Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna of Russia VA CI RRC GCStJ (born Princess Victoria Melita of Edinburgh; 25 November 1876 – 2 March 1936), was the third child and second daughter of Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia. She was a granddaughter of both Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Emperor Alexander II of Russia.

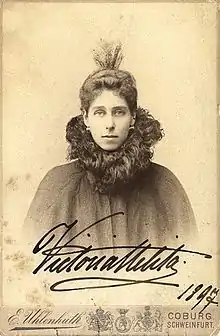

| Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | |

|---|---|

| Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna of Russia | |

Photograph by Hugo Thiele, c. 1900 | |

| Grand Duchess consort of Hesse and by Rhine | |

| Tenure | 19 April 1894 – 21 December 1901 |

| Consort to the Head of the House of Romanov | |

| Tenure | 31 August 1924 – 2 March 1936 |

| Born | Princess Victoria Melita of Edinburgh 25 November 1876 San Anton Palace, Attard, British Malta |

| Died | 2 March 1936 (aged 59) Amorbach, Nazi Germany |

| Burial | 10 March 1936 Friedhof am Glockenberg, Coburg 7 March 1995 Grand Ducal Mausoleum, Peter and Paul Fortress, Saint Petersburg |

| Spouses | |

| Issue | |

| House | Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |

| Father | Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |

| Mother | Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia |

| Religion | Russian Orthodox (1907–1936) prev. Protestant (1876–1907) |

Born a British princess, Victoria spent her early life in England and lived for three years in Malta, where her father served in the Royal Navy. In 1889 the family moved to Coburg, where Victoria's father became the reigning duke in 1893. In her teens Victoria fell in love with her first cousin Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich of Russia (the son of her maternal uncle), but his Orthodox Christian faith discouraged marriage between first cousins. Bowing to family pressure, Victoria married her paternal first cousin Ernest Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine, in 1894. The marriage failed – Victoria scandalized the royal families of Europe when she divorced her husband in 1901. The couple's only child, Princess Elisabeth, died of typhoid fever in 1903.

Victoria married Kirill in 1905. They wed without the formal approval of Britain's King Edward VII (as the Royal Marriages Act 1772 would have required), and in defiance of Russia's Emperor Nicholas II. In retaliation, the Tsar stripped Kirill of his offices and honours, also initially banishing the couple from Russia. They had two daughters, Maria and Kira, and settled in Paris before being allowed to visit Russia in 1909. In 1910 they moved to Russia, where Nicholas recognized Victoria as Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna. After the fall of the Russian monarchy in 1917 they escaped to Finland (then still part of the Russian Empire) where she gave birth to her only son, Vladimir, in August 1917. In exile they lived for some years among her relatives in Germany, and from the late 1920s on an estate they bought in Saint-Briac in Brittany. In 1926 Kirill proclaimed himself Russian emperor in exile, and Victoria supported her husband's claims. Victoria died after suffering a stroke while visiting her daughter Maria in Amorbach (Lower Franconia).

Early life

Victoria was born on 25 November 1876 in San Anton Palace in Attard, Malta, hence her second name, Melita.[1] Her father, who was stationed on the island as an officer in the Royal Navy, was Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, the second son of Queen Victoria. Her mother was Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna, the only surviving daughter of Alexander II of Russia and Marie of Hesse.

As a grandchild of the British monarch, Victoria Melita was styled Her Royal Highness Princess Victoria of Edinburgh. Within her family, she was always known as "Ducky". At the time of her birth, she was 10th in the line of succession to the British throne. The princess was christened on 1 January 1877 at San Anton Palace by a Royal Navy chaplain. Her godparents included her paternal grandmother, who was represented by a proxy.[2]

After the Duke's service in Malta was over, the family returned to England, where they lived for the next few years. They divided their time between Eastwell Park, their country home in Kent, and Clarence House, their residence in London facing Buckingham Palace. Eastwell, a large estate of 2,500 acres near Ashford, with its forest and park was the children's favorite residence.[3] In January 1886, shortly after Princess Victoria turned nine, the family left England when her father was appointed commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean naval squadron, based on Malta. For the next three years, the family lived at the San Anton Palace in Malta, Victoria's birthplace.[4]

