Ventura County, California

Ventura County (/vɛnˈtʊərə/ ⓘ) is a county located in the southern part of the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 843,843.[10][11] The largest city is Oxnard, and the county seat is the city of Ventura.[12]

Ventura County | |

|---|---|

| County of Ventura | |

.jpg.webp)    Images, from top down, left to right: Ventura City Hall in Old Town Ventura, Ojai Arcade in Ojai, a view of Camarillo, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, Point Mugu | |

Flag  Seal | |

Interactive map of Ventura County | |

Location in the state of California | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Region | Greater Los Angeles California Central Coast |

| Created | March 22, 1872[1] |

| Established | January 1, 1873[2] |

| Named for | Mission San Buenaventura, which was named after Saint Bonaventure |

| County seat | Ventura |

| Largest city | Oxnard (population) Thousand Oaks (area) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–CEO |

| • Body | Board of Supervisors [3][4][5][6][7] |

| • Chair | Matt LaVere (N.P.) |

| • Vice Chair | Kelly Long (N.P.) |

| • Board of Supervisors[8] | |

| • Chief executive officer | Sevet Johnson |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,208 sq mi (5,720 km2) |

| • Land | 1,843 sq mi (4,770 km2) |

| • Water | 365 sq mi (950 km2) |

| Highest elevation | 8,835 ft (2,693 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 843,843 |

| • Density | 458/sq mi (177/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific Time Zone) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (Pacific Daylight Time) |

| Area codes | 805/820, 818/747 |

| FIPS code | 06-111 |

| GNIS feature ID | 277320 |

| Congressional districts | 24th, 26th, 32nd |

| Website | www |

Ventura County comprises the Oxnard–Thousand Oaks–Ventura, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is part of the Greater Los Angeles area (Los Angeles-Long Beach, CA Combined Statistical Area). It is also considered the southernmost county along the California Central Coast.[13]

Two of the Channel Islands are part of the county: Anacapa Island, which is the most visited island in Channel Islands National Park,[14] and San Nicolas Island.

History

Pre-colonial period

Ventura County was historically inhabited by the Chumash people, who also settled much of Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo Counties, with their presence dating back 10,000–12,000 years.[15][16] The Chumash were hunter-gatherers, fishermen, and also traders with the Mojave, Yokuts, and Tongva Indians.[17] The Chumash are also known for their rock paintings and for their great basketry. Chumash Indian Museum in Thousand Oaks has several reconstructed Chumash houses (‘apa) and there are several Chumash pictographs in the county, including the Burro Flats Painted Cave in Simi Valley. The plank canoe, called a tomol in Chumash, was important to their way of life. Canoe launching points on the mainland for trade with the Chumash of the Channel Islands were located at the mouth of the Ventura River, Mugu Lagoon and Point Hueneme.[18][19] This has led to speculations among archeologists of whether the Chumash could have had a pre-historic contact with Polynesians.[20][21] According to diachronic linguistics, certain words such as tomolo’o (canoe) could be related to Polynesian languages. The dialect of the Chumash language that was spoken in Ventura County was Ventureño.[22]

Several place names in the county has originated from Chumash, including Ojai, which means moon,[23] and Simi Valley, which originates from the word Shimiyi and refers to the stringy, thread-like clouds that typify the region.[24] Others include Point Mugu from the word Muwu (meaning “beach”), Saticoy from the word Sa’aqtiko’y (meaning “sheltered for the wind”), and Sespe Creek from the word S’eqp’e (meaning “kneecap”).[25]

Spanish period

In October 1542, the expedition led by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo anchored in an inlet near Point Mugu; its members were the first Europeans to arrive in the area that would become Ventura County.[26]

Active occupation of California by Spain began in 1769. Gaspar de Portolà led a military expedition by land from San Diego to Monterey, passing through Ventura County in August of that year. A priest with the expedition, Father Juan Crespí, kept a journal of the trip and noted that the area was ideal for a mission to be established and it was a "good site to which nothing is lacking".[27] Also on this expedition was Father Junípero Serra, who later founded a mission on this site.

On March 31, 1782, the Mission San Buenaventura was founded by Father Serra.[28] It is named after Saint Bonaventure, one of the early intellectual founders of the Franciscan order. The town that grew up around the mission was originally named San Buenaventura (and retains the name officially), it has been known as Ventura since 1891.[29]

In the 1790s, the Spanish Governor of California began granting land concessions to Spanish Californians who were often retiring soldiers. These concessions were known as ranchos and consisted of thousands of acres of land that were used primarily as ranch land for livestock. In Ventura County, Rancho Simi was granted in 1795 and Rancho El Conejo in 1802.[30] Fernando Tico was granted Ojai and part of Ventura by Gov. Alvarado.

Mexican period

In 1822, California was notified of Mexico's independence from Spain and the Governor of California, the Junta, the military in Monterey and the priests and neophytes at Mission San Buenaventura swore allegiance to Mexico on April 11, 1822. California land that had been vested in the King of Spain was now owned by the nation of Mexico.

By the 1830s, Mission San Buenaventura was in a decline with fewer neophytes joining the mission. The number of cattle owned by the mission dropped from first to fifteenth ranking in the California Missions.[32] The missions were secularized by the Mexican government in 1834. The Mexican governors began granting land rights to Mexican Californians, often retiring soldiers. By 1846, there were 19 rancho grants in Ventura County.[33] In 1836, Mission San Buenaventura was transferred from the Church to a secular administrator. The natives who had been working at the mission gradually left to work on the ranchos. By 1839, only 300 Indians were left at the Mission and it slipped into neglect.[34]

Several outhouses dating back to the 1800s were discovered in July 2007, at a site that had been cleared to prepare for development. The area proved to be a treasure trove for archaeologists who braved the lingering smell in the dirt to uncover artifacts that showed heavy utilization by mission inhabitants, Indians, early settlers and Spanish and Mexican soldiers.[35]

American period

The Mexican–American War began in 1846 but its effect was not felt in Ventura County until 1847. In January of that year, Captain John C. Frémont led the California Battalion into San Buenaventura to find that the Europeans had fled, leaving only the Indians in the Mission. Fremont and the Battalion continued south to sign the Treaty of Cahuenga with General Andrés Pico. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo formally transferred California to the United States in 1848.[36]

By 1849, a constitution had been adopted for the California territory. The new Legislature met and divided the pending state into 27 counties. At the time, the area that would become Ventura County was the southern part of Santa Barbara County.[37]

The 1860s brought many changes to the area. A drought caused many of the ranchos to experience financial difficulties and most were divided, sub-divided and sold. Large sections of land were bought by eastern capitalists based on favorable reports of petroleum deposits. A United States Post Office was opened at Mission San Buenaventura in 1861. On April 1, 1866, the town of San Buenaventura was incorporated, becoming the first officially recognized town in what would become Ventura County.[38]

On January 1, 1873, Ventura County was officially split from Santa Barbara County, bringing a flurry of change. That same year, a courthouse and wharf were built in San Buenaventura. A bank was opened and the first public library was created. The school system grew, with the first high school opening in 1890.[39]

Other towns were being established in the county. A plan for Hueneme (later Port Hueneme) was recorded in 1874, and Santa Paula's plan was recorded in 1875. Along the banks of the Santa Clara River, the township of New Jerusalem (which would eventually be named El Rio) was founded in 1875 by the owner of general store named Simon Cohen who became its first postmaster and banker in 1882.[40] The community of Nordhoff (later renamed Ojai) was started in 1874.[41] Bardsdale, Fillmore, Piru, and Montalvo were established in 1887.[42] 1892 saw Simi (later Simi Valley), Somis, Saticoy, and Moorpark. Oxnard was a latecomer, not being established until 1898.[43]

The Southern Pacific Railroad laid tracks through San Buenaventura in 1887. For convenience in printing their timetables, Southern Pacific shortened San Buenaventura to Ventura. The Post Office soon followed suit. While the city remains officially known as San Buenaventura, it is more commonly referred to as Ventura.[44] The rail line to Northern California originally went through Saugus, Fillmore and Santa Paula, providing a boom to those communities along the line. In 1905, Tunnel #26 was completed between Chatsworth and Corriganville near Simi Valley, shortening the rail route. At a length of 7,369 feet (2,246 m), Tunnel #26 was the longest tunnel ever constructed in its day.[45] This tunnel joined to the railroad spur coming the other direction from Montalvo through Camarillo, Moorpark and Simi Valley, making the contemporary main line used today. One stop along the way, at a 90-degree turn, was at a sugar beet processing factory. The factory bore the name of its absentee owners, the Oxnard Brothers. A small community of farm and factory workers grew near the train stop. That community, now bearing the name of the factory shortened to the one word train stop Oxnard, has become the largest city in Ventura County.[46][47]

