Prana

In yoga, Ayurveda, and Indian martial arts, prana (प्राण, prāṇa; the Sanskrit word for breath, "life force", or "vital principle")[1] permeates reality on all levels including inanimate objects.[2] In Hindu literature, prāṇa is sometimes described as originating from the Sun and connecting the elements.[3]

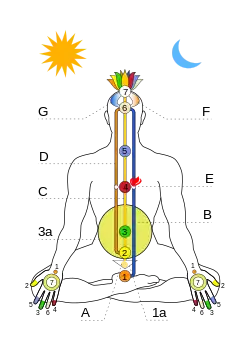

Five types of prāṇa, collectively known as the five vāyus ("winds"), are described in Hindu texts. Ayurveda, tantra and Tibetan medicine all describe prāṇa vāyu as the basic vāyu from which the other vāyus arise.

Prana is divided into ten main functions: The five Pranas – Prana, Apana, Udana, Vyana and Samana – and the five Upa-Pranas – Naga, Kurma, Devadatta, Krikala and Dhananjaya.

Pranayama, one of the eight limbs of yoga, is intended to expand prana.

Etymology

V. S. Apte provides fourteen different meanings for the Sanskrit word prāṇa (प्राण) including breath or respiration;[4] the breath of life, vital air, principle of life (usually plural in this sense, there being five such vital airs generally assumed, but three, six, seven, nine, and even ten are also spoken of);[4][5] energy or vigour;[4] the spirit or soul.[4]

Of these meanings, the concept of "vital air" is used by Bhattacharyya to describe the concept as used in Sanskrit texts dealing with pranayama, the manipulation of the breath.[6] Thomas McEvilley translates prāṇa as "spirit-energy".[7] The breath is understood to be its most subtle material form, but is also believed to be present in the blood, and most concentrated in semen and vaginal fluid.[8]

Early references

The ancient concept of prāṇa is described in many Hindu texts, including Upanishads and Vedas. One of the earliest references to prāṇa is from the 3,000-year-old Chandogya Upanishad, but many other Upanishads use the concept, including the Katha, Mundaka and Prasna Upanishads. The concept is elaborated upon in great detail in the literature of haṭha yoga,[9] tantra, and Ayurveda.

The Bhagavad Gita 4.27 describes the yoga of self-control as the sacrifice of the actions of the senses and of prāṇa in the fire kindled by knowledge.[10] More generally, the conquest of the senses, the mind, and prāṇa is seen as an essential step on the yogin's path to samadhi, or indeed as the goal of yoga.[11] Thus for example the Malinivijayottaratantra 12.5–7 directs the seeker "who has conquered posture, the mind, prāṇa, the senses, sleep, anger, fear, and anxiety"[12] to practise yoga in a beautiful undisturbed cave.[12]

Prāṇa is typically divided into constituent parts, particularly when concerned with the human body. While not all early sources agree on the names or number of these divisions, the most common list from the Mahabharata, the Upanishads, Ayurvedic and Yogic sources includes five classifications, often subdivided.[13] This list includes prāṇa (inward moving energy), apāna (outward moving energy), vyāna (circulation of energy), udāna (energy of the head and throat), and samāna (digestion and assimilation).

Early mention of specific prāṇas often emphasized prāṇa, apāna and vyāna as "the three breaths". This can be seen in the proto-yogic traditions of the Vratyas among others.[14] Texts like the Vaikānasasmārta utilized the five prāṇas as an internalization of the five sacrificial fires of a panchāgni homa ceremony.[15]

The Atharva Veda describes prāṇa: 'When they had been watered by Prana, the plants spake in concert: 'thou hast, forsooth, prolonged our life, thou hast made us all fragrant.' (11.4–6) 'The holy (âtharvana) plants, the magic (ângirasa) plants, the divine plants, and those produced by men, spring forth, when thou, O Prâna, quickenest them (11.4–16). 'When Prâna has watered the great earth with rain, then the plants spring forth, and also every sort of herb.' (11.4–17) 'O Prâna, be not turned away from me, thou shall not be other than myself! As the embryo of the waters (fire), thee, O Prâna, do bind to me, that I may live.' (11.4)