The marriage of Victoria's parents was unhappy. The Duke was taciturn, unfaithful, prone to drinking and emotionally detached from his family. Victoria's mother was independent-minded and cultured. Although she was unsentimental and strict, the Duchess was a devoted mother and the most important person in her children's lives.[5] As a child, Victoria had a difficult temperament. She was shy, serious and sensitive. In the judgment of her sister Marie: "This passionate child was often misunderstood."[6] Princess Victoria Melita was talented at drawing and painting and learned to play the piano.[7] She was particularly close to Marie. The two sisters would remain very close throughout their lives.[8] They contrasted in appearance and personality. Victoria was dark and moody while Marie was blonde and easy-going.[6] Although she was one year younger, Victoria was taller and seemed to be the older of the two.[9]

Youth in Coburg

As a son of Queen Victoria's deceased husband, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Victoria Melita's father was in the line of succession to Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the sovereign German duchy ruled by Albert's elder brother, Ernest II, until his death in 1893. Prince Alfred became heir presumptive to the duchy when his older brother, the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), relinquished his Saxon succession rights in favour of his younger brothers. Alfred and his family therefore moved to Coburg in 1889. Their mother immediately began attempting to "Germanise" her daughters by installing a new governess, buying them plain clothing, and having them confirmed in the German Lutheran church, even though they had previously been raised as Anglicans.[10] The children rebelled and some of the new restrictions were eased.[11]

The teenage Victoria was a "tall, dark girl, with violet eyes ... with the assuredness of an Empress and the high spirits of a tomboy," according to one observer.[12] Victoria had "too little chin to be conventionally beautiful," in the opinion of one of her biographers, but "she had a good figure, deep blue eyes, and dark complexion."[13] In 1891, Victoria travelled with her mother to the funeral of her maternal aunt Grand Duchess Alexandra Georgievna of Russia. There Victoria met her first cousin Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich. Although the two were deeply attracted to each other, Victoria's mother was reluctant to allow her to marry him because the Russian Orthodox faith forbids the marriage of first cousins. She was also suspicious of the morality of the Romanov men. When her teenage daughters were impressed by their handsome cousins, their mother warned them that the Russian grand dukes did not make good husbands.[14]

Soon after her sister Marie was married to Crown Prince Ferdinand of Romania, a search was made for a suitable husband for Victoria. Her visit to her grandmother Queen Victoria at Balmoral Castle in the autumn of 1891 coincided with a visit by her cousin Prince Ernest Louis of Hesse, heir apparent to the grand ducal throne of Hesse and by Rhine. Both were artistic and fun loving, got along well and even shared a birthday. The Queen, observing this, was very keen for her two grandchildren to marry.[15]

Grand Duchess of Hesse

Eventually, Victoria and Ernest bowed to their families' pressure and married on 19 April 1894 at Schloss Ehrenburg in Coburg. The wedding was a large affair, with most of the royal families of Europe attending, including Victoria Melita's grandmother Queen Victoria, her aunt Empress Frederick of Germany, her cousin Kaiser Wilhelm II and her uncle Albert Edward, Prince of Wales. Victoria became Grand Duchess of Hesse and by Rhine, Ernest having ascended the throne in 1892.[16] Her wedding is also significant since at the same time the official engagement of the future Tsar Nicholas II of Russia to Ernst's younger sister, Alix, was proclaimed. Together Victoria and Ernst had two children, a daughter, Princess Elisabeth of Hesse and by Rhine, whom they nicknamed Ella, born on 11 March 1895, and a stillborn son, born on 25 May 1900.