Oil has been known in Ventura County since before the arrival of the Europeans, as the native Chumash people used tar from natural seeps as a sealant and waterproofing for baskets and canoes. In the 1860s, several attempts were made to harvest the petroleum products under Ventura County but none were financially successful, and the oil speculators eventually changed from oil to land development. In 1913, oil exploration began in earnest, with Ralph Lloyd obtaining the financial support of veteran oil man Joseph B. Dabney. Their first well, named "Lloyd No. 1", was started on January 20, 1914. The well struck oil at 2,558 feet (780 m) but was destroyed when it went wild. Other wells met a similar fate, until 1916, when a deal was struck with the Shell Oil Company. 1916 was the year that the large South Mountain Oil Field was discovered; other deals followed with General Petroleum in 1917 and Associated Oil Company in 1920. At its peak, the largest oil field in the county, the Ventura Avenue oilfield, discovered in 1919 in the hills north of Ventura, was producing 90,000 barrels (14,000 m3) of oil a day, with annual production of over 1.5 million barrels. More oil fields came online in the 1920s and 1930s, with the Rincon field, the second largest, in 1927, and the adjacent San Miguelito in 1931.[48][49]

In the early hours of the morning of March 12–13, 1928, the St. Francis Dam collapsed, sending nearly 12,500 million U.S. gallons (47 gigaliters) of water rushing through the Santa Clarita Valley killing as many as 600 people,[50] destroying 1,240 homes and flooding 7,900 acres (32 km2) of land, devastating farm fields and orchards.[51] This was the single largest disaster to strike Ventura County and the second largest, in terms of lives lost, in the state.

Modern period

Ventura County can be separated into two major parts, East County and West County, which are divided by the Conejo Grade.[52] East County consists of all cities east of the Conejo Grade. Geographically East County is the end of the Santa Monica Mountains, in which the Conejo Valley is located, and where there is a considerable increase in elevation. Communities which are considered to be in the East County are Thousand Oaks, Newbury Park, Lake Sherwood, Hidden Valley, Santa Rosa Valley, part of Westlake Village, Oak Park, Moorpark, and Simi Valley. A majority of these communities are in the Conejo Valley.

West County, which is everything west of the Conejo Grade, consists of communities such as Camarillo, Oxnard, Somis, Point Mugu, Port Hueneme, Ventura, Ojai, Santa Paula, and Fillmore. West County consists of some of the first developed cities in the county. The largest beach communities are located in West County on the coastline of the Channel Islands Harbor.

Starting in the mid-20th century, there was a large growth in population in the East County, moving from the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles and out into the Conejo and Simi Valleys. Part of the Conejo Valley is situated in Los Angeles County. This part consists of Calabasas, Hidden Hills, Agoura Hills, Agoura, and Westlake Village. The other half of the Conejo Valley, which belongs to Ventura County, consists of Lake Sherwood, Hidden Valley, Oak Park, Thousand Oaks, and Newbury Park, which was formerly an unincorporated area that is now the most westerly part of Thousand Oaks. Many working-class people migrated to this area during the 1960s and 1970s out of East and Central Los Angeles. As a result, there was a large growth in population into the Conejo Valley and into Ventura County through the U.S. Route 101 corridor. Making the U.S. 101 a full freeway in the 1960s, and the expansions that followed, helped make commuting to Los Angeles easier and opened the way for development westward. The communities that have seen the most substantial development are Calabasas, Hidden Hills, Agoura Hills, Westlake Village, Thousand Oaks, and Newbury Park. The neighboring East County area of Simi Valley saw its already considerable population of nearly 60,000 inhabitants in 1970 grow to over 100,000 over the following two decades.

Development moved farther down the U.S. 101 corridor and sent population rising in West County cities as well. The largest population growth there has been in Camarillo, Oxnard, and Ventura. Development in the East County and along the US 101 corridor is rare today, because most of these cities, such as Thousand Oaks and Simi Valley, are approaching build-out. Although the area still has plenty of open space and land, almost all of it is in greenbelts between the cities.[53] Because of this, its private low-key location, its country feel, and its proximity to Los Angeles, the Conejo Valley area has become a very attractive place to live. Like most areas of Ventura County, it once had relatively inexpensive real estate, but prices have risen sharply. For example, real estate in Newbury Park has increased in price by more than 250% in the last 10 years.

Thomas Fire

The Thomas Fire was a massive wildfire that affected Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties, and one of multiple wildfires that ignited in Southern California in December 2017. It burned approximately 281,893 acres (440 sq mi; 114,078 ha), becoming the largest wildfire in modern California history, before it was fully contained on January 12, 2018.[54]

The Thomas Fire destroyed at least 1,063 structures, while damaging 280 others;[55] and the fire caused over $2.176 billion (2018 USD) in damages,[56][57] including more than $204.5 million in suppression costs, becoming the seventh-most destructive wildfire in state history.[58] The agriculture industry suffered at least $171 million in losses due to the Thomas Fire.[57][59][60] Southern California Edison paid the county over $11 million in claims related to damages and costs since its equipment was likely associated with one ignition point of the fire near Santa Paula.[61]

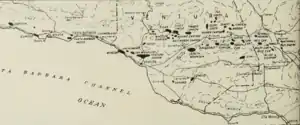

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 2,208 square miles (5,720 km2), of which 1,843 square miles (4,770 km2) is land and 365 square miles (950 km2) (16.5%) is water.[63][64]

Parts of the county are on the Oxnard Plain which includes the cities of Oxnard, Camarillo, Port Hueneme and much of Ventura. Other cities and communities lie in the intermountain valleys of the Transverse Range. The Santa Clara River Valley is the most prominent valley, while other valleys include Conejo Valley, Simi Valley, Santa Rosa Valley, Tierra Rejada Valley and Las Posas Valley. Other parts of the county are on small coastal mountains, such as the Santa Ynez Mountains, Simi Hills, Santa Monica Mountains and the Piru Mountains. Most of the population of Ventura County lives in the southern portion of the county. The major population centers are the Oxnard Plain and the Simi and Conejo Valleys. In local media, the county is usually split between the eastern portion, generally associated with the San Fernando Valley, and the western portion, often referred to as “Oxnard-Ventura". To the east is Los Angeles County.

Because the total amount of precipitation is small, conserving water and obtaining water from additional sources outside of Ventura County are vital concerns.[65] The climate, though mostly mild and dry, varies because of the variations in topography through for instance differences in elevation and physical geography. The Santa Clara River is the principal waterway. Lake Casitas, an artificial reservoir, is the largest body of water.

The highest peaks in the county include Mount Pinos (8,831 ft; 2,692 m), Frazier Mountain (8,017 ft; 2,444 m), and Reyes Peak (7,525 ft; 2,294 m) in the Transverse Ranges. The uplands are well-timbered with coniferous forests, and receive plentiful snow in the winter. Mount Pinos is sacred to the Chumash Indians. It is known to them as Iwihinmu, and was considered to be the center of the universe; being the highest peak in the vicinity, it has unimpeded views in three directions.[66]

The USDA Economic Research Service rated Ventura County the most desirable county to live in the 48 contiguous states, using six metrics of climate ("mild, sunny winters, temperate summers, low humidity"), topographic variation, and access to water, "that reflect environmental qualities most people prefer."[67]

Physical geography

There are 555,953 acres (224,986 ha) outside of national forest land in Ventura County, which means that 53 percent of the county's total area is made up of national forest. Of the land outside of national forest land, approximately 59 percent is agricultural and 17.5 percent urban.[62] North of Highway 126, the county is mountainous and mostly uninhabited, and contains some of the most unspoiled, rugged and inaccessible wilderness remaining in southern California. Most of this land is in the Los Padres National Forest, and includes the Chumash Wilderness in the northernmost portion, adjacent to Kern County, as well as the large Sespe Wilderness and portions of both the Dick Smith Wilderness and Matilija Wilderness (both of these protected areas straddle the line with Santa Barbara County). All of the wilderness areas are within the jurisdiction of Los Padres National Forest.

