Volcanism of New Zealand

The volcanism of New Zealand has been responsible for many of the country's geographical features, especially in the North Island and the country's outlying islands.

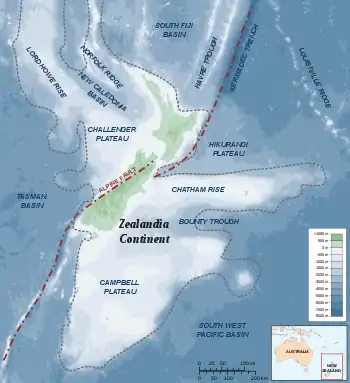

While the land's volcanism dates back to before the Zealandia microcontinent rifted away from Gondwana 60–130 million years ago, activity continues today with minor eruptions occurring every few years. This recent activity is primarily due to the country's position on the boundary between the Indo-Australian and Pacific Plates, a part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, and particularly the subduction of the Pacific Plate under the Indo-Australian Plate.

New Zealand's rocks record examples of almost every kind of volcanism observed on Earth, including some of the world's largest eruptions in geologically recent times.

None of the South Island's volcanoes are active.

Major eruptions

New Zealand has been the site of many large explosive eruptions during the last two million years, including several of supervolcano size.[1] These include eruptions from Macauley Island and the Taupō, Whakamaru, Mangakino, Reporoa, Rotorua, and Haroharo calderas.

Two relatively recent eruptions from the Taupō Volcano are perhaps the best known. Its Oruanui eruption was the world's largest known eruption in the past 70,000 years, with a Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) of 8. It occurred around 26,500 years ago and deposited approximately 1,200 km³ of material.[2][3] Tephra from the eruption covered much of the central North Island with ignimbrite up to 200 metres (650 feet) deep, and most of New Zealand was affected by ash fall, with even an 18 cm (7 inch) ash layer left on the Chatham Islands, 1,000 km (620 mi) away. Later erosion and sedimentation had long-lasting effects on the landscape, causing the Waikato River to shift from the Hauraki Plains to its current course through the Waikato to the Tasman Sea.[4] New Zealand's largest lake, Lake Taupō, fills the caldera formed in this eruption.

Taupō's most recent major eruption, the Taupō or Hatepe eruption, took place around 232 CE, and is New Zealand's largest eruption since Oruanui.[5] It ejected some 120 km³ of material (rating 7 on the VEI scale),[6] with around 30 km³ ejected in just a few minutes. It is believed that the eruption column was 50 kilometres (31 mi) high, twice as high as the eruption column from Mount St. Helens in 1980. This makes it one of the most violent eruptions in the last 5000 years (alongside the Tianchi eruption of Baekdu at around 1000 and the 1815 eruption of Tambora). The resulting ash turned the sky red over Rome and China.[7]

Mount Tarawera's eruption around 1310 CE, while not nearly as large, was still substantial, producing 2.5 km³ of lava and 5 km³ of tephra (VEI 5).[8] Because its deposits, stretching from Gisborne to the Bay of Islands, were emplaced around the time that Māori permanently settled New Zealand, they have provided a useful archaeological marker. Tarawera erupted again on 10 June 1886, spewing ash and debris over 16,000 km2 (6,200 sq mi), destroying the Pink and White Terraces and three villages, including Te Wairoa, and claiming the lives of perhaps 120 people.[9] Approximately 2 km³ of tephra was erupted (VEI 5).[8]

Hazards

As well as the direct effects of explosions, lava, and pyroclastic flows, volcanoes pose various hazards to the New Zealand populace. These include tsunamis, break-out floods and lahars from volcanically dammed lakes, ashfall, and other far field effects.

For instance, the Tangiwai disaster occurred on 24 December 1953 when the Tangiwai railway bridge across the Whangaehu River collapsed from a lahar in full flood, just before an express train was about to cross it. The train could not stop in time, and 151 people died. This was ultimately caused by Ruapehu's 1945 eruption, which had emptied the crater lake and dammed the outlet with tephra.

Effects can be widespread even for eruptions of only moderate size. Ash plumes from Ruapehu's 1996 eruption forced the closure of eleven airports, including Auckland International Airport.[10]

Insurance against volcanic damage (along with other natural disasters) is provided by the country's Earthquake Commission.

