Canadian art

Canadian art refers to the visual (including painting, photography, and printmaking) as well as plastic arts (such as sculpture) originating from the geographical area of contemporary Canada. Art in Canada is marked by thousands of years of habitation by Indigenous peoples followed by waves of immigration which included artists of European origins and subsequently by artists with heritage from countries all around the world. The nature of Canadian art reflects these diverse origins, as artists have taken their traditions and adapted these influences to reflect the reality of their lives in Canada.

| Part of a series on the |

| Canadian art |

|---|

| Collectives |

| Movements |

| Styles |

| Media |

The Government of Canada has played a role in the development of Canadian culture, through the department of Canadian Heritage by giving grants to art galleries,[1] as well as establishing and funding art schools and colleges across the country, and through the Canada Council for the Arts (established in 1957), the national public arts funder, helping artists, art galleries and periodicals, thus contributing to the visual exposure of Canada`s heritage.[2] The Canada Council Art Bank also helps artists by buying and publicizing their work. The Canadian government has sponsored four official war art programs: the First World War Canadian War Memorials Fund (CWMF), the Second World War Canadian War Records (CWR), the Cold War Canadian Armed Forces Civilian Artists Program (CAFCAP), and the current Canadian Forces Artists Program (CFAP).[3]

The Group of Seven is often considered the first uniquely Canadian artistic group and style of painting;[4] however, this claim is challenged by scholars and artists.[5] Historically, the Catholic Church was the primary patron of art in early Canada, especially Quebec, and in later times, artists have combined British, French, and American artistic traditions, at times embracing European styles and at the same time, working to promote nationalism. Canadian art remains the combination of these various influences.

Indigenous art

Indigenous peoples were producing art in the territory that is now called Canada for thousands of years prior to the arrival of European settler colonists and the eventual establishment of Canada as a nation state. Like the peoples that produced them, Indigenous art traditions spanned territories that extended across the current national boundaries between Canada and the United States. Indigenous art traditions are often organized by art historians according to cultural, linguistic or regional groups, the most common regional distinctions being: Northwest Coast, Northwest Plateau, Plains, Eastern Woodlands, Subarctic, and Arctic.[6] As might be expected, art traditions vary enormously amongst and within these diverse groups. One thing that distinguishes Indigenous art from European traditions is a focus on art that tends to be made for "utilitarian, shamanistic or decorative purposes, or for pleasure", as Maria Tippett writes. Such objects might be "venerated or considered ephemeral objects".[7]

Many of the artworks preserved in museum collections date from the period after European contact and show evidence of the creative adoption and adaptation of European trade goods such as metal and glass beads. The distinct Métis cultures that have arisen from inter-cultural relationships with Europeans have also contributed new culturally hybrid art forms. During the 19th and the first half of the 20th century, the Canadian government pursued an active policy of assimilation toward Indigenous peoples. One of the instruments of this policy was the Indian Act, which banned manifestations of traditional religion and governance, such as the Sun Dance and the Potlatch, including the works of art associated with them.[8] It was not until the 1950s and 60s that Indigenous artists such as Mungo Martin,[9] Bill Reid,[10] and Norval Morrisseau[11] began to publicly renew and, in some cases, re-invent indigenous art traditions. Currently there are many Indigenous artists practicing in all media in Canada and two Indigenous artists, such as Edward Poitras[12] and Rebecca Belmore,[13] who have represented Canada at the prestigious Venice Biennale in 1995 and 2005, respectively. Toronto-based Cree artist Kent Monkman is the only Canadian artist to be commissioned by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 2019, he produced the diptych mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) as part of a new series of contemporary projects presented in the Met's Great Hall.[14]

French colonial period (1665–1759)

Early explorers such as Samuel de Champlain made sketches of North American territory as they explored. They also documented conflicts between European colonizers and Indigenous peoples. For instance, a drawing by Champlain, published in 1613, depicts the battle between Champlain's party and the Haudenosaunee that took place in present-day Lake Champlain in 1609.[15]

The Roman Catholic Church in and around Quebec City was the first to provide artistic patronage.[16] Abbé Hughes Pommier is believed to be the first painter in New France. Pommier left France in 1664 and worked in various communities as a priest before taking up painting extensively. Painters in New France, such as Pommier and Claude François (known primarily as Frère Luc, believed in the ideals of High Renaissance art, which featured religious depictions often formally composed with seemingly classical clothing and settings.[17] Few artists during this early period signed their works, making attributions today difficult.

