Violence against women in India

Violence against women in India refers to physical or sexual violence committed against a woman, typically by a man. Common forms of violence against women in India include acts such as domestic abuse, sexual assault, and murder. In order to be considered violence against women, the act must be committed solely because the victim is female. Most typically, these acts are committed by men as a result of the long-standing gender inequalities present in the country.

| Part of a series on |

| Violence against women |

|---|

| Killing |

| Sexual assault and rape |

| Disfigurement |

| Other issues |

| International legal framework |

| Related topics |

It is actually more present than it may appear at first glance, as many expressions of violence are not considered crimes, or may otherwise go unreported or undocumented due to certain Indian cultural values and beliefs. Many women agree that their husband beating them is justified.[1][2] India's Gender Gap Index rating was 0.629 in 2022, placing it in 135th place out of 146 countries.[3]

Extent

| Year | Reported violence[4] |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 195,856 |

| 2009 | 203,804 |

| 2010 | 213,585 |

| 2011 | 228,650 |

| 2012 | 244,270 |

According to the National Crime Records Bureau of India, reported incidents of crime against women increased by 15.3% in 2021 compared to the year 2020.[5] According to the National Crime Records Bureau, in 2011, there were more than 228,650 reported incidents of crime against women, while in 2021, there were 4,28,278 reported incidents, an 87% increase.[6]

Of the women living in India, 7.5% live in West Bengal where 12.7% of the total reported crime against women occurs.[4] Andhra Pradesh is home to 7.3% of India's female population and accounts for 11.5% of the total reported crimes against women.[4]

65% of Indian men believe women should tolerate violence in order to keep the family together, and women sometimes deserve to be beaten.[7] In January 2011, the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES) Questionnaire reported that 24% of Indian men had committed sexual violence at some point during their lives.[7]

Exact statistics on the extent case occurrences are very difficult to obtain, as a large number of cases go unreported. This is due in large part to the threat of ridicule or shame on the part of the potential reporter, as well as an immense pressure not to damage the family's honour.[8][9] For similar reasons, law enforcement officers are more motivated to accept offers of bribery from the family of the accused, or perhaps in fear of more grave consequences, such as Honour killings[8]

Murders

Dowry deaths

A dowry death is the murder or suicide of a married woman caused by a dispute over her dowry.[10] In some cases, husbands and in-laws will attempt to extort a greater dowry through continuous harassment and torture which sometimes results in the wife committing suicide,[11] or the exchange of gifts, money, or property upon marriage of a family's daughter.

The majority of these suicides are done through hanging, poisoning or self-immolation. When a dowry death is done by setting the woman on fire, it is called bride burning. Bride burning murder is often set up to appear to be a suicide or accident, sometimes by setting the woman on fire in such a way that it appears she ignited while cooking at a kerosene stove.[8] Dowry is illegal in India, but it is still common practice to give expensive gifts to the groom and his relatives at weddings which are hosted by the family of the bride.[12]

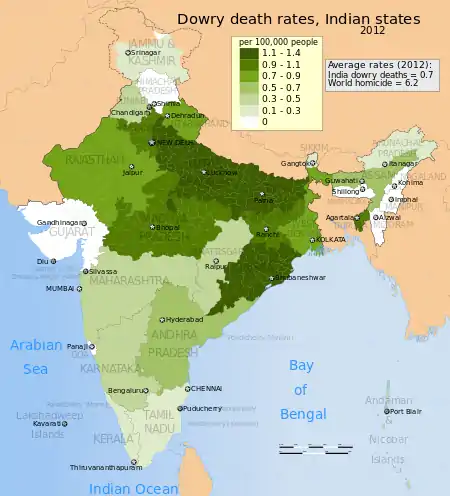

According to National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data, 6,589 dowry deaths were registered in the year 2021 all over the country, a 3.85% decline from 2020, with highest number of dowry deaths from the state of Uttar Pradesh(2,222 dowry deaths) and highest dowry death rate(per 1,00,000 population) in the state of Haryana.[13][14][15]

| Year | Reported dowry deaths[4] |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 8,172 |