Cultural references

The Māori had many myths and legends regarding the land's volcanic mountains. Perhaps the most well known regards the relative locations of Taranaki, Tongariro and Pihanga. It holds that the two first-named volcanoes competed for the love of the beautiful Pihanga and, after Tongariro succeeded, the defeated Taranaki moved to its lonely location near New Plymouth.

Another legend recounts the exploits of Ngātoro-i-rangi, a tohunga (priest) who arrived from the ancestral Māori homeland, Hawaiki, on the Arawa waka (canoe). Travelling inland and then looking southward from Lake Taupō, he decided to climb the mountains he saw there. He reached and began to climb the first mountain along with his slave Ngāuruhoe, who had been travelling with him, and named the mountain Tongariro (the name literally means 'looking south'), whereupon the two were overcome by a blizzard carried by the cold south wind. Near death, Ngātoro-i-rangi called back to his two sisters, Kuiwai and Haungaroa, who had also come from Hawaiki but remained on Whakaari / White Island, to send him sacred fire, which they had brought from Hawaiki. This they did, sending the fire in the form of two taniwha (powerful spirits) named Te Pupu and Te Haeata by a subterranean passage to the top of Tongariro. The tracks of these two taniwha formed the line of geothermal fire that extends from the Pacific Ocean and beneath the Taupō Volcanic Zone, and is seen in the many volcanoes and hot springs extending from Whakaari to Tokaanu and up to the Tongariro massif. The fire arrived just in time to save Ngātoro-i-rangi from freezing to death, but Ngāuruhoe had already died by the time Ngātoro-i-rangi turned to give him the fire. For this reason the hole through which the fire ascended, the active cone of Tongariro, is now called Ngauruhoe.

Eruptions in the North Island, such as the Kaharoa eruption of Mt Tarawera in 1314, have been used to help determine the approximate date of arrival of the early Polynesian colonists to about 1280. Fossilized footprints of perhaps second- or third-generation Polynesian colonists have been found in volcanic ash on islands in the Hauraki Gulf.

Geology

Please see the main articles above because as already mentioned almost every kind of volcanism observed on Earth is found in New Zealand. For historic intrusive volcanism please see the section on older volcanism below. There is good evidence for continued intrusive volcanism activity in the central North Island.[11][12][5] A quite recent, large dioritic pluton of the order of 550,000 years old has been dated from drill cores there.[13]

Volcanic areas

While there are remnants of volcanic activity throughout most of New Zealand, there are several areas where they are more obvious, and somewhere activity continues. Since Taranaki's last activity in 1854, all eruptions have been in the Taupō Volcanic Zone or the Kermadec Arc.[14]

Kermadec Arc

The Kermadec Islands are an active volcanic island arc stretching north-northeast from New Zealand's North Island towards Tonga. While only a few volcanoes in the arc are tall enough to form islands, it includes about 30 sizeable submarine volcanoes with many in the South Kermadec Ridge Seamounts at the New Zealand end of the chain. The largest island, Raoul Island, produced a large eruption around 2200 years ago with a VEI of 6.[15] Its activity has continued intermittently since, with its latest eruption occurring in 2006.[16]

Northland

The Northland region contains two recently active volcanic fields, one centered around Whangarei,[17] and the other is the Kaikohe-Bay of Islands volcanic field.[18] The latest activity in the Kaikohe-Bay of Islands field, around 1300 to 1800 years ago, created four scoria cones at Te Puke (near Paihia).[18]

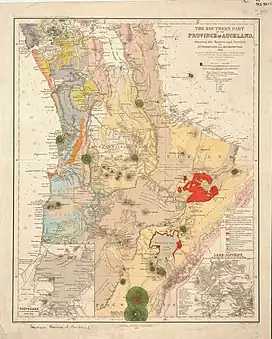

Earlier, during the Miocene, a mainly andesitic volcanic arc ran through Northland and neighbouring regions (including the Three Kings Ridge and northern Coromandel Peninsula), with western and eastern belts active between 25 and 15 million years ago and 23–11 million years ago respectively.[20] Although this produced substantial volcanic edifices, including New Zealand's largest known stratovolcano, the Waitakere volcano,[21] most of these have been eroded away, buried, or submerged, especially in the west, where a series of volcanoes buried offshore stretches south almost to New Plymouth. This is called the Northland-Mohakatino Volcanic Belt.[22] Remnants of these two ancient volcano belts are still exposed in many places, including Whangarei Heads, the Hen and Chickens Islands, around Whangaroa Harbour, Waipoua forest, and the Waitākere Ranges.