Near the end of the 17th century, the population of New France was growing steadily but the territory was increasingly isolated from France. Fewer artists arrived from Europe, but artists in New France continued with commissions from the Church. Two schools were established in New France to teach the arts and there were a number of artists working throughout New France up until the British Conquest.[18] Pierre Le Ber, from a wealthy Montreal family, is one of the most recognized artists from this period. Believed to be self-taught since he never left New France, Le Ber's work is widely admired. In particular, his depiction of the saint Marguerite Bourgeoys was hailed as "the single most moving image to survive from the French period" by Canadian art historian Dennis Reid.[19]

While early religious painting told little about everyday life, numerous ex-votos completed by amateur artists offered vivid impressions of life in New France. Ex-votos, or votive painting, were made as a way to thank God or the saints for answering a prayer. One of the best known examples of this type of work is Ex-voto des trois naufragés de Lévis (1754). Five youths were crossing the Saint Lawrence River at night when their boat overturned in rough water. Two girls drowned, weighed down by their heavy dresses, while two young men and one woman were able to hold on to the overturned boat until help arrived. Saint Anne is depicted in the sky, saving them. This work was donated to the church at Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré as an offering of thanks for the three lives saved.[20]

Early art in British North America

The early ports of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland did not experience the same degree of artistic growth, largely due to their Protestant beliefs in simple church decoration which did not encourage artists or sculptors. However itinerant artists, painters who travelled to various communities to sell works, frequented the area. Dutch-born artist Gerard Edema is believed to have painted the first Newfoundland landscape in the early 18th century.[21]

British Colonial period (1759–1820)

by Thomas Davies

British Army topographers

The battle for Quebec left numerous British soldiers garrisoned in strategic locations in the territory. While off-duty, many of these soldiers sketched and painted the Canadian land and people, which were often sold in European markets hungry for exotic, picturesque views of the colonies. Many officers in the regiments sent to North America had passed through the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich where watercolour painting was part of the curriculum[22] since watercolours were required by soldiers to record the land, as photography had not been invented.[23] Thomas Davies is championed as one of the most talented. Davies recorded the capture of Louisburg and Montreal among other scenes.[24] Many of Richard Short's drawings and watercolours were reproduced as prints to disseminate knowledge of British expansion. For instance, in 1761, Short’s sketches became the basis for a set of prints depicting the British conquest of Quebec City two years earlier.[25] Scottish-born George Heriot was one of the first artist-soldiers to settle in Canada and later produced Travels Through the Canadas in 1807 filled with his aquatint prints.[26] James Cockburn also was most prolific, creating views of Quebec City and its surroundings.[27] Forshaw Day worked as a draftsman at Her Majesty's Naval Yard from 1862–79 in Halifax, Nova Scotia then moved to Kingston, Ontario to teach drawing at the Royal Military College of Canada from 1879–97.

Lower Canada's Golden Age

In the late 18th century, art in Lower Canada began to prosper due to a larger number of commissions from the public and Church construction. Portrait painting in particular is recognized from this period, as it allowed a higher degree of innovation and change. François Baillairgé was one of the first of this generation of artists. He returned to Montreal in 1781 after studying sculpture in London and Paris. The Rococo style influenced several Lower Canadian artists who aimed for the style's light and carefree painting. However, Baillairgé did not embrace Rococo, instead focusing on sculpture and teaching influenced by Neoclassicism.[28]

Lower Canada's artists evolved independently from France as the connection was severed during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. While not living in Lower Canada, William Berczy participated in the period's artistic growth. He immigrated to North America from Europe, perhaps Saxony, and completed several important portraits of leading figures. For example, he painted three portraits of Kanien’kehá:ka leader Joseph Brant and his best known work, The Woolsley Family, painted in Quebec City in 1808–09. As the title of the latter painting suggests, the work features full-length portraits of all the members of the Woolsley family. It is celebrated in part because of its complex arrangement of figures, decorative floor panels, and the detailed view of the landscape through the open window.[29] Art historian J. Russell Harper believes this era of Canadian art was the first to develop a truly Canadian character.[30]