The coastal plain was formed by the deposition of sediments from the Santa Clara River and from the streams of the Calleguas-Conejo drainage system. It has a mean elevation of fifty feet (15 m), but at points south of the Santa Clara River, the elevation is as much as 150 feet (46 m), and at points north of the river, as much as 300 feet (91 m). The coastal plain is generally known as the Oxnard Plain with the part that centers on Camarillo lying east of the Revelon Slough is called Pleasant Valley. Most of the arable land in the county is found on the coastal plain. Small coastal mountains rim Ventura County on its landward side. They range in elevation from 50 feet (15 m) along the coast south of the coastal plain, to about 3,100 feet (940 m) in the Santa Monica Mountains. The Santa Ynez Mountains, the Topatopa Mountains, and the Piru Mountains make up the northern boundary of the coastal plain, the Santa Susana Mountains are alongside the eastern boundary of the county, and the Simi Hills and the Santa Monica Mountains are along the southern border with Los Angeles County.[68] South Mountain and Oak Ridge are low and long mountains that separate Santa Clara Valley from the Las Posas Valley and Simi Valley. The Camarillo Hills and the Las Posas Hills extend from Camarillo to Simi Valley and separate the Las Posas-Simi area from the Santa Rosa Valley and Tierra Rejada Valley.[69]

The intermountain valley of the Santa Clara River is the most prominent valley in the county and trends east–southwest. The Santa Clara River drains an area of 1,605 square miles (4,160 km2) and flows from its headwaters in Los Angeles to where it empties into the Pacific. Its principal tributaries are Piru Creek, Santa Paula Creek, and Sespe Creek. The valley of the Ventura River is a narrow valley north of Ventura. Ojai Valley is connected to the Ventura River Valley by San Antonio Creek. The small Upper Ojai Valley, east of Ojai Valley and 300 to 500 feet (91 to 152 m) higher, drains to the Ventura River on the west and to Santa Paula Creek on the east. Ojai and Upper Ojai Valleys are surrounded by mountains and are rich agricultural areas. The Ventura River flows south and drains an area of 226 square miles (590 km2). Over South Mountain and Oak Ridge, south of the Santa Clara River, are Las Posas Valley and Simi Valley. Las Posas Valley extends eastward from the Oxnard Plain almost to Simi Valley, which is in the east end of Ventura County. The city of Simi Valley is bounded on the east by the Santa Susana Mountains and on the south by the Simi Hills. To the south, over the Camarillo- and Las Posas Hills, are Santa Rosa- and Tierra Rejada Valleys, which extend from Camarillo eastward for ten miles (16 km). In the hills south of Santa Rosa Valley is the broad Conejo Valley. Santa Rosa Valley, Conejo Valley, Simi Valley, and Tierra Rejada Valley are drained by Calleguas Creek and its principal tributary, Conejo Creek. These creeks originate in the Santa Susana and Santa Monica Mountains.[65]

The county's diverse 43-mile (69 km)[70] coastline features a variety of terrain. There are many State beaches: Emma Wood, San Buenaventura, McGrath, and Mandalay State Beach. Other beaches include Channel Islands Beach, Solimar Beach, Oxnard Beach Park, and Silver Strand Beach. While Point Mugu State Park is known for its steep coastal terrain with little beach access, nearby County Line Beach in the south coast community of Solromar is part of the fabled Malibu coastline. Ventura County has plenty of other surf spots along the coast including the notable surf spot, Rincon Point, on the Santa Barbara County-line.

The Channel Islands in Ventura County are Anacapa and San Nicholas Islands.

Climate

Ventura County has a considerable range in climate because of differences in topography between one part of the county and another. Rainfall is limited in summer and crops have to be irrigated. The average annual temperature is near 60 °F at low elevations near the ocean, in the 50s over most of the northern two-thirds of the county, and less than 45 °F in the Topatopa Mountains. The annual range in temperature is between 70 °F and 80 °F on the Coastal Plain and as much as 100 °F in the interior. For July, the average maximum temperature is between 70 °F and 80 °F on the Coastal Plain but exceeds 90 °F in the upper part of the Ventura- and Cuyama River Valleys. For January, the average minimum temperature is near 40 °F on the coast but in the lower 30s and upper 20s in the northern parts of Ventura County. No temperature data are available for the highest point in the county, Mount Pinos. The length of the growing season ranges more than 300 days near the coast to less than 175 days in the coldest part in northern Ventura County. In both the northern and southern ends of the county, the annual precipitation totals between ten and fifteen inches. In the Topatopa Mountains, the annual total is more than thirty-three inches. The drier parts of the county get less than five inches of rain annually, and the higher and wetter parts get more than 60 inches annually. Measureable amounts of rainfall in Ventura County are reported on thirty to thirty-five days annually, and half an inch or more on six to twelve days annually. In the northern parts of Ventura County, snowfall averages five inches or more per year, and along the northern border and Mount Pinos, more than twenty inches.[69]

Air quality

Automobile emissions account for most of the air pollution. Other sources include chemical plants, gasoline stations, paint and cleaning products.[71]

Adjacent counties

- Santa Barbara County, California — west

- Kern County, California — north

- Los Angeles County, California — east

National protected areas

Rivers

Rivers in Ventura County include:

- Los Sauces Creek

- Madrianio Creek

- Padre Juan Canyon

- Ventura River

- Manuel Canyon

- Cañada Larga

- Cañada de Alisos

- Coyote Creek

- Lake Casitas

- Laguna Creek

- Willow Creek

- Santa Ana Creek

- Roble-Casitas Canal

- Poplin Creek

- Deep Cat Lake

- East Fork Coyote Creek

- West Fork Coyote Creek

- Lake Casitas

- Matilija Creek

- Rattlesnake Creek

- Lime Creek

- Murietta Creek

- Middle Fork Matilija Creek

- Upper North Fork Matilija Creek

- North Fork Matilija Creek (This and Matilija Creek form the Ventura River's headwaters.)

- Santa Clara River

- Calleguas Creek

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 5,073 | — | |

| 1890 | 10,071 | 98.5% | |

| 1900 | 14,367 | 42.7% | |

| 1910 | 18,347 | 27.7% | |

| 1920 | 28,724 | 56.6% | |

| 1930 | 54,976 | 91.4% | |

| 1940 | 69,685 | 26.8% | |

| 1950 | 114,647 | 64.5% | |

| 1960 | 199,138 | 73.7% | |

| 1970 | 376,430 | 89.0% | |

| 1980 | 529,174 | 40.6% | |

| 1990 | 669,016 | 26.4% | |

| 2000 | 753,197 | 12.6% | |

| 2010 | 823,318 | 9.3% | |

| 2020 | 843,843 | 2.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[72] 1790-1960[73] 1900-1990[74] 1990-2000[75] 2010[76] 2020[77] | |||

2020 census

| Race / Ethnicity | Pop 2010[76] | Pop 2020[77] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 400,868 | 360,850 | 48.69% | 42.76% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 13,082 | 13,704 | 1.59% | 1.62% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 2,389 | 2,020 | 0.29% | 0.24% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 54,099 | 63,252 | 6.57% | 7.50% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 1,353 | 1,415 | 0.16% | 0.17% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 1,371 | 4,451 | 0.17% | 0.53% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (NH) | 18,589 | 32,866 | 2.26% | 3.89% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 331,567 | 365,285 | 40.27% | 43.29% |

| Total | 823,318 | 843,843 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Note: the US Census treats Hispanic/Latino as an ethnic category. This table excludes Latinos from the racial categories and assigns them to a separate category. Hispanics/Latinos can be of any race.

2011

| Population, race, and income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population[78] | 815,745 | ||||

| White[78] | 578,324 | 70.9% | |||

| Black or African American[78] | 14,435 | 1.8% | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native[78] | 9,186 | 1.1% | |||

| Asian[78] | 56,230 | 6.9% | |||

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander[78] | 1,410 | 0.2% | |||

| Some other race[78] | 123,892 | 15.2% | |||

| Two or more races[78] | 32,268 | 4.0% | |||

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race)[79] | 323,735 | 39.7% | |||

| Per capita income[80] | $32,740 | ||||

| Median household income[81] | $76,728 | ||||

| Median family income[82] | $86,321 | ||||

Places by population, race, and income

| Places by population and race | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place | Type[83] | Population[78] | White[78] | Other[78] [note 1] |

Asian[78] | Black or African American[78] |

Native American[78] [note 2] |

Hispanic or Latino (of any race)[79] |

| Bell Canyon | CDP | 2,291 | 83.9% | 3.0% | 10.3% | 0.0% | 2.7% | 3.4% |

| Camarillo | City | 64,340 | 73.0% | 13.8% | 10.7% | 1.4% | 1.0% | 24.5% |

| Casa Conejo | CDP | 3,424 | 89.0% | 4.6% | 2.1% | 4.3% | 0.0% | 32.6% |

| Channel Islands Beach | CDP | 3,299 | 94.0% | 4.8% | 1.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 19.2% |

| El Rio | CDP | 6,014 | 60.2% | 35.9% | 1.6% | 1.5% | 0.9% | 79.5% |

| Fillmore | City | 14,863 | 60.4% | 35.0% | 3.2% | 0.6% | 0.9% | 74.8% |

| Lake Sherwood | CDP | 1,396 | 88.4% | 6.0% | 0.5% | 2.5% | 2.6% | 2.9% |

| Meiners Oaks | CDP | 3,339 | 79.5% | 15.4% | 0.8% | 1.1% | 3.2% | 29.3% |

| Mira Monte | CDP | 7,666 | 86.7% | 9.2% | 1.8% | 0.9% | 1.4% | 15.7% |

| Moorpark | City | 34,100 | 75.1% | 18.3% | 5.4% | 1.0% | 0.2% | 31.2% |

| Oak Park | CDP | 14,045 | 85.4% | 4.3% | 9.6% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 6.2% |

| Oak View | CDP | 4,166 | 81.0% | 17.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.7% | 27.8% |

