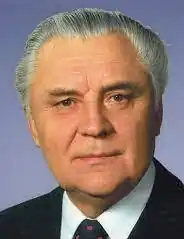

Volodymyr Shcherbytsky

Volodymyr Vasylyovych Shcherbytsky[lower-alpha 1] (17 February 1918 – 16 February 1990[1]) was a Ukrainian Soviet politician. He was First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic from 1972 to 1989.[1]

Volodymyr Shcherbytsky | |

|---|---|

| Володи́мир Щерби́цький | |

| |

| First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine | |

| In office 25 May 1972 – 28 September 1989 | |

| Preceded by | Petro Shelest |

| Succeeded by | Vladimir Ivashko |

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic | |

| In office 23 October 1965 – 25 May 1972 | |

| Preceded by | Ivan Kazanets |

| Succeeded by | Oleksandr Liashko |

| In office 28 February 1961 – 26 June 1963 | |

| Preceded by | Nikifor Kalchenko |

| Succeeded by | Ivan Kazanets |

| First Secretary of the Dnipropetrovsk Regional Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine | |

| In office 7 July 1963 – 23 October 1965 | |

| Preceded by | Nikita Tolubeev |

| Succeeded by | Oleksiy Vatchenko |

| In office December 1955 – December 1957 | |

| Preceded by | Andrei Kirilenko |

| Succeeded by | Anton Gayevoy |

| Full member of the 24th , 25th, 26th, 27th Politburo | |

| In office 9 April 1971 – 20 September 1989 | |

| Candidate member of the 22nd Politburo | |

| In office 6 December 1965 – 8 April 1966 | |

| In office 31 October 1961 – 13 December 1963 | |

| Full member of the 22nd, 23rd, 24th, 25th, 26th, 27th Central Committee | |

| In office 31 October 1961 – 16 February 1990 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 17 February 1918 Verkhnodniprovsk, Yekaterinoslav Governorate, Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets, Russian SFSR[1] (now Ukraine) |

| Died | 16 February 1990 (aged 71) Kyiv, Ukrainian SSR, Soviet Union |

| Resting place | Baikove Cemetery, Kyiv |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1948–1989) |

| Signature | |

Early life

Shcherbytsky was born in Verkhnodniprovsk on 17 February 1918 to Vasily Grigorievich Shcherbytsky (1890-1949) and Tatyana Ivanovna Shcherbitskaya (1898-1990), just two weeks after the Soviet takeover of the city during the Ukrainian–Soviet War. During his school years, he worked as an activist and a member of the Komsomol from 1931. In 1934, while still in school, he became an instructor and agitator for the district committee of the Komsomol. In 1936, he entered the Faculty of Mechanics at the Dnipropetrovsk Chemical Technology Institute. During his training, he worked as a draftsman, designer and compressor driver at the factories in Dnepropetrovsk. Shcherbytsky graduated from the Dnipropetrovsk Chemical Technology Institute in 1941 and in the same year became a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[1]

Military career

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Shcherbytsky was mobilized into the ranks of the Red Army. Because he was a graduate with a major in chemical equipment and machinery, he was sent to attend short term courses at the Military Academy of Chemical Protection named after Voroshilov, which was evacuated from Moscow to Samarkand in Uzbek SSR. After graduation, Shcherbytsky was appointed head of the chemical unit within the 34th Infantry Regiment of the 473rd Infantry Division in the Transcaucasian Front. In November 1941, the division was formed in the cities of Baku and Sumgayit in Azerbaijan SSR. On 8 January 1942, the division was renamed as 75th Rifle Division, and in April of the same year, Shcherbytsky and the division took part in the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. On the same year, he served in a tank brigade.[2][3]

In March 1943, Shcherbytsky was transferred to the chemical department at the headquarters of the Transcaucasian Front, where he served until the end of the war. In August 1945, the Transcaucasian Front was reorganized into the Tbilisi Military District and Shcherbytsky's last military assignment was as an assistant chief of the chemistry department of the district headquarters for combat training. In December 1945, he left the military service at the rank of captain.[2][3]

Political career

After World War II, he worked as an engineer in Dniprodzerzhynsk (now Kamianske).[1] From 1948 Shcherbytsky was a party functionary in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[1] In 1948, he was appointed Second Secretary of Dniprodzerhynsk city communist party committee, soon after Leonid Brezhnev had taken over the First Secretary of the regional party committee. He succeeded Brezhnev as regional party boss in November 1955. In December 1957, he was appointed a Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. In February 1961, he was appointed chairman of the Ukrainian Council of Ministers, the second highest post in the republic, but in June 1963, just after Petro Shelest had been appointed First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Shcherbytysky was shifted to the lesser job of First Secretary of the Dnipropetrovsk regional party committee.[4] On October 16, 1965, after Brezhnev had risen to the supreme position as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Shcherbytsky was restored to his former position at the head of the Ukrainian government.

