Wallachian military forces

The military of Wallachia existed throughout the history of the country. Starting from its founding to 1860, when it was united with the Moldavian army into what would become the Romanian Army.[1]

.jpg.webp)

The army mainly consisted of light cavalry which was used in hit-and-run tactics, though various other units existed as well.[2][3] Between the 16th and 18th centuries, the army was mostly formed from mercenary units.[4] In 1830, following the Organic Regulation, the standing army of Wallachia was created.[5]

The Wallachian fleet used riverboats of various sizes between the 15th and 17th centuries. In 1794, a small flotilla was created with the approval of The Porte.[6] After the regulations of 1830, a military flotilla was created as well.[7]

Middle Ages

Before the establishment of Wallachia

Before the formation of a Wallachian state, some Romanian leaders controlled lands south of the Carpathians. During the Mongol invasion of Europe, two such leaders, Bezerenbam and Mișelav, fought against the invading Mongol armies. Bezerenbam's army was defeated in the Ilaut Country, while Mișelav's army was defeated by Budjek.[8]

In 1277, the Wallachian voivode Litovoi, first mentioned in the Diploma of the Joannites, fought against the Hungarians over the lands claimed by the Hungarian crown. Litovoi was killed in the battle, and his brother, Bărbat, was captured and forced to pay a ransom and recognize Hungarian rule.[9]

14th–15th centuries

One of the first military actions after the founding of Wallachia was the Battle of Velbazhd in 1330. There, an army led by Basarab I fought alongside the Bulgarians. The battle ended in a defeat.[10]

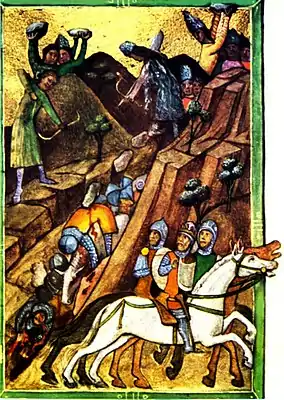

In the same year, Wallachia was invaded by Charles I of Hungary who was seeking to recapture the "marginal lands" held by Basarab.[11] The Hungarian royal army captured Severin in September, appointing Dionysius Széchy as Ban. Due to the poor supplies of Charles' army, he was compelled to sign an armistice and retreat from Wallachia.[12] His army was ambushed by Basarab in a mountain valley on 9 November. According to historian Constantin Rezachevici, in the first phase of the battle which lasted two days, the Hungarian army was stopped in the valley and attacked with ranged weapons. The last two days of battle were primarily fought in melee combat, which marked the character of the battle.[13] While portrayed only as peasants armed with bows and rocks in the Illuminated Chronicle, the Wallachian army of Basarab was just as well equipped as the King's army as noted by Stephen, the son of the Cuman Ispán Parabuh.[14]

Wars with Hungary continued during the reign of Vladislav Vlaicu, with Vlaicu defeating an army led by Nicholas Lackfi in the autumn of 1368, though he later submitted to Louis I.[15] For a battle against the Hungarians, Radu I prepared his army with armor from Venice as described in Cronaca Carrarese by Galeazzo and Bartolomeo Gatari. His army was however defeated in the clash according to the chronicle.[16]

During the reign of Mircea the Elder, Wallachia first faced the Ottomans. A victory was achieved at the Battle of Rovine,[17] and Mircea also participated in the Battle of Nicopolis.[18] In 1430, a document issued by Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg mentioned that Wallachia and Moldavia could raise an army of 10,000 pancerati,[19] and in 1448 a contingent of 4,000 archers led by the Voivode participated in the Battle of Kosovo.[20]

Due to the constant internal and external conflicts, Vlad Dracula organized a small army of 6,000 to 8,000 soldiers composed of small land owners, boyars, courtiers, and a hired personal guard of trabants from Transylvania. Vlad also made use of artillery, which was likely operated by foreign mercenaries.[21][22]

With this army, Vlad campaigned against the Transylvanian Saxons who supported his rivals.[23] He also defeated an Ottoman army led by Hamza Bey in 1460.[24] In 1462, Vlad launched a campaign south of the Danube. Dividing his army into six columns, he attacked strategic settlements near the river. Vlad led the army heading towards Nicopolis.[25] During this attack, he utilized culverins in his attack on Svishtov,[26] and also destroyed a number of 50 Ottoman ships.[27] During the night attack on Mehmet's camp near Târgoviște in 1462, the Voivode's army took heavy losses.[23]