| Ojai | City | 7,496 | 84.4% | 13.4% | 2.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 17.0% |

| Oxnard | City | 194,972 | 59.7% | 26.6% | 7.9% | 3.2% | 2.6% | 71.6% |

| Piru | CDP | 1,638 | 60.0% | 39.9% | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 83.6% |

| Port Hueneme | City | 21,717 | 63.6% | 19.5% | 7.1% | 5.1% | 4.7% | 51.3% |

| San Buenaventura (Ventura) | City | 105,809 | 73.4% | 21.0% | 3.2% | 1.4% | 1.0% | 32.8% |

| Santa Paula | City | 29,248 | 53.0% | 45.5% | 0.6% | 0.2% | 0.7% | 78.8% |

| Santa Rosa Valley | CDP | 3,143 | 91.8% | 3.3% | 4.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6.5% |

| Santa Susana | CDP | 1,115 | 92.4% | 4.8% | 0.0% | 2.8% | 0.0% | 8.1% |

| Saticoy | CDP | 851 | 59.3% | 36.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4.3% | 74.7% |

| Simi Valley | City | 122,864 | 74.8% | 14.3% | 8.8% | 1.2% | 0.9% | 24.3% |

| Thousand Oaks | City | 125,633 | 79.6% | 9.1% | 9.8% | 1.1% | 0.4% | 16.0% |

| Places by population and income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place | Type[83] | Population[84] | Per capita income[80] | Median household income[81] | Median family income[82] |

| Bell Canyon | CDP | 2,291 | $85,789 | $220,764 | $230,455 |

| Camarillo | City | 64,340 | $37,840 | $84,168 | $101,334 |

| Casa Conejo | CDP | 3,424 | $26,950 | $84,286 | $86,630 |

| Channel Islands Beach | CDP | 3,299 | $53,891 | $70,313 | $69,333 |

| El Rio | CDP | 6,014 | $15,861 | $56,415 | $58,665 |

| Fillmore | City | 14,863 | $20,582 | $60,605 | $67,784 |

| Lake Sherwood | CDP | 1,396 | $104,724 | $210,391 | $211,484 |

| Meiners Oaks | CDP | 3,339 | $33,264 | $51,955 | $73,365 |

| Mira Monte | CDP | 7,666 | $32,718 | $71,723 | $83,968 |

| Moorpark | City | 34,100 | $36,375 | $103,009 | $107,412 |

| Oak Park | CDP | 14,045 | $55,681 | $128,618 | $143,188 |

| Oak View | CDP | 4,166 | $38,062 | $80,614 | $81,750 |

| Ojai | City | 7,496 | $36,769 | $63,750 | $89,338 |

| Oxnard | City | 194,972 | $20,612 | $60,191 | $61,965 |

| Piru | CDP | 1,638 | $15,730 | $49,141 | $47,734 |

| Port Hueneme | City | 21,717 | $23,391 | $52,244 | $56,566 |

| San Buenaventura (Ventura) | City | 105,809 | $31,775 | $66,226 | $81,616 |

| Santa Paula | City | 29,248 | $19,713 | $53,359 | $55,399 |

| Santa Rosa Valley | CDP | 3,143 | $71,594 | $154,931 | $176,938 |

| Santa Susana | CDP | 1,115 | $40,271 | $111,610 | $112,027 |

| Saticoy | CDP | 851 | $12,192 | $34,375 | $35,299 |

| Simi Valley | City | 122,864 | $35,467 | $89,452 | $97,999 |

| Thousand Oaks | City | 125,633 | $46,093 | $100,373 | $112,876 |

2010

The 2010 United States Census reported that Ventura County had a population of 823,318. The racial makeup of Ventura County was 565,804 (68.7%) White, 15,163 (1.8%) African American, 8,068 (1.0%) Native American, 55,446 (6.7%) Asian, 1,643 (0.2%) Pacific Islander, 140,253 (17.0%) from other races, and 36,941 (4.5%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 331,567 persons (40.3%).[85]

| Population reported at 2010 United States Census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The County | Total Population | White | African American | Native American | Asian | Pacific Islander | other races | two or more races | Hispanic or Latino (of any race) |

| Ventura County | 823,318 | 565,804 | 15,163 | 8,068 | 55,446 | 1,643 | 140,253 | 36,941 | 331,567 |

| Incorporated cities and towns | Total Population | White | African American | Native American | Asian | Pacific Islander | other races | two or more races | Hispanic or Latino (of any race) |

| Camarillo | 65,201 | 48,947 | 1,216 | 397 | 6,633 | 116 | 4,774 | 3,118 | 14,958 |

| Fillmore | 15,002 | 8,581 | 75 | 180 | 155 | 12 | 5,204 | 795 | 11,212 |

| Moorpark | 34,421 | 25,860 | 533 | 248 | 2,352 | 50 | 3,727 | 1,651 | 10,813 |

| Ojai | 7,461 | 6,555 | 42 | 47 | 158 | 1 | 440 | 218 | 1,339 |

| Oxnard | 197,899 | 95,346 | 5,771 | 2,953 | 14,550 | 658 | 69,527 | 9,094 | 145,551 |

| Port Hueneme | 21,723 | 12,357 | 1,111 | 295 | 1,299 | 119 | 5,224 | 1,318 | 11,360 |

| Santa Paula | 29,321 | 18,458 | 152 | 460 | 216 | 24 | 8,924 | 1,087 | 23,299 |

| Simi Valley | 124,237 | 93,597 | 1,739 | 761 | 11,555 | 178 | 10,685 | 5,722 | 28,938 |

| Thousand Oaks | 126,683 | 101,702 | 1,674 | 497 | 11,043 | 146 | 6,869 | 4,752 | 21,341 |

| Ventura | 106,433 | 81,553 | 1,724 | 1,287 | 3,663 | 206 | 12,486 | 5,514 | 33,874 |

| Census-designated places | Total Population | White | African American | Native American | Asian | Pacific Islander | other races | two or more races | Hispanic or Latino (of any race) |

| Bell Canyon | 2,049 | 1,724 | 58 | 4 | 179 | 0 | 10 | 74 | 103 |

| Casa Conejo | 3,249 | 2,560 | 27 | 20 | 160 | 4 | 327 | 151 | 851 |

| Channel Islands Beach | 3,103 | 2,712 | 27 | 16 | 108 | 6 | 103 | 131 | 402 |

| El Rio | 7,198 | 3,495 | 58 | 201 | 73 | 24 | 3,027 | 320 | 6,188 |

| Lake Sherwood | 1,527 | 1,368 | 5 | 1 | 101 | 0 | 9 | 43 | 52 |

| Meiners Oaks | 3,571 | 2,789 | 14 | 58 | 51 | 1 | 549 | 109 | 1,068 |

| Mira Monte | 6,854 | 5,989 | 43 | 61 | 129 | 3 | 406 | 223 | 1,254 |

| Oak Park | 13,811 | 11,473 | 141 | 32 | 1,556 | 9 | 162 | 438 | 826 |

| Oak View | 4,066 | 3,227 | 11 | 63 | 34 | 3 | 575 | 153 | 1,217 |

| Piru | 2,063 | 1,063 | 16 | 43 | 11 | 0 | 830 | 100 | 1,748 |

| Santa Rosa Valley | 3,334 | 2,904 | 23 | 13 | 187 | 4 | 102 | 101 | 353 |

| Santa Susana | 1,037 | 904 | 17 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 33 | 58 | 156 |

| Saticoy | 1,029 | 413 | 9 | 29 | 2 | 0 | 508 | 68 | 895 |

| Other unincorporated areas | Total Population | White | African American | Native American | Asian | Pacific Islander | other races | two or more races | Hispanic or Latino (of any race) |

| All others not CDPs (combined) | 42,046 | 32,227 | 677 | 400 | 1,208 | 79 | 5,752 | 1,703 | 13,769 |

2000

As of the census[86] of 2000, there were 753,197 people, 243,234 households, and 182,911 families living in the county. The population density was 408 inhabitants per square mile (158/km2). There were 251,712 housing units at an average density of 136 per square mile (53/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 69.9% White, 5.4% Asian, 2.0% Black or African American, 0.9% Native American, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 17.7% from other races, and 3.9% from two or more races. About one third (33.4%) of the population is Hispanic or Latino of any race. 9.8% were of German, 7.7% English and 7.1% Irish ancestry according to Census 2000. 67.1% spoke English, 26.2% Spanish and 1.5% Tagalog as their first language.

There were 243,234 households, of which 39.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 59.5% were married couples living together, 10.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 24.8% were non-families. 18.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.04 and the average family size was 3.46.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 28.4% under the age of 18, 9.0% from 18 to 24, 30.7% from 25 to 44, 21.7% from 45 to 64, and 10.2% who were 65 or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.5 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $59,666, and the median income for a family was $65,285. Males had a median income of $45,310, versus $32,216 for females. The per capita income for the county was $24,600. About 6.4% of families and 9.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 11.6% of those under age 18 and 6.3% of those aged 65 or over.

