Blue-winged warbler

The blue-winged warbler (Vermivora cyanoptera) is a fairly common New World warbler, 11.5 cm (4.5 in) long and weighing 8.5 g (0.30 oz). It breeds in eastern North America in southern Ontario and the eastern United States. Its range is extending northwards, where it is replacing the very closely related golden-winged warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera).

| Blue-winged warbler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult male in Maine, United States | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Parulidae |

| Genus: | Vermivora |

| Species: | V. cyanoptera |

| Binomial name | |

| Vermivora cyanoptera | |

| |

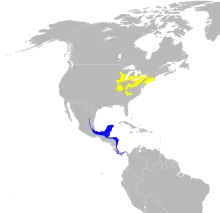

| Range of V. cyanoptera

Breeding range Winter range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

The common name blue-winged warbler refers to the bluish-gray color of the wings that contrast with the bright yellow body of the male. The name of the genus Vermivora means "worm-eating". The genus used to include nine other new world warblers but now only includes this species, the golden-winged warbler and Bachman's warbler (Vermivora bachmanii), which is believed to be extinct.

The blue-winged warbler was one of the many species originally described by Carl Linnaeus in his 18th-century work, Systema Naturae, though the scientific name has changed several times.[2] The species epithet Pinus was given by Linnaeus in 1766 but was a mistake as the original description of the species was actually based on illustrations of "pine creepers" drawn by others. The drawings depicted two different species, what we now call a pine warbler and blue-winged warbler. In 2010 the blue-winged warbler's scientific name was changed by the American Ornithologists' Union to correct the error. Pine warblers retained the species name Pinus but the species epithet for blue-winged warbler was changed to cyanoptera.[3]

Hybridization with golden-winged warbler

The blue-winged and golden-winged warblers are often compared to one another. Originally, the blue-winged warbler evolved on the interior of the continent, while the golden-winged species bred closer to the Atlantic coast.[4] However, in the recent years, their habitats have drastically changed due to urbanization, deforestation, and other factors.

Golden-winged warblers are generally more susceptible to displacement from the blue-winged warblers. One example of this can be seen in the warbler population in central New York state. In the 1980s, the blue-winged warbler significantly increased in the area while the golden-winged warbler's population decline.[5] Because of the trend, it is often assumed that the blue-winged warbler somehow causes the local extinction of the golden-winged warbler; however, molecular studies confirm that the blue-winged warbler and golden-winged warbler are sister species that diverged sometime around 1.5 million years ago.[6] Studies reveal that the two species are genetically 99.97% alike,[7] and that their main differences are their general phenotypic appearances and singing tones.

New studies also explain that the two warblers can coexist in their chosen habitat.[8] The two species can also hybridize freely where their habitats overlap, producing two hybrid types: Lawrence's warbler and Brewster's warbler.

This species forms two distinctive hybrids with the golden-winged warbler where their ranges overlap in the Great Lakes and New England area. The more common and genetically dominant Brewster's warbler is gray above and whitish (male) or yellow (female) below. It has a black eye stripe and two white wing bars. The rarer recessive Lawrence's warbler has a male plumage which is green and yellow above and yellow below, with white wing bars and the same face pattern as male golden-winged. The female is gray above and whitish below with two yellow wing bars and the same face pattern as female golden-winged.

- Song - The four species have different Song I type patterns, but primarily consist of the A-B pattern, resulting in difficulty distinguishing from one another. Their Song II type are more distinguishable from each other.[9]

- Morphology - The Brewster's warblers tend to resemble the plumage of the golden-winged but has a blue wing face pattern and variable amounts of yellow. The Lawrence's warblers look similar to blue-winged in terms of the plumage but exhibit a wing pattern similar to the golden-winged.