The large host

The large host (oastea cea mare) was an army that consisted of peasants and city dwellers. The number of soldiers in this army could reach 30 to 40,000. Once the Prince ordered the call to arms, special envoys were dispatched to the territory to deliver the message. Territorial governors (vornici de județ and vornici de târg) then passed the call to arms to villages and towns. In an Ottoman document from 1521, it is specified that this mobilization took at least 20 days.[21]

The first documented mention of the large host comes from the reign of Mircea the Elder in 1408 when the Voivode granted a village to the abbot of the Snagov monastery, who was exempt from all taxes but not from service in the large host. Vlad the Impaler tried to raise this army in the summer of 1462, during Mehmet's invasion. Due to the relatively short time, Vlad failed to form the army and only relied on his small host. From the first half of the 16th century, this army was no longer raised. The last mention of the large host comes from Vlad Înecatul, who mentioned that villagers were still required to serve in this army. After this mention, the large host never appeared in any documents or other sources.[21]

Early Modern Period

16th–17th centuries

During his four reigns as Voivode between 1522 and 1529, Radu of Afumați fought in 20 battles with Ottoman-supported pretenders to the throne such as Vladislav III and Mehmed Bey.[28] He won an important victory against Mehmed Bey at Grumazi. Forced out of the country in a new campaign launched by Mehmed, Radu gained support from John Zápolya, the Voivode of Transylvania, and defeated the pretender in the autumn of 1522.[29]

The army of Radu Paisie participated in the Ottoman expedition in Hungary under the command of Ban Șerban of Izvorani. In 1538, the Voivode himself led a 3,000-strong army in support of the invasion of Moldavia against Petru Rareș.[30] To better equip his army with cannons for an upcoming anti-Ottoman offensive, Voivode Petru Cercel established a bronze cannon foundry in Târgoviște.[31] The foundry, organized with the help of Venetian craftsmen,[32] functioned until the end of his reign.[33]

Voivode Michael the Brave carried out several successful campaigns. In 1594, he captured several Turkish forts along the Danube and won at the Battle of Călugăreni a year later. With new support from Transylvania, Michael launched another offensive against the Ottomans in the summer of 1595, continuing with his attacks as far as Adrianopole. His anti-Ottoman campaigns lasted until 1599. After the peace with the Ottomans, Michael then attacked Transylvania and disposed of Andrew Báthory following the Battle of Șelimbăr.[34][35] His last victory came at the Battle of Guruslău against Sigismund Báthory in 1601.[34]

Besides the local troops of Roșii, Călărași, and Dorobanți, Michael's armies were composed of various mercenaries including Cossacks, Székelys, Serbs, Moldavians, and Germans.[36] Over the course of his reign their number increased, and by 1598 there were over 13,000 mercenaries.[37]

During the time of Leon Tomșa, there were 10,000 horsemen and 2,000 footmen in the Wallachian army, as the Voivode recounted to Paul Strassburg, a secret counselor of King Gustav II Adolph.[38] Prince Matei Basarab increased the number of soldiers in his army. The army, divided into Roșii, servants (Dorobanți and Călărași), and mercenaries reached around 40,000 soldiers. In 1646, Matei Basarab hired additional mercenaries, the Serbian Seimeni. With this army and with his Polish allies, he defeated Vasile Lupu at the Battle of Finta.[39]

As the Seimeni did not receive their pay after the battle, they began revolting against the Voivode. Initially, the revolt was stopped with the threat of invasion from George II Rákóczi. Due to the cost of maintaining the army, the new Prince, Constantin Șerban, disbanded the Seimeni in 1655. After this action, the uprising started again, this time the Seimeni being joined by the Dorobanți and some Roșii, and was aimed towards the boyars. The rebelling army reached a number of 20,000 soldiers and 30 cannons. They plundered churches, monasteries, and boyar estates, killing 32 boyars in the process. With help from Rákóczi, the rebel army led by Hrizea of Bogdănei was defeated in battle at Șoplea after the betrayal of some rebel commanders who joined forces with the Prince. The remnants of the Seimeni were further defeated at Târgul Bengăi. The uprising, although subsided, continued until 1657.[39]

