues of the Four Last Rears Reign, Not Yet Made Publick". Lyford – via Google Books.

- Maturin, Edward (21 October 1839). "Sejanus: And Other Roman Tales". F. Saunders – via Google Books.

- William Hawes, Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom, Jefferson NC 2009, pp. 14–16

- "La femme de Claude, Alexandre Dumas fils". epelorient.free.fr.

- The Nineteenth Century in Two Parts, Syracuse University 1994 p. 1214

- Archived online; there has also been a recent translation as The Latin Orgy.

- Marie-France David-de Palacio, Reviviscences romaines: la latinité au miroir de l'esprit fin-de-siècle, Peter Lang, 2005, p. 232

- "Kapitel 2 des Buches: Messalina von Alfred Schirokauer | Projekt Gutenberg". gutenberg.spiegel.de. Hamburg, Germany: Spiegel Online.

- Joanne Renaud, in Astonishing Adventures Magazine 5, 2009, pp. 52–55

- "Messalina (Volume)". Comic Vine.

- "Comib Strips Cafe, librairie du portail CANAL BD". www.canalbd.net.

- "Succubes, tome 4 : Messaline – Thomas Mosdi". Babelio.

- "Messaline". Arrête ton char.

- "Messaline, la putain impériale (J.-N. Castorio)". histoire-pour-tous.fr.

References

- Holland, Tom (1990). Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar. Doubleday.

- (in French) Minaud, Gérard, Les vies de 12 femmes d'empereur romain – Devoirs, Intrigues & Voluptés , Paris, L'Harmattan, 2012, ch. 2, La vie de Messaline, femme de Claude, pp. 39–64.

- Tatum, W. Jeffrey; The Patrician Tribune: Publius Clodius Pulcher (The University of North Carolina Press, 1999).

- Mudd, Mary; I, Livia: The Counterfeit Criminal. the Story of a Much Maligned Woman (Trafford Publishing, 2012).

- Barrett, Anthony A. (1996). Agrippina: Sex, Power and Politics in the Early Roman Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Klebs, E. (1897–1898). H. Dessau, P. Von Rohden (ed.). Prosopographia Imperii Romani. Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Levick, Barbara (1990). Claudius. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Momigliano, Arnoldo (1934). Claudius: The Emperor and His Achievement. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons.

- Dina Sahyouni, " Le pouvoir critique des modèles féminins dans les Mémoires secrets : le cas de Messaline ", in Le règne de la critique. L'imaginaire culturel des mémoires secrets, sous la direction de Christophe Cave, Paris, Honoré Champion, 2010, pp. 151–160.

- Scramuzza, Vincent (1940). The Emperor Claudius. Harvard University Press.

Sources

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, LX. 14–18, 27–31

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XX. 8; The Wars of the Jews II. 12

- Juvenal, Satires 6, 10, 14

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 10

- Plutarch, Lives

- Seneca the Younger, Apocolocyntosis divi Claudii; Octavia, 257–261

- Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars: Claudius 17, 26, 27, 29, 36, 37, 39; Nero 6; Vitellius 2

- Tacitus, Annals, XI. 1, 2, 12, 26–38

- Sextus Aurelius Victor, epitome of Book of Caesars, 4