| 2009 | 8,383 |

| 2010 | 8,391 |

| 2011 | 8,618 |

| 2012 | 8,233 |

| 2020 | 6,843[14] |

| 2021 | 6,589[13] |

Honour killings

A honour killing is a murder of a family member who has considered to have brought dishonour and shame upon the family.[16] Examples of reasons for honour killings include the refusal to enter an arranged marriage, committing adultery, choosing a partner that the family disapproves of, and becoming a victim of rape.[17] Village caste councils or khap panchayats in certain regions of India regularly pass death sentences for persons who do not follow their diktats on caste or gotra.[18] The volunteer group known as Love Commandos from Delhi, runs a helpline dedicated to rescuing couples who are afraid of violence for marrying outside of caste lines.[18]

The most prominent areas where honour killings occur in India are the northern states—they're especially numerous in Haryana, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh.[19][20] Honour killings have notably increased in some Indian states which has led to the Supreme Court of India, in June 2010, issuing notices to both the Indian central government and six states to take preventative measures against honour killings.[21]

Honour killings can be very violent. For example, in June 2012, a father decapitated his 20-year-old daughter with a sword upon hearing that she was dating a man who he did not approve of.[22][23]

Honour killings can also be openly supported by both local villagers and neighbouring villagers. This was the case in September 2013, when a young couple who married after having a love affair were brutally murdered.[24]

Witchcraft-related murders

Murders of women accused of witchcraft still occur in India.[25][26][27] Poor women, widows, and women from lower castes are most at risk of such killings.[28]

Female infanticide and sex-selective abortion

Female infanticide is the selected killing of a newborn female child or the termination of a female fetus through sex-selective abortion. In India, there is incentive to have a son, because they offer security to the family in old age and are able to conduct rituals for deceased parents and ancestors.[29] In contrast, daughters are considered to be a social and economic burden.[29] An example of this is dowry. The fear of not being able to pay an acceptable dowry and becoming socially ostracised can lead to female infanticide in poorer families.[30] Pew Research Centre estimated as many as 9 million females missing from Indian population in the period 2000-2019 according to Indian government data.[31]

Modern medical technology has allowed for the sex of a child to be determined while the child is still a fetus.[32][33] Once these modern prenatal diagnostic techniques determine the sex of the fetus, families then are able to decide if they would like to abort based on sex. One study found that 7,997 of 8,000 abortions were of female fetuses.[8] The fetal sex determination and sex-selective abortion by medical professionals is now a R.s 1,000 crore (US$244 million) industry.[34]

The Preconception and Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques Act of 1994 (PCPNDT Act 1994) was modified in 2003 in order to target medical professionals.[34] The Act has proven ineffective due to the lack of implementation. Sex-selective abortions have totaled approximately 4.2-12.1 million from 1980 to 2010.[35] There was a greater increase in the number of sex-selective abortions in the 1990s than the 2000s.[35] Poorer families are responsible for a higher proportion of abortions than wealthier families.[36] Significantly more abortions occur in rural areas versus urban areas when the first child is female.[36]

Sexual crimes

Rape

India is perceived as one of the world's most dangerous countries for sexual violence against women.[39] Rape is one of the most common crimes in India. Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013 defines rape as penile and non-penile penetration in bodily orifices of a woman by a man, without the consent of the woman.[40] According to the National Crime Records Bureau, one woman is raped every 20 minutes in India.[41] Incidents of reported rape increased 3% from 2011 to 2012.[4] Incidents of reported incest rape increased 46.8% from 268 cases in 2011 to 392 cases in 2012.[4] Despite its prevalence, rape accounted for 10.9% of reported cases of violence against women in 2016.[9]

| Year | Reported rapes[4][42] |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 21,467 |

| 2009 | 21,397 |

| 2010 | 22,172 |

| 2011 | 24,206 |

| 2012 | 24,923 |

| 2013 | 34,707 |

| 2014 | 36,735 |

| 2015 | 34,651 |

| 2016 | 38,947[43] |

| 2017 | 32,599[44] |

| 2018 | 33,356[45] |

| 2019 | 32,033[46] |

| 2020 | 28,046[47] |

| 2021 | 31,677[48] |

Victims of rape are increasingly reporting their rapes and confronting the perpetrators. Women are becoming more independent and educated, which is increasing their likelihood to report their rape.[49]