A second generation of artists continued this flourishing of artistic growth beginning around the 1820s. Joseph Légaré was trained as a decorative and copy painter. However, this did not inhibit his artistic creativity as he was one of the first Canadian artists to depict the local landscape. Légaré is best known for his depictions of disasters such as cholera plagues, rocks slides, and fires.[31] Antoine Plamondon, a student of Légaré, went on to study in France, the first French Canadian artist to do so in 48 years. Plamondon went on to become the most successful artist in this period, largely through religious and portrait commissions.[32]

Krieghoff and Kane

The works of most early Canadian painters were heavily influenced by European trends. During the mid-19th century, Cornelius Krieghoff, a Dutch-born artist in Quebec, painted scenes of the life of the habitants (French-Canadian farmers). At about the same time, the Canadian artist Paul Kane painted pictures of Indigenous life around the Great Lakes, Western Canada and the Oregon Territories. The figure of "the Native" played different roles in art, among others from an "intermediary of the environment" to a model of political resistance".[33] Kane and other Western artists catered to the overseas demand for misleading and stereotypical images of violent Prairie warriors. Kane's dramatic painting The Death of Omoxesisixany (Big Snake) (1849–56) was his only work to be mass-produced and marketed in its own time.[34]

Art under the Dominion of Canada

Formed in 1867 by a group of professional painters, including John Fraser, John Bell-Smith, father of Frederic Marlett Bell-Smith and Adolphe Vogt, the Society of Canadian Artists in Montreal[35] represented the possibilities these artists felt in the city as an exhibiting place for the arts.[36] The group consisted of artists with diverse background, with many new Canadians and others of French heritage spread out over Ontario and Quebec. Without group philosophical or artistic objectives, most artists tended simply to please the public in order to produce income. Romanticism remained the predominant stylistic influence, with a growing appreciation for Realism originating with the Barbizon school as practiced by Canadians Homer Watson and Horatio Walker.[37] The Society however did not last beyond 1872.[38]

In 1872, the Ontario Society of Artists was founded in Toronto; it is still exhibiting today. The list of objectives drawn up by the founding executive in its constitution included the "fostering of Original Art in the province, the holding of Annual Exhibitions, the formation of an Art Library and Museum and School of Art", all goals that were fulfilled.[39][40]

In 1880, the Royal Canadian Academy was founded and it, too, is still active today. It was modelled after the British Royal Academy of Arts with a hierarchy of members, and provided a new national context and vehicle for the promotion of the visual arts.[41]][42] The RCA, under the leadership of Robert Harris, actively sought to place Canadian artists in international exhibitions, such as the Canadian Exhibition at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904.

Early 20th century

The Canadian Art Club, in existence from 1907 to 1915, was formed in an effort to improve the quality of the various standard exhibitions. The founders of the Club were the painters Edmund Morris and Curtis Williamson, who attempted to establish higher standards through small, carefully hung shows. Membership of the Club was by invitation only. Homer Watson was the first president, and other members included William Brymner, Maurice Cullen, and James Wilson Morrice.[43]

The First World War sparked a wide range of artistic expression: photography, film, painting, prints, reproductions, illustration, posters, craft, sculpture, and memorials. Artists initiated some of this work themselves, but the Canadian government and private agencies sponsored the vast majority of it.[44]

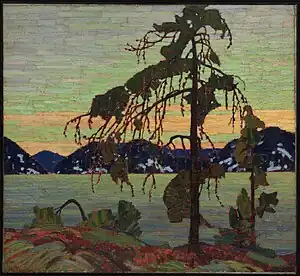

Nationalism and the Group of Seven

.jpg.webp)

