Journeyman years

In a certain tradition, the journeyman years (Wanderjahre) are a time of travel for several years after completing apprenticeship as a craftsman.[1] The tradition dates back to medieval times and is still alive in France, Scandinavia[2] and the German-speaking countries.[3] Normally three years and one day is the minimum period of journeyman. Crafts include roofing, metalworking, woodcarving, carpentry and joinery, and even millinery and musical instrument making/organ building.

In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, when the guild system still controlled professions in the visual arts, the wanderjahre was taken by painters, mason-architects and goldsmiths, and was highly important for the transmission of artistic style around Europe. The development of late modern nations and their borders within Europe did not have much effect until the 19th century.

Historic roots

.jpg.webp)

In medieval times the apprentice was bound to his master for a number of years. He lived with the master as a member of the household, receiving most or all of his compensation in the form of food and lodging; in Germany an apprentice normally had to pay a fee (German: Lehrgeld) for his apprenticeship. After the years of apprenticeship (Lehrjahre) the apprentice was absolved from his obligations (this absolution was known as a Freisprechung). The guilds, however, would not allow a young craftsman without experience to be promoted to master—they could only choose to be employed, but many chose instead to roam about.[4]

Until craftsmen became masters, they would only be paid by the day (the French word journée refers to the time span of a day). In parts of Europe, such as in later medieval Germany, spending time as a journeyman (Geselle), moving from one town to another to gain experience of different workshops, became an important part of the training of an aspirant master.[5] Carpenters in Germany have retained the tradition of travelling journeymen even today, although only a small minority still practice it.

In the Middle Ages, the number of years spent journeying differed according to the craft. Only after half of the required journeyman years (Wanderjahre) would the craftsman register with a guild for the right to be an apprentice master. After completing the journeyman years, he would settle in a workshop of the guild and after toughing it out for several more years (Mutjahre), he would be allowed to produce a "masterpiece" (German: Meisterstück) and to present it to the guild. With their consent he would be promoted to guild master and as such be allowed to open his own guild workshop in town.

The development of social-contract theories resulted in a system of subscriptions and certificates. When arriving in a new town the journeyman would be pointed to a survey master (Umschaumeister) or to a survey companion (Umschaugeselle). He would be given a list of workshops to present himself to find work (Umschau literally means "look-around"). When not succeeding the journeyman would be given a small amount of money (Zehrgeld) - enough to sustain his travel to the next town. Otherwise he would get a place in a guild shelter (Gesellenherberge). His name would be added to the guild chest (Zunftlade) along with a declaration of how long he would be bound to the master, usually for half a year. Both sides could recall that subscription (Einschreibung) at any time. The subscription of a new companion commonly became the occasion of a big carousal among the other bound journeymen in town.

When leaving the town the guild would hand over a certificate (Kundschaft) telling of the work achievements along with asserting the journeyman's proper conduct and the orderly ending of the subscription. It was hard to find a new subscription in the next town without it, but in reality, masters did often complain about journeymen running away. Many guild shelters had a black board telling the names of such absconders - along with the debts they had left behind. The certificates were hand-written until about 1730, when printed forms evolved with places to fill in details. By about 1770 the forms started to carry a copperplate print of the cityscape. The certificates were often large and unhandy, so that smaller travelling books replaced them by about 1820. This practice coincided with the establishment of modern police in Europe after the coalition wars (1803-1815) against Napoleon. The guild chest was replaced by state offices to keep registers. In some places the guilds were even banned from maintaining registers.

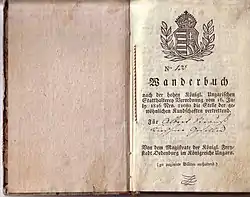

Travelling book of a German furrier named Albert Strauß in the Kingdom of Hungary of the Habsburg Monarchy in the year 1816.

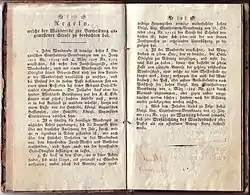

Travelling book of a German furrier named Albert Strauß in the Kingdom of Hungary of the Habsburg Monarchy in the year 1816. A travelling book of Albert Strauß: Regeln, welche der Wandernde zur Vermeidung angemessener Strafe zu beobachten hat. ("Rules, which the journeyman has to observe to avoid proper punishment").

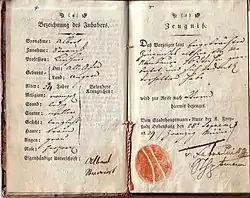

A travelling book of Albert Strauß: Regeln, welche der Wandernde zur Vermeidung angemessener Strafe zu beobachten hat. ("Rules, which the journeyman has to observe to avoid proper punishment"). A travelling book of Albert Strauß: Bezeichnung des Inhabers ("description of the owner").

A travelling book of Albert Strauß: Bezeichnung des Inhabers ("description of the owner").

Sociologically, one may see the Wanderjahre as recapitulating a nomadic phase of human societal development.[6] See also Rumspringa.

Germany

The tradition of the journeyman years (auf der Walz sein) persisted well into the 1920s in German-speaking countries, but was set back by multiple events like Nazis allegedly banning the tradition, the postwar German economic boom making it seem to be too much of a burden, and in East Germany the lack of opportunities for work in an economic system based on Volkseigener Betrieb. Beginning in the late 1980s, renewed interest in tradition in general together with economic changes (especially after the fall of the Berlin Wall) have caused the tradition to gain wider acceptance. The tradition was brought back to life mostly unchanged from the medieval concept since the journeyman brotherhoods (Schächte) never ceased to exist. (including a Confederation of European Journeymen Associations).