Although rapes are becoming more frequently reported, many go unreported or have the complaint files withdrawn due to the perception of family honour being compromised.[49] Women frequently do not receive justice for their rapes, because police often do not give a fair hearing, and/or medical evidence is often unrecorded which makes it easy for offenders to get away with their crimes under the current laws.[49]

Increased attention in the media and awareness among both Indians and the outside world is both bringing attention to the issue of rape in India and helping empower women to report the crime. After international news reported the gang rape of a 23-year-old student on a moving bus that occurred in Delhi, in December 2012, Delhi experienced a significant increase in reported rapes. The number of reported rapes nearly doubled from 143 reported in January–March 2012 to 359 during the three months after the rape. After the Delhi rape case, Indian media has committed to report each and every rape case.[50] Self defense programs[51] run by NGOs like Survival Instincts[52] and Krav Maga Global (KMG) were made mandatory in corporate organizations, and the International Women's Day programs[53] started focussing on improving women's safety in workplaces, commute and homes.

Marital rape

In India, marital rape is not a criminal offense.[54] India is one of fifty countries that have not yet outlawed marital rape.[55] 20% of Indian men admit to forcing their wives or partners to have sex.[7] Marital rape of an adult wife, who is unofficially or officially separated, is a criminal offence punishable by 2 to 7 year in prison; it is not dealt by normal rape laws which stipulate the possibility of a death sentence.[56]

Marital rape can be classified into one of three types:[57]

- Battering rape: This includes both physical and sexual violence. The majority of marital rape victims experience battering rape.

- Force-only rape: Husbands use the minimum amount of force necessary to coerce his wife.

- Compulsive or obsessive rape: Torture and/or "perverse" sexual acts occur and are often physically violent.

Insult to modesty

| Year | Assaults with intent to outrage modesty | Insults to the modesty of women[4][42] |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 40,413 | 12,214 |

| 2009 | 38,711 | 11,009 |

| 2010 | 40,613 | 9,961 |

| 2011 | 42,968 | 8,570 |

| 2012 | 45,351 | 9,173 |

| 2013 | 70,739 | 12,589 |

| 2014 | 82,235 | 9,735 |

| 2015 | 82,422 | 8,685 |

Modesty-related violence against women includes assaults on women with intent to outrage her modesty are insults to the modesty of women. From 2011 to 2012, there was a 5.5% increase in reported assaults on women with intent to outrage her modesty.[4] Madhya Pradesh had 6,655 cases, accounting for 14.7% of the national incidents.[4] From 2011 to 2012, there was a 7.0% increase in reported insults to the modesty of women.[4] Andhra Pradesh had 3,714 cases, accounting for 40.5% of the national accounts, and Maharashtra had 3,714 cases, accounting for 14.1% of the national accounts.[4]

Human trafficking and forced prostitution

| Year | Imported girls from foreign countries | Violations of the Immoral Traffic Act[4][42] |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 67 | 2,659 |

| 2009 | 48 | 2,474 |

| 2010 | 36 | 2,499 |

| 2011 | 80 | 2,435 |

| 2012 | 59 | 2,563 |

| 2013 | 31 | 2,579 |

| 2014 | 13 | 2,070 |

| 2015 | 6 | 2,424 |

From 2011 to 2012, there was a 26.3% decrease in girls imported to India from another country.[4] Karnataka had 32 cases, and West Bengal had 12 cases, together accounting for 93.2% of the total cases nationwide.[4]

From 2011 to 2012, there was a 5.3% increase in violations of the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act of 1956.[4] Tamil Nadu had 500 incidents, accounting for 19.5% of the total nationwide, and Andhra Pradesh had 472 incidents, accounting for 18.4% of the total nationwide.[4]

Domestic violence

Domestic violence is abuse by one partner against another in an intimate relationship such as dating, marriage, cohabitation or a familial relationship. Domestic violence is also known as domestic abuse, spousal abuse, battering, family violence, dating abuse and intimate partner violence (IPV). Domestic violence can be physical, emotional, verbal, economic and sexual abuse. Domestic violence can be subtle, coercive or violent. As politician Renuka Chowdhury says, in India, 70% of women are victims of domestic violence.[41]

