Victor Noir

Victor Noir, born Yvan Salmon (27 July 1848 – 11 January 1870), was a French journalist. After he was shot and killed by Prince Pierre Bonaparte, a cousin of the French Emperor Napoleon III (r. 1852–1870), Noir became a symbol of opposition to the imperial regime. His tomb in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris has become a fertility symbol.

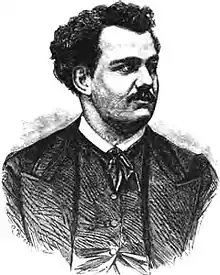

Victor Noir | |

|---|---|

Illustration of Noir, 1900 | |

| Born | Yvan Salmon July 27, 1848 Attigny, Vosges, France |

| Died | January 11, 1870 (aged 21) Auteuil, Paris, France |

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Journalist |

Early life, family and education

He was born Yvan Salmon at Attigny, Vosges, the son of a Jewish cobbler who had converted to Catholicism.

Career

He adopted "Victor Noir" as his pen name after his mother's maiden name. He moved to Paris and became an apprentice journalist for the newspaper La Marseillaise, owned and operated by Henri Rochefort and edited by Paschal Grousset.

Shooting

Background

In December 1869, a dispute broke out between two Corsican newspapers, the radical La Revanche, inspired from afar by Grousset; and the loyalist L'Avenir de la Corse, edited by an agent of the Ministry of Interior named Della Rocca. The invective of la Revanche concentrated on Napoleon I. On 30 December, l'Avenir published a letter to its editor authored by Prince Pierre Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon, and cousin of Emperor Napoleon III, who by then had ruled more than twenty years. Prince Bonaparte castigated the staff of la Revanche as cowards and traitors. The letter made its way from Bastia to Paris. Grousset took offense and demanded satisfaction. In the meantime, la Marseillaise lent strong support to the cause of la Revanche.

On 9 January 1870, Prince Bonaparte wrote a letter to Rochefort, claiming to uphold the good name of his family:

After having outraged each of my relations, you insult me with the pen of one of your menials. My turn had to come. Only I have an advantage over others of my name, of being a private individual, while being a Bonaparte... I therefore ask you whether your inkpot is guaranteed by your breast... I live, not in a palace, but at 59, rue d'Auteuil. I promise to you that if you present yourself, you will not be told that I left.[lower-alpha 1]

Shooting

On the following day, Grousset sent Victor Noir and Ulrich de Fonvielle as his seconds to fix the terms of a duel with Pierre Bonaparte. Contrary to custom, they presented themselves to Prince Bonaparte instead of contacting his seconds. Each of them carried a revolver in his pocket. Noir and de Fonvieille presented Prince Bonaparte with a letter signed by Grousset. But the prince declined the challenge, asserting his willingness to fight his fellow nobleman Rochefort, but not his "menials" (ses manœuvres). In response, Noir asserted his solidarity with his friends. According to Fonvieille, Prince Bonaparte then slapped his face and shot Noir dead. According to the Prince, it was Noir who took umbrage at the epithet and struck him first, whereupon he drew his revolver and fired at his aggressor. That was the version eventually accepted by the court.

Aftermath

A public outcry followed and on 12 January, led by political activist Auguste Blanqui, more than 100,000 people[1] joined Noir's funeral procession to a cemetery in Neuilly. Attendance in this procession was regarded as a civic duty for republicans. When Marie François Sadi Carnot endorsed electoral candidates, he often identified them as such attendees. ("Il a été au convoi de Victor Noir.")

At a time when the emperor was already unpopular, Pierre's acquittal on the murder charge caused enormous public outrage and a number of violent demonstrations.

The Franco-Prussian War resulted in the overthrow of the Emperor's regime on 4 September 1870 and the establishment of the Third Republic. In 1891 the body of Victor Noir was moved to Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

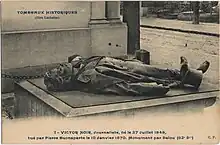

Monument

A life-sized bronze statue was sculpted by Jules Dalou to mark his grave, portrayed in a realistic style as though he had just fallen on the street, dropping his hat which is depicted beside him.

The sculpture has a very noticeable protuberance in Noir's trousers. This has made it one of the most popular memorials for women to visit in the famous cemetery. The myth says that placing a flower in the upturned top hat after kissing the statue on the lips and rubbing its genital area will enhance fertility, bring a blissful sex life, or, in some versions, a husband within the year. As a result of the legend, those particular components of the otherwise verdigris (grey-green oxidized bronze) statue are rather well-worn and shiny, as are the tips of the boots.

In 2004 a fence was erected around the statue of Noir, to deter superstitious people from touching the statue. However, due to supposed protests from the "female population of Paris", in fact led by French TV anchor Péri Cochin,[2] it was torn down again.[3]

Notes

- Après avoir outragé chacun des miens, vous m'insultez par la plume d'un de vos manœuvres. Mon tour devait arriver. Seulement j'ai un avantage sur ceux de mon nom, c'est d'être un particulier, tout en étant Bonaparte... Je viens donc vous demander si votre encrier est garanti par votre poitrine... J'habite, non dans un palais, mais 59, rue d'Auteuil. Je vous promets que si vous vous présentez, on ne vous dira pas que je suis sorti.

References

- Lissagaray, Prosper Olivier. "History of the Paris Commune of 1871". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

in January, 1870, they go 200,000 strong to the funeral of Victor Noir

- Dufour, Rémy (7 November 2004). "Contassot piégé par Ruquier devant la tombe de Victor Noir" [Contassot trapped by Ruquier at the grave of Victor Noir]. LaBandeARuquier.com (in French). Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- "'Lewd rubbing' shuts Paris statue". BBC News. 2 November 2004. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

Bibliography

- Émile Ollivier, L'empire libéral: études, récits, souvenirs, Paris: Garnier, 1908

- Pierre de La Gorce, Histoire du second empire, tome sixième, Paris: Plon, 1903

- Roger L. Williams, Manners and Murders in the World of Louis-Napoleon, Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, c.1975, 147–150. ISBN 0-295-95431-0