The journeyman brotherhoods had established a standard to ensure that wandering journeymen are not mistaken for tramps and vagabonds. The journeyman is required to be unmarried, childless and debt-free—so that the journeyman years will not be taken as a chance to run away from social obligations. In modern times the brotherhoods often require a police clearance. Additionally, journeymen are required to wear a specific uniform (Kluft) and to present themselves in a clean and friendly manner in public. This helps them to find shelter for the night and a ride to the next town.

A travelling book (Wanderbuch) was given to the journeyman and in each new town, he would go to the town office asking for a stamp. This qualifies both as a record of his journey and also replaces the residence registration that would otherwise be required. In contemporary brotherhoods, the "Walz" is required to last at least three years and one day (sometimes two years and one day). During the journeyman years the wanderer is not allowed to return within a perimeter of 50 km of his home town, except in specific emergency situations, such as the impending death of an immediate relative (parents and siblings).

At the beginning of the journey, the wanderer takes only a small, fixed sum of money with him (exactly five Deutsche Marks was common, now five euros); at its end, he should come home with exactly the same sum of money in his pocket. Thus, he is supposed neither to squander money nor to store up any riches during the journey, which should be undertaken only for the experience.

There are secret signs, such as specific, involved handshakes, that German carpenters traditionally use to identify each other. They are taught to the beginning journeyman before he leaves. This is another traditional method to protect the trade against impostors. While less necessary in an age of telephones, identity cards and official diplomas, the signs are still retained as a tradition. Teaching them to anybody who has not successfully completed a carpenter apprenticeship is still considered very wrong, even though it is no longer a punishable crime today.

As of 2005, there were 600 to 800 journeymen "on the Walz", either associated with a brotherhood or running free. While the great majority are still male, young women are no longer unheard of on the Walz today.

Journeyman uniform in Germany

Journeymen can be easily recognised on the street by their clothing. The carpenter's black hat has a broad brim; some professions use a black stovepipe hat or a cocked hat. The carpenters wear black bell-bottoms and a waistcoat and carry the Stenz, which is a traditional curled hiking pole. Since many professions have since converted to the uniform of the carpenters, many people in Germany believe that only carpenters go journeying, which is untrue – since the carpenter's uniform is best known and well received, it simply eases the journey.

The uniform is completed with a golden earring and golden bracelets—which could be sold in hard times and in the Middle Ages could be used to pay the gravedigger if any wanderer should die on his journey. The journeyman carried his belongings in a leather backpack called the Felleisen, but some medieval towns, Charlottenburg probably having been the first and there, in particular, the temporary homes dedicated to house journeymen, banned those (for the fleas in them) so that most journeyman started to make use of a coarse cloth thus called Charlottenburger (abbreviated to "Charlie") to wrap up their belongings.

Journeymen in Århus, Denmark

Journeymen in Århus, Denmark Journeymen in Bad Kissingen (2010)

Journeymen in Bad Kissingen (2010) Journeymen (2011)

Journeymen (2011)

Reception in society

While the institution of the journeyman years is original to craftsmen, the concept has spread to other professions. As such, a priest could set out on an extended journey to do research in the libraries of monasteries across Europe and gain wider knowledge and experience.

The traveler books or Wanderbücher are an important research source that show migration paths in the early period of industrialisation in Europe. Journeymen's paths often show boundaries of language and religion that hindered travel of craftsmen "on the Walz".

Journeyman years in the arts

- The Australian song "Waltzing Matilda" is based on the journeyman's "Walz".[7]

- There are many wanderer songs based on the "Walz" experience.

- Gustav Mahler composed Songs of a wandering apprentice

- Goethe's novel Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre (Wilhelm Meister's Journeyman Years)

- Schubert's song cycle "Die Schöne Müllerin" is about an apprentice miller and how he fared at a mill where he stays to work and falls in love with the miller's daughter.

- Reinhard Mey's song "Drei Jahre und ein Tag" is about the wandering of the Journeyman years.

- In the videogame Pentiment the main character, Andreas, is finishing his wanderjahre as the game begins.

Well-known journeymen

The following people are known to have completed the traditional journeyman years:

- August Bebel (turner) – founder of the Social Democratic Party of Germany

- Jakob Böhme (shoemaker) – mystic and Christian philosopher

- Albrecht Dürer (painter) – German copperplate engraver and painter, later famous artist

- Friedrich Ebert (saddlemaker) – first president of the Weimar Republic

- Adam Opel (mechanic) – maker of sewing machines and bicycles. In the following generation his firm became known for car making

- Wilhelm Pieck (carpenter) – first president of the GDR

See also

References

- Tomas Munita (August 7, 2017). "Cleaving to the Medieval, Journeymen Ply Their Trades in Europe". New York Times.

- Sara Pagh Kofoed (August 11, 2020). "22-årige Jens skal tre år på landevejen". DR_(broadcaster).

- Spiegel Online International 05/17/2006 "Craftsmen Awandering"

- Sir Robert Harry Inglis Palgrave (1896). Dictionary of political economy. Macmillan and co. p. 491. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- Sabine Baring-Gould (1910). Family names and their story. Seeley & Co., Limited. pp. 127–8. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

-

Compare:

Chénetier, Marc, ed. (1986). Critical angles: European views of contemporary American literature. Crosscurrents (Carbondale). Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 89. ISBN 9780809312160. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

[...] an aristocratic tradition ("wanderjahr" [...]) that could lead to a nomadic life [...].

- Harry Hastings Pearce (1971). On the origins of Waltzing Matilda (expression, lyric, melody). Hawthorn Press. p. 13. Retrieved 27 December 2011.