- Introgressed genotypes - Studies on the blue-winged and golden-winged warbler hybrids have indicated the presence of cryptic hybridization in the past for this species. This is done through DNA marker types, such as amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLPs). This may indicate that there has been repeated backcrossing between the genes in both species and their hybrid offspring.[10]

Description

The blue-winged warbler is a small warbler at 11.4–12.7 cm (4.5–5.0 in) long, with a wingspan of 17–19.5 cm (6.7–7.7 in). The breeding plumage of the male consists of a bright yellow head, breast and underparts. There is no streaking of the underparts of the bird. It has a narrow black line though the eyes and light blueish gray with two white wing-bars, which are diagnostic field marks. The blue winged warblers are generally small in size with a well-proportioned body, and heavy pointed bill. They roughly measure 4.3 to 4.7 inches long with a wingspan of around 5.9 inches. An average Blue-Winged Warbler weighs around 0.3 oz.[11]

The female is duller overall with less yellow on the crown. Immatures are olive green with wings similar to the adults.[12]

The color of their plumage tends to vary depending on the sex of the species. For males, the feathers are of bright yellow and olive green. The males often have bluish-gray wings that come with white wing bars and a distinctive black eye lining, making their heads look pointier compared to other male warbler species.[11]

Blue-winged warbler females exhibit a yellow plumage that looks a bit lighter in color. The females also have a much less prominent eye lining which mostly looks grey and light, rather than black as seen in the males.[11]

Immature or juvenile blue-winged warblers are smaller compared to adults and will show a pinkish bill and almost invisible wing bars.[6]

The song is a series of buzzing notes. The call is a sharp chip.

Distribution and habitat

Blue-winged warblers are migratory New World warblers. They winter in southern Central America and breed from east-central Nebraska in the west to southern Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan and southern Ontario in the north to central New York, southern Vermont, southern New Hampshire and New England to the east, south to western South Carolina, northern Georgia, northern Alabama, eastern Tennessee and southern Missouri.[12] It is a very rare vagrant to western Europe, with one bird wandering to Ireland.[13]

The breeding habitat is open scrubby areas. The species is mostly found in abandoned fields with shrubs and trees and bordered by tall deciduous trees.[14] Blue-winged warblers are generally found in areas located in higher elevation and high percentage of grass and canopy cover.[11]

Ecology

Diet

Diet consists of insects and spiders. Blue-winged warblers primarily feed on insects found in various plants including apple trees, walnut trees, and water hemlock. Adults sometimes hang upside down to glean and probe leaves and gather insect larvae for their young. Some examples of larvae fed to juvenile blue-winged warblers include Aphis sp., and Corythucha sp. Often, researchers presume that the species's diet and feeding methods tend to differ on each season and habitat, and may also change due to the availability of resources. This could be considered a relatively generalist species.[15]

Reproduction

Blue-winged warblers nest on the ground or low in a bush, laying four to seven eggs in a cup nest. The females incubate the eggs for 10–11 days. The young are altricial and fledge in 8–10 days.[16] The blue winged species communicate with others via singing. Hence, they have songs for fighting (descending bee-buzz), nesting, as well as breeding with other blue-winged warblers. During breeding season, the males arrive first in the location and wait for their possible mate. Usually, the females arrive one week after the males. While waiting for their mates, the males sing continuously. Once the females enter, the singing decreases and could possibly change in tune until they find a partner. After mating, the length of their song abruptly decreases.[17]

References

- BirdLife International (2018). "Vermivora cyanoptera". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22721610A132144981. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22721610A132144981.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Holmia: Laurentius Salvius. p. 187.

- Chesser, R. Terry; Banks, Richard C.; Barker, F. Keith; Cicero, Carla; Dunn, Jon L.; Kratter, Andrew W.; Lovette, Irby J.; Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Remsen, J. V.; Rising, James D.; Stotz, Douglas F.; Winker, Kevin (2010). "Fifty-First supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-List of North American Birds" (PDF). The Auk. The American Ornithologists' Union. 127 (3): 726–744. doi:10.1525/auk.2010.127.3.726. S2CID 86363169.