According to an updated 2005 US Census, median household income was $66,859, while the mean was $85,032. Per capita income was up to $29,634, making it the 6th wealthiest county in California.

Housing

Ventura County typically has limited housing inventory, making it a consistently expensive location in Southern California, where it is usually the third-most-expensive county behind Orange and Los Angeles counties.[87] As of March 2018, the county was not on track to meet its state-mandated housing goals. Individual cities are responsible for meeting their assigned housing goals, while the county government is responsible for housing goals in unincorporated areas.[88][89] Several affordable housing groups that are actively working on building housing for veterans and low income people have long waiting lists.[90][91] Farmworker housing also has waiting lists though designated units continue to be built.[92]

Metropolitan Statistical Area

The United States Office of Management and Budget has designated Ventura County as the Oxnard–Thousand Oaks–Ventura, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area.[93] The United States Census Bureau ranked the Oxnard–Thousand Oaks–Ventura, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area as the 66th most populous metropolitan statistical area of the United States as of July 1, 2012.[94]

The Office of Management and Budget has further designated the Oxnard–Thousand Oaks–Ventura, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area as a component of the more extensive Los Angeles–Long Beach, CA Combined Statistical Area,[93] the second most populous combined statistical area and primary statistical area of the United States as of July 1, 2012.[94][95]

Economy

In 2019, the county faced a weak economic outlook due to the declining housing affordability and lack of job growth.[96][97][98][99]

Agriculture

Lemons are the number two crop in the county according to the 2018 crop and livestock report. The economic value of lemons is more than $244 million a year, Valencia oranges are nearly $20 million a year, and mandarins/tangelos are more than $17 million a year.[100][101]

The county became a major producer in the state for hemp after it was removed from a list of controlled substances along with other provisions of the Hemp Farming Act of 2018. These provisions were included in the 2018 Farm Bill which made hemp legal for agricultural uses.[102] The agricultural commissioner enforces state rules regarding testing of the plants, varieties that can be grown and registration of acreage. By October 2019, close to 4,100 acres (1,700 ha) for cultivation and seed breeding have been registered in the county.[103] The annual crop report had 3,470 harvestable acres for 2019 with an estimated gross value $35.5 million.[104]

Several cities within the county are banning or have a moratorium on the planting, harvesting, drying, processing and manufacture of hemp products.[105] These city councils were reacting to complaints about the smell.[106] With some fields in unincorporated area being near residences, homeowners also brought their concerns to the county board of supervisors.[107] The acreage available for planting was reduced when a buffer zone was established around schools and residential communities in 2020.[108]

Cannabis

State law says local governments may not prohibit adults from growing, using or transporting marijuana for personal use but they can prohibit companies from growing, testing, and selling cannabis within their jurisdiction by licensing none or only some of these activities. The state allows deliveries without local agency licensing at the point of delivery.[109]

Under the legalization of the sale and distribution of cannabis in California, Ventura County voters approved Measure O in 2020, which sets up taxes on marijuana cultivation, as well as limits on the amounts of growing.[110] Allowing retail sales to the general public in the unincorporated areas was not approved as part of the referendum although sales are allowed within the cities of Port Hueneme and Ojai.[111] It restricted operations to the inside of existing greenhouses with only 500 acres (200 ha) of commercial cannabis allowed within the county, though an additional 100 acres (40 ha) is available for nursery cultivation.[112]

A 5.5-million-square-foot (0.51-million-square-metre) greenhouse facility, on which construction had begun in 1996 to grow tomatoes and other produce, began preparing to grow cannabis in 2021 under the rules put in place by Measure O.[112][113][114][115]

Technology

Amgen, the Thousand Oaks-based biotechnology giant, is the biggest publicly-traded company in Ventura County by market capitalization. The Trade Desk, the Ventura-based industry leader in advertising on streaming services, is second.[116]

Sports

The city of Ventura is home to the soccer club, Ventura County Fusion, of the USL Premier Development League.

Government

Current county supervisors are Matt LaVere (District 1), Jeff Gorell (District 2), Kelly Long (District 3), Janice Parvin (District 4), and Vianey Lopez (District 5).[117] Dr. Sevet Johnson is the Interim County Executive Officer.[118] James Fryhoff is the sheriff of the Ventura County Sheriff's Department.[119] Dustin Gardner is the chief of the Ventura County Fire Department.[120]

Federal and state representation

Much of the county, including the cities of Thousand Oaks, Oxnard and Moorpark, lie within the 26th congressional district, which is represented by Democrat Julia Brownley.[121] Other parts of the county are in California's 24th congressional district, represented by Democrat Salud Carbajal, California's 25th congressional district, represented by Democrat Raul Ruiz, and California's 30th congressional district, represented by Democrat Adam Schiff.[122] For the previous twenty five years, most of Ventura County was represented by Elton Gallegly, a conservative Republican from Simi Valley, who retired in 2012.

In the California State Senate, Ventura County is split between the 19th Senate District, represented by Democrat Monique Limón, and the 27th Senate District, represented by Democrat Henry Stern.[123]

In the California State Assembly, Ventura County is split between four legislative districts:[124]

- the 37th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Gregg Hart,

- the 38th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Steve Bennett,

- the 44th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Laura Friedman, and

- the 45th Assembly District, represented by Democrat James Ramos

County supervisors

Ventura County is administered by five elected Supervisors who each serve four year terms. They appoint department administrators who manage county functions. The county seal, that was adopted in 1964, was reviewed in 2022 due to prominent depiction of Junípero Serra that could be hurtful to those who allege that Serra was responsible for the suppression of the culture of Chumash people.[125] The seal also had images referring to atomic energy and oil drilling that no longer represented the county industries.[126] A new seal was adopted that depicts Arch Rock off Anacapa Island.[127]

Ventura County Sheriff

The Ventura County Sheriff provides court protection, county jail administration, and patrol for the unincorporated areas of the county plus contracted police services for the incorporated cities of Thousand Oaks, Fillmore, Camarillo, Moorpark, and Ojai.

Municipal police departments

The incorporated cities of Ventura, Oxnard, Simi Valley, Port Hueneme, and Santa Paula have municipal police departments.

2040 General Plan

In 2020, the County of Ventura updated its general plan to the Ventura County 2040 General Plan, as mandated by the California Office of Planning and Research.[128] This document establishes guidelines and a regulatory basis for development and policy-making in the county until it is updated again in 2040.[129] The County held surveys, workshops, advisory committees, and hearings to encourage community participation in the process of shaping and adopting the Ventura County 2040 General Plan.[130] The final 2040 General Plan, adopted on September 15, 2020, by the Ventura County Board of Supervisors, is centered on the following nine elements of governance:

- Land Use and Community Character

- Housing

- Circulation, Transportation, and Mobility

- Public Facilities, Services, and Infrastructure

- Conservation and Open Space

- Hazards and Safety

- Agriculture

- Water Resources

- Economic Vitality.[131]

The Environmental Impact Review done by the state on the Ventura County 2040 General Plan Update, as required by the California Environmental Quality Act, projects that the county will see a population increase of 13% from 2018 to 2040.[132] As such, the review found no significant population or housing need changes anticipated for the county during this period.[132]

A 2020 lawsuit filed against the county by The Ventura County Coalition of Labor, Agriculture and Business and the Ventura County Agricultural Association opposed policies in the 2040 General Plan which restricted oil and gas development, raised costs of agriculture, set high housing quality standards, and limited brush clearance.[133] The suit was settled in February 2023 with the county's adoption of an Implementation Clarification for Certain Policies and Programs Contained in the 2040 General Plan, which stated the county's ongoing support of agricultural operations without altering the content of the Plan.[134]

Politics

For many years, Ventura County voted consistently for Republican candidates for local, statewide and federal offices. Only recently has the county begun favoring Democratic candidates in both federal and state elections. While Republicans used to win a large majority of votes throughout the 1970s and 1980s, no party received greater than 55% of the county's vote from 1992 to 2016. Prior to Barack Obama's victory in the county in 2008, the last Democrat to win a majority was Lyndon Johnson in 1964, though Democrat Bill Clinton carried the county by a plurality in 1992 and 1996.