National Family Health Survey (NFHS) in 2016 found that 86% of Indian women did not report domestic violence to anyone, not even to friends and family members. Many women victims justify the domestic violence, mainly due to social norms which lead them to believe that they are not good wives and deserve punishment. A survey found that 45% of Indian women justify their husbands beating them. National Family Health Survey (2019–21) reveals that in four southern states, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, 80% of wives agree that their husbands are justified in beating them, which is high, compared to other Indian states.[58][59][1][2] 38% of Indian men admit they have physically abused their partners.[7] The Indian government has taken measures to try to reduce domestic violence through legislation such as the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act 2005.[41]

| Year | Reported cruelty by a husband or relative[4][42] |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 81,344 |

| 2009 | 89,546 |

| 2010 | 94,041 |

| 2011 | 99,135 |

| 2012 | 106,527 |

| 2013 | 118,866 |

| 2014 | 122,877 |

| 2015 | 113,403 |

Every 9 minutes, a case of cruelty is committed by either husband or a relative of the husband.[41] Cruelty by a husband or his relatives is the greatest occurring crime against women. From 2011 to 2012, there was a 7.5% increase in cruelty by husbands and relatives.[4]

The Other Perspective – Abuse of Section 498A in India

On one hand, section 498A of the Indian Penal Code safeguards Indian women from crimes committed by their husbands and the husband's relatives against ‘dowry’. On the other, a majority of women in India have been found abusing the law. The testament to the same is the extremely low conviction rate under the said act; which was reported to be mere 12.1%. The surge in the misuse has been quite significant in the past couple of years.

Forced child marriage

Girls are vulnerable to being forced into marriage at young ages, suffering from a double vulnerability: both for being a child and for being female. Child brides often do not understand the meaning and responsibilities of marriage. Causes of such marriages include the view that girls are a burden for their parents, and the fear of girls losing their chastity before marriage.[60]

Around 7.84 million female children under the age of 10 are married in India.[61]

Acid throwing

Acid throwing, also called an acid attack, a vitriol attack or vitriolage, is a form of violent assault used against women in India.[62] Acid throwing is the act of throwing acid or an alternative corrosive substance onto a person's body "with the intention to disfigure, maim, torture, or kill."[63] Acid attacks are usually directed at a victim's face which burns the skin causing damage and often exposing or dissolving bone.[64][65] Acid attacks can lead to permanent scarring,[66] blindness, as well as social, psychological and economic difficulties.[63]

The Indian legislature has regulated the sale of acid.[67] Compared to women throughout the world, women in India are at a higher risk of being victims of acid attacks.[68] At least 72% of reported acid attacks in India have involved women.[68] India has been experiencing an increasing trend of acid attacks over the past decade.[68]

In the period of 5 years between 2014 and 2018, 1,483 victims of acid attacks were registered, according to the National Crime Records Bureau data, in the country. The number of acid attacks are rising, but there is decline in number of people chargesheeted by the police. Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Delhi make up 42% of all the victims of acid attacks in India. The perpetrator rarely gets punishment. For example, in 2015, 734 cases went to trial, only 33 cases resulted in completion.[69]

In 2018, Zainul Abideen ran 720 km golden triangle India (Delhi to Agra to Jaipur) against Acid/Rape attack for more awareness in public for women safety.[70]

Abduction

| Year | Reported abductions[4][42] |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 22,939 |

| 2009 | 25,741 |

| 2010 | 29,795 |

| 2011 | 35,565 |

| 2012 | 38,262 |

| 2013 | 51,881 |

| 2014 | 57,311 |

| 2015 | 59,277 |

Incidents of reported kidnappings and abductions of women accounted for 17.6% of crimes against women in 2021, according to government data.[71] A total of 28,000 women were abducted in 2021 for forced marriage.[72]

Perpetuation

The perpetuation of violence against women in India continues as a result of many systems of sexism and patriarchy in place within Indian culture. Beginning in early childhood, young girls are given less access to education than their male counterparts. 80% of boys will go to primary school, whereas just over half of the girls will have that same opportunity.[8] Gender-based inequality is present even before that, however, as it is reported that female children are often fed less and are given less hearty diets that contain little to no butter, milk, or other more hearty foods.[8] Even when girls are taught about the inequity they will face in life, boys are uneducated on this and are therefore unprepared to treat women and girls as equals.[9]

