Jew's harp

The Jew's harp, also known as jaw harp, juice harp, or mouth harp,[nb 1] is a lamellophone instrument, consisting of a flexible metal or bamboo tongue or reed attached to a frame. Despite the colloquial name the Jew's harp most likely originated in Siberia, specifically in or around the Altai Mountains, and has no relation to the Jewish people.[1]

A typical U.S. Jew's harp | |

| Percussion instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Jew's harp, jaw harp, mouth harp, Ozark harp, juice harp, murchunga, guimbarde, mungiga, vargan, trompe |

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 121.22 (Heteroglot guimbarde (the lamella is attached to the frame)) |

| Related instruments | |

| Sound sample | |

Jew's harps may be categorized as idioglot or heteroglot (whether or not the frame and the tine are one piece); by the shape of the frame (rod or plaque); by the number of tines, and whether the tines are plucked, joint-tapped, or string-pulled.

Characteristics

The frame is held firmly against the performer's parted teeth or lips (depending on the type), using the mouth as a resonator, greatly increasing the volume of the instrument. The teeth must be parted sufficiently for the reed to vibrate freely, and the fleshy parts of the mouth should not come into contact with the reed to prevent damping of the vibrations and possible pain. The note or tone thus produced is constant in pitch, though by changing the shape of the mouth, and the amount of air contained in it (and in some traditions closing the glottis), the performer can cause different overtones to sound and thus create melodies.

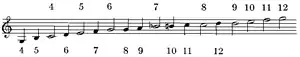

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, "The vibrations of the steel tongue produce a compound sound composed of a fundamental and its harmonics. By using the cavity of the mouth as a resonator, each harmonic in succession can be isolated and reinforced, giving the instrument the compass shown."

"The lower harmonics of the series cannot be obtained, owing to the limited capacity of the resonating cavity. The black notes on the stave show the scale which may be produced by using two harps, one tuned a fourth above the other. The player on the Jew's harp, in order to isolate the harmonics, frames his mouth as though intending to pronounce the various vowels."[2] See: bugle scale.

History

The earliest depiction of somebody playing what seems to be a Jew's harp is a Chinese drawing from the 3rd century BCE, and curved bones discovered in the Shimao fortifications in Shaanxi, China are believed to be the earliest evidence of its existence, dating back to before 1800 BCE.[3][4] Archaeological finds of surviving examples in Europe have been claimed to be almost as old, but those dates have been challenged both on the grounds of excavation techniques, and the lack of contemporary writing or pictures mentioning the instrument.

Although this instrument is used by lackeys and people of the lower class, this does not mean it is not worthy of consideration by better minds ... The trump is grasped while its extremity is placed between the teeth in order to play it and make it sound ... Now one may strike the tongue with the index finger in two ways, i.e., by lifting it or lowering it: but it is easier to strike it by raising it, which is why the extremity, C, is slightly curved, so that the finger is not injured ... Many people play this instrument. When the tongue is made to vibrate, a buzzing is heard which imitates that of bees, wasps, and flies ... [if one uses] several Jew's harps of various sizes, a curious harmony is produced.

Etymology

There are many theories for the origin of the name jew's harp. The apparent reference to Jewish people is especially misleading since it "has nothing to do with the Jewish people; neither does it look like a harp in its structure and appearance".[6] In Sicilian it is translated as Marranzanu or Mariolu; both of which are derogatory terms for Jewish people and also found in Italian[7] and Spanish.[8] In German, it is known as Maultrommel, which roughly translates as 'mouth drum'.[6] The name "Jew's Harp" first appears in 1481 in a customs account book under the name "Jue harpes".[9] The "jaw" variant is attested at least as early as 1774[10] and 1809,[11] the "juice" variant appeared only in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

It has also been suggested that the name derives from the French jeu-trompe meaning 'toy trumpet'.[12] The current French word for the instrument is guimbarde. Wedgwood, an English etymologist, wrote in 1855 that the derivation from jeu harpe opposes the French idiom, where "if two substantives are joined together, the qualifying noun is invariably the last.[13] He refers to the jeu harpe derivation, but not to the jeu tromp derivation.