Victoria and Ernest proved incompatible. Victoria despaired of her husband's lack of affection towards her, while Ernest devoted much of his attention to their daughter, whom he adored. Elisabeth, who physically resembled her mother, preferred the company of her father to Victoria.[17] Ernest and Victoria both enjoyed entertaining and frequently held house parties for young friends. Their unwritten rule was that anyone over thirty "was old and out."[18] Formality was dispensed with and royal house guests were referred to by their nicknames and encouraged to do as they wished. Victoria and Ernest cultivated friends who were progressive artists and intellectuals as well as those who enjoyed fun and frolic. Victoria's cousin Prince Nicholas of Greece and Denmark remembered one stay there as "the jolliest, merriest house party to which I have ever been in my life."[19]

Victoria was, however, less enthusiastic about fulfilling her public role. She avoided answering letters, put off visits to elderly relations whose company she did not enjoy, and talked to people who amused her at official functions while ignoring people of higher standing whom she found boring.[20] Victoria's inattention to her duties provoked quarrels with Ernst. The young couple had loud, physical fights. The volatile Victoria shouted, threw tea trays, smashed china against the wall, and tossed anything that was handy at Ernest during their arguments.[20] Victoria sought relief in her love for horses and long gallops over the countryside on a hard-to-control stallion named Bogdan.[21] While she was in Russia for the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II, Victoria's affection for Kirill was also rekindled. She enjoyed flirting with him at the balls and celebrations that marked the coronation.[22]

Divorce

Victoria and Ernest's suffered a further blow in 1897, when Victoria returned home from a visit to her sister Queen Marie of Romania and reportedly caught Ernest in bed with a male servant. She did not make her accusation public, but told a niece that "no boy was safe, from the stable hands to the kitchen help. He slept quite openly with them all."[23][24] Queen Victoria was saddened when she heard of trouble in the marriage from Sir George Buchanan, her chargé d'affaires, but refused to consent to her grandchildren's divorce because of their daughter, Elisabeth.[25] Efforts to rekindle the marriage failed and, when Queen Victoria died in January 1901, significant opposition to the end of the marriage was removed.[26]

Ernest, who had at first resisted the divorce, came to believe it was the only possible step. "Now that I am calmer I see the absolute impossibility of going on leading a life which was killing her and driving me nearly mad," Ernest wrote to his elder sister Princess Louis of Battenberg. "For to keep up your spirits and a laughing face while ruin is staring you in the eyes and misery is tearing your heart to pieces is a struggle which is fruitless. I only tried for her sake. If I had not loved her so, I would have given it up long ago."[27] Princess Louis later wrote that she was less surprised by the divorce than Ernest was. "Though both had done their best to make a success of their marriage, it had been a failure ... [T]heir characters and temperaments were quite unsuited to each other and I had noticed how they were gradually drifting apart."[27] The divorce caused scandal in the royal circles of Europe. Tsar Nicholas wrote to his mother that even death would have been better than "the general disgrace of a divorce."[28]

After her divorce, Victoria went to live with her mother at Coburg and at her house in the French Riviera.[29] She and Ernest shared custody of Elisabeth, who spent six months of each year with each parent. Elisabeth blamed Victoria for the divorce and Victoria had a difficult time reconnecting with her daughter. Ernest wrote in his memoirs that Elisabeth hid under a sofa, crying, before one visit to her mother. The Grand Duke assured the child that her mother loved her too. Elisabeth responded, "Mama says she loves me, but you do love me." Ernest remained silent and did not correct Elisabeth's impression.[17]

Elisabeth died at age eight and a half of typhoid fever during a November 1903 visit to Tsar Nicholas II and his family at their Polish hunting lodge. The doctor advised the Tsar's family to notify the child's mother of her illness, but it is rumored that the Tsarina delayed in sending a telegram. Victoria received the final telegram notifying her of the child's death just as she was preparing to travel to Poland to be at her bedside.[30] At Elisabeth's funeral, Victoria removed her Hessian Order, a medallion, and placed it on her daughter's coffin as a final gesture "that she had made a final break with her old home."[31]

Remarriage

After Victoria's divorce from Ernest, Grand Duke Kirill, whom Victoria had seen on all her subsequent visits to Russia, was discouraged by his parents from trying to keep a close relationship with her. Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna told Kirill to keep Victoria as his mistress and marry someone else.[32]

A few months later, war broke out between Russia and Japan. As a senior member of the navy, Kirill was sent on active service to the front in the Russo-Japanese War. His ship was blown up by a Japanese mine while entering Port Arthur and he was one of the few survivors. Sent home to recover, the Tsar finally allowed him permission to leave Russia and he left for Coburg to be with Victoria.[33] The narrow escape from death had hardened Kirill's determination to marry Victoria. "To those over whom the shadow of death has passed, life has a new meaning," Kirill wrote in his memoirs. "It is like daylight. And I was now within visible reach of fulfillment of the dream of my life. Nothing would cheat me of it now. I had gone through much. Now, at last, the future lay radiant before me."[34]