18th century

After the establishment of the Phanariot rule, the armies of Wallachia and Moldavia continued their service. Like a century prior, the Wallachian army was mainly made up of mercenaries.[4] A total number of 27 different types of troops existed throughout the century. Their equipment and uniforms varied between each troop type. Though the boyars who led them were not trained at military academies, they studied the military tactics of their time and instructed their troops accordingly.[40] While the Phanariot armies carried out their tasks well during peacetime, such as guarding the Princely Courts, borders, and towns, and ensuring public order; during wartime, the efficiency of these armies was limited due to the poor training of the troops, lack of equipment, and the lack of a well-trained officer corps. Some victories were however achieved.[41]

During the Austro-Turkish War of 1737–1739, an army led by Spătar Ioan Nicolae Mavrocordat, Constantin Mavrocordat's brother, together with an Ottoman detachment defeated the Austrian troops in the Argeș and Muscel counties in September 1737. On 18 October, the Austrian vanguard of 5,000 Hungarian Hussars and 300 Germans was attacked and destroyed at Pitești, forcing the main army corps to retreat towards Oltenia. The Wallachian army continued the offensive and further defeated a 10,000-strong Imperial army at Râmnicu Vâlcea in November. By December 1737, all of Oltenia was under Wallachian control. The next year, an Austrian attack was repelled at Cozia and the troops under Constantin Mavrocordat forced a Russian army to retreat to Transylvania.[42] Other victories were registered against the Austrians along the Wallachian border by the army of Nicolae Mavrogheni in the Russo-Turkish War (1787–1792) before the allied victory at the Battle of Focșani.[43]

The Wallachian soldiers mainly wore green and blue colored uniforms, with red being reserved for nobles, though eventually red was adopted by officers and certain troops as well. Yellow uniforms were sometimes worn by officers, while white ones were worn by the Princely Court guards. Other troops might have worn uniforms in multiple colors. Some irregular troops like the potecași wore peasant clothes.[44]

Modern Wallachian Army

During the Russian occupation of the Danubian Principalities from 1829 to 1834, the Wallachian army was modernized. Under the supervision of Russian General Pavel Kiseleff, a Wallachian standing army was created. In April 1830, a committee composed of General Starov, Lieutenant Alexandru Ghica, Colonel Ment, and Lieutenant-colonel Ion Odobescu was formed.[5]

According to the drafted law, the Wallachian army was to be organized into 6 infantry battalions and 6 cavalry squadrons. The core of this army were the Pandurs, which formed six battalions. Around June 1830, it was announced that the new army would have 6 cavalry squadrons, and 3 regiments (the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Line infantry regiments), each with 2 infantry battalions.[5]

The commander of the "militia" (army) was Spătar Alexandru Ghica, while the officer corps was made up of boyars and sons of boyars. The regimental commanders, appointed in July 1830, were Colonel Emanuel Băleanu and Major I. Solomon. Alexandru Ghica's brother, Costache, became the inspector of the cavalry. The reception of certain Pandur chiefs, like Christian Tell, as officers in the army caused some displeasure among the boyars.[5]

1848 and the battle of Dealul Spirii

During the 1848 revolution, as the Ottoman army led by Omar Pasha and Fuat Pasha crossed into Wallachia, an armed resistance began to be organized. Military units of the army were rallied at the Râureni camp by Gheorghe Magheru. Due to the poor economic conditions which did not allow the resistance to properly arm itself, and due to the hesitation of some revolution leaders, these troops never entered combat with the Ottomans.[45]

On 24 September, the Ottomans set up their camp at Cotroceni, being faced by several thousand peasants who tried to defend Bucharest. After arresting the revolution leaders, the Ottoman army began marching towards the city on 25 September, dividing their forces in three columns. The first column, led by Mehmed Pasha, passed through Văcărești. The larger second column, led by Fuat and Omar Pasha, forced their entry through the barrier at Beilic Bridge (Calea Șerban Vodă). The peasants tried to stop the advance of the Ottoman column, however, due to the lack of weapons they were defeated by the Turkish cavalry with hundreds of peasants being killed in the fight.[45]