On March 3, 2008, Democratic registration surpassed Republican registration and the former's edge has grown since.[135] The cities of Camarillo, Moorpark, Simi Valley, and Thousand Oaks all have voter rolls with Republican pluralities. The remaining cities and towns in the county have a Democratic plurality or majority on the voter rolls, while the unincorporated areas are split almost evenly between the parties.[136]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 162,207 | 38.36% | 251,388 | 59.45% | 9,230 | 2.18% |

| 2016 | 132,323 | 37.16% | 194,402 | 54.59% | 29,382 | 8.25% |

| 2012 | 147,958 | 45.15% | 170,929 | 52.16% | 8,825 | 2.69% |

| 2008 | 145,853 | 42.77% | 187,601 | 55.01% | 7,587 | 2.22% |

| 2004 | 160,314 | 51.19% | 148,859 | 47.53% | 4,020 | 1.28% |

| 2000 | 136,173 | 48.17% | 133,258 | 47.14% | 13,261 | 4.69% |

| 1996 | 109,202 | 43.47% | 110,772 | 44.10% | 31,220 | 12.43% |

| 1992 | 94,911 | 35.46% | 99,011 | 36.99% | 73,725 | 27.55% |

| 1988 | 147,604 | 61.64% | 89,065 | 37.19% | 2,804 | 1.17% |

| 1984 | 151,383 | 68.67% | 66,550 | 30.19% | 2,529 | 1.15% |

| 1980 | 114,930 | 60.28% | 56,311 | 29.54% | 19,409 | 10.18% |

| 1976 | 82,670 | 53.20% | 68,529 | 44.10% | 4,201 | 2.70% |

| 1972 | 95,310 | 63.20% | 49,307 | 32.70% | 6,188 | 4.10% |

| 1968 | 59,705 | 51.35% | 47,794 | 41.11% | 8,762 | 7.54% |

| 1964 | 40,264 | 40.99% | 57,805 | 58.84% | 169 | 0.17% |

| 1960 | 35,074 | 49.59% | 35,334 | 49.96% | 315 | 0.45% |

| 1956 | 26,342 | 49.92% | 26,276 | 49.80% | 149 | 0.28% |

| 1952 | 24,534 | 52.47% | 21,967 | 46.98% | 256 | 0.55% |

| 1948 | 13,930 | 42.15% | 18,100 | 54.77% | 1,019 | 3.08% |

| 1944 | 11,071 | 40.19% | 16,342 | 59.33% | 131 | 0.48% |

| 1940 | 11,225 | 42.15% | 15,182 | 57.00% | 227 | 0.85% |

| 1936 | 7,579 | 35.75% | 13,384 | 63.14% | 235 | 1.11% |

| 1932 | 6,908 | 37.27% | 10,903 | 58.82% | 724 | 3.91% |

| 1928 | 9,017 | 70.17% | 3,717 | 28.92% | 117 | 0.91% |

| 1924 | 5,705 | 65.16% | 911 | 10.41% | 2,139 | 24.43% |

| 1920 | 5,231 | 76.00% | 1,305 | 18.96% | 347 | 5.04% |

| 1916 | 3,980 | 55.18% | 2,835 | 39.30% | 398 | 5.52% |

| 1912 | 71 | 1.47% | 2,108 | 43.62% | 2,654 | 54.91% |

| 1908 | 1,864 | 56.57% | 1,181 | 35.84% | 250 | 7.59% |

| 1904 | 1,995 | 63.86% | 840 | 26.89% | 289 | 9.25% |

| 1900 | 1,708 | 53.54% | 1,333 | 41.79% | 149 | 4.67% |

| 1896 | 1,553 | 50.41% | 1,465 | 47.55% | 63 | 2.04% |

| 1892 | 1,283 | 46.60% | 958 | 34.80% | 512 | 18.60% |

| 1888 | 1,107 | 53.84% | 906 | 44.07% | 43 | 2.09% |

| 1884 | 749 | 53.96% | 603 | 43.44% | 36 | 2.59% |

| 1880 | 599 | 53.24% | 522 | 46.40% | 4 | 0.36% |

| Year | GOP | DEM |

|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 45.5% 127,709 | 54.5% 153,226 |

| 2018 | 44.4% 137,393 | 55.6% 171,729 |

| 2014 | 46.9% 93,797 | 53.1% 106,072 |

| 2010 | 49.3% 128,082 | 45.3% 117,800 |

| 2006 | 61.0% 134,862 | 34.3% 75,790 |

| 2003 | 51.5% 116,722 | 23.7% 53,705 |

| 2002 | 47.2% 91,193 | 43.2% 83,557 |

| 1998 | 43.8% 91,093 | 53.0% 110,226 |

| 1994 | 62.4% 136,417 | 33.4% 73,163 |

| 1990 | 57.6% 106,234 | 36.9% 68,139 |

| 1986 | 67.2% 118,640 | 31.1% 54,893 |

| 1982 | 55.2% 99,130 | 42.4% 76,094 |

| 1978 | 40.6% 57,777 | 52.8% 75,173 |

| 1974 | 50.5% 60,122 | 47.2% 56,189 |

| 1970 | 58.6% 63,790 | 38.9% 42,350 |

| 1966 | 60.9% 58,068 | 39.1% 37,224 |

| 1962 | 45.2% 31,899 | 53.5% 37,777 |

Voter registration statistics

| Population and registered voters | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total population[78] | 815,745 | |

| Registered voters[138][note 3] | 431,154 | 52.9% |

| Democratic[138] | 166,462 | 38.6% |

| Republican[138] | 155,180 | 36.0% |

| Democratic–Republican spread[138] | +11,282 | +2.6% |

| American Independent[138] | 11,072 | 2.6% |

| Green[138] | 2,324 | 0.5% |

| Libertarian[138] | 2,700 | 0.6% |

| Peace and Freedom[138] | 926 | 0.2% |

| Americans Elect[138] | 13 | 0.0% |

| Other[138] | 5,733 | 1.3% |

| No party preference[138] | 86,744 | 20.1% |

Cities by population and voter registration

| Cities by population and voter registration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Population[78] | Registered voters[138] [note 3] |

Democratic[138] | Republican[138] | D–R spread[138] | Other[138] | No party preference[138] |

| Camarillo | 64,340 | 63.2% | 33.1% | 43.2% | -10.1% | 7.8% | 18.6% |

| Fillmore | 14,863 | 42.7% | 47.0% | 27.8% | +19.2% | 7.7% | 20.0% |

| Moorpark | 34,100 | 58.6% | 33.8% | 40.8% | -7.0% | 7.8% | 20.2% |

| Ojai | 7,496 | 65.9% | 46.0% | 27.3% | +18.7% | 9.1% | 20.2% |

| Oxnard | 194,972 | 36.4% | 51.6% | 22.5% | +29.1% | 6.4% | 21.5% |

| Port Hueneme | 21,717 | 40.4% | 47.5% | 25.2% | +22.3% | 8.1% | 21.8% |

| San Buenaventura (Ventura) | 105,809 | 61.1% | 42.4% | 32.3% | +10.1% | 8.5% | 19.4% |

| Santa Paula | 29,248 | 39.8% | 53.4% | 23.7% | +29.7% | 6.6% | 18.5% |

| Simi Valley | 122,864 | 57.8% | 30.3% | 44.7% | -14.4% | 8.2% | 19.6% |

| Thousand Oaks | 125,633 | 62.4% | 31.9% | 41.8% | -9.9% | 8.0% | 21.0% |

Crime

Ventura County is home to several of the safest communities in the U.S., including Thousand Oaks, Simi Valley, Newbury Park, and Moorpark. Overall, crime in the county is 33% lower than California and U.S. rates.[139]

According to a 2019 report, the county is the second safest county among California's most populated counties.[140]

The following table includes the number of incidents reported and the rate per 1,000 persons for each type of offense.

| Population and crime rates | ||

|---|---|---|

| Population[78] | 815,745 | |

| Violent crime[141] | 2,021 | 2.48 |

| Homicide[141] | 29 | 0.04 |

| Forcible rape[141] | 116 | 0.14 |

| Robbery[141] | 757 | 0.93 |

| Aggravated assault[141] | 1,119 | 1.37 |

| Property crime[141] | 7,696 | 9.43 |

| Burglary[141] | 2,954 | 3.62 |

| Larceny-theft[141][note 4] | 11,221 | 13.76 |

| Motor vehicle theft[141] | 1,154 | 1.41 |

| Arson[141] | 113 | 0.14 |

Cities by population and crime rates

| Cities by population and crime rates | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Population[142] | Violent crimes[142] | Violent crime rate per 1,000 persons |

Property crimes[142] | Property crime rate per 1,000 persons | |||

| Camarillo | 66,506 | 61 | 0.92 | 955 | 14.36 | |||

| Fillmore | 15,298 | 24 | 1.57 | 198 | 12.94 | |||

| Moorpark | 35,102 | 41 | 1.17 | 330 | 9.40 | |||

| Ojai | 7,607 | 13 | 1.71 | 162 | 21.30 | |||

| Oxnard | 201,797 | 603 | 2.99 | 4,071 | 20.17 | |||

| Port Hueneme | 22,142 | 65 | 2.94 | 467 | 21.09 | |||

| Santa Paula | 29,899 | 91 | 3.04 | 590 | 19.73 | |||

| Simi Valley | 126,686 | 141 | 1.11 | 1,916 | 15.12 | |||

| Thousand Oaks | 129,171 | 157 | 1.22 | 1,838 | 14.23 | |||

| Ventura | 108,511 | 310 | 2.86 | 3,885 | 35.80 | |||

Transportation

Major highways

Unconstructed

Public transportation

Ventura County is served by Amtrak and Metrolink trains along the main coast rail line, as well as Greyhound Lines, Gold Coast Transit (formerly South Coast Area Transit), and VISTA buses. The cities of Camarillo, Moorpark, Simi Valley and Thousand Oaks have their own small bus systems.