Later in life, the social climate continues to reinforce inequality, and consequently, violence against women. Married women in India tend to see violence as a routine part of being married.[9] Women who are put in a situation where they are being subjected to gender-based violence are often victim shamed, being told that their safety is their own responsibility and that whatever may happen to them is their own fault.[9] In addition to this, women are very heavily pressured into complicity because of social and cultural beliefs, such as family honour.

Even when a woman who is a victim of gender-based violence or crime does decide to report the incident, it is not always likely that she will have access to the support she would need to handle the situation properly. Law enforcement officers and doctors will often choose not to report a case, due to fear that it might in some way damage their own honour, or otherwise bring shame to them.[73] In the case that she gets help from a doctor, there is no standard procedure for determining whether a woman is a victim of Sexual assault and doctors often resort to highly invasive and primitive methods such as the infamous "two-finger test" which can worsen the problem and can be psychologically damaging for the victim.[73]

Some organizations exist to help end the perpetuation of violence against women in India, most notably Dilaasa, a hospital-based crisis center for women operated in collaboration with CEHAT with aims to provide proper care for survivors of violence against women and work towards ending gender inequality. From 2000 to 2013, about 3,000 victims of sexual assault, domestic abuse, or other forms of gender-based violence have registered with Dilaasa.[74][73]

See also

References

- Ghosh, Sreeparna (2011). "Watching, Blaming, Silencing, Intervening: Exploring the Role of the Community in Preventing Domestic Violence in India". Practicing Anthropology. 33, no.3 (Anthropological Encounters with Intimate Partner Violence: Reflections on our Roles in Advocating for a Safer World (Summer 2011)): 22–26. doi:10.17730/praa.33.3.0308216293212j00. JSTOR 24781961. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- Varghese, Rebecca Rose; Radhakrishnan, Vignesh; Sundar, Kannan (2022-03-09). "Silent survivors in the South". The Hindu. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- Misra, Udit (2022-07-14). "Explained: How gender equal is India as per the 2022 Global Gender Gap Index?". The Indian Express. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- "Crimes Against Women" (PDF). Ncrb.gov.in. National Crime Records Bureau. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-09-18. Retrieved 2014-03-02.

- "Crimes against women rose 15.3% in 2021, Delhi most unsafe: Key takeaways of NCRB report". First Post. 2022-08-30. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- "Nearly 20% Increase in Rapes Across India in 2021, Rajasthan Had Highest Cases: NCRB". The Wire. 2022-08-30. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- "International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES)". ICRW.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-27. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- Peters, Julie; Wolper, Andrea, eds. (2018-05-11). Women's Rights, Human Rights. doi:10.4324/9781315656571. ISBN 978-1-315-65657-1.

- Menon, Suvarna V.; Allen, Nicole E. (2018-09-01). "The Formal Systems Response to Violence Against Women in India: A Cultural Lens". American Journal of Community Psychology. 62 (1–2): 51–61. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12249. ISSN 1573-2770. PMID 29693250.

- "dowry death: definition of dowry death in Oxford dictionary (American English) (US)". Oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- Oldenburg, V. T. (2002). Dowry murder: The imperial origins of a cultural crime. Oxford University Press.

- Shah, Harmeet (2014-02-03). "Indian woman and baby burned alive for dowry, police say". CNN.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- Roy, Esha (2022-08-30). "Crime against women rose by 15.3% in 2021: NCRB". The Indian Express. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- Rajkumar, Akchayaa (2022-08-30). "25% rise in dowry cases in 2021, reveals NCRB data". The News Minute. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- Thakur, Bhartesh Singh (2022-08-29). "Haryana has highest dowry death rate in country: NCRB". The Tribune. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- "honour killing – definition of honour killing in English from the Oxford dictionary". Oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- "Ethics – Honour crimes". BBC. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- Chamberlain, Gethin (2010-10-09). "Honour killings: Saved from India's caste system by the Love Commandos". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- "India court seeks 'honour killing' response". BBC News. 2010-06-21. Archived from the original on 2016-07-17. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- "What Justice?". BBC World Service. Archived from the original on 2012-11-06. Retrieved 2014-04-14.