Auckland volcanic field

The basaltic Auckland volcanic field is a monogenetic volcanic field underlying much of the Auckland metropolitan area. The field's many vents have produced a diverse array of explosion craters, scoria cones, and lava flows. The largest and most recent is Rangitoto in the Hauraki Gulf, which last erupted 600–700 years ago. Currently dormant, the field is likely to erupt again within the next "hundreds to thousands of years" (based on past events), a short timeframe in geologic terms.[23] Auckland's residents, however, face more danger from volcanoes farther south.[23]

Auckland's volcanoes are believed to be the latest product of an unusual magma source related to local tectonics which is not a classic hot spot, as the earlier volcanic fields are to the south, the opposite expected from movement of the Australian plate over a stationary mantle plume source.[24]

Waikato and South Auckland

Three volcanic fields erupted between 2.7 and 0.5 million years ago, migrating northwards from Mount Pirongia to the Bombay Hills. The earliest of these fields formed the Alexandra Volcanics[25] which is distinguished by large arc volcano tholeiitic cones but did have associated Okete Volcanics which were traditionally more akaline and oxidised and were in the monogenetic volcanic field pattern seen in the later fields. The distinction between the Alexandra and Okete volcanics is not necessarily clear cut and is still being studied. Alexandra Volcanic Group rocks (mostly basalt) cover about 450 km2 amounting to 55 km3 from at least 40 vents. Mount Pirongia and Mount Karioi are part of the main lineament in the group.[26] The later fields are the smallest Ngatutura Volcanics which comprises about 16 volcanoes south of Port Waikato on the west coast and the South Auckland volcanic field with over 80 volcanoes.[27] The magma body that created the Auckland volcanic field is considered to have been related to these outpourings also. Unlike typical hot spots such as the one underlying Hawaii, it does not seem to have stayed still, but instead is migrating northward at a faster pace than the surrounding Indo-Australian Plate. Its motion has been explained as the tip of a propagating crack produced by the twisting of the North Island's crust.[28][24]

Coromandel Volcanic Zone

The extinct Coromandel Volcanic Zone (CVZ) was a volcanic arc stretching from Great Barrier Island in the north, through the Coromandel Peninsula, to Tauranga and the southern Kaimai Ranges in the south. Activity began in the north around 18 million years ago, and was primarily andesitic until around 9–10 million years ago, when it changed to a bimodal basaltic/rhyolitic pattern. Eruptive centres gradually migrated southward,[30] where they transitioned into early activity in the Taupō Volcanic Zone. Later activity in the CVZ and its interface with the Taupō Volcanic Zone is obscured by subsequent events and is not fully understood, but continued in the south until perhaps 1.5 million years ago in the Tauranga Volcanic Centre.[31] Together with the extinct undersea Colville Ridge, the CVZ formed a precursor to the modern Taupō Volcanic Zone and Kermadec Ridge.[32]

Mayor Island / Tūhua

Mayor Island / Tūhua is a peralkaline shield volcano with a caldera partly formed in a large eruption some 7000 years ago. It has exhibited many eruptive styles, and its last eruption may have occurred only 500–1000 years ago.[33] The island's Maori name, Tuhua, refers to the obsidian they found on the island and prized for its sharp cutting edge.

Taupō Volcanic Zone

About 350 kilometres long by 50 kilometres wide, the Taupō Volcanic Zone (TVZ) is the world's most productive area of recent silicic volcanic activity,[34] with the highest concentration of young rhyolitic volcanoes.[35] Mount Ruapehu marks its southwestern end, and it continues up through Ngauruhoe, Tongariro, Lake Taupō, the Whakamaru, Mangakino, Maroa, Reporoa, and Rotorua calderas, the Okataina Volcanic Complex (including Mount Tarawera) and 85 kilometres beyond Whakaari / White Island to the submarine Whakatāne Seamount. The TVZ also contains numerous smaller volcanoes, along with geysers and geothermal areas. Volcanic eruptions began here around two million years ago, with silicic eruptions starting around 1.55 million years ago, as activity shifted southeast from the Coromandel Volcanic Zone.[31]

