Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan

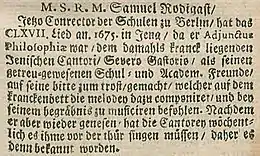

"Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan" (What God Ordains Is Always Good) is a Lutheran hymn written by the pietist German poet and schoolmaster Samuel Rodigast in 1675. The melody has been attributed to the cantor Severus Gastorius. An earlier hymn with the same title was written in the first half of the seventeenth century by the theologian Michael Altenburg.

History

As described in Geck (2006), an apocryphal account in the 1687 Nordhausen Gesangbuch (Nordhausen songbook) records that the hymn text was written by Samuel Rodigast in 1675 while his friend, the cantor Severus Gastorius, whom he knew from school and university, was "seriously ill" and confined to his bed in Jena. The account credits Gastorius, believing himself to be on his death bed, with composing the hymn melody as music for his funeral. When Gastorius recovered, he instructed his choir in Jena to sing the hymn each week "at his front door ... to make it better known."[1][2]

Rodigast studied first at the Gymnasium in Weimar and then at the University of Jena, where from 1676 he held an adjunct position in philosophy. In 1680 Rodigast was appointed vice-rector of the Gymnasium zum Grauen Kloster in Berlin, eventually becoming rector in 1698. In the interim he had refused offers of a professorship at Jena and school rectorships elsewhere.[3]

He was closely associated with the founder and leader of the pietist movement, Philipp Jakob Spener, who moved to Berlin in 1691 and remained there until his death in 1705.[3][4][5]

In his 1721 book on the lives of famous lyric poets, Johann Caspar Wetzel reports that already by 1708 Rodigast's hymn had acquired the reputation as a "hymnus suavissimus & per universam fere Evangelicorum ecclesiam notissimus," i.e. as one of the most beautiful and widely known church hymns.[6][7] The text of the hymn was first published without melody in Göttingen in 1676 in an appendix to the Hannoverische Gesangbuch (Hanover songbook). It was published with the melody in 1690 in the Nürnbergische Gesangbuch (Nuremberg songbook).[8]

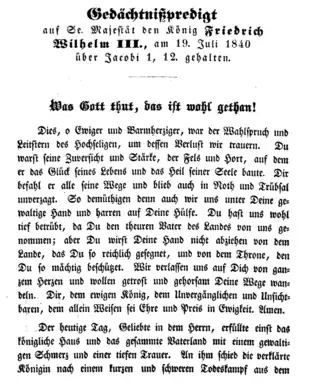

Rodigast's involvement with pietism is reflected in the hymn "Was Gott tut, das ist wohgetan", which is considered to be one of the earliest examples of a pietist hymn. The Encyclopedia Britannica describes it as "one of the most exquisite strains of pious resignation ever written."[6][9] The opening phrase, "Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan", is a variant of "Alles, was er tut, das ist recht," Luther's German version of "all His ways are just" from Deuteronomy 32:4.[10] The theme of the hymn is pious trust in God's will in times of adversity and tribulation: as Unger writes, "True piety is to renounce self and submit in quiet faith to God's providential acts despite suffering and poverty."[11] In the 1690 Nürnbergische Gesangbuch the hymn is listed under Klag- und Creuz- Lieder (hymns of mourning and the Cross).

Despite the "sick-bed" narrative surrounding the composition of the hymn melody, there has been uncertainty as to whether Gastorius was involved in composing the original melody. On the other hand, it is known that the melody of the first half is the same as that of the hymn "Frisch auf, mein Geist, sei wohlgemuth" by Werner Fabricius (1633–1679), published by Ernst Christoph Homburg in Naumburg in 1659 in the collection Geistliche Lieder.[8][12]

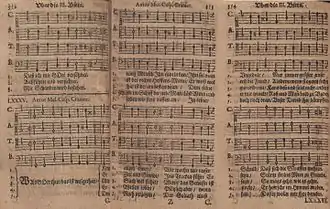

Although the text of Rodigast's hymn was published without the melody in 1676 (in the Hannoverische Gesangbuch), it was discovered in the 1960s that already within three years the melody had been used in Jena for other hymn texts by Daniel Klesch. Educated at the University of Wittenberg, Klesch was a Hungarian pietist minister who, after the Protestant expulsions in Hungary, served during 1676–1682 as rector at the Raths-Schule in Jena where Gastorius acted as cantor. Klesch used the melody for two different hymn texts—"Brich an, verlangtes Morgenlicht" and "Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich"—in the Andächtige Elends-Stimme published by his brother Christoph Klesch in 1679. The Klesch hymnbook names four of the 44 hymn melodies it contains as being known and two as being composed by a king and a count; it describes the remaining 38—without further precision—as being written by Severus Gastorius and Johann Hancken, cantor in Strehlen in Silesia.[14][15][16][17]