Similar concepts

Similar concepts exist in various cultures, including the Latin anima ("breath", "vital force", "animating principle"), Islamic and Sufic ruh, the Greek pneuma, the Chinese qi, the Polynesian mana, the Amerindian orenda, the German od, and the Hebrew ruah.[16] Prāṇa is also described as subtle energy[17] or life force.[18]

Vāyus

One way of categorizing prāṇa is by means of vāyus. Vāyu means "wind" or "air" in Sanskrit, and the term is used in a variety of contexts in Hindu philosophy. Prāṇa is considered the basic vāyu from which the other vāyus arise, as well as one of the five major vāyus. Prāṇa is thus the generic name for all the breaths, including the five major vāyus of prāṇa, apāna, uḍāna, samāna, and vyāna.[19] The Nisvasattvasamhita Nayasutra describes five minor winds, naming three of these as nāga, dhanamjaya, and kurma;[20] the other two are named in the Skandapurana (181.46) and Sivapurana Vayaviyasamhita (37.36) as devadatta and krtaka.[21]

| Vāyu | Location | Responsibility[22] |

|---|---|---|

| Prāṇa | Head, lungs, heart | Movement is inward and upward, it is the vital life force. Balanced prāṇa leads to a balanced and calm mind and emotions. |

| Apāna | Lower abdomen | Movement is outward and downward, it is related to processes of elimination, reproduction and skeletal health (absorption of nutrients). Balanced apāna leads to a healthy digestive and reproductive system. |

| Udāna | Diaphragm, throat | Movement is upward, it is related to the respiratory functions, speech and functioning of the brain. Balanced udāna leads to a healthy respiratory system, clarity of speech, healthy mind, good memory, creativity, etc. |

| Samāna | Navel | Movement is spiral, concentrated around the navel, like a churning motion, it is related to digestion on all levels. Balanced samāna leads to a healthy metabolism. |

| Vyāna | Originating from the heart, distributed throughout | Movement is outward, like the circulatory process. It is related to circulatory system, nervous system and cardiac system. Balanced vyāna leads to a healthy heart, circulation and balanced nerves. |

Nadis

Indian philosophy describes prana flowing in nadis (channels), though the details vary.[23] The Brhadaranyaka Upanishad (2.I.19) mentions 72,000 nadis in the human body, running out from the heart, whereas the Katha Upanishad (6.16) says that 101 channels radiate from the heart.[23] The Vinashikhatantra (140–146) explains the most common model, namely that the three most important nadis are the Ida on the left, the Pingala on the right, and the Sushumna in the centre connecting the base chakra to the crown chakra, enabling prana to flow throughout the subtle body.[23]

When the mind is agitated due to our interactions with the world at large, the physical body also follows in its wake. These agitations cause violent fluctuations in the flow of prana in the nadis.[24]

Pranayama

Prāṇāyāma is a common term for various techniques for accumulating, expanding and working with prana. Pranayama is one of the eight limbs of yoga and is a practice of specific and often intricate breath control techniques. The dynamics and laws of Prana were understood through systematic practice of Pranayama to gain mastery over Prana.[25]

Many pranayama techniques are designed to cleanse the nadis, allowing for greater movement of prana. Other techniques may be utilized to arrest the breath for samadhi or to bring awareness to specific areas in the practitioner's subtle or physical body. In Tibetan Buddhism, it is utilized to generate inner heat in the practice of tummo.[26][27]

In Ayurveda and therapeutic yoga, pranayama is utilized for many tasks, including to affect mood and aid in digestion. A. G. Mohan stated that the physical goals of pranayama may be to recover from illness or the maintenance of health, while its mental goals are: "to remove mental disturbances and make the mind focused for meditation".[28]

According to the scholar-practitioner of yoga Theos Bernard, the ultimate aim of pranayama is the suspension of breathing, "causing the mind to swoon".[29] Swami Yogananda writes, "The real meaning of Pranayama, according to Patanjali, the founder of Yoga philosophy, is the gradual cessation of breathing, the discontinuance of inhalation and exhalation".[30]

References

- "Prana". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2015-04-22.