Taranaki

Volcanism in the Taranaki region has migrated southeastward during the last two million years. Beginning in the Sugar Loaf Islands, near New Plymouth, activity then shifted to Kaitake (580,000 years ago) and Pouakai (230,000 years ago) before creating the large stratovolcano called Mount Taranaki, (former name Mount Egmont), which last erupted in 1854, and its satellite vent, Fanthams Peak.[36] This southeastward migration is the continuation of the 25 million year activity of the Northland-Mohakatino Volcanic Belt that extends mainly under the present Tasman Sea from the west of Northland down to Mount Taranaki.[22]

Chatham Islands

The higher portions of the Chatham Islands are formed from volcanic rock that is up to 81 million years old, although lava flows on the northern shore of Chatham Island date back only about five million years.[37]

Banks Peninsula

Banks Peninsula comprises the eroded remnants of two large stratovolcanoes, Lyttelton, which formed first, and Akaroa. These formed by intraplate volcanism through continental crust approximately eleven to eight million years ago (Miocene). The peninsula formed as offshore islands, with the volcanoes reaching to about 1,500 m above sea level. Two dominant craters were eroded, then flooded, to form the Lyttelton and Akaroa Harbours. The portion of crater rim lying between Lyttelton Harbour and Christchurch city forms the Port Hills.

Oamaru

Small sub-alkaline basalt to basaltic andesite Surtseyan volcanoes on the submerged continental shelf formed what was historically termed the Waiareka-Deborah volcanic group and now called the Waiareka-Deborah volcanic field in the area around Oamaru around 35 to 30 million years ago.[38][39] A monogenetic volcanic field of more alkaline composition eruptives, with stronger surface features, as they are younger, extends north of Dunedin overlapping the southern Waiareka-Deborah volcanic field, and these volcanoes have now been characterised to be part of the Dunedin volcanic group.[40]

Southern Alps

The Alpine Dyke Swarm of volcanic intusion took place about 25 million years ago and is located near Lake Wānaka in the Southern Alps.[41]

Dunedin

The Dunedin Volcano formed during the Miocene, beginning with basaltic eruptions on the Otago Peninsula is the largest volcano in the large Dunedin volcanic group.[40] Large central-vent structures formed, and then large domes, with seawater interacting explosively with erupting submarine magma.[42]

Solander Islands

The Solander Islands, a small chain of uninhabited islets close to the western end of the Foveaux Strait, are the emergent portions of a large extinct andesitic volcano that last erupted around 50,000 to 150,000 years ago.[43] Caused by the subduction of the Australian Plate beneath the Pacific Plate, it is the only volcano associated with this subduction zone that protrudes above the sea.[44][45]

Subantarctic islands

The majority of New Zealand's widely separated subantarctic islands are primarily volcanic in origin, including Auckland Island, Campbell Island / Motu Ihupuku, and Antipodes Island.[37] These are mainly Miocene intraplate volcanoes with ages decreasing towards the northeast, although Antipodes Island may have been active during the last 20,000 years.

Older volcanism

Older remnants of volcanism are also found in several places around New Zealand. These were generally formed either when New Zealand still formed part of the Gondwana supercontinent, or while Zealandia was rifting away from the rest of Gondwana, although some have been emplaced in their current setting more recently. (New Zealand is the main part of the submerged microcontinent of Zealandia that currently emerges above the sea.)

A band of granitic intrusions covering over 10,000 km2, the Median Batholith, stretches from Stewart Island / Rakiura through Fiordland, and again through the West Coast and Nelson after interruption by the Alpine Fault. This was produced between 375 and 105 million years ago in the course of subduction-related volcanism in a long mountain range along the Gondwanan coast somewhat like today's Andes. Two more batholiths, the Karamea-Paparoa and Hohonu Batholiths, are also found on the West Coast.

Basaltic lava flows, dikes, and tuff from fissure eruptions between 100 million and 66 million years ago, during Zealandia's separation from Gondwana, are found in Marlborough, the West Coast and offshore further west. Ultramafic intrusions are found in Marlborough and north Canterbury, including at the summit of Tapuae-o-Uenuku, the country's highest mountain outside the Southern Alps / Kā Tiritiri o te Moana.[46] The Mount Somers volcanics that erupted from 100 to 80 million years ago extend to Banks Peninsula but are mostly buried there by more recent volcanism.