The third Ottoman column, led by Kerim Pasha advanced along Calea Pandurilor, heading to the barracks on Dealul Spirii. Despite being ordered not to do so, Captain Pavel Zăgănescu prepared the fire company for armed resistance. At the same time, Colonel Radu Golescu with the 2nd Line Infantry Regiment and the 7th Company of the 1st Line Infantry Regiment,[46] refused to hand over the barracks to the Ottomans. In the ensuing battle, the Wallachain soldiers managed to hold their lines. To try and break them, the Ottomans used their cannons, causing casualties among the defenders. The firemen rushed the two pieces of artillery and managed to turn them on the Ottomans. Due to the intervention of an Ottoman cavalry squadron, however, the Wallachians were pushed back. Seeing the determined defense of their opponents, the Ottomans went on to negotiate with them. In exchange for laying down their weapons, they were to be guaranteed safe exit from the barracks, however, once a group of unarmed soldiers left the barracks the Turks opened fire. Eventually, the barracks were captured, and the rest of the city was pacified as well.[45]

Crimean War

In June 1853, Russian troops crossed into the two Danubian Principalities and occupied them without declaring war on the Ottoman Empire. The Russian administration decided to incorporate the Wallachian and Moldavian troops into the Imperial Russian Army. At the same time, volunteer detachments were formed to fight against the Ottomans. Due to the entry of the United Kingdom and France into the war on the side of the Ottomans, the Russians were forced to retreat from the Principalities.[47]

Following the Boiagi-Kioi agreement from 14 July 1854, the Principalities were to come under a joint Austrian-Ottoman occupation. An Ottoman and an Austrian brigade were to be stationed in Bucharest, and General Johann Baptist Coronini-Cronberg was named commander of the occupation troops. The occupation lasted until 1857.[47]

Equipment and tactics

The strategies used by Wallachia, as in Moldavia, were mostly defensive in nature. In order to disrupt an enemy's advance in the country, the population was often required to retreat to the wooded or mountainous regions, while the army engaged in hit-and-run tactics and avoided direct confrontations. This was done to delay the advance of an army and to try and lure the enemy into more defensible places like marshes, wooded areas, or mountain passes.[2]

The equipment and weapons of the Wallachian soldiers during the Middle Ages were Western-like with melee weapons like lances, swords, and maces. Later, with the influence of the Ottoman Empire, eastern style sabers were adopted. Ranged weapons used were bows and crossbows. The bows were made of hazel, hornbeam, ash or elm wood and their string was made of flax, hemp, or bowels. According to historian Radu Rosetti, the Wallachian archers could shoot about 10-12 arrows per minute, up to a distance of 220 m (720 ft). Guns in Wallachia were first mentioned in the mid-15th century, Vlad Dracul used two bombards during the siege of Giurgiu in 1445 as part of the Burgundian crusade led by Walerand de Wavrin.[2] The use of wagon forts by Wallachia was first noted during the battle of Râmnicu Sărat in 1473, when Radu the Handsome used one against the army of Stephen the Great of Moldavia. After the battle, the Moldavians captured this fort.[48]

Like Moldavia, Wallachia predominantly used light cavalry, therefore they were lightly equipped with their defensive equipment mainly consisting of a shield of different shapes (round, triangular, or winged).[3] Gambesons and mail armor were also used.[49] The viteji and the boyars, could be equipped with heavier equipment including plate armor. For example, according to the Italian chronicle "Cronaca Carrarese", Radu I of Wallachia acquired a number of 10,000 suits of armor from the Republic of Venice around the year 1377.[14][16] In a document issued by John Zápolya to the Saxons of Brașov regarding a ban imposed by the King on the arms trade with Wallachia in 1522, it is detailed that the Saxons were bringing many weapons and armor to Transylvania from Hungary, and then selling them to Wallachia.[50]

Organization

From the middle ages through the early modern period, the soldiers (voinici) of the Wallachian army were organized in three types of military units:[51]

Units

.png.webp)

The Wallachian Army used various units between the 14th and the 19th centuries:

- Arnăuți - initially Albanian mercenaries. By the end of the 18th century the Aranut troops included other ethnicities as well.[40]

- Călărași - irregular cavalry recruited from the country.[55]

- Ciohodari - servants of the Princely Court, acted as the personal bodyguards of the Voivode in the 18th century.[56]

- Dorobanți - infantry and cavalry soldiers, the term is derived either from the German "Trabant" or Hungarian "Darabant".[55]

- Fuștași - soldiers armed with the "fuște", a type of spear. They were assigned as personal guards of the Voivode.[56]

- Mocani - Wallachian border guard corps formed in the first half of the 18th century and tasked with defending the border with Moldavia.[57]

- Seimeni - Serb mercenaries first recruited by Matei Basarab.[39]

- Panduri - irregular troops, appeared in Imperial Oltenia in the 18th century and acted as a police force.[55]