The couple married on 8 October 1905 in Tegernsee. It was a simple ceremony, with Victoria's mother, her sister Beatrice, and a friend, Count Adlerburg, in attendance, along with servants. The couple's uncle Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich of Russia was invited, without being told the reason, but did not arrive until after the ceremony.[35] Tsar Nicholas II responded to the marriage by stripping Kirill of his imperial allowance and expelling him from the Russian navy.[36] The Tsarina was outraged at her former sister-in-law and said she would never receive Victoria, "a woman who had behaved so disgracefully", or Kirill.[37] The couple retired to Paris, where they purchased a house off the Champs-Élysées and lived off the income provided by their parents.[38]

Victoria, who had matured as she entered her 30s,[39] decided to convert to the Russian Orthodox Church in 1907, a decision that thrilled both her mother and her husband.[40] Three days later the first of their three children, Maria Kirillovna, was born. She was named after both her grandmothers and nicknamed "Masha".[40] Their second daughter, Kira Kirillovna, was born in Paris in 1909. Victoria and Kirill, who had hoped for a son, were disappointed to have a girl, but named their daughter after her father.[41]

Grand Duchess of Russia

Nicholas II reinstated Kirill after deaths in the Russian imperial family promoted Kirill to third in the line of succession to the Russian throne. Kirill and Victoria were allowed in Russia, Victoria was granted the title of Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna,[42] and in May 1910 the couple arrived in St Petersburg.[43] The new grand duchess enjoyed entertaining at evening dinners and lavish balls attended by the cream of Saint Petersburg society.[44] Victoria had an artistic talent that she applied to home decoration in her several elaborate residences, which she arranged attractively. She decorated, gardened, and rode and also enjoyed painting, particularly watercolors.[45]

Victoria fit in within the Russian aristocracy and the circle of her mother-in-law Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna.[16] As French was frequently spoken in high circles, Victoria never completely mastered the Russian language.[46] Although she was a first cousin of both Nicholas II, on her mother's side, and to Empress Alexandra, on her father's side, the relationship with them was neither close nor warm. As Kirill became a keen auto racer, the couple often took trips by car; a favorite pastime was traveling through the Baltic provinces. Victoria dreaded the long Russian winter with its short days, and she traveled abroad, frequently visiting her sister Marie in Romania and her mother in the south of France or in Coburg. Victoria and her husband had a close relationship with their daughters, Maria and Kira. The family was spending the summer of 1914 on their yacht in the Gulf of Finland and were in Riga when the war broke out.[47]

War

During World War I, Victoria worked as a Red Cross nurse and organized a motorized ambulance unit that was known for its efficiency.[48] Victoria frequently visited the front near Warsaw and she occasionally carried out her duties under enemy fire. Kirill, for his part, was also in Poland, assigned to the naval department of Admiral Russin, member of the staff of Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich, commander in chief of the Russian army. Kirill and Victoria had always shared their relatives' distaste for the Tsar and Tsarina's friendship with the starets Grigori Rasputin.[49] The Tsarina believed Rasputin healed her son of his hemophiliac attacks with his prayers. Victoria told her sister, Queen Marie of Romania, that the Tsar's court was "looked upon as a sick man refusing every doctor and every help."[50]

When Rasputin was murdered in December 1916, Victoria and Kirill signed a letter along with other relatives asking the Tsar to show leniency to Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia, one of those implicated in the murder. The Tsar denied their request. Twice during the war Victoria visited Romania, where her sister Marie was now queen, volunteering aid for war victims. Victoria returned to Saint Petersburg in February 1917. Kirill had been appointed commander of the Naval Guards, quartered in Saint Petersburg, so he could be with his family for some time. Although publicly loyal to the Tsar, Victoria and Kirill began to meet in private with other relatives to discuss the best way to save the monarchy.