The Group of Seven asserted a distinct national identity combined with a common heritage stemming from early modernism in Europe, including Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.[45] Some of the later members worked as commercial artists at a Toronto company called Grip Ltd. where they were encouraged to paint outdoors in their spare time.[46] As mature artists, Influenced by the example of Tom Thomson, they painted works in the studio from sketches made on small panels while on location in Northern Ontario or in the environment closer to home.[47]

The group had its genesis at Toronto's Arts & Letters Club[47] before the First World War, though the war delayed its official formation until 1920. The eventual members were Franklin Carmichael, Lawren Harris, A. Y. Jackson, Frank Johnston, Arthur Lismer, J. E. H. MacDonald, and Frederick Varley. Harris helped, with Dr. James MacCallum, by funding the construction of the Studio building in Toronto in 1913 for some of the group's use as studio space.[47] He also helped fund many of the group's northern excursions beginning 1919 by having a box car outfitted with sleeping quarters and heat, then left at prearranged train track locations to be re-located when the group wanted to move or return.[48] These actions were possible due to Harris' family fortune and influence: his father had been secretary to the A. Harris company which amalgamated with Massey to form the Massey-Harris Company[47] which shipped most of its production by train.

Emily Carr and various other artists were associated with the Group of Seven but were not invited to be members. Tom Thomson, often referred to, but never officially a member, died in 1917 due to an accident on Canoe Lake in Northern Ontario.[49] In 1933, members of the Group of Seven decided to enlarge the group and formed the Canadian Group of Painters, made up of 28 artists from across the country.[50]

Today, particularly with the work of Tom Thomson, the Group of Seven and Emily Carr, Canadian art is reaching new highs in the Canadian auction market.[51] Tom Thomson`s work is especially recognized as a contribution to North American Post-Impressionism[52] and the Group of Seven mythology has become an important part of national identity.[53]

Beginning of non-objective art

In the 1920s, Kathleen Munn, Bertram Brooker and Lowrie Warrener independently experimented with abstract or non-objective art in Canada.[54] Some of these artists viewed abstract art as a way to explore symbolism and mysticism as an integral part of their spirituality. After the Group of Seven was enlarged into the Canadian Group of Painters, in about 1936, Lawren Harris began to paint abstractly. These individual artists indirectly influenced the following generation of artists who would come to form groups of abstract art following World War II, by changing the definition of art in Canadian society and by encouraging young artists to explore abstract themes.[55]

Contemporaries of the Group of Seven

The Beaver Hall Group (1920-1922) in Montreal, a collective of eighteen painters and one sculptor, was founded just after the Group of Seven`s first show. It was named for a building at 305 Beaver Hall which provided a meeting and exhibition space.[56]

By the late 1930s, many Canadian artists began resenting the quasi-national institution the Group of Seven had become. As a result of a growing rejection of the view that the efforts of a group of artists based largely in Ontario constituted a national vision or oeuvre, many artists—notably those in Québec—began feeling ignored and undermined. Founded in 1938 in Montréal, Québec, the Eastern Group of Painters included Montréal artists whose common interest was painting and an art for art's sake aesthetic, not the espousal of a nationalist credo as was the case with the Group of Seven or the Canadian Group of Painters. The group's members included Alexander Bercovitch, Goodridge Roberts, Eric Goldberg, Jack Weldon Humphrey, John Goodwin Lyman, and Jori Smith. The Eastern Group of Painters was formed to restore variation of purpose, method, and geography to Canadian art. It evolved into the Contemporary Arts Society (Société d'art contemporain) which was formed in 1939 by John Goodwin Lyman to promote an awareness of modern art in Montréal.[57]

1930s regionalism

Since the 1930s, Canadian painters have developed a wide range of highly individual styles and painted in different regions of Canada. Emily Carr became famous for her paintings of totem poles, native villages, and the forests of British Columbia. Jack Humphrey painted Saint John, New Brunswick, Carl Schaefer painted Hanover, Ontario, John Lyman painted the Laurentians, and a contingent of artists painted Baie St. Paul in Charlevoix County, Quebec.[58] Later painters who painted specific landscapes include the prairie painter William Kurelek.