- Panțâri - a type of cuirassiers,[58] appeared in the 16th century. The term is derived from the German "panzer" meaning "armor".[56]

- Plăieși - border guard troops from mountainous areas.[57]

- Potecași - border guard cavalry troops that defended mountain passes.[55]

- Poterași - irregular light cavalry, used as police troops.[55]

- Roșii - also referred to as cervenii, a type of cavalry which appeared in the late 16th century. Formed during the reign of Mihnea II from the previous curteni, they were exempt from certain taxes. They wore red colored uniforms.[55][59]

- Tălpași - infantry corps formed by Șerban Cantacuzino from the corps of the Dorobanți.[57]

- Trabanți - appeared during the reign of Vlad the Impaler, they were mercenaries recruited from Transylvania and acted as a personal guard of the Voivode.[59]

- Ulani - light cavalry armed with lances.[55]

- Vânători - during peacetime they worked as hunters and defended the border regions, during wars they were called to the army. They were exempt from certain taxes.[57]

- Viteji - synonymous with "curteni" ("courtiers") in Wallachia according to Nicolae Stoicescu,[60] small land-owners with permanent military duties. They were the equivalent of the court knights from the Kingdom of Hungary (milites aulae).[61]

Fleet

The first mention of Wallachia's use of ships for military operations comes from Jean de Wavrin, who wrote about the 1445 Burgundian expedition in Wallachia. During this expedition led by Walerand de Wavrin, the Wallachain Voivode Vlad Dracul offered to guide the Burgundian fleet on the Danube. A number of 40 or 50 monoxyles with 500 soldiers were sent to aid the eight crusader galleys.[62] These kinds of boats might have also been used by Vlad the Impaler during his 1462 campaign south of the Danube.[22]

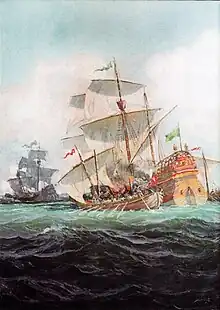

During the reign of Michael the Brave, the voivode constructed șăici of various sizes to arm his fleet. These were used to harass Ottoman commercial ships on the river. According to Turkish chronicler Mustafa Selaniki, in 1596 the Wallachians used some 200 șăici to transport an army of over 2,000 soldiers and attack Ottoman positions in the Babadag region. In 1598, these ships were also used to carry out an attack on Vidin, transporting soldiers, horses, artillery, and ammunition. The șaica along with other boats was further used in the attack against Nicopolis.[63]

Voivode Constantin Brâncoveanu also encouraged naval construction. During his reign, the so-called Brâncovean caïques were built. These caïques were similar to galleys, being crewed by 28 oarsmen, one or two gunners, a helmsman, and a commander, and could transport up to 100 soldiers.[64]

In 1793, Alexander Mourouzis obtained the approval of The Porte to build a small flotilla of "bolozane, șăici, caïques, and other vessels, to carry out the emperor's orders". For this, he issued the "Hrisov for the country's ships, which are to sail on the waters of the Danube" (Hrisov pentru corăbiile țărei, ce sunt a umbla pe apa Dunărei). In 1794, 5 large sailing ships and 16 smaller vessels were built, followed by two gunboats a year later.[6]

With the establishment of the regular armies of Wallachia and Moldavia, each state created a flotilla of 26 row boats. The Wallachian boats were constructed in Giurgiu. These were crewed by army soldiers and tasked with patrolling the port areas. Between 1844 and 1845, the river police corps was equipped with three gunboats built in Austria and with another 42 boats. Of the three, one was armed with two 3-pounder guns and two 1-pounder guns, and the other two were armed with one 3-pounder. The gunboats patrolled the ports of Brăila, Giurgiu, and Calafat. In 1851, another gunboat was purchased.[7]

See also

References

- "Repere istorice". mapn.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- Neagoe 2019, pp. 158–159.

- Cîmpeanu 2022, p. 196.

- Pogăciaș 2016, p. 38.

- Șomâcu, Cornel (23 April 2015). "Înființarea armatei pământene în zorii secolului al XIX-lea" (in Romanian).

- Maravela, Petre (30 June 2015). "Istoricul Brăilei – Episodul X". braila-portal.ro (in Romanian).

- Cornel I., Scafeș (2012). "Înzestrarea oștirilor române în vremea Regulamentului Organic (1830-1856)" (PDF). Buletinul Arhivelor Militare Române (in Romanian). No. 57/2012. pp. 21–23. ISSN 1454-0924.