- Rama, Swami (2002). Sacred journey: living purposefully and dying gracefully. India: Himalayan Institute Hospital Trust. ISBN 978-8188157006. OCLC 61240413.

- Swami Satyananda Saraswati (September 1981). "Prana: the Universal Life Force". Yoga Magazine. Bihar School of Yoga. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965), The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary (4th ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, p. 679, ISBN 81-208-0567-4

- For the vital airs as generally assumed to be five, with other numbers given, see: Macdonell, p. 185.

- Bhattacharyya, p. 311.

- McEvilley, Thomas. "The Spinal Serpent", in: Harper and Brown, p. 94.

- Richard King, Indian philosophy: an introduction to Hindu and Buddhist thought. Edinburgh University Press, 1999, p. 70.

- Mallinson, James (2007). The Shiva Samhita: A Critical Edition and an English Translation (1st ed.). Woodstock, New York: YogaVidya.com. ISBN 978-0971646650.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 25.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 47.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 60.

- Sivananda, Sri Swami (2008). The Science of Pranayama. BN Publishing. ISBN 978-9650060206.

- Eliade, Trask & White 2009, p. 104.

- Eliade, Trask & White 2009, pp. 111–112.

- Feuerstein, George (2013) [1998]. The Yoga Tradition: Its History, Literature, Philosophy and Practice. Hohm Press. ISBN 978-1935387589.

- Srinivasan, TM (2017). "Biophotons as subtle energy carriers". International Journal of Yoga. 10 (2): 57–58. doi:10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_18_17. PMC 5433113. PMID 28546674.

- Rowold, Jens (August 2016). "Validity of the Biofield Assessment Form (BAF)". European Journal of Integrative Medicine. 8 (4): 446–452. doi:10.1016/j.eujim.2016.02.007.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 128, 173–174, 191–192.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 191–192.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 174.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 191.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 172–173.

- Sridhar, M. K. (2015). "The concept of Jnana, Vijnana and Prajnana according to Vedanta philosophy". International Journal of Yoga: Philosophy, Psychology and Parapsychology. 3 (1): 5. doi:10.4103/2347-5633.161024. S2CID 147000303.

- Nagendra, H. R. (1998). Pranayama, The art and science. Bangalore, India: Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashana.

- Ra Yeshe Senge (2015). The All-Pervading Melodious Drumbeat: The Life of Ra Lotsawa. Penguin. pp. 242 see entry for Tummo. ISBN 978-0-698-19216-4.

- Dharmakirti (2002). Mahayana tantra: an introduction. Penguin Books. pp. 126–127. ISBN 9780143028536.

- Mohan, A. G.; Mohan, Indra (2004). Yoga Therapy: A Guide to the Therapeutic Use of Yoga and Ayurveda for Health and Fitness (1st ed.). Boston: Shambhala Publications. p. 135. ISBN 978-1590301319.

- Bernard, Theos (2007). Hatha Yoga: The Report of A Personal Experience. Harmony. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-9552412-2-2. OCLC 230987898.

- Yogananda, Paramahansa (2005). The Essence of Kriya Yoga (1st ed.). Alight Publications. p. part10 (online). ISBN 978-1931833189.

Sources

- Eliade, Mircea; Trask, Willard R.; White, David Gordon (2009). Yoga: Immortality and Freedom. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691142036.

- Mallinson, James; Singleton, Mark (2017). Roots of Yoga. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-25304-5. OCLC 928480104.

- Gyatso, Kelsang. Clear Light of Bliss.