Revolution

At the end of the "February Revolution" of 1917, Tsar Nicholas II was forced to abdicate and political turmoil followed.[51] Victoria wrote to Queen Marie of Romania in February 1917 that their home was surrounded by a mob, "yet heart and soul we are with this movement of freedom which at the time probably signs our own death warrant ... We personally are losing all, our lives changed at one blow and yet we are almost leading the movement."[52] By March 1917, the revolution had spread all over Petrograd (Saint Petersburg).

Kirill led his naval unit to the Provisional Government on 14 March 1917, which was obliged to share headquarters with the new Petrograd Soviet, and swore loyalty to its leadership, hoping to restore order and preserve the monarchy. It was an action which later provoked criticism from some members of the family, who viewed it as treason.[53] Victoria supported her husband and felt he was doing the right thing.[54] She also sympathized with the people who wanted to reform the government. Kirill was forced to resign his command of the Naval Guards, but nevertheless his men remained faithful and they continued to guard Kirill and Victoria's palace on Glinka Street. Close to despair, Victoria wrote to her sister Marie of Romania that they had "neither pride nor hope, nor money, nor future, and the dear past blotted out by the frightful present; nothing is left, nothing."[55]

Anxious for their safety, Kirill and Victoria decided that the best thing to do was to leave Russia. They chose Finland as the best possible place to go. Although a territory of the Russian Empire, Finland possessed its own government and constitution, so in a way it would be like being in Russia and not being at the same time. They had already been once invited to Haikko, a beautiful estate, near Porvoo, a small town on the south coast of Finland, not far away from Helsinki. The Provisional Government permitted them to leave, though they were not allowed to take anything of value with them. They sewed jewels into the family's clothing, hoping they would not be discovered by the authorities.[56]

Exile

After two weeks in Haikko, the family moved to a rented house in Porvoo where, in August 1917, Victoria gave birth to Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich of Russia, her only son and the heir to the dynasty.[57] The family remained in Finland, a former grand duchy under Russian rule, which had declared its independence in December 1917. They hoped that the White Russians would prevail. They gradually ran out of supplies and had to beg for help from family. In July 1918, Victoria wrote to her first cousin, Crown Princess Margaret of Sweden, begging her to send baby food so she could feed Vladimir.[58] She was alienated from England because she felt her English relatives had not done enough to help the Romanovs.[59]

Victoria pleaded with her cousin King George V to help the White Russians retake the country. In a letter to the King, Lord Acton, the British minister in Helsinki, noted the toll the revolution had taken on Victoria. She "looked aged and battered and has lost much of her beauty, which is not astonishing considering all that she has gone through."[60]

After more than two years living under strained conditions, in the autumn of 1919 Victoria and Kirill left Finland and went to Germany.[61] In Munich they were reunited with Victoria's mother and the family group moved to Zurich in September 1919.[62] With the death of Victoria's mother, she inherited her villa, Chateau Fabron in Nice and her residence in Coburg, the Edinburg Palais. In the following years the exiled family divided their time between these two places.[63][64]

While in Germany, Victoria showed an interest in the Nazi Party, which appealed to her because of its anti-Bolshevik stance and her hope that the movement might help restore the Russian monarchy.[65] She attended a Nazi rally in Coburg in 1922. She was likely unaware of the most sinister aspects of the Nazi Party.[66]

Claims to the Russian throne

Kirill suffered a nervous breakdown in 1923 and Victoria nursed him back to health. She encouraged his dreams of restoring the monarchy in Russia and becoming tsar.[67] At Saint-Briac Kirill, aware of the murders of Tsar Nicholas II and his only son, officially declared himself the Guardian of the Throne in 1924.[68] Victoria went on a trip to the United States in 1924, hoping to raise American support for restoration of the monarchy.[69] Her efforts evoked little response, due to the isolationism prevalent in the United States during the 1920s.[70] She continued in her efforts to help Kirill restore the monarchy and also sold her artwork to raise money for the household.[71]

By the mid-1920s, Victoria worried over the prospects of her children. Maria, her eldest daughter, married the head of one of Germany's mediatized families, Karl, Hereditary Prince of Leiningen on 25 November 1925, Victoria's 49th birthday.[72] Victoria was at her daughter's bedside when she gave birth to her first child, Emich Kirill, in 1926[73] (later father of claimant to the Russian throne, Prince Karl Emich of Leiningen).