- Leverich, J.T. (1974). "Blue and Golden Winged Warblers and Their Hybrids". Bird Observer. 2 (3): 70–73.

- Frech, Michele H.; Confer, John L. (Spring 1987). "The Golden-Winged Warbler: Competition With The Blue-Winged Warbler And Habitat Selection In Portions Of Southern, Central And Northern New York". The Kingbird. 37 (2): 65–71.

- Gill, Frank B. (2004-10-01). "Blue-Winged Warblers (Vermivora pinus) versus Golden-Winged Warblers (V. chrysoptera)". The Auk. 121 (4): 1014–1018. doi:10.1093/auk/121.4.1014. ISSN 1938-4254.

- Toews, David P. L.; Taylor, Scott A.; Vallender, Rachel; Brelsford, Alan; Butcher, Bronwyn G.; Messer, Philipp W.; Lovette, Irby J. (2016-09-12). "Plumage Genes and Little Else Distinguish the Genomes of Hybridizing Warblers". Current Biology. 26 (17): 2313–2318. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.06.034. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 27546575. S2CID 4218758.

- Patton, Laura; Maehr, David; Duchamp, Joseph; Fei, Songlin; Gassett, Jonathan; Larkin, Jeffery (2010-10-04). "Do the Golden-winged Warbler and Blue-winged Warbler Exhibit Species-specific Differences in their Breeding Habitat Use?". Avian Conservation and Ecology. 5 (2). doi:10.5751/ACE-00392-050202. ISSN 1712-6568.

- Gill, Frank (June 1972). "Discrimination Behavior and Hybridization of the Blue Winged and Golden-Winged Warblers". Society for the Study of Evolution. 26 (2): 282–293. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1972.tb00194.x. PMID 28555732. S2CID 19704531.

- Vallender, R.; Robertson, R. J.; Friesen, V. L.; Lovette, I. J. (May 2007). "Complex hybridization dynamics between golden-winged and blue-winged warblers (Vermivora chrysoptera and Vermivora pinus) revealed by AFLP, microsatellite, intron and mtDNA markers". Molecular Ecology. 16 (10): 2017–2029. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03282.x. ISSN 0962-1083. PMID 17498229. S2CID 10622903.

- "Blue-winged Warbler Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2020-10-01.

- Terres, J. K. (1980). The Audubon Society encyclopedia of North American Birds. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 967. ISBN 0-394-46651-9.

- Chuck Kruger (2000). "Tail-end of Hurricane Sets A Record On Cape". Surfbirds.com. Archived from the original on January 7, 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-26.

- Ficken, Millicent S.; Ficken, Robert W. (1968). "Ecology of Blue-winged Warblers, Golden-winged Warblers and Some Other Vermivora". The American Midland Naturalist. 79 (2): 311–319. doi:10.2307/2423180. ISSN 0003-0031. JSTOR 2423180.

- Faxon, Walter (1913). Brewster's warbler (Helminthophila leucobronchialis) A hybrid between the golden-winged warbler (Helminthophila chrysoptera) and the blue-winged warbler (Helminthophila pinus). By Walter Faxon. Cambridge, U.S.A.: Printed for the Museum. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.14361.

- Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, D.; Wheye, D. (1988). The Birders Handbook A Field Guide to the Natural History of North American Birds. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc. p. 500. ISBN 0-671-65989-8.

- Ficken, Millicent S.; Ficken, Robert W. (1967). "Singing Behaviour of Blue-Winged and Golden-Winged Warblers and Their Hybrids". Behaviour. 28 (1/2): 149–181. doi:10.1163/156853967X00226. JSTOR 4533170.

- Curson, Jon; Quinn, David; Beadle, David (1994). Warblers of the Americas: an Identification Guide. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-70998-9.

External links

- Species account - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Species account - Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Stamps for Cuba - (incorrect range map pictured)

- Photo gallery - VIREO