- Mahapatra, Dhananjay (June 21, 2010). "Honour killing: SC notice to Centre, Haryana and 6 other states". Times of India. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- Bhandari, Prakash (June 18, 2012). "Indian Man Beheads Daughter in Rage Over Lifestyle". NBC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 19, 2018. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- "Man beheads daughter in gory Rajasthan". Zee News. IANS. June 17, 2012. Archived from the original on December 19, 2018. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- "India 'honour killings': Paying the price for falling in love". BBC News. September 20, 2013. Archived from the original on December 19, 2018. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- "India woman killed in 'witch hunt'". BBC News. 2014-10-27. Archived from the original on 2015-10-16. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- "Indian villagers arrested over 'heinous' witchcraft murder – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Abc.net.au. 2013-06-09. Archived from the original on 2016-10-31. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- McCoy, Terrence (2014-07-21). "Thousands of women, accused of sorcery, tortured and executed in Indian witch hunts". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2016-03-15. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- "Witch Hunting in India: Poor, Low Caste and Widows Main Targets". Ibtimes.co.uk. 2014-07-22. Archived from the original on 2015-12-25. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- Ahmad, N (2010). "Female feticide in India". Issues in Law & Medicine. 26 (1): 13–29. PMID 20879612.

- Oberman, Michelle (2005). "A Brief History of Infanticide and the Law". In Margaret G. Spinelli. Infanticide Psychosocial and Legal Perspectives on Mothers Who Kill (1st ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. ISBN 1-58562-097-1.

- Kaur, Banjot (2022-09-06). "Foeticide: More 'Missing' Girls Among Hindus Than Muslims in Last Two Decades, Official Data Shows". The Wire. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- George, Sabu M.; Dahiya, Ranbir S. (1998). "Female Foeticide in Rural Haryana". Economic and Political Weekly. 33 (32): 2191–8. JSTOR 4407077.

- Luthra, Rashmi (1994). "A Case of Problematic Diffusion: The Use of Sex Determination Techniques in India" (PDF). Science Communication. 15 (3): 259–72. doi:10.1177/107554709401500301. hdl:2027.42/68396. S2CID 143653663.

- "Female foeticide in India". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 2014-12-23. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- Banthia, J. K.; Jha, P.; Kesler, M. A.; Kumar, R.; Ram, F.; Ram, U.; Aleksandrowicz, L.; Bassani, D. G.; Chandra, S. (2011). "Trends in selective abortions of girls in India: analysis of nationally representative birth histories from 1990 to 2005 and census data from 1991 to 2011" (PDF). Unfpa.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-04-15. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- Aithal, U. B. (2012). A statistical analysis of female foeticide with reference to kolhapur district. International Journal of Scientific Research Publications, 2(12), doi: ISSN 2250-3153

- Crime in India 2012 Statistics Archived 2014-06-20 at the Wayback Machine, National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt of India, Table 5.1, page 385.

- Intimate Partner Violence, 1993–2010 Archived 2014-07-28 at the Wayback Machine, Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Department of Justice, table on page 10.

- "The world's most dangerous countries for women". Thomson Reuters Foundation. Archived from the original on 14 March 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- "India: Criminal Law Amendment Bill on Rape Adopted | Global Legal Monitor". Loc.gov. 2013-04-09. Archived from the original on 2014-04-09. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- "India tackles domestic violence". BBC News. 26 October 2006. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- "Chapter 5: Crimes Against Women, NCRB Crime in India 2014" (PDF).