In May 1972, Shelest was recalled from his post as head of the Ukrainian government. He was instead transferred to Moscow and elected to be the Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR. As a result of this spontaneous political development, the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Communist Party elected Shcherbytysky as their new First Secretary; this was the highest political office in the Ukrainian SSR. While his predecessor had maintained a degree of independence from Moscow and had given limited encouragement to native Ukrainian culture, Shcherbytsky was unfailingly loyal to Brezhnev, and conducted policy accordingly. In total, around 37,000 party members and government officials who had been appointed by Shelest were purged - removed from their posts or transferred to less influential political positions. They were accused of softness towards Ukrainian nationalism - suppressing nationalism was a policy historically conducted by the USSR in order to maintain peace between the over 50 ethnicities within the country's borders. Most famously, a well-known Ukrainian writer, Ivan Dziuba, was sentenced to five years in a labour camp for a publication that was deemed as threatening to the friendship between the Soviet people.[5]

Russification

His rule of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was characterized by the expanded policies of re-centralisation and suppression of dissent accompanied by a broad assault on Ukrainian culture and intensification of Russification.[6][7] During Shcherbytsky's rule mass arrests were carried out that incarcerated any member of the intelligentsia that dared to dissent from official state policies.[8] The expirations of political prisoners’ sentences were increasingly followed by re-arrest and new sentences on charges of criminal activity.[7] Incarceration in psychiatric institutions became a new method of political repression.[7] Ukrainian language press, scholarly and cultural organisations which had flourished under Shcherbytsky's predecessor Shelest were repressed by Shcherbytsky.[6] Shcherbytsky also made a point of speaking Russian at official functions while Shelest spoke Ukrainian in public events.[9] In an October 1973 speech to fellow party members Shcherbytsky stated that as an "internationalist" Ukrainians were meant to "express feelings of friendship and brotherhood to all people of our country but first of all against the great Russian people, their culture, their language - the language of the Revolution, of Lenin, the language of international intercourse and unity".[10] Shcherbytsky also claimed that "the worst enemy of the Ukrainian people" is "Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism and also international Zionism".[10] During Shcherbytsky's rule, Ukrainian-language education was greatly scaled back.[10]

Other aspects of his rule and downfall

Shcherbytsky was an influential figure in the Soviet Union. In April 1971, he was promoted to membership of the Politburo, on which he remained a close ally of Leonid Brezhnev.[9][1] His power base was arguably one of the most corrupt and conservative among the Soviet republics.[11]

From 1972 to 1989, the economy of Ukraine continued to decline.[6]

In 1982, there was a rumour in the Kremlin that Brezhnev, whose health was failing, planned to relinquish the post of General Secretary of the Communist Party at the forthcoming Central Committee plenum and hand over to Shcherbytsky, but when Brezhnev died unexpectedly, his place was taken by Yuri Andropov.

After Andropov and his successor Konstantin Chernenko died and were succeeded by the reformist Mikhail Gorbachev, who wanted to immediately dismiss Shcherbytsky due to his hardline rule. However, he decided to allow him to remain in office for several more years in order to keep the Ukrainian nationalist movement subdued.[12]

Chernobyl disaster

After the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, Shcherbytsky was ordered by General Secretary Gorbachev to go ahead with the usual International Workers' Day parade on the Khreshchatyk in Kyiv on May Day, to show people that there was no reason for panic. He went ahead with this plan in order, knowing that there was danger of spreading radiation sickness, even taking his own grandson Volodya to the celebrations.[13] But he arrived late, and complained to aides: "He told me: 'You will put your party card on the table if you bungle the parade'."[14]

On 20 September 1989, Shcherbytsky lost his membership of the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in a purge of conservative members pushed through by Gorbachev.[15] Eight days later he was removed from leadership of the Communist Party of Ukraine at a plenum in Kyiv personally presided over by Gorbachev.[16]

Death and legacy

Shcherbytsky died on 16 February 1990[17] - one day before his 72nd birthday, which also when he was supposed to testify in the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR about the events related to the Chernobyl disaster. Although the official version claims that the cause of death was pneumonia, it was alleged that he had committed suicide by shooting himself with his carbine, "unable to deal not only with the end of his own career but also with the end of the political and social order he had served all his life" and had left a suicide note explaining to his wife how to deal with the money in his savings account.[18][19] He was buried at the Baikove Cemetery in Kyiv.

A street named after Shcherbytsky in Kamianske was renamed to Viacheslav Chornovil Street in 2016 due to Ukrainian decommunization laws.[20] In the same year, a street named after him in Dnipro (formerly Dnipropetrovsk) was renamed to Olena Blavatsky Street.[21]

Personal life

Shcherbytsky was married to Ariadna Gavrilovna Shcherbitskaya, née Zheromskaya (1923–2015) on 13 November 1945. The couple had two children; son Valery (1946-1991), who died due to alcohol and drug addiction just one year after Shcherbytsky's death, and a daughter Olga (1953-2014), who died at a hospital in Kyiv after a serious and prolonged illness. He also had numerous grand and great-grandchildren. Olga was married to Bulgarian businessman Borislav Dionisiev, who then was a soldier in the Bulgarian People's Army and a Consul General of Bulgaria in Odesa, before divorcing in an unknown date.[22][23][24][25]