After World War II

The abstract painters Jean-Paul Riopelle and multi-media artist Michael Snow can be said to have an influence beyond Canadian borders.[59] Les Automatistes were a group of Québécois artistic dissidents from Montreal, Quebec, founded by Paul-Émile Borduas in the early 1940s.[60][61] It lasted till 1954, the year of the group`s last exhibition.[61] However, their artistic influence was not quickly felt in English Canada, or indeed much beyond Montreal.[62] The abstract art group Painters Eleven (1953-1960), founded in Toronto, particularly the artist William Ronald, who is credited with the group's formation, and Jack Bush, also had an important impact on modern art in Canada. Painters Eleven increased opportunities to exhibit by its members.[63]

Regina Five is the name given to five abstract painters, Kenneth Lochhead, Arthur McKay, Douglas Morton, Ted Godwin, and Ronald Bloore, who exhibited their works in the 1961 National Gallery of Canada's exhibition "Five Painters from Regina". Though not an organized group per se, the name stuck with the 'members' and the artists continued to show together.[64]

Canadian sculpture has been enriched by the walrus ivory and soapstone carvings of Inuit artists. These carvings show objects and activities from their daily lives, both modern and traditional, as well as scenes from their mythology.[65]

Contemporary art

The 1960s saw the emergence of several important local and regional developments in dialogue with international trends. Robert Murray, one of Canada`s foremost abstract sculptors, moved to New York City from Saskatchewan in 1960, and began his progression to International fame.[66]

In Toronto, Spadina Avenue in the 1960s became a hotspot for a loose affiliation of artists, notably Gordon Rayner, Graham Coughtry, and Robert Markle, who came to define the "Toronto look."[67]

Other notable moments when Canadian contemporary artists—as individuals or groups—have distinguished themselves through international recognition or collaborations:

- The interdisciplinary art practice and international success of Michael Snow began in the 1960s.[68]

- Nova Scotia College of Art and Design University (NSCAD). From 1967 to 1990, Garry Neill Kennedy, as President, remade the College into an international centre for artistic activity and invited notable artists to come to NSCAD as visiting artists, particularly those involved in conceptual art.[69] Artists who made significant contributions during this period include Vito Acconci, Sol LeWitt, Dan Graham, Eric Fischl, Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Beuys and Claes Oldenburg.[70] Krzysztof Wodiczko, became an artist-in-residence at NSCAD in 1976 and taught there till 1981. In 1984, he became a Canadian citizen, but went on to increasing fame in New York.[71]

- AA Bronson, Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal under the name of General Idea, active from 1967 to 1994, achieved international success.[72][73]

- The video art and photography of David Askevold, an early and highly influential contributor to the development and pedagogy of the conceptual art movement, occurred. He was invited to NSCAD in 1968.[74] His work is included in the collection of New York's Museum of Modern Art.[75]

- CAR, later CARFAC (in French, Le Front des artistes canadiens) was founded in Ontario by Jack Chambers, with the aid of Tony Urquhart, and Kim Ondaatje in 1968,, ensuring the recognition of artists` copyrights.[76] Due to it, Canada became the first country to pay mandatory exhibition fees to artists.[77] In Moncton, the creation of a fine arts department at the nascent Université de Moncton in 1963[78] was headed by sculptor Claude Roussel, who was representative of CARFAC[79] in New Brunswick and attended the first national conference in Winnipeg of CAR 1971.[80]

- Colin Campbell[81] and Lisa Steele[82] began their pioneering early video art in Toronto in the early 1970s - Steele`s Birthday Suit – with scars and defects (1974) is a classic.

- In Vancouver, Ian Wallace was particularly influential in nurturing an international dialogue through his teaching and exchange programs from 1972 on when he was hired at the Emily Carr University of Art and Design (formerly the Vancouver School of Art). He also encouraged visits from influential figures such as Lucy Lippard and Robert Smithson which exposed younger artists to conceptual art.[83]

- The Vancouver School of Photoconceptualism (including Jeff Wall, Rodney Graham and Stan Douglas) began in the 1980s.[84]

- In 1981, Arnaud Maggs worked on three grid-based portrait works documenting members of Toronto’s art and cultural community: 48 Views, Turning, and Downwind. Together, these works form an extensive visual archive—a kind of who’s who—of the Toronto arts and culture scene in the 1980s.[85]