Both theories—that the name is a corruption of jaws or jeu—are described by the OED as "lacking any supporting evidence."[14] The OED says that, "more or less satisfactory reasons may be conjectured: e.g. that the instrument was actually made, sold, or imported to England by Jewish people, or purported to be so; or that it was attributed to Jewish people, suggesting the trumps and harps mentioned in the Bible, and hence considered a good commercial name."[15] The OED also states that "the association of the instrument with Jewish people occurs, so far as is known, only in English."[14] However, the term is also used in Danish as jødeharpe.[16]

Manufacture

Manufacture of Indian morchang

Indian morchangs are made in many metals but mainly in brass, iron, copper and silver. Different types of construction art are used for the construction of Morchang in each metal.

Brass

Brass murchangs are manufactured[17] from ancient Indian manufacturing style brass metal casting. Brass molding is a process of shaping brass, into desired shapes using a mold. The brass is heated to a molten state and then poured or forced into the mold, where it cools and solidifies into the desired shape. Brass molding is often used to create intricate or complex shapes.

Use

Cambodian music

The angkouch (Khmer: អង្គួច) is a Cambodian Jew's harp.[18] It is a folk instrument made of bamboo and carved into a long, flat shape with a hole in the center and the tongue across the hole.[19] There is also a metal variety, more round or tree-leaf shaped.[19] It may also have metal bells attached.[19] The instrument is both a wind instrument and percussion instrument.[18][19] As a wind instrument, it is placed against the mouth, which acts as a resonator and tool to alter the sound.[19] Although mainly a folk instrument, better-made examples exist.[19] While the instrument was thought to be the invention of children herding cattle, it is sometimes used in public performance, to accompany the Mahori music in public dancing.[19]

Indian Classical music

The instrument is used as part of the rhythm section in various styles of Indian folk and classical music. Most notably the Morsing in the Carnatic music of South India,[20] or the Morchang in the lok geet (folk music) of Rajasthan.

Murchunga

In Nepal, one type of Jew's harp is named the murchunga (Nepali: मुर्चुङ्गा).[21] It is very similar to an Indian morsing or morchang in that the tongue (or twanger) extends beyond the frame, thus giving the instrument more sustain.[22]

Binayo

The binayo (Nepali बिनायो बाजा) is a bamboo Jew's harp, in the Kiranti musical tradition from Malingo. It is popular in the Eastern Himalayan region of Sikkim, Darjeeling Nepal and Bhutan. It is a wind instrument played by blowing the air without tuning the node with fingers. The binayo is six inches long and one inch in width.[23]

Turkic traditional music

Kyrgyz music

The temir komuz is made of iron, usually with a length of 100–200 mm and with a width of approximately 2–7 mm. The range of the instrument varies with the size of the instrument but generally hovers around an octave span. The Kyrgyz people are exceptionally proficient on the instrument and it is quite popular among children, although some adults continue to play the instrument. A national artist from the Kyrgyz Republic performs on the instrument. Twenty Kyrgyz girls have played in a temir komuz ensemble on the stage of the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. Temir komuz pieces were notated by Aleksandr Zataevich in two or three parts. An octave drone is possible, or even an ostinato alternating the fifth step of a scale with an octave.[24]

Turkish music

In Turkish, the Jew's harp is called as ağız kopuzu.[25][26] The Jew's harp traditionally used in Turkish folk songs from Anatolia has fallen out of use with time.[27][28] Modern renditions of Turkish folk songs with the Jew's harp have been done by artists such as Senem Diyici in the song 'Dolama Dolamayı' and Ravan Yuzkhan.

Sindhi music

In Sindhi the Jew's harp is called changu (چنگُ). In Sindhi music, it can be an accompaniment or the main instrument. One of the most famous players is Amir Bux Ruunjho.[29]

Sicilian music

In Sicily, the Jew's harp is commonly known as marranzanu, but other names include angalarruni, calarruni, gangalarruni, ganghilarruni, mariolu, mariolu di fera, marranzana, and ngannalarruni.[30][31]

Austrian Jew's harp playing

Austrian Jew's harp music uses typical Western harmony. The UNESCO has included Austrian Jew's harp playing in its Intangible Cultural Heritage list.[32]

In Austria, the instrument is known as Maultrommel (the literal translation is 'mouth drum').