In the mid-1920s, the German government established relations with Moscow and the presence of Kirill and his wife, pretenders to the Russian throne, became an embarrassment.[74] Although the Bavarian government rejected pressures to expel the Russian claimant, Kirill and Victoria decided to establish their permanent residence in France.[75] In the summer of 1926 they moved to Saint-Briac on the Breton coast, where they had spent their summer vacations.[76] The remoteness of Brittany provided both privacy and security. They bought a large house on the outskirts of the town and gave it a Breton name, Ker Argonid, Villa Victoria. The resort town of Saint-Briac was a favorite spot for retired British citizens who wanted to live well on a limited income. Victoria made friends among the Britons as well as the French and other foreign residents of the town. Though at first her manner could seem haughty, residents soon discovered that Victoria was more approachable than her husband. Their friends treated them with deference, curtsying or calling them by their imperial titles.[77] They lived a secluded country life, finding it more agreeable than at Coburg.[73]

Victoria was exceedingly protective of her son Vladimir, upon whom her hopes for the future rested. She would not let him attend school because she was worried about his safety and because she wanted him to be brought up as Romanov grand dukes were prior to the revolution. Instead, she hired a tutor for him. She also refused to let him be educated for a future career.[78] In return for her devotion, Vladimir loved and respected his mother. "We adored our parents and their love for us was infinite," Vladimir wrote after their deaths. "All the hardships and bitterness we had to endure in the years were fully covered by our mutual love. We were proud of (them)."[79]

Last years

In Saint-Briac, during the summer, Kirill played golf and he and Victoria joined in picnics and excursions.[74] They were part of the social life of the community, going out to play bridge and organizing theatricals.[74] During the winter Victoria and her husband enjoyed visiting nearby Dinard and invited friends home for parties and games.[74] However, it was rumored in town that Kirill went to Paris "for the occasional fling".[80] Victoria, who had devoted her life to Kirill, was devastated when she discovered in 1933 that her husband had been unfaithful to her, according to correspondence of her sister Marie of Romania.[81] She kept up a façade for the sake of her children, including her teenage son Vladimir, but was unable to forgive Kirill's betrayal.[82] Victoria suffered a stroke soon after attending the christening of her fifth grandchild, Mechtilde of Leiningen, in February 1936. Family and friends arrived, but nothing could be done. When her closest sister reached her bedside Victoria was asked if she was glad Marie had come, to which Victoria haltingly replied, "It makes all the difference." However, she "shuddered away from Kirill's touch," wrote Marie.[83] She died on 1 March 1936. Queen Marie eulogized her sister in a letter after her death: "The whole thing was tragic beyond imagination, a tragic end to a tragic life. She carried tragedy within her – she had tragic eyes – always – even as a little girl – but we loved her enormously, there was something mighty about her – she was our Conscience."[84]

Victoria was buried in the ducal family mausoleum at Friedhof am Glockenberg in Coburg,[85]: 47 until her remains were transferred to the Grand Ducal Mausoleum of the Peter and Paul Fortress in Saint Petersburg on 7 March 1995. Her husband was intensely lonely after her death. The marriage of their daughter, Kira, to Louis Ferdinand, Prince of Prussia, in 1938 was a bright spot for Kirill, who saw it as the joining of two dynasties. However, Kirill died just two years after his wife.[86] Kirill, though he had been unfaithful, still loved and missed the wife he had depended so much upon and passed his remaining years writing memoirs of their life together.[87] "There are few who in one person combine all that is best in soul, mind, and body," he wrote. "She had it all, and more. Few there are who are fortunate in having such a woman as the partner of their lives – I was one of those privileged."[88]

Archives

Victoria Melita's letters to her sister Alexandra are preserved in the Hohenlohe Central Archive (Hohenlohe-Zentralarchiv Neuenstein) in Neuenstein Castle in the town of Neuenstein, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.[89] [90]

Honours and arms

Honours

United Kingdom:

United Kingdom:

- CI: Companion of the Imperial Order of the Crown of India, 11 December 1893[91]

- VA: Dame of the Royal Order of Victoria and Albert, 1st Class[92]

- GCStJ: Dame Grand Cross of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem[93][94]

- RRC: Member of the Royal Red Cross[48][93]

.svg.png.webp) Kingdom of Prussia: Dame of the Order of Louise, 1st Division

Kingdom of Prussia: Dame of the Order of Louise, 1st Division.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp) Ernestine duchies: Dame of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order[95]

Ernestine duchies: Dame of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order[95] Grand Duchy of Hesse:

Grand Duchy of Hesse:

- Dame of the Grand Ducal Hessian Order of the Golden Lion, in Brilliants, 19 April 1894[96]

- Dame Grand Cross of the Grand Ducal Hessian Order of Ludwig, in Brilliants, 25 November 1898[96]

- Medal of the Merit Order of Philip the Magnanimous[31]

Kingdom of Romania: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Romania

Kingdom of Romania: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Romania Russian Empire:

Russian Empire:

- Dame Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of Saint Catherine, November 1894[97]

- Decoration of the Military Order of Saint George[98]

.svg.png.webp) Restoration (Spain): Dame of the Royal Order of Noble Ladies of Queen Maria Luisa, 31 October 1913[99]

Restoration (Spain): Dame of the Royal Order of Noble Ladies of Queen Maria Luisa, 31 October 1913[99]

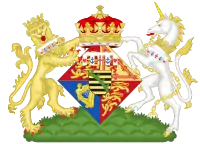

British arms

As a male-line grandchild of the British monarch, Victoria Melita bore the royal arms, with an inescutcheon for Saxony, the whole differenced by a label of five points argent, the outer pair bearing hearts gules, the inner pair anchors azure, and the central point a cross gules.[100] In 1917, the inescutcheon was dropped by royal warrant. Her arms from that point on are duplicated in the arms of Princess Alexandra, The Honourable Lady Ogilvy.

|

|---|

| Coat of arms of Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha[101] |

|---|

Notes

- Michael John Sullivan, A Fatal Passion: The Story of the Uncrowned Last Empress of Russia, Random House, 1997, p. 7

- Yvonne's Royalty Home Page — Royal Christenings Archived 6 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, uniserve.com; accessed 22 March 2014.

- Sullivan, p. 34

- Sullivan, p. 63

- John Van der Kiste, Princess Victoria Melita, Sutton Publishing, 1991, p. 15

- Sullivan, p. 37

- Sullivan, p. 56

- Sullivan, p. 38

- Van der Kiste, p. 14

- Sullivan, pp. 80–82

- Sullivan, pp. 87–88

- Sullivan, p. 115

- John Curtis Perry and Constantine Pleshakov, The Flight of the Romanovs, Basic Books, 1999, p. 83

- Sullivan, pp. 93, 114

- Sullivan, p. 113

- Sullivan, p. 126

- Sullivan, pp. 217–218

- Sullivan, p. 146

- Sullivan, p. 148

- Sullivan, p. 152

- Sullivan, p. 153

- Sullivan, p. 157

- Terence Elsberry, Marie of Romania, St. Martin's Press, 1972, p.62

- Sullivan, p. 182

- Sullivan, pp. 189–190

- Van der Kiste, pp. 60–61

- Sullivan, p. 208

- Sullivan, p. 209

- Van der Kiste, p. 81

- Sullivan, p. 223

- Sullivan, p. 224

- Charlotte Zeepvat, The Camera and the Tsars: A Romanov Family Album, Sutton Publishing, 2004, p. 107

- Sullivan, p. 229

- Sullivan, p. 230

- Sullivan, p. 233

- Sullivan, p. 236

- Sullivan, p. 237.

- Sullivan, p. 243

- Sullivan, p. 246

- Sullivan, p. 247

- Sullivan, p. 252

- See Feodorovna as a Romanov patronymic

- Sullivan, p. 253

- Sullivan, pp. 274–275.