- The career of Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, who represented Canada at the 49th Venice Biennial in 2001, became internationally successful.[86]

- The films of Mark Lewis, who represented Canada at the Venice Biennale in 2009, have been exhibited in solo museum shows at the Musée du Louvre, Paris (2014), The Power Plant, Toronto (2015), the Art Gallery of Ontario which organized Mark Lewis. Canada (2017),[87] the Museo de Arte de São Paulo (MASP) (2020),[88] and at numerous other international venues. His work has been purchased for public collections world wide.[89]

- The paintings of Steven Shearer, who represented Canada in the Venice Biennale in 2011, are increasingly sought after and shown at international galleries.[90]

- The ceramic figure work of Shary Boyle, who represented Canada in the Venice Biennale in 2013, is increasingly recognized internationally.[91][92]

- Geoffrey Farmer, who represented Canada in the Venice Biennale in 2017, has attracted significant international media attention in international publications contributing to a global conversation about contemporary art in Canada, particularly for his show titled A Way Out of the Mirror.[93]

- In 2019, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art commissioned Kent Monkman to produce the diptych mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) (2019) as part of a new series of contemporary projects presented in its Great Hall. In 2020, The Met acquired the dipytch, which consists of the paintings Welcoming the Newcomers and Resurgence of the People.[94]

Recent achievements of Canadian artists are showcased online at the Canada Council Art Bank site.[95]

See also

- Dance in Canada

- Art of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Beaver Hall Group

- Canadian Group of Painters

- Eastern Group of Painters

- Edmonton Contemporary Artists' Society

- General Idea

- Group of Seven

- Indian Group of Seven

- Les Automatistes

- Les Plasticiens

- List of Canadian artists

- List of Canadian art awards

- List of Canadian painters

- National Gallery of Canada

- Painters Eleven

- Pedimental sculptures in Canada

- Regina Five

- Woodlands School

- Vancouver School

References

- as, for instance, in the following example of a show funded by the Government of Canada at the Peel Art Gallery Museum + Archives, Brampton:"Putting a spotlight on Canada's Artistic Heritage". www.canada.ca. Government of Canada. January 14, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- "Canada Council for the Arts". www.linkedin.com. linked in. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- Brandon, Laura (2021). War Art in Canada: A Critical History. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-4871-0271-5.

- Lynda Jessup (2001). Antimodernism and artistic experience: policing the boundaries of modernity. University of Toronto Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-8020-8354-8.

- The essay collection Sightlines: Reading Contemporary Canadian Art (edited by Jessica Bradley and Lesley Johnstone, Montreal: Artexte Information Centre, 1994) contains a number of critical texts addressing the issues around the difficulty of establishing or even defining a Canadian identity.

- "Exhibitions". Canadian Museum of Civilization. Archived from the original on October 20, 2009. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- Tippett 2017, p. 14.

- Tippett 2017, pp. 75.

- Tippett 2017, pp. 77–78, 129–128, 132–133.

- "Bill Reid", The Canadian Encyclopedia

- Norval Morrisseau. Archived from the original on February 10, 2018. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- Edward Poitras, Encyclopedia of Canada

- Charleyboy, Lisa (March 15, 2014), First Nations artist Rebecca Belmore creates a blanket of beads, CBC News, archived from the original on November 12, 2015, retrieved March 23, 2021

- Madill, Shirley (2022). Kent Monkman: Life & Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-4871-0280-7.

- Brandon, Laura (2021). War Art in Canada: A Critical History. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-4871-0271-5.

- Harper, 3.

- Harper, 4-5.

- Harper, 19–20.

- Reid, 10.

- Harper, 14-15.

- Harper, 27–28.

- "Adamson, p.5."

- Reid, 15.

- Reid, 16.

- Brandon, Laura (2021). War Art in Canada: A Critical History. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-4871-0271-5.

- Reid, 19.

- "Adamson, p.5"

- Harper, 56-62.

- Reid, 28.

- Harper, 67.

- Reid, 42.

- Reid, 42.