Park authorized commercial service operators provide access to the five islands of Channel Islands National Park.[143]

Airports

- Oxnard Airport, just west of Downtown Oxnard and was Ventura County's only commercial airport, it now no longer takes public flights. It is also the county's largest airport.

- Camarillo Airport, formerly a US Air Force Base, is a general aviation airport located south of the City of Camarillo. It is the current base of operations of the Ventura County Sheriff's Department Aviation Unit and the home of the VCSD's Training Facility and Academy, the Ventura County Criminal Justice Training Center. The Camarillo Airport also serves as the base of operations for the Ventura County Fire Department and facilitates the Oxnard College Regional Fire Academy and the Ventura County Reserve Officers Training Center.

- Santa Paula Airport is a privately owned airport open to the public for general aviation.

Education

K-12 education

School districts include:[144]

Unified:

- Conejo Valley Unified School District

- Cuyama Joint Unified School District

- El Tejon Unified School District

- Fillmore Unified School District

- Las Virgenes Unified School District

- Moorpark Unified School District

- Oak Park Unified School District

- Ojai Unified School District

- Santa Paula Unified School District - Includes some areas for PK-12 and some for 9-12 only

- Simi Valley Unified School District

- Ventura Unified School District

Secondary:

Elementary:

- Briggs Elementary School District

- Hueneme Elementary School District

- Mesa Union Elementary School District

- Mupu Elementary School District

- Ocean View Elementary School District

- Oxnard Elementary School District

- Pleasant Valley Elementary School District

- Rio Elementary School District

- Santa Clara Elementary School District

- Somis Union Elementary School District

Public libraries

Ventura County Library has 12 community library locations throughout the county, including three branches in the city of Ventura. Many of the other branches serve smaller towns or unincorporated communities. The county library also includes the Research Library of the Museum of Ventura County. In addition, six cities within the county operate their own city libraries that are independent of the county system: Camarillo, Moorpark, Oxnard, Santa Paula, Simi Valley, and Thousand Oaks.

Academic libraries

The colleges and universities in Ventura County support libraries to meet the research needs of their students and faculty and, in some cases, the general public. These include:

- Edward Laurence Doheny Memorial Library and Carrie Estelle Doheny Memorial Library, St. John's Seminary (Camarillo)

- Evelyn and Howard Boroughs Library, Ventura College[145]

- John Spoor Broome Library, California State University Channel Islands (Camarillo)

- Moorpark College Library

- Oxnard College Library

- Pearson Library, California Lutheran University (Thousand Oaks)[146]

- St. Bernardine of Siena Library, Thomas Aquinas College (Santa Paula)[147]

Other libraries

The Ronald Reagan Presidential Library is located in Simi Valley.

Ventura County Law Library, located in the Ventura County Government Center, makes current legal resources available to judges, lawyers, government officials, and other users.

Communities

Cities

- Camarillo

- Fillmore

- Moorpark

- Ojai

- Oxnard

- Port Hueneme

- Santa Paula

- Simi Valley

- Thousand Oaks

- Ventura (county seat)

Unincorporated communities

- Bardsdale

- Bell Canyon[note 5]

- Buckhorn

- Casa Conejo[note 5]

- Casitas Springs

- Channel Islands Beach[note 5]

- Dulah

- El Rio[note 5]

- Faria

- La Conchita

- Lake Sherwood[note 5]

- Meiners Oaks[note 5]

- Mira Monte[note 5]

- Mussel Shoals

- Newbury Park

- Oak Park[note 5]

- Oak View[note 5]

- Ortonville

- Piru[note 5]

- Point Mugu

- Santa Rosa Valley[note 5]

- Santa Susana[note 5]

- Sea Cliff

- Silver Strand Beach

- Saticoy[note 5]

- Solromar

- Somis[note 5]

- Upper Ojai

- Wheeler Springs

Population ranking

The population ranking of the following table is based on the 2020 census of Ventura County.[148]

† county seat

| Rank | City/Town/etc. | Municipal type | Population (2020 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Oxnard | City | 202,736 |

| 2 | Thousand Oaks | City | 126,966 |

| 3 | Simi Valley | City | 126,356 |

| 4 | † Ventura (San Buenaventura) | City | 110,763 |

| 5 | Camarillo | City | 70,741 |

| 6 | Moorpark | City | 36,284 |

| 7 | Santa Paula | City | 30,657 |

| 8 | Port Hueneme | City | 21,954 |

| 9 | Fillmore | City | 16,419 |

| 10 | Oak Park | CDP | 13,898 |

| 11 | Ojai | City | 7,637 |

| 12 | El Rio | CDP | 7,037 |

| 13 | Mira Monte | CDP | 6,618 |

| 14 | Oak View | CDP | 6,215 |

| 15 | Meiners Oaks | CDP | 3,911 |

| 16 | Santa Rosa Valley | CDP | 3,312 |

| 17 | Casa Conejo | CDP | 3,267 |

| 18 | Channel Islands Beach | CDP | 2,870 |

| 19 | Piru | CDP | 2,587 |

| 20 | Bell Canyon | CDP | 1,946 |

| 21 | Lake Sherwood | CDP | 1,759 |

| 22 | Somis | CDP | 1,429 |

| 23 | Santa Susana | CDP | 1,160 |

| 24 | Saticoy | CDP | 1,133, |

In popular culture

Lake Sherwood is named for its use as the location for Sherwood Forest in the 1922 film, Robin Hood, starring Douglas Fairbanks.[149][150] The 1938 film, The Adventures of Robin Hood, starring Errol Flynn, also had a major scene shot on location at "Sherwood Forest".[151]

On July 23, 1982, actor Vic Morrow and two children actors (My-Ca Dinh Le and Renee Shin-Ye Chen) were filming a helicopter scene for Twilight Zone: The Movie in the area of Indian Dunes in Ventura County when the helicopter lost control and crashed on top of them. Morrow and Le were decapitated and Chen was fatally crushed.

In 1963, the Korean War story The Young and The Brave, featuring a brave and resourceful young boy, was filmed in rural areas of Ventura County.

Also, in 2000 the movie Swordfish filmed the final bank scene on East Main Street in Ventura. The building they used is the white building on the corner. 34.280823°N 119.294599°W

In 2009, the VH1 television show Tool Academy was filmed in Ventura County.

The movie Back to the Future Part III filmed the scene where Marty returns to the year 1985 in the time-traveling DeLorean at the railroad crossing at S Ventura Rd & Shoreview Dr in Port Hueneme.

Many films, including Little Miss Sunshine, Sideways, Chinatown, Erin Brockovich, The Aviator, and The Rock were partly filmed in Ventura.

Downtown Ventura hosts the Majestic Ventura Theater, an early 20th century theatre, which is situated about two blocks away from city hall. It is the region's most prominent local musical venue and hosts concerts regularly. The theater has hosted many internationally notable musician and bands such as Gregg Allman, John Prine, Glenn Frey, The Doors, Devo, Joe Walsh, King's X, Van Halen, X, Paramore, She Wants Revenge, Pennywise, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Snoop Dogg, Drakeo the Ruler, DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince, The Game, DJ Quik, Lamb of God, Social Distortion, Bad Religion, Thrice, Avenged Sevenfold, Fugazi, Incubus, Tom Petty, America, They Might Be Giants, and Modest Mouse, as well as local artists such as Army of Freshmen and Big Bad Voodoo Daddy.

See also

Notes

- Other = Some other race + Two or more races

- Native American = Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander + American Indian or Alaska Native

- Percentage of registered voters with respect to total population. Percentages of party members with respect to registered voters follow.

- Only larceny-theft cases involving property over $400 in value are reported as property crimes.

- For statistical purposes, defined by the United States Census Bureau as a census-designated place (CDP).

References

- "Ventura County". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- "About Us - Ventura County". Ventura.org. Ventura County Executive Office. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- "Matt LaVere, Supervisor, District 1 from Ventura County, California".

- "Linda Parks, Supervisor, District 2 from Ventura County, California".

- "Kelly Long, Supervisor, District 3 from Ventura County, California".

- "Bob Huber, Supervisor, District 4 from Ventura County, California".

- "Carmen Ramirez, Supervisor, District 5 from Ventura County, California".

- "Board of Supervisors".

- "Mount Pinos". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- "Ventura County, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Central Coast". California State Parks. California Department of Recreation. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- "Anacapa Island History and Culture - Channel Islands National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- Johnson, John R. 1997. Chumash Indians in Simi Valley: A Journey Through Time. Simi Valley, CA: Simi Valley Historical Society. ISBN 978-0965944212. Page 6.