Rhyolitic ignimbrite[47] and tuff deposits found in Otago at Shag Point / Matakaea and in the Kakanui Mountains that were originally dated in the range 107 to 101 million years ago[48] are now both dated to 112 ± 0.2 million years ago and so likely come from a large singe event.[49]

The Hikurangi Plateau is an oceanic plateau on the Pacific Plate that attached to the Chatham Ridge after being partially subducted under it, and is now subducting under the North Island. It likely formed in one of the world's largest volcanic outpourings, the greater Ontong Java event.

Ophiolites, volcanic deposits from the ocean floor, have been incorporated into the continental basement of New Zealand in the Dun Mountain Ophiolite Belt, found at both ends of the South Island, and in Northland.

See also

- North Island surface volcanism (for more geology details)

- South Island surface volcanism (for more geology details)

- Geothermal areas in New Zealand

- List of disasters in New Zealand by death toll

- List of earthquakes in New Zealand

- List of volcanoes in Antarctica (for volcanoes in New Zealand's Ross Dependency)

- List of volcanoes in New Zealand

Notes

- Heather Catchpole. Islands of fire Archived 23 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Cosmos Magazine.

- Wilson, Colin J. N. (2001). "The 26.5 ka Oruanui eruption, New Zealand: an introduction and overview". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 112 (1–4): 133–174. Bibcode:2001JVGR..112..133W. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(01)00239-6.

- Wilson, Colin J. N.; et al. (2006). "The 26.5 ka Oruanui Eruption, Taupo Volcano, New Zealand: Development, Characteristics and Evacuation of a Large Rhyolitic Magma Body". Journal of Petrology. 47 (1): 35–69. Bibcode:2005JPet...47...35W. doi:10.1093/petrology/egi066.

- Manville, Vern; Wilson, Colin J. N. (2004). "The 26.5 ka Oruanui eruption, New Zealand: a review of the roles of volcanism and climate in the post-eruptive sedimentary response". New Zealand Journal of Geology & Geophysics. 47 (3): 525–547. doi:10.1080/00288306.2004.9515074.

- Illsley-Kemp, Finnigan; Barker, Simon J.; Wilson, Colin J. N.; Chamberlain, Calum J.; Hreinsdóttir, Sigrún; Ellis, Susan; Hamling, Ian J.; Savage, Martha K.; Mestel, Eleanor R. H.; Wadsworth, Fabian B. (1 June 2021). "Volcanic Unrest at Taupō Volcano in 2019: Causes, Mechanisms and Implications". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 22 (6): 1–27. Bibcode:2021GGG....2209803I. doi:10.1029/2021GC009803.

- "Taupo – Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- Wilson, C. J. N.; Ambraseys, N. N.; Bradley, J.; Walker, G. P. L. (1980). "A new date for the Taupo eruption, New Zealand". Nature. 288 (5788): 252–253. Bibcode:1980Natur.288..252W. doi:10.1038/288252a0. S2CID 4309536.

- "Okataina: Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- Dench, p 114.

- Mass aircraft grounding possible in NZ too scientists say Archived 22 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine, media release, GNS Science, 19 April 2010.

- Gómez-Vasconcelos, Martha Gabriela; Villamor, Pilar; Cronin, Shane; Procter, Jon; Palmer, Alan; Townsend, Dougal; Leonard, Graham (2017). "Crustal extension in the Tongariro graben, New Zealand: Insights into volcano-tectonic interactions and active deformation in a young continental rift". GSA Bulletin. 129 (9–10): 1085–1099. Bibcode:2017GSAB..129.1085G. doi:10.1130/B31657.1.

- Benson, Thomas W.; Illsley-Kemp, Finnigan; Elms, Hannah C.; Hamling, Ian J.; Savage, Martha K.; Wilson, Colin J. N.; Mestel, Eleanor R. H.; Barker, Simon J. (2021). "Earthquake Analysis Suggests Dyke Intrusion in 2019 Near Tarawera Volcano, New Zealand". Frontiers in Earth Science. 8: 604. Bibcode:2021FrEaS...8..604B. doi:10.3389/feart.2020.606992. ISSN 2296-6463.

- Arehart, G.B; Christenson, B.W; Wood, C.P; Foland, K.A; Browne, P.R.L (2002). "Timing of volcanic, plutonic and geothermal activity at Ngatamariki, New Zealand". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 116 (3–4): 201–214. Bibcode:2002JVGR..116..201A. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(01)00315-8. ISSN 0377-0273.