- d'Ohsson, Constantin Mouradgea (2006). Histoire des Mongols depuis Tchinguiz-Khan jusqu'à Timour Bey ou Tamerlan (in French). Vol. II. Elibron Classics. pp. 627–628. ISBN 0543942430.

- Georgescu, Vlad (1991). The Romanians: A History. Ohio State University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0814205119.

- Vásáry 2005, p. 112.

- Bárány, Attila (2012). "The Expansion of the Kingdom of Hungary in the Middle Ages (1000–1490)". In Berend, Nóra (ed.). The Expansion of Central Europe in the Middle Ages. Ashgate Variorum. p. 87. ISBN 9781409422457.

- Vásáry 2005, p. 154.

- Rezachevici 2004, p. 168–169.

- Rezachevici 2004, pp. 170–171.

- Kristó, Gyula (1988). Az Anjou-kor háborúi [Wars in the Age of the Angevins] (in Hungarian). Zrínyi Kiadó. pp. 157–159. ISBN 9633269059.

- Medin, Antonio; Tolomei, Guido (1900). Cronaca Carrarese. Rerum italicarum scriptores. Vol. 17. Città di Castello: S. Lapi. p. 145. OCLC 1050258472.

- (in Romanian) Constantin C. Giurescu, Istoria Românilor, vol. I, Bucharest, 1938, p. 367

- Stoica, Vasile (1919). The Roumanian Question: The Roumanians and their Lands. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Printing Company. p. 16.

- Cîmpeanu 2022, p. 181.

- Whelan, Mark (January 2016). "Pasquale de Sorgo and the Second Battle of Kosovo (1448): A Translation". The Slavonic and East European Review. Modern Humanities Research Association. 94: 142.

- Neagoe 2019, pp. 155–156.

- Pogăciaș 2020, p. 24.

- Neagoe 2019, pp. 157.

- Pogăciaș 2020, p. 16.

- Gheorghe et al. 2019, pp. 127–128.

- Solly, Meilan (18 June 2019). "Trove of Cannonballs Likely Used by Vlad the Impaler Found in Bulgaria". Smithsonian magazine.

- Pogăciaș 2020, p. 18.

- Zuzeac, Dănuț (17 August 2016). "Povestea lui Radu de la Afumați, domnitorul celor 20 de războaie". Adevărul (in Romanian).

- Stoicescu, Nicolae (1983). Radu de la Afumați (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Militară. pp. 42–46.

- Gheonea, Valentin (September 1996). "Un domnitor controversat — Radu Paisie". Magazin Istoric (in Romanian). p. 51.

- "Tunurile și apeductul lui Petru Cercel". jurnaldedambovita.ro (in Romanian). 27 September 2018.

- Denize, Eugen (2002). Italia și italienii in cultura română (in Romanian). Editura Mica Valahie. p. 40. ISBN 9738511771.

- Boriga et al. 2012, p. 11.

- Pogăciaș, Andrei. "Campaniile lui Mihai Viteazul". Historia (in Romanian). Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- Panaitescu, Petre P. (2002). Mihai Viteazul (PDF) (in Romanian). Corint. ISBN 9736531732.

- Mugnai & Flaherty 2015, p. 58.

- Mugnai & Flaherty 2015, p. 59–60.

- Bâgiu, Lucian Vasile (2013). The Image of the Romanians in the Travelling Impressions of 17th Century Scandinavians (PDF). Editura Alfa. p. 389. ISBN 9786065401297.

- Speteanu, Viorel Gh. (4 September 2020). "1655 Razboiul seimenilor". independentaromana.ro (in Romanian).

- Pogăciaș 2016, p. 40.

- Pogăciaș 2016, p. 47.

- Pogăciaș, Andrei (2011). "Războiul ruso-austro-turc din 1736-39". Identitate și alteritate: Studii de istorie politică și cultură (in Romanian). Vol. 5. Cluj-Napoca: Presa Universitară Clujeană. pp. 339–348. ISBN 9789735953263 – via Academia.edu.

- Pogăciaș, Andrei (June 2021). "Nicolae Mavrogheni, de la dragoman la damnation memorie". Historia (in Romanian). No. 233/2021. pp. 22–24. ISSN 1582-7968.

- Pogăciaș 2016, p. 44–45.