- Vigneault, Louise (2015). "Portraying Indigenous Peoples in Nineteenth-Century Art: Conciliatory, Resistant, Immutable". Embracing Canada: Landscapes from Krieghoff to the Group of Seven. Ian M. Thom (ed.). Vancouver and London, Eng.: Vancouver Art Gallery and Black Dog Publishing. pp. 17–23. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- Brandon, Laura (2021). War Art in Canada: A Critical History. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-4871-0271-5.

- "Adamson, p.12

- Reid, 80.

- Harper, 179–81.

- "Adamson, p.12

- Murray 1972, p. 5.

- "The Founding of the Society and its First Exhibition". Archives of Ontario. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- "Adamson, p.14

- Records of the Founding of the Royal Canadian Academy of the Arts. Toronto: Globe Printing Co. 1879–80. ISBN 9780665132964.

- "Canadian Art Club". www.oxfordreference.com. Oxford Reference. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- Brandon, Laura (2021). War Art in Canada: A Critical History. Toronto: Art Canada Institute.

- Murray 1999, p. 32.

- Murray & Harris 1993, p. 8.

- Murray & Harris 1993, p. 9.

- Murray & Harris 1993, p. 11.

- Murray 1999, p. 22ff.

- Murray 1999, p. 78.

- Dixon, Guy (December 19, 2017). "Canadian Art Reaching New Summits". The Globe and Mail. Globe and Mail, Dec 19, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- Murray, Joan. ""Tom Thomson". The Advent of Modernism : Post-Impressionism and North American Art 1900–1918". Peter Morrin; William C. Agee; Judith Zilczer. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- Edwardson, Ryan (2004). "A Canadian Modernism: The Pre-Group of Seven 'Algonquin School', 1912–17". British Journal of Canadian Studies. 17 (1): 81–92. doi:10.3828/bjcs.17.1.6. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- Murray 1999, p. 38ff.

- Nasgaard, 14.

- Murray 1999, p. 34ff.

- Murray 1999, p. 80.

- Murray 1999, p. 63.

- Murray 1999, p. 93, 140.

- Nasgaard, Roald (2009). "The Automatiste Revolution in Painting". The Automatist Revolution. Roald Nasgaard and Ray Ellenwood. Vancouver, BC: D&M Publishers Inc. p. 7.

- Murray 1999, p. 96.

- Norwell, Iris. (2011), Painters Eleven:The Wild Ones of Canadian Art, Publishers Group West, ISBN 978-1-55365-590-9

- Murray 1999, p. 101.

- Terry Fenton, "ECAS And What It Stands For", ECAS 15th Annual Exhibition catalogue essay

- Tippett 2017, pp. 71–73, 126–128, 227–229.

- Boyanoski, Christine (2010). "Sculpture before 1960". The Visual Arts in Canada: the Twentieth Century. Foss, Brian., Paikowsky, Sandra., Whitelaw, Anne (eds.). Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-19-542125-5. OCLC 432401392.

- Peter Goddard, "Remembering Toronto's 1960s Spadina Art Scene" Archived 2015-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, Canadian Art, July 11, 2014

- Murray 1999, p. 140.

- "Garry Neill Kennedy". www.gallery.ca. National Gallery of Canada. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- Stacey, Robert; Wylie, Liz (1988). Eighty/Twenty: 100 Years at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. Halifax: Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. p. 78-80. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- "Krzysztof Wodiczko". art21.org. Art21. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- Murray 1999, p. 176.

- "General Idea". www.tate.org. Tate Gallery, London, UK. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- "David Askevoid". www.gallery.ca. National Gallery of Canada. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- "David Askevold". www.moma.org. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- Poole, Nancy Geddes. "The Art of London: 1830-1980". ir.lib.uwo.ca. McIntosh Gallery, London, Ontario. p. 210. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- Cheetham, Mark A. "Jack Chambers: Significance & critical issues". www.aci-iac.ca. Art Canada Institute. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- "Claude Roussel". www.moncton.ca. Order of Moncton. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- "CARFAC members". www.carfac.ca. CARFAC. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- "Artist Attends Conference". Moncton Transcript, October 9, 1971, National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Artist`s file

- Murray 1999, p. 177.