- Volcanoes of New Zealand to Fiji, Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution.

- "Smithsonian Global Volcanic Program:Raoul Island".

- "Raoul Island". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- "Whangarei Volcanic Field". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- "Kaikohe-Bay of Islands". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- Ewen Cameron; Bruce Hayward; and Graeme Murdoch (1997). A Field Guide to Auckland: Exploring the Region's Natural and Historic Heritage, p. 168. Godwit Publishing Ltd, Auckland. ISBN 1-86962-014-3.

- Hayward, Bruce W.; Black, Philippa M.; Smith, Ian E. M.; Ballance, Peter F.; Itaya, Tetsumaru; Doi, Masako; Takagi, Miki; Bergman, Steve; Adams, Chris J.; Herzer, Richard H.; Robertson, David J. (2001). "K-Ar ages of early Miocene arc-type volcanoes in northern New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 44 (2): 285–311. doi:10.1080/00288306.2001.9514939. S2CID 128957126. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- Hayward, Bruce W. (2017). Out of the Ocean, Into the Fire: History in the Rocks, Fossils and Landforms of Auckland, Northland and Coromandel (PDF). Geoscience Society of New Zealand. title page. ISBN 9780473395964. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- Bischoff, Alan; Barriera, Andrea; Begg, Mac; Nicola, Andrew; Colea, Jim; Sahoo, Tusar (2020). "Magmatic and Tectonic Interactions Revealed by Buried Volcanoes in Te Riu-a-Māui/Zealandia Sedimentary Basins". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 63: 378–401. doi:10.1080/00288306.2020.1773510. S2CID 221380777.

- Beca Carter Hollings & Ferner (2002). Contingency Plan for the Auckland volcanic field, Auckland Regional Council Technical Publication 165. Accessed 12 May 2008.

- Nemeth, Karoly; Kereszturi, Gabor; Agustín-Flores, Javier; Briggs, Roger Michael (2012). "Field Guide Monogenetic volcanism of the South Auckland and Auckland Volcanic Fields". Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- Briggs, R.M.; Goles, G.G. (1984). "Petrological and trace element geochemical features of the Okete Volcanics, western North Island, New Zealand". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 6: 77–88. doi:10.1007/BF00373712. S2CID 129834459.

- Geology of the Raglan-Kawhia Area: Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences (N.Z.), Barry Clayton Waterhouse, P. J. White 1994 ISBN 0-478-08837-X

- Briggs, R. M.; Itaya, T.; Lowe, D. J.; Keane, A. J. (1989). "Ages of the Pliocene-Pleistocene Alexandra and Ngatatura Volcanics, western North Island, New Zealand, and some geological implications". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 32 (4): 417–427. doi:10.1080/00288306.1989.10427549. hdl:10289/5260.

- Cox, Geoffrey J.; Hayward, Bruce W. (1999). The Restless Country: Volcanoes and earthquakes in New Zealand. HarperCollins. ISBN 1-86950-296-5.

- Hayward, B. (2008). Protecting NZ's Heritage Natural Arches, Geological Society of New Zealand Newsletter 145 (March), 23.

- C. J. Adams; I. J. Graham; D. Seward; D. N. B. Skinner (1994). "Geochronological and geochemical evolution of late Cenozoic volcanism in the Coromandel Peninsula, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 37 (3): 359–379. doi:10.1080/00288306.1994.9514626.

- R. M. Briggs; B. F. Houghton; M. McWilliams; C. J. N. Wilson (2005). "40Ar/39Ar ages of silicic volcanic rocks in the Tauranga-Kaimai area, New Zealand: dating the transition between volcanism in the Coromandel Arc and the Taupo Volcanic Zone". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 48 (3): 459–469. doi:10.1080/00288306.2005.9515126.

- K.N. Nicholson; P.M. Black; P.W.O. Hoskin; I.E.M. Smith (2004). "Silicic volcanism and back-arc extension related to migration of the Late Cainozoic Australian–Pacific plate boundary". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 131 (3–4): 295–306. Bibcode:2004JVGR..131..295N. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(03)00382-2.