Western classical music

Early representations of Jew's harps have appeared in Western churches since the fourteenth century.[33]

The Austrian composer Johann Albrechtsberger—chiefly known today as a teacher of Beethoven—wrote seven concerti for Jew's harp, mandora, and orchestra between 1769 and 1771. Four of them have survived, in the keys of F major, E-flat major, E major, and D major.[34] They are based on the special use of the Jew's harp in Austrian folk music.

In the experimental period at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century there were very virtuoso instrumentalists on the mouth harp. Thus, for example, Johann Heinrich Scheibler was able to mount up to ten mouth harps on a support disc. He called the instrument "Aura". Each mouth harp was tuned to different basic tones, which made even chromatic sequences possible.

— Walter Maurer, translated from German[35]

Well known performer Franz Koch (1761–1831), discovered by Frederick the Great, could play two Jew's harps at once, while the also well known performer Karl Eulenstein (1802—1890), "invented a system of playing four at once, connecting them by silken strings in such a way that he could clasp all four with the lips, and strike all the four springs at the same time".[36]

The American composer Charles Ives wrote a part for Jew's harp in the Washington's Birthday movement of A Symphony: New England Holidays.[37]

Western music

The Jew's harp has been used occasionally in rock and country music. For example:

- Canned Heat's multi-part piece "Parthenogenesis" from their Living the Blues album.[38][39]

- Black Sabbath – "Sleeping Village"[40]

See also

- Jew's harp music

- Music of Central Asia

- Traditional music of Sicily

- Berimbau

- Đàn môi, another kind of Jew's harp from Vietnam

- Gogona, a similar instrument played by Assamese people (especially women) while singing and dancing Bihu

- Karinding, a Sundanese traditional musical instrument from West Java and Banten, Indonesia

- Kouxian, the Chinese version

- Kubing, a bamboo Jew's harp from the Philippines

- Morsing, Carnatic Jew's harp

- Mukkuri, a traditional bamboo instrument of the Ainu of Japan, similar to a Jew's harp

- Musical bow, a one-string harp that is played with mouth resonance

- Piperheugh, a village in which trumps were once made

Notes

- Other names for the instrument include ağız kopuzu (Turkey), angkouch (Cambodia), brumle (Czechoslovakia), changu (Sindh), đàn môi (Vietnam), doromb (Hungary), drumla (Poland), drymba (Ukraine), gewgaw, guimbard (France), guimbarda (Catalan), gogona (Assam), karinding (Sudanese), khomus (Siberia), kouxian (China), kubing (Philippines), marranzano (Sicily, Italy), Maultrommel (Austria and Germany), mondharp/munnharpe (Norway), morchang (Rajasthan), morsing (South India), mukkuri (Japan), mungiga, murchunga/binayo (Nepal), Ozark harp (United States), parmupill (Estonia), trump (Scotland), and vargan (Russia).

References

Citations

- Katz, Brigit (23 January 2018). "This Recently Discovered 1,700-Year-Old Mouth Harp Can Still Hold a Tune". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 5 July 2023. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- Schlesinger 1911.

- "Sicilian Item of the day:Marranzano". Siciliamo (blog). 2007-08-10. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- Larmer, Brook (2020). "Mysterious carvings and evidence of human sacrifice uncovered in ancient city". National Geographic.

- Fox (1988), p.45-8.

- "Jew's harp origin history | Glazyrin's jew's harps". 18 April 2019.

- "Etimologia : Marrano".

- "Léxico - Etimologias - Origen de las Palabras - Marrano".

- WRIGHT, MICHAEL (2020). JEWS-HARP IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND. [S.l.]: ROUTLEDGE. ISBN 978-0-367-59749-8. OCLC 1156990682.

- Miscellaneous and Fugitive pieces, vol. 3, Johnson et al. 1774

- Pegge's Anonymiana, 1818, p. 33

- Timbs, John (1858). Things Not Generally Known: Popular Errors Explained & Illustrated. p. 61.

- Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1855). "On False Etymologies". Transactions of the Philological Society (6): 63.

- "Université Laval - Déconnexion".

- "Jews' trump, Jew's-trump". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1989.

- "Jødeharpe - Den Danske Ordbog".