- Tiwary, Deeptiman (2017-12-01). "NCRB Data, 2016: Cruelty by husband, sexual assault, top crimes against women". The Indian Express. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "In 2017, rape cases were lowest in 4 yrs: NCRB data". Hindustan Times. 2019-10-24. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "Average 80 Murders, 91 Rapes Daily in 2018: NCRB Data". The Wire. 2020-01-10. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "Average 87 Rape Cases Daily, Over 7% Rise in Crimes Against Women in 2019: NCRB Data". The Wire. 2020-09-30. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "80 Murders, 77 Rape Cases Daily In 2020: What Report Reveals About Crime In India". NDTV. 2021-09-16. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "Nearly 20% Increase in Rapes Across India in 2021, Rajasthan Had Highest Cases: NCRB". The Wire. 2022-08-30. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- Sudha G Tilak (2013-03-11). "Crimes against women increase in India". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on 2016-04-14. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- Bhowmick, Nilanjana (2013-11-08). "Rape In India: Why It Seems Worse". Time. Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- "Women make a beeline for self-defence classes". The Times of India. 2013-01-09. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- "Self-defence techniques being taught to women in Chennai". The Hindu. 2016-06-14. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- "'Trust your gut instinct – it is always right'". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- Kinnear, Karen L. (2011). Women in Developing Countries: A Reference Handbook. ABC-CLIO. pp. 26–27. ISBN 1598844261.

- Lodhia, Sharmila (2015). "From 'living corpse' to India's daughter: Exploring the social, political and legal landscape of the 2012 Delhi gang rape". Women's Studies International Forum. 50: 89–101. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2015.03.007.

- jain, akanksha (2018-01-17). "Marital Rape: Married, Married But Separated, & Unmarried-Classifying Rape Victims Is Unconstitutional: Petitioners Submit Before Delhi HC [Read Written Submissions]". www.livelaw.in. Retrieved 2019-03-23.

- Pandey, Pradeep Kumar, Marital Rape in India – Needs Legal Recognition (July 4, 2013).

- Jacob, Suraj; Chattopadhyay, Sreeparna (2021-07-06). "When It Comes To Dismissing Marital Violence, Aren't We All Josephines?". The Wire). Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- "Most Dangerous Countries for Women 2022". World Population Review. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 7, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "India Has 12 Million Married Children Under Age Ten". The Wire. 2016-06-01. Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- Karmakar, R.N. (2003). Forensic Medicine and Toxicology. Academic Publishers. ISBN 81-87504-69-2.

- "Breaking the Silence: Addressing Acid Attacks in Cambodia". Cambodian Acid Survivors Charity. May 2010. pp. 1–51. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Swanson, Jordan (2002). "Acid attacks: Bangladesh's efforts to stop the violence". Harvard Health Policy Review. 3 (1): 1–4.

- Welsh, Jane (2009). 'It was like a burning hell': A Comparative Exploration of Acid Attack Violence (Thesis). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. pp. 19–21. OCLC 950539215.

- Bandyopadhyay, Mridula and Mahmuda Rahman Khan, 'Loss of face: violence against women in South Asia' in Lenore Manderson, Linda Rae Bennett (eds) Violence Against Women in Asian Societies (Routledge, 2003), ISBN 978-0-7007-1741-5

- "India's top court moves to curb acid attacks". Al Jazeera English. 2013-07-18. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- Avon Global Center for Women and Justice at Cornell Law School; Committee on International Human Rights of the New York City bar Association, Cornell Law School international Human Rights Clinic,; the Virtue Foundation (2011). "Combating Acid Violence In Bangladesh, India, and Cambodia". Avon Foundation for Women. pp. 1–64. Retrieved 20 March 2014

- Roy, Pulaha (2020-01-12). "India saw almost 1,500 acid attacks in five years". India Today. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- "FASTEST TO COVER GOLDEN TRIANGLE ON FOOT FOR A SOCIAL CAUSE". IBR. 2021-01-05. Retrieved 2021-06-12.

- "Crimes against women rose 15.3% in 2021, Delhi most unsafe: Key takeaways of NCRB report". Firstpost. 2022-08-30. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- "How safe are women in India? NCRB data shows over 15% rise in crime against women in 2021". The Financial Express. 2022-08-30. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- Yee, Amy (2013). "Reforms urged to tackle violence against women in India". The Lancet. 381 (9876): 1445–1446. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60912-5. PMID 23630984. S2CID 40956164.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). www.cehat.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-06-26. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Kumar Kharwar, Shiv; Kumar, Vivek (2021). "Crimes Against Women In The 21st Century". International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Explorer. 1 (1). Retrieved 23 June 2022.