- "Mayor Island". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- Karl D. Spinks, J.W. Cole, & G.S. Leonard (2004). Caldera Volcanism in the Taupō Volcanic Zone. In: Manville, V.R. (ed.) Geological Society of New Zealand/New Zealand Geophysical Society/26th New Zealand Geothermal Workshop, 6–9 December 2004 , Taupo: field trip guides. Geological Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 117B.

- Volcanology highlights, Volcanoes of New Zealand to Fiji, Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution.

- Locke, Corinne A.; John Cassidy (1997). "Egmont Volcano, New Zealand: three-dimensional structure and its implications for evolution". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 76 (1–2): 149–161. Bibcode:1997JVGR...76..149L. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(96)00074-1.

- K. S. Panter, J. Blusztajn, S. R. Hart, P. R. Kyle, R. Esser, W. C. McIntosh (2006). The Origin of HIMU in the SW Pacific: Evidence from Intraplate Volcanism in Southern New Zealand and Subantarctic Islands

- Simone Hicks, PhD proposal: Ecological and sedimentological evolution of the volcanically active Oligocene continental shelf, east Otago, New Zealand, Geology Department, University of Otago. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- R. A. F. Cas; C. A. Landis; R. E. Fordyce (1989). "A monogenetic, Surtla-type, Surtseyan volcano from the Eocene-Oligocene Waiareka-Deborah volcanics, Otago, New Zealand: A model". Bulletin of Volcanology. 51 (4): 281–298. Bibcode:1989BVol...51..281C. doi:10.1007/BF01073517. S2CID 129657592.

- Scott, James M.; Pontesilli, Alessio; Brenna, Marco; White, James D. L.; Giacalone, Emanuele; Palin, J. Michael; le Roux, Petrus J. (2020). "The Dunedin Volcanic Group and a revised model for Zealandia's alkaline intraplate volcanism". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 63 (4): 510–529. doi:10.1080/00288306.2019.1707695. S2CID 212937447.

- Cooper, Alan F. (2020). "Petrology and petrogenesis of an intraplate alkaline lamprophyre-phonolite-carbonatite association in the Alpine Dyke Swarm, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 63 (4): 469–488. doi:10.1080/00288306.2019.1684324. S2CID 210266079.

- ""Eruptions and deposition of volcaniclastic rocks in the Dunedin Volcanic Complex, Otago Peninsula, New Zealand", Ulrike Martin". Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- Mortimer, N.; Gans, P.B.; Foley, F. V.; Turner, M. B.; Daczko, N.; Robertson, M.; Turnbull, I. M. (2013). "Geology and Age of Solander Volcano, Fiordland, New Zealand". Journal of Geology. 121 (5): 475–487. doi:10.1086/671397.

- Keith Lewis, Scott D. Nodder and Lionel Carter. 'Sea floor geology – Solander Island', Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated 2 March 2009. Accessed 18 April 2010.

- Mortimer, N.; Gans, P.B.; Mildenhall, D.C. (2008). "A middle-late Quaternary age for the adakitic arc volcanics of Hautere (Solander Island), Southern Ocean". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 178 (4): 701–707. Bibcode:2008JVGR..178..701M. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2008.09.003. ISSN 0377-0273.

- Baker, I. A.; Gamble, J. A.; Graham, I. J. (1994). "The age, geology, and geochemistry of the Tapuaenuku Igneous Complex, Marlborough, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology & Geophysics. 37 (3): 249–268. doi:10.1080/00288306.1994.9514620.

- Steiner, A.; Brown, D. A.; White, A. J. R. (1959). "Occurrence of ignimbrite in the Shag Valley, North-east Otago". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 2 (2): 380–384. doi:10.1080/00288306.1959.10417656.

- Adams, C.J.; Raine, J.I. (1988). "Age of Cretaceous silicic volcanism at Kyeburn, Central Otago, and Palmerston, eastern Otago, South Island, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 31 (4): 471–475. doi:10.1080/00288306.1988.10422144.

- Tulloch, AJ; Ramezani, J; Mortimer, N; Mortensen; J; van den Bogaard, P; Maas, R (2009). "Cretaceous felsic volcanism in New Zealand and Lord Howe Rise (Zealandia) as a precursor to final Gondwana break-up". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 321 (1): 89–118. Bibcode:2009GSLSP.321...89T. doi:10.1144/SP321.5. S2CID 128898123.

References

- Dench, Alison; Essential Dates: A Timeline of New Zealand History, Auckland: Random House, 2005 ISBN 1-86941-689-9