Culture of Wallis and Futuna

Wallis and Futuna, an overseas territory of France in Oceania, has a rich Polynesian culture that is very similar to the cultures of its neighbouring nations Samoa and Tonga. The Wallisian and Futunan cultures share very similar components in language, dance, cuisine and modes of celebration.

Fishing and agriculture are the traditional practices and most people live in traditional fate houses in an oval shape made of thatch.[1] Kava, as with many Polynesian islands, is a popular beverage brewed in the two islands, and is a traditional offering in rituals.[1] Highly detailed tapa cloth art is a specialty of Wallis and Futuna.[2]

Language and religion

The native languages spoken daily by the islanders are Wallisian (also called ʻUvea) and Futunan, two closely related languages which trace their roots to Samoic origin. Despite this, the official language (because of its administrative purposes), the de jure language is French (with the population of each island preferring to talk in their own native tongue).[3] Oral traditions include the Tongan presence on Uvea and the Chant of Lausikula.[4]

Most of the people are Roman Catholic;[5] the law of Wallis and Futuna is partially based on Catholic morals.[6] The Patron Saint of the Islands, Pierre Chanel was the first missionary who came to the island in 1837.[1]

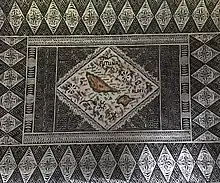

Art

Tapa is a popular art form which is made from the "base" of the bark of the mulberry and breadfruit trees. The pounded bark is painted with vegetable colours and with attractive designs. It provides employment to about 300 people in almost every village, and from which many families have been economically benefited in the two islands. This art form is in great demand in the Pacific, in the Noumea and Tahiti. Another art form is making of mats and necklaces with straw and shells. Efforts to further promote this vocation to export goods beyond the islands to Europe and France has faced problems of high transportation costs.[1]

Music

The music of Wallis and Futuna is mainly Polynesian. Idiophones and aerophones are used exclusively; examples of these include slit-gongs (lali), stamping tubes, sticks, rolled mats (fala), sounding boards (lolongo papa), body percussion, Jew's harps (utete), flutes, shell trumpets, and leaf oboes.[7]

Festivals and dance

Numerous festivals are celebrated in Wallis and Futuna throughout the year; on St Chanel Day, pigs are roasted and placed in the sun, and dancing performances are held. The Wallis and Futuna Festival is put on in Noumea annually.[8] Flae fones are community feasting and meeting structures.[9]

The people of Wallis and Futuna are stated to be "excellent dancers".[10] There are at least 16 types of dances (faive), their differences based upon location, occasion, number of dancers, gender, accompanying instruments, and other modifiers. Most dances are accompanied by singing and some type of percussion instruments as dancing without drumming is considered unusual. The kailao (paddle-club dance), however, has no song and only includes percussion.[11] Wallis and Futuna dancers perform across the Oceania region at festivals.[12]

Uvea Museum Association holds the first 16mm colour film of dance on Wallis in its collections, which was recorded in 1943.[13]

Food and beverage

Kava is the indigenous Polynesian beverage which is customarily served in all religious rituals. Kava is brewed in a wooden vessel known as a tana, a multilegged bowl which is also an art form carved in wood, that is much in demand.[1] Australian beer is also popular. Diet includes chicken, coconuts, figs, mangoes, pandanus, pork, and wild cherry.

Tourism

There is not much tourism in the two islands. The natural heritage of the territory is largely preserved; there are not many recreational sites in Wallis and Futuna. Some of the cultural heritages that attract tourists are the grave of Saint Pierre Chanel who was canonized in 1954 and other natural attractions of lakes, lagoons and beaches, and sports activities such as golfing (6 hole course in Wallis), diving and flying.[1] Uvea Museum Association is a military museum dedicated to preserving the history of the Second World War in the territory.[13]

Traditional monarchies and their role

Wallis and Futuna is an overseas collectivity of the French Republic. The collectivity is made up of three traditional kingdoms: ʻUvea, on the island of Wallis, Sigave, on the western part of the island of Futuna, and Alo, on the island of Alofi and on the eastern part of the island of Futuna. The current King of Uvea is Kapiliele Faupala and the current King of Sigave is Visesio Moeliku. They have reigned since 2008 and 2004, respectively. The king of Alo is Petelo Sea who is crowned in 2014. The three Kings are part of the government of the overseas collectivity.

References

- Wallis & Futuna Business Law Handbook: Strategic Information and Laws. Int'l Business Publications. 1 January 2012. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-1-4387-7141-0. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- Hinz, Earl R.; Howard, Jim (2006). Landfalls of Paradise: Cruising Guide to the Pacific Islands. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 220–. ISBN 978-0-8248-3037-3.

- "Wallis and Futuna: Culture".

- Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (15 April 1999). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts, Languages and Texts. Taylor & Francis. pp. 333–. ISBN 978-0-203-20290-6.

- Jensen, Lars (2008). A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures: Continental Europe and Its Empires. Edinburgh University Press. p. 140. ISBN 9780748623945.

- Aldrich, Robert; Connell, John (2006). France's Overseas Frontier. Cambridge University Press. p. 180. ISBN 9780521030366.

- McLean, p. 219

- Beran, Harry; Arthur, Tom; Chrisp, Rebecca (1998). Oceanic and Indonesian art: collector's choice : an exhibition of 102 works from 90 private Australian collections at Nomadic Rug Trader, Sydney, 18 July to 14 August 1998. Oceanic Art Society in association with Crawford House. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-86333-162-3. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- Price, Theron Douglas; Feinman, Gary M. (2010). Pathways to Power: Archaeological Perspectives on Inequality, Dominance, and Explanation. Springer. pp. 122–. ISBN 978-1-4419-6300-0.

- Ridgell, Reilly (1995). Pacific Nations and Territories: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia (3 ed.). Bess Press. p. 153. ISBN 9781573060011.

- McLean, Mervyn (1999). Weavers of Songs: Polynesian Music and Dance. Auckland University Press. pp. 223–. ISBN 978-1-86940-212-9.

- Dils, Ann; Albright, Ann Cooper (19 October 2001). Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader. Wesleyan University Press. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-8195-6413-9. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- Mayer, Raymond; Nau, Malino; Pambrun, Eric; Laurent, Christophe (2006). "Chanter la guerre à Wallis ('Uvea)". Journal de la Société des Océanistes (in French) (122–123): 153–171. doi:10.4000/jso.614.