- "Revoluția de la 1848, 170 de ani: Lupta din Dealul Spirii încheie Revoluția din Țara Românească". Agerpres (in Romanian). 13 September 2018.

- Ilie, Aurora-Florentina (2015). "Drapelul Regimentului 19 Infanterie, model 1922" (PDF). Anuarul Muzeului Național al Literaturii Române Iași (in Romanian). Iași: Editura Muzeelor Literare. p. 129.

- Ciachir 1965, p. 198–201.

- Cîmpeanu, Liviu (2018). "Considerații asupra artileriei lui Ștefan cel Mare". Analele Putnei (in Romanian). Centrul de cercetare și documentare Ștefan cel Mare (XIV): 323.

- Cîmpeanu 2022, p. 183.

- Eudoxiu Hurmuzachi; Nicolae Iorga (1911). Documente privitore la istoria românilor (in Romanian). Vol. 15: Acte și scrisori din arhivele orașelor ardelene 1358-1600. Bucharest: Atelierele Grafice Socec Comp. p. 256.

- Neagoe 2019, p. 155.

- "steag". DEXonline.

- "ceată". DEXonline.

- "pâlc". DEXonline.

- Pogăciaș 2016, p. 42.

- Pogăciaș 2016, p. 41.

- Pogăciaș 2016, p. 43.

- "panțîr". DEXonline.

- Neagoe 2019, p. 156.

- Stoicescu, Nicolae (1968). Curteni și slujitori. Contribuții la istoria armatei române (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Militară. p. 23. OCLC 641604285.

- Cîmpeanu 2022, p. 173.

- "Nave românești uitate: luntrea monoxilă". rnhs.info (in Romanian). 2021-06-11.

- Georgescu, Alexandra (15 March 2016). "Flota magistrală a lui Mihai Viteazul. Cum au distrus navele voievodului traficul otoman de provizii pe Dunăre". Adevărul (in Romanian).

- "Nave românești uitate: caicul și șaica". rnhs.info (in Romanian). 2021-03-13.

Bibliography

- Boriga, Gabriel Florin; Moțoc, Honorius; Stan, Mihai; Coandă, George; Petrescu, Victor; Boriga, Niculae Alexandru (2012). Enciclopedia orașului Târgoviște (PDF). Târgoviște: Bibliotheca. ISBN 9789737126795. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2023.

- Ciachir, Nicolae (1965). "Unele aspecte privind orașul București în timpul Războiului Crimeii (1853-1856)". București - Materiale de Istorie și Muzeografie (in Romanian). Bucharest: Muzeul de Istorie a orașului București.

- Cîmpeanu, Liviu (2022). Cruciada împotriva lui Ștefan cel Mare: Codrii Cosminului 1497 (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Humanitas. ISBN 9789735077198.

- Gheorghe, Adrian; Weber, Albert; Bohn, Thomas M.; Paulus, Cristof; Anca, Alexandru Ștefan (2019). Corpus Draculianum (in Romanian). Vol. 1: Scrisori și documente de cancelarie : cancelarii valahe. Brăila: Editura Academiei Române: Editura Istros a Muzuelui Brăilei. ISBN 9786066543842.

- Mugnai, Bruno; Flaherty, Chris (2015). Der lange Türkenkrieg : 1593 - 1606. Soldiers & weapons. Vol. II. Soldiershop Publishing. OCLC 1159296854.

- Neagoe, Claudiu (2019). "Military organization of Wallachia from the first Basarabs until the beginning of the 16th century". Annales d'Université "Valahia" Târgoviște. 21. ISSN 1584-1855 – via Persee.fr.

- Pogăciaș, Andrei (March 2016). "Armatele uitate. Trupele Țărilor Române în lungul secol fanariot". Historia Special (in Romanian). No. 14/2016. ISSN 2286-0258.

- Pogăciaș, Andrei (May 2020). "Campaniile militare ale lui Vlad Țepeș". Historia (in Romanian). No. 220/2020. ISSN 1582-7968.

- Rezachevici, Constantin (2004). "Caracterul bătăliei din 1330 între Basarab și Carol Robert: Țărani neînarmați sau cavaleri de tip apusean?". Argesis – Studii și Comunicări [The character of the 1330 battle between Basarab and Carol Robert: Unarmed peasants or Western-style knights?]. Pitești: Muzeul Județean Argeș.

- Vásáry, István (2005). Cumans and Tatars: Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521837561.