- Starr, Kevin. 2007. California: A History. Modern Library Chronicles 23. New York City, NY: Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8129-7753-0. Page 13.

- Lynne McCall & Perry Rosalind (ed.). 1991. The Chumash People: Materials for Teachers and Students. Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. San Luis Obispo, CA: EZ Nature Books. ISBN 0-945092-23-7. Page 31.

- California Coastal Commission (1987). California Coastal Resource Guide. University of California Press. p. 267. ISBN 0520061853.

- "Point Hueneme". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- Hindawi. "Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine — An Open Access Journal". www.hindawi.com. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- Davidson, Keay (June 20, 2005). "Did ancient Polynesians visit California? Maybe so. / Scholars revive idea using linguistic ties, Indian headdress". SF Gate. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- "Ventureño – Survey of California and Other Indian Languages". linguistics.berkeley.edu. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- Harrington, John Peabody. The Papers of John Peabody Harrington in the Smithsonian Institution 1907-1957. Kraus International Publications, 1981, 3.89.66-73.

- Johnson, John R. 1997. Chumash Indians in Simi Valley: A Journey Through Time. Simi Valley, CA: Simi Valley Historical Society. ISBN 978-0965944212. Page 8.

- Lynne McCall & Perry Rosalind (ed.). 1991. The Chumash People: Materials for Teachers and Students. Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. San Luis Obispo, CA: EZ Nature Books. ISBN 0-945092-23-7. Pages 29-30.

- Arnold L. Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California. Oxnard, CA: M & N, 1979; pp. 3–4.

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, p. 6.

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, p. 8.

- Erwin G. Gudde, California Place Names: The Origin and Etymology of Current Geographical Names, 4th ed., rev. and enlarged by William Bright (University of California Press, 1998), p. 410.

- Griggs, Gary B. and Kiki Patsch (2005). Living with the Changing California Coast. University of California Press. Page 399. ISBN 9780520244474.

- Johnson, John R. (1982). "The Trail to Fernando". Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 4: 132–37.

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, p. 11.

- "Ventura County Spanish and Mexican Land Grants". Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, p. 12.

- Clerici, Kevin (July 17, 2007). "Artifacts are found at site". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, pp. 12–13.

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, p. 15.

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, pp. 16–17.

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, pp. 22–23.

- "El Rio, California", Wikipedia, July 10, 2023, retrieved October 25, 2023

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, pp. 23–24.

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, pp. 25–27.

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, p. 27.

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, p. 25.

- Vincent, Ann. "Chatsworth past & present" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- "History of Oxnard & The Oxnard Police Department". Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- "About Oxnard California - City of Oxnard Information - Visit Oxnard". Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, pp. 27–29.

- California Oil and Gas Fields, Volumes I, II and III. Vol. I (1998), Vol. II (1992), Vol. III (1982). California Department of Conservation, Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR), p. 573.

- Pollack, Alan (March–April 2010). "President's Message" (PDF). The Heritage Junction Dispatch. Santa Clara Valley Historical Society.

- Murphy, A Comprehensive Story of Ventura County, California, p. 31.

- Brant, Cherie (2006). Keys to the County: Touring Historic Ventura County. Ventura County Museum. Page 133. ISBN 978-0972936149.

- "Comprehensive Review of Water Service/Outside Area Update" (PDF). Administrative Report:City Council Action Date January 23, 2012. City of Ventura. January 5, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 3, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- Michael Livingston; Javier Panzar (December 23, 2017). "Thomas fire becomes largest wildfire on record in California". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 23, 2017.

- "Deadly Thomas Fire in Ventura County explodes to 31,000 acres overnight, 150 structures burned". Fox5News. December 5, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- Annette Ding (April 10, 2018). "Charting the Financial Damage of the Thomas Fire". The Bottom Line. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- Tyler Hersko (January 23, 2018). "Ventura County agriculture suffers over $170 million in damages from Thomas Fire". Ventura County Star. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- Chelsea Edwards (December 11, 2017). "Thomas Fire grows to 230,000 acres as it continues destructive path into Santa Barbara County". ABC 7. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- Hersko, Tyler (January 3, 2018). "Burned by Thomas Fire, Ventura County farmers look toward recovery". Ventura County Star. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Kisken, Tom (November 27, 2019). "Valley fever rate stays high in Ventura County, sparks debate about fire, global warming". Ventura County Star. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- Wilson, Kathleen (December 28, 2019). "The money is in: County gets more than $16M from Edison". Ventura County Star. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "Pace of urbanization slows in Los Angeles, Ventura counties, new doc maps show". Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- Erwin G. Gudde, William Bright (2004). California Place Names: The Origin and Etymology of Current Geographical Names.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (C. Robert Elford). 1970. Soil Survey: Ventura Area, California. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. Page 142.

- Fernandez, Lisa (August 2, 1997). "Storyteller Keeps Chumash Ways Alive in Word, Deed". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- Ingraham, Christopher (August 17, 2015). "Every county in America, ranked by scenery and climate". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- Wilson, Kathleen (March 11, 2019). "Wildlife passage proposal goes to Ventura County Board of Supervisors on Tuesday". Ventura County Star. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (C. Robert Elford). 1970. Soil Survey: Ventura Area, California. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. Pages 142-143.

- Ginsberg, Joanne S. (1991). California Coastal Access Guide. University of California Press. Page 185. ISBN 9780520050518.

- Wilson, Kathleen (September 28, 2019). "Ventura County wrongly criticized in EPA air warning, local official says". Ventura County Star. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- "Census of Population and Housing from 1790-2000". US Census Bureau. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Ventura County, California". United States Census Bureau.

- "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Ventura County, California". United States Census Bureau.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B02001. U.S. Census website. Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B03003. U.S. Census website. Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19301. U.S. Census website. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19013. U.S. Census website. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19113. U.S. Census website. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. U.S. Census website. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B01003. U.S. Census website. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- "2010 Census P.L. 94-171 Summary File Data". United States Census Bureau.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- Hersko, Tyler (April 12, 2018). "New construction might help ease housing crunch in pricey Ventura County". Ventura County Star. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- staff (February 19, 2019). "Newsom puts 47 cities, including 2 Fillmore and Westlake Village, on notice over housing". Ventura County Star. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- Hersko, Tyler (February 20, 2019). "Fillmore, Westlake Village reps meet with governor for housing discussion". Ventura County Star. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- Hersko, Tyler (March 11, 2019). "After waiting list hits 10-year mark, affordable housing provider Many Mansions closes list". Ventura County Star. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- Rode, Erin (January 10, 2020). "The past decade of Ventura County housing: low supply, tight rental market, rising prices". Ventura County Star. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- Rode, Erin (March 10, 2020). "Where do Ventura County's 36,000 farmworkers live? Officials don't know". Ventura County Star. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- "OMB Bulletin No. 13-01: Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas" (PDF). United States Office of Management and Budget. February 28, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". 2012 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2013. Archived from the original (CSV) on April 1, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- "Table 2. Annual Estimates of the Population of Combined Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". 2012 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2013. Archived from the original (CSV) on May 17, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- Rode, Erin (September 13, 2019). "Ventura County lost 35,000 residents between 2013-2017. Here's a look at where they went". Ventura County Star. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- Rode, Erin (October 23, 2019). "How will cities address Ventura County's housing problem?". Ventura County Star. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- Rode, Erin (January 17, 2020). "Panel of current and former Ventura County residents discuss region's economic future". Ventura County Star. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- Biasotti, Tony (February 17, 2023). "California Lutheran University study aims to dispel myths about undocumented immigrants". Ventura County Star. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- "New lab looks to cure Huanglongbing disease carried by citrus psyllid". Ventura County Star. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- Wilson, Kathleen (August 16, 2020). "Strawberries fall in value, still king of Ventura County crops as newcomer hemp climbs onto list". Ventura County Star. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- Wilson, Kathleen. "CBD oil price likely factor in $100 million payoff predicted for Ventura County hemp crop". Ventura County Star. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- Wilson, Kathleen. "Hemp ban: Camarillo could join growing number of cities barring cultivation". Ventura County Star. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- Wilson, Kathleen (August 12, 2021). "Value of Ventura County's farm industry stays flat amid pandemic; hemp falls from list". Ventura County Star. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- Jorrey, Kyle (September 24, 2019). "Thousand Oaks proposes moratorium on hemp industry". Thousand Oaks Acorn. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- Wilson, Kathleen (November 17, 2019). "Hemp issue to be aired at Moorpark meeting of Ventura County supervisors". Ventura County Star. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- Wilson, Kathleen (November 7, 2019). "Ban on pot firms persists for unincorporated areas but perhaps not Nyeland Acres". Ventura County Star. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Wilson, Kathleen (January 15, 2020). "Half-mile buffers OK'd for schools, neighborhoods as board tightens rules on hemp". Ventura County Star. Retrieved January 18, 2020.