- Ancient building style of jews harp | morchang | morsing | best jews harp | best morchang |, retrieved 2023-01-27

- Poss, M.D. "Cambodian Bamboo Jew's Harps". mouthmusic.com. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

... these bamboo Jew's harps are easy to hold and may be longer lasting due to being made of thicker material than many other similar instruments. Held against the lips, they are easy to play and offer the same full, percussive sound as the "Kubings."

- Khean, Yun; Dorivan, Keo; Lina, Y; Lenna, Mao. Traditional Musical Instruments of Cambodia (PDF). Kingdom of Cambodia: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. pp. 146–147.

- (1999). South Asia : The Indian Subcontinent. Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 5. Publisher: Routledge; Har/Com. ISBN 978-0-82404946-1.

- "Photo Gallery". Kathmandu: Nepali Folk Musical Instrument Museum.

- Nikolova, Ivanka; Davey, Laura; Dean, Geoffrey, eds. (2000). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Musical Instruments. Cologne: Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. pp. 94–101.

- "Folk musical Instruments Of Nepal". Schoolgk.com. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- Slobin, Mark (1969). Kirgiz Instrumental Music. Theodore Front Music. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-614-16459-6. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- "Hopeful Sound of the Wind: Mouth Harp". Türktoyu - Voyage To The Turkic World. Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- Ayci̇l, Serkan; Çubukcu, Gökçin (2022-03-30). "TÜRK MÛSİKÎ ÇALGILARININ VE ROMAN KÜLTÜRÜNDEKİ ÇALGI GELENEĞİNİN POSTA PULLARI ÜZERİNDEN DEĞERLENDİRİLMESİ". Sanat Dergisi (in Turkish) (39): 44–57. ISSN 1302-2938.

- Apel, Willi (2003-11-28). The Harvard Dictionary of Music: Fourth Edition. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01163-2.

- "Ağız Kopuzu Sanatı". aksaray.ktb.gov.tr. Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- sindhi alghozo. YouTube. 9 July 2009. Archived from the original on 2021-11-11. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- Dieli, Art (May 29, 2011). "Sicilian Vocabulary". Dieli. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- http://siciliamo.blogspot.com/2007/08/sicilian-item-of-day-marranzano.html. Siciliamo (blog). 2007-08-10. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- Intangible Cultural Heritage in Austria: Jew's Harp Playing in Austria (archived version at the Internet Archive from October 3, 2015)

- For example, there is a carving of a centaur playing a jaw harp in the Basel Münster. Musiconis Database. Université Paris-Sorbonne. http://musiconis.huma-num.fr/fiche/120/Hybride+jouant+de+la+guimbarde. Accessed January 5, 2018.

- Albrechtsberger: Concerto for Jew's Harp, Amazon CD Listing (Munich Chamber Orchestra, December 19, 1992, for more see: http://www.fondationlaborie.com/images/stories/notesdeprogramme/lc08_en.pdf)

- Maurer, Walter (1983). Accordion: Handbuch eines Instruments, seiner historischen Entwicklung un seiner Literature, p.19. Vienna: Edition Harmonia.

- Burnley, James (1886). The Romance of Invention: Vignettes from the Annals of Industry and Science, p.335. Cassell. [ISBN unspecified].

- Fox, Leonard (1988). The Jew's Harp: A Comprehensive Anthology. Associated University Presses, Inc. p. 33. ISBN 9780838751169. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- Graves, Tom (30 April 2015). Louise Brooks, Frank Zappa, & Other Charmers & Dreamers. BookBaby. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-942531-07-4. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- Winters, Rebecca Davis (2007). Blind Owl Blues. Blind Owl Blues. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-615-14617-1. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- Wells, David (2009). "Black Sabbath (1970)". Black Sabbath (CD Booklet). Black Sabbath. Sanctuary Records Group.

General and cited references

- Alekseev, Ivan, and E. I. [i.e. Egor Innokent'evich] Okoneshnikov (1988). Iskusstvo igry na iakutskom khomuse. IAkutsk: Akademiia nauk SSSR, Sibirskoe otd-nie, IAkutskii filial, In-t iazyka, lit-ry i istorii.

- Bakx, Phons (1992). De gedachtenverdrijver: de historie van de mondharp. Hadewijch wereldmuziek. Antwerpen: Hadewijch; ISBN 90-5240-163-2.