- Sullivan, p. 262

- Sullivan, p. 254

- Sullivan, p. 283

- Sullivan, p. 288

- Sullivan, p. 271

- Sullivan, p. 272

- Sullivan, p. 313

- Zeepvat, p. 214

- Sullivan, p. 314

- Sullivan, pp. 311–312

- Van der Kiste, 105

- Sullivan, p. 321

- Sullivan, p. 325

- Sullivan, p. 333

- Sullivan, p. 341

- Perry and Pleshakov, p. 228

- Van der Kiste, p. 145

- Sullivan, p. 343

- Sullivan, p. 349

- Van der Kiste, p. 147

- Sullivan, pp. 353–354

- Sullivan, p. 354

- Sullivan, p. 355

- Sullivan, p. 357

- Sullivan, 364

- Sullivan, p. 371

- Sullivan, p. 379

- Sullivan, p. 374

- Sullivan, p. 377

- Van der Kiste, p. 163

- Sullivan, p. 375

- Sullivan, p. 376

- Perry and Pleshakov, pp. 307–308

- Van der Kiste, p. 139

- Sullivan, p. 390

- Perry and Pleshakov, p. 308

- Sullivan, p. 393

- Sullivan, p. 395

- Sullivan, 404

- Sullivan, pp. 403–404

- Klüglein, Norbert (1991). Coburg Stadt und Land (German). Verkehrsverein Coburg.

- Sullivan, pp. 406–407

- Perry and Pleshakov, p. 309

- Sullivan, p. 234

- "Briefe an Alexandra von ihrer Schwester Großherzogin Viktoria von Hessen und bei Rhein (später Großfürstin von Russland) (1876–1936), 1893–1899".

- "Briefe an Alexandra von ihrer Schwester Großherzogin Viktoria von Hessen und bei Rhein (später Großfürstin von Russland), 1900–1905".

- "No. 26467". The London Gazette. 15 December 1893. p. 7319.

- Joseph Whitaker (1897). An Almanack for the Year of Our Lord ... J. Whitaker. p. 110.

- "Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh & Saxe-Coburg Gotha (1844–1900)". 13 October 2007. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007.

- "Queen Marie of Romania (when Crown Princess) and her sister Victoria Melita, Grand Duchess of Hesse | Grand Ladies | gogm". www.gogmsite.net.

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Hessen (1900), Genealogy p. 2

- Großherzoglich Hessische Ordensliste (in German), Darmstadt: Staatsverlag, 1907, pp. 2, 5

- "Historical review of the Order of the Holy Great Martyr Catherine or the Order of Liberation". The Court Calendar for 1911. St. Petersburg: Suppliers of the Court of His Imperial Majesty. Vol. R. Golike and A. Wilborg, 1910. p. 589

- Fedorchenko, Valery. Imperial house. Outstanding dignitaries. Encyclopedia of Biographies. OLMA Media Group, 2003. 1, pp. 203–204. 1307 p. ISBN 5786700488, 9785786700481.

- "Real orden de Damas Nobles de la Reina Maria Luisa". Guía Oficial de España (in Spanish). 1914. p. 219. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- "marks of cadency in the British royal family". www.heraldica.org.

- Louda, Jiří; Maclagan, Michael (1999), Lines of Succession: Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe, London: Little, Brown, p. 34, ISBN 978-1-85605-469-0

Bibliography

- Van der Kiste, John. Princess Victoria Melita, Sutton Publishing, 1991, ISBN 0-7509-3469-7

- Maylunas, Andrei and Sergei Mironenko. A Lifelong Passion: Nicholas and Alexandra: Their Own Story, Doubleday, 1997, ISBN 0-385-48673-1

- Perry, John Curtis and Constantine Pleshakov. The Flight of the Romanovs, Basic Books, 1999, ISBN 978-0-465-02462-9

- Sullivan, Michael John. A Fatal Passion: The Story of the Uncrowned Last Empress of Russia, Random House, 1997, ISBN 0-679-42400-8

- Zeepvat, Charlotte. The Camera and the Tsars: A Romanov Family Album, Sutton Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-7509-3049-7

External links

- "Victoria Melita of Edinburgh (1876–1936)" at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 October 2009), by Jesus Ibarra.

- Portraits of Victoria Melita, Grand Duchess of Russia at the National Portrait Gallery, London