- Murray 1999, p. 177ff.

- Harris, Michael. "Artist Ian Wallace". Nuovomagazine.com. Nuvo magazine, spring 1913. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- Murray 1999, p. 208-209.

- Cibola, Anne (2022). Arnaud Maggs: Life & Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-4871-0276-0.

- Wray, John (July 26, 2012). "Janet Cardiff, George Bures Miller and the Power of Sound". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- "Mark Lewis. Canada". ago.ca. Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- "Mark Lewis". www.youtube.com. OCAD, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- Lewis, Mark. "Mark Lewis". www.gallery.ca. National Gallery of Canada. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- "Steven Shearer". capturephotofest.com. Capture. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- Smith, Andy (September 14, 2019). "The Ceramic Figures of Shary Boyle". hifructose.com. Hi-Fructose, Sept 14, 2019.

- "Venice Biennale". National Gallery of Canada. Archived from the original on October 13, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- "Canada - Geoffrey Farmer - A Way Out Of The Mirror - Venice Biennale 2017". www.youtube.com. National Gallery of Canada. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- Madill, Shirley (2022). Kent Monkman: Life & Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-4871-0280-7.

- "Artist Spotlight". artbank.ca. Canada Council Art Bank. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

Further reading

- Adamson, Jeremy (1978). From Ocean to Ocean: Nineteenth Century Water Colour Painting in Canada. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario. ISBN 9780919876255. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- Auger, Emily Elisabeth (2005), The way of Inuit art: aesthetics and history in and beyond the Arctic, McFarland, ISBN 0-7864-1888-5

- Brandon, Laura (2021). War Art in Canada: A Critical History. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-4871-0271-5.

- Bryce, Alan D (2007), Art smart : the intelligent guide to investing in the Canadian art market, Dundurn Group, ISBN 9781550026764

- Bradley, Jessica and Lesley Johnstone. (1994) Sightlines: Reading Contemporary Canadian Art. Montreal: Artexte Information Centre, . ISBN 2-9800632-9-0

- Crandall, Richard C (2000), Inuit art: a history, McFarland, ISBN 0-7864-0711-5

- Gérin, Annie; McLean, James S. (2009), Public art in Canada: critical perspectives, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-9847-4

- Harper, Russell. (1981) Painting in Canada: A History 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-6307-1

- Jonaitis, Aldona (2006), Art of the Northwest coast, University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-1-55365-210-6

- Murray, Joan (1999). Canadian Art in the Twentieth Century. Toronto: Dundurn. OCLC 260193722. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- Murray, Joan; Harris, Lawren (1993), The Best of the Group of Seven, McClelland & Stewart, ISBN 0-7710-6674-0

- Murray, Joan (1972). Ontario Society of Artists: 100 Years. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario.

- Nasgaard, Roald (2008). Abstract Painting in Canada. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 9781553653943. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- Nowell, Iris. (2011), Painters Eleven:The Wild Ones of Canadian Art, Publishers Group West, ISBN 978-1-55365-590-9

- Pearse, Harold (2006), From drawing to visual culture: a history of art education in Canada, McGill-Queen's University Press, ISBN 0-7735-3070-3

- Robertson, Clive (2006), Policy Matters: Administrations of Art and Culture, YYZ Books, ISBN 0-920397-36-0

- Reid, Dennis (2012). A Concise History of Canadian Painting (Third ed.). Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- Tippett, Maria (2017). Sculpture in Canada. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978-1-771-62094-9. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- Tippett, Maria (1993). By a Lady: Celebrating Three Centuries of Art by Canadian Women. Toronto: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-016955-5.

- Walters, Evelyn (2005), The women of Beaver Hall: Canadian modernist painters, Dundurn Press, ISBN 1-55002-588-0

- Whitelaw, Anne; Foss, Brian; Paikowsky, Sandra, eds. (2010). The Visual Arts in Canada: The Twentieth Century. Canada: Oxford. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

External links

Media related to Art of Canada at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Art of Canada at Wikimedia Commons- Artists in Canada A CHIN (Canadian Heritage Information Network) Resource