- Boone, Hubert, and René de Maeyer (1986). De Mondtrom. Volksmuziekinstrumenten in Belgie en in Nederland. Brussel: La Renaissance du Livre.

- Crane, Frederick (1982). "Jew's (jaw's? jeu? jeugd? gewgaw? juice?) harp." In: Vierundzwanzigsteljahrschrift der Internationalen Maultrommelvirtuosengenossenschaft, vol. 1 (1982). With: "The Jew's Harp in Colonial America," by Brian L. Mihura.

- Crane, Frederick (2003). A History of the Trump in Pictures: Europe and America. A special supplement to Vierundzwanzigsteljahrsschrift der Internationalen Maultrommelvirtuosengenossenschaft. Mount Pleasant, Iowa: [Frederick Crane].

- Dournon-Taurelle, Geneviève, and John Wright (1978). Les Guimbardes du Musée de l'homme. Preface by Gilbert Rouget. Published by the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle and l'Institut d'ethnologie.

- Emsheimer, Ernst (1941). "Über das Vorkommen und die Anwendungsart der Maultrommel in Sibirien und Zentralasien". In: Ethnos (Stockholm), nos 3–4 (1941).

- Emsheimer, Ernst (1964). "Maultrommeln in Sibirien und Zentralasien." In: Studia ethnomusicologica eurasiatica (Stockholm: Musikhistoriska museet, pp. 13–27).

- Fox, Leonard (1984). The Jew's Harp: A Comprehensive Anthology. Selected, edited, and translated by Leonard Fox. Charleston, South Carolina: L. Fox.

- Fox, Leonard (1988). The Jew's Harp: A Comprehensive Anthology. Selected, edited, and translated by Leonard Fox. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press; London: Associated University Presses; ISBN 0-8387-5116-4.

- Gallmann, Matthew S. (1977). The Jews Harp: A Select List of References With Library of Congress Call Numbers. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, Archive of Folk Song.

- Gotovtsev, Innokenty. New Technologies for Yakut Khomus. Yakutsk.

- Kolltveit, Gjermund (2006). Jew's Harps in European Archaeology. BAR International series, 1500. Oxford: Archaeopress; ISBN 1-84171-931-5.

- Mercurio, Paolo (1998). Sa Trumba. Armomia tra telarzu e limbeddhu. Solinas Edition, Nuoro (IT).

- Plate, Regina (1992). Kulturgeschichte der Maultrommel. Orpheus-Schriftenreihe zu Grundfragen der Musik, Bd. 64. Bonn: Verlag für Systematische Musikwissenschaft; ISBN 3-922626-64-5.

- Mercurio, Paolo (2013). Gli Scacciapensieri Strumenti Musicali dell'Armonia Internazionali, Interculturali, Interdisciplinari. Milano; ISBN 978-88-6885-391-4.

- Schlesinger, Kathleen (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 411.

- Shishigin, S. S. (1994). Igraite na khomuse. Mezhdunarodnyi tsentr khomusnoi (vargannoi) muzyki. Pokrovsk: S.S. Shishigin/Ministerstvo kul'tury Respubliki Sakha (IAkutiia). ISBN 5-85157-012-1.

- Shishigin, Spiridon. Kulakovsky and Khomus. Yakutia.

- Smeck, Roy (1974). Mel Bay's Fun With the Jaws Harp. ISBN 9780871664495

- Wright, Michael (2008). "The Jew's Harp in the Law, 1590–1825". Folk Music Journal 9.3 pp. 349–371; ISSN 0531-9684. JSTOR 25654126.

- Wright, Michael (2015). The Jew's Harp in Britain and Ireland. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate; ISBN 978-1-4724-1413-7.

- Yuan, Bingchang, and Jizeng Mao (1986). Zhongguo Shao Shu Min Zu Yue Qi Zhi. Beijing: Xin Shi Jie Chu Ban She: Xin Hua Shu Dian Beijing Fa Xing Suo Fa Xing; ISBN 7-80005-017-3.

External links

- The Jew's Harp Guild

- How to play and make jew's harp

- How to play the jew's harp (instructions with sound examples and remarks on the functioning of Jew's harps)

- A page on guimbardes from Pat Missin's free reed instrument website

- Demir-xomus (Tuvan Jew's Harp) Demos, photos, folktale, and text