Visions of Amram

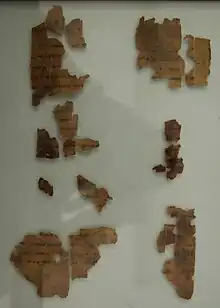

Visions of Amram, also referred to as 4Q543-549, is a collection of five extremely fragmented copies found in Qumran cave 4. In 1972, Jozef T. Milik published a significant fragment of the Visions of Amram.[1] Since then, controversy has surrounded this document at every turn. In this testament, Amram gathers his sons, Moses and Aaron, to his deathbed and relates stories of his life, providing wisdom and commanding understanding.[2] This document is named for a vision shared during this time.

.jpg.webp)

This document has many distinguishing features that separate it from the other Dead Sea Scrolls found in the Qumran Caves. Primarily, copies of Visions of Amram are written in Aramaic,[1] unlike the majority of the Qumran texts which were scripted in Hebrew. This unique feature, along with its suspected dating to the second century BCE, leads most scholars to believe these documents were written prior to and apart from the Qumran sectarian documents.[3] Due to the multiple copies, organization and comprehension of this fragmented document is two-fold. 1) First, fragments are categorized into five groups based on manuscript, creating pieces of a whole, yet incomprehensible, document. 2) Secondly, fragments are overlapped and mixed to create a single, somewhat coherent, account. Unfortunately, this document is far from complete. Vast sections of this account have been put together through intensive reconstruction, leading to controversy and further uncertainties.

Manuscript content

Upon the year of his death (136 years old), Amram, (son of Kohath, son of Levi)[2] gave in marriage his 30-year-old daughter, Miriam, to his brother, Uzziel. The wedding was 7 days long. After the feast, Amram called for his children and began to recollect the story of his time in Biblical Egypt. Amram tells his son Aaron to summon his son Malachijah. Then Amram tells him that he will give them wisdom. Amram and Kohath went to Canaan from Egypt to build tombs for those who perished during the Egyptian sojourn. Amram stayed in Canaan to finish the tombs, while Kohath left for Egypt due to the threat of war. Amram was unable to go back to his wife and family in Egypt for 41 years, until the war between Egypt, Canaan and Philistia was over [2]

Next, Amram presents his vision. He accounts two divine figures fighting over the fate of his judgement. Amram inquires about their claimed authority and challenges their rule in his life. In apparent unison, the figures declare their rule over humanity, and offer him a choice of destiny. One presents himself as Belial, Prince of Darkness, and Melkirisha, King of Evil, who is empowered over all Darkness.[4] The other figure, dubbed Melchizedek, Prince of Light and King of Righteousness, rules over the Light.[4] Amram tells his audience that he wrote down his vision as soon as he awoke.[2]

Amram also differentiates between light and darkness. He tells his audience that the Sons of Light will be made light and Sons of Darkness will be made dark.[4] Sons of Light are destined for light and joy, while Sons of Darkness are destined for death and darkness.[4] It fundamentally explains how light will triumph over darkness, and it is declared that the Son of Darkness will be destroyed.[4]

Type of literature

The type of genre of the Visions of Amram is decided according to common features found in relation to other texts. However, according to Jorg Frey, there needs to be room for uniqueness and character.[5] It is essential to use different types of scholarly genres to categorize the texts, even though ancient authors did not use them or used them quite differently.[5] This is a reason why there is ambiguity surrounding whether or not the Visions of Amram are classified as "testaments" or "visions".

Jean Starcky was the first to believe that the Visions fall under the testament genre, because of the multiple similarities with the Testament of Levi.[6] Here scholars compared the introductory narrative of the Visions of Amram with the introductory sections of the Testaments of the 12 Patriarchs, most specifically the Testament of Levi.[7] Officially, Józef Milik was the first to call the Visions of Amram a testament.[6]

However, people began to question why the author called it the Visions of Amram and not the Testament of Amram.[5] Here, differing views started to emerge and the world "testament" used to describe the Visions, slowly began to disappear.[7] Furthermore, John J. Collins, pointed out how the introductory narrative does not have the usual format of a testament. Instead it has a summary heading.[7] Collins would say that it is a vision of the demonic Melchiresha and its angel counterpart.[7] Similarly, Henryk Drawnel would say that the genre of the visions seems to be didactic.[8]

Dualism in Visions of Amram

It is relatively certain that Visions of Amram originated well before the scribes of Qumran, and likely existed beyond this community.[3] Nevertheless, based on the evidence of multiple copies found fragmented in cave 4, this text appears to have been significant to the people of Qumran.[9] Although never explicitly referenced in Qumran sectarian literature,[1] Amram's vision reflects prominent themes, such as dualism, which were cornerstone to the Qumran beliefs.

Dualism in the Qumran community is defined by the belief in a divine predetermined plan, which offers two ways of existence. On one end of the spectrum lies goodness and light and on the other, darkness and evil. These sides are in continuous combat, but in the end God will determine ultimate victory to the Sons of Light.[10] Terms used in Visions of Amram, such as Sons of Light and Sons of Darkness, are also reflected throughout Qumran Sectarian literature. The Vision of Amram depicts a scene of two divine figures who claim to rule all humanity. These figures are extensively reflected in significant Qumran literature, such as the Community Rule, where the theme of dualism is prominent.[10]

This extremely fragmentary piece of literature, given its early origins, could have had huge implications on the way dualism developed in Qumran. Unfortunately, due to its thoroughly incomplete nature, most of the insights on dualism gleaned from these documents only find their footing in speculation. For example, 4Q544 has been reconstructed to account a choice of fate offered to Amram, represented by these two figures. In the Qurman community, predeterminism was the common belief which would have led to incongruencies with this text.[10] It is difficult to draw an absolute conclusion on the specific brand of dualism depicted in the Visions of Amram due to its uncertain translation.[3] Nevertheless, it is valuable in providing a more complete look on the traditions and literature that may have inspired and driven the beliefs of the Qumran community.

References

- Stone, Michael E. "Amram." In Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls. : Oxford University Press, 2000. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195084504.001.0001/acref-9780195084504-e-19

- Wise, Michael, Martin Abegg Jr., and Edward Cook. The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 2005.

- Perrin, Andrew B. "Another look at dualism in 4QVISIONS of AMRAM." Henoch 36, no. 1 (2014 2014): 106-117. ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials, EBSCOhost

- Eisenman, Robert, and Michael Wise. "Testament Of Amram." Dead Sea Scrolls Undercovered. 375 Hudson Street: Penguin Books USA Inc., 1993.

- Berthelot, Katell, and Daniel Stokl Ben Ezra. Aramaic Qumranica. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2010. Accessed November 1, 2016.

- Tervanotko, Hannah. Denying Her Voice: The Figure of Miriam in Ancient Jewish Literature. Bristol, CT: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2016. Accessed November 1, 2016.

- Drawnel, Henryk. "The Initial Narrative of the 'Visions of Amram' and its Literary Characteristics". Revue De Qumrân 24, no. 4 (96) (2010): 517-54.

- Drawnel, Henryk. "The Literary Characteristics of the Visions of Levi". Journal for Ancient Judaism, 2010. Accessed November 1, 2016.

- Duke, Robert R. The Social Location of the Visions of Amram (4Q543-547). New York: Peter Lang, 2010.

- Flint, Peter W. The Dead Sea Scrolls. Core Biblical Studies. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2013.