Awards

Volodymyr Shcherbytsky was twice awarded the Hero of Socialist Labour — in 1974 and 1977. During his public service he also received numerous other civil and state awards and recognitions, including the Order of Lenin (in 1958, 1968, 1971, 1973, 1977, 1983 and 1988), the Order of October Revolution (in 1978 and 1982), the Order of the Patriotic War, I class (in 1985), the Medal "For the Defence of the Caucasus" (in 1944) and various medals. He was also awarded the Order of Victorious February by the Government of Czechoslovakia (in 1978).[26]

Quotes

In 1985 Leonid Kravchuk, secretary of Communist Party of Ukraine regarding ideological matters, was preparing a report for Shcherbytsky for the next party committee gatherings following a plenum of the Central Committee of Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In this report Kravchuk mentioned the word perestroika. As soon as Shcherbytsky had heard the word, he stopped Kravchuk and asked:

What fool (durak) invented this word perestroika? Why rebuild the house? Is there anything wrong in the Soviet Union? We are fine! What is there to rebuild? It is necessary to improve, reorganize, but why, if the house is not falling apart, why does it need to be rebuilt?

Notes

References

- Shcherbytsky, Volodymyr, Encyclopedia of Ukraine (accessed on 6 February 2021)

- "ВЛАДИМИР ЩЕРБИЦКИЙ И ЕГО ВРЕМЯ". liva.com.ua. 13 February 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Щербацкий Владимир Васильевич". warheroes.ru. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Tatu, Michel (1969). Power in the Kremlin. London: Collins. pp. 513–14.

- "Ukrainian dissident Dziuba from Donbas, first analyst of Russification". 10 January 2023. Archived from the original on 10 January 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- Bernard A. Cook (8 February 2001). Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 1280. ISBN 978-1-135-17932-8.

- Ukraine under Shcherbytsky, Encyclopædia Britannica (accessed on 6 February 2021)

- Christopher A. Hartwell (26 September 2016). Two Roads Diverge: The Transition Experience of Poland and Ukraine. Cambridge University Press. p. 263. ISBN 978-1107530980.

- Subtelny, Orest (10 November 2009). Ukraine: A History, 4th Edition. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442697287.

- Bohdan Nahaylo, The Ukrainian Resurgence, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1999, pages 39 and 40

- Democratic Changes and Authoritarian Reactions in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova By Karen Dawisha, Bruce Parrott. Cambridge University Press, 1997 ISBN 0-521-59732-3, ISBN 978-0-521-59732-6. p. 337

- Marples, David R. (2004). The Collapse of the Soviet Union: 1985-1991 (1 ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson. p. 35. hdl:2027/mdp.39015059113335. ISBN 1-4058-9857-7. OCLC 607381176.

- "Горбачев - Щербицкому: Не проведешь парад - сгною!".

- Plokhy, Serhii (2016). The Gates of Europe, A History of Ukraine. London: Penguin. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-141-98061-4.

- Garthoff, Raymond L. (1994). The Great Transition: American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution. p. 393. ISBN 0-8157-3060-8.

- Garthoff, Raymond L. (1994). The Great Transition: American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution. p. 397. ISBN 0-8157-3060-8.

- "Vladimir Shcherbitsky, 71, Dies; Former Ukraine Communist Chief". The New York Times. Associated Press. 18 February 1990.

- Plokhy. The Gates of Europe. p. 315.

- "На чолі УРСР: "націоналіст" Шелест і "москвофіл" Щербицький". fpp.com.ua. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Какие улицы сменили название в Днепродзержинске [Which streets have changed their name in Dneprodzerzhinsk]. Sobitie (in Russian). 19 February 2016. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- Історія самої незвичайної вулиці Дніпропетровська [The history of the most unusual street in Dnepropetrovsk]. New Dnipro (in Ukrainian). 4 October 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- "Непутевые дети знаменитых людей". kp.ua. 18 March 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- "Владимир Щербицкий познакомился с женой на войне". kp.ua. 17 February 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- "Вдова Щербицкого в единственном интервью: После смерти мужа пришлось выселиться из ведомственной квартиры, у нас нет даже элементарной машины". gordonua.com. 11 November 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- "Borislav Dionisiev left a BGN 300 million legacy! The money goes to …". darik.news. 11 September 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- "ЩЕРБИЦЬКИЙ Володимир Васильович". kmu.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ""Щербицкий сказал - какой дурак придумал слово перестройка?.."".

- "Владимир Щербицкий: последний украинский секретарь". Archived from the original on 21 April 2018.

External links

- Shcherbytsky Volodymyr Vasylyovych, from the Ukrainian Government Portal

- Nikitin, A. Vladimir Scherbitskiy: the last Ukrainian secretary (Владимир Щербицкий: последний украинский секретарь). Vzglyad. 6 December 2013

- Latysh Yu. Vladimir Shcherbitsky and his time