The text and melody of Rodigast's hymn were published together for the first time in 1690 in the Nürnbergische Gesangbuch, with the composer marked as "anonymous". Before that the melody with the hymn title had already been used by Pachelbel for an organ partita in 1683. Taking into account the appearance of the melody in the Klesch hymnbook and the history of the hymn given in the 1687 Nordhausen Gesangbuch, the Swiss theologian and musicologist Andreas Marti has suggested that it is plausible that, as he lay on his sick-bed in Jena, the cantor Severus Gastorius had the melody of Fabricius spinning around in his head as an "earworm" and was inspired to add a second half.[8][18]

In German-speaking countries, the hymn appears in the Protestant hymnal Evangelisches Gesangbuch as EG 372[19] and in the Catholic hymnal Gotteslob as GL 416.[20]

Precursor to hymn

There was a precursor of Rodigast's hymn with the same title to a text by the theologian Michael Altenburg,[7] first published in 1635 by the Nordhausen printer Johannes Erasmus Hynitzsch, with first verse as follows:

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan,

Kein einig Mensch ihn tadeln kann,

Ihn soll man allzeit ehren.

Wir mach'n mit unser Ungedult

Nur immer größer unser Schuld

Dass sich die Strafen mehren.

Like its sequel, each of the seven verses starts with the same incipit. The hymn was published in the 1648 Cantionale Sacrum, Gotha, to a melody of Caspar Cramer, first published in Erfurt in 1641. It is No. 2524 in the German hymn catalogue of Johannes Zahn.[21][22][23]

In 1650 Samuel Scheidt composed a four part chorale prelude SSWV 536 on Altenburg's hymn in his Görlitzer Tabulaturbuch.[24]

Text

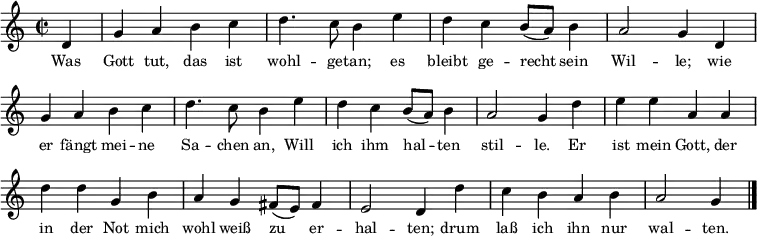

In the original German, the hymn has six stanzas, all beginning with the incipit "Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan". Below are the first, fifth and last stanzas with the 1865 translation by Catherine Winkworth.[8]

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan!

Es bleibt gerecht sein Wille;

Wie er fängt meine Sachen an,

Will ich ihm halten stille.

Er ist mein Gott, der in der Not

Mich wohl weiß zu erhalten,

Drum laß' ich ihn nur walten.

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan!

Muß ich den Kelch gleich schmecken,

Der bitter ist nach meinem Wahn,

Laß' ich mich doch nicht schrecken,

Weil doch zuletzt ich werd' ergötzt

Mit süßem Trost im Herzen,

Da weichen alle Schmerzen.

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan!

Dabei will ich verbleiben;

Es mag mich auf die rauhe Bahn

Not, Tod und Elend treiben,

So wird Gott mich ganz väterlich

In seinen Armen halten,

Drum laß' ich ihn nur walten.

Whate'er my God ordains is right,

Holy His will abideth;

I will be still whate'er He doth,

And follow where He guideth.

He is my God, though dark my road,

He holds me that I shall not fall:

Wherefore to Him I leave it all.

Whate'er my God ordains is right

Though now this cup, in drinking,

May bitter seem to my faint heart,

I take it, all unshrinking.

My God is true; each morn anew

Sweet comfort yet shall fill my heart,

And pain and sorrow shall depart.

Whate'er my God ordains is right:

Here shall my stand be taken;

Though sorrow, need, or death be mine,

Yet I am not forsaken.

My Father's care is round me there;

He holds me that I shall not fall:

And so to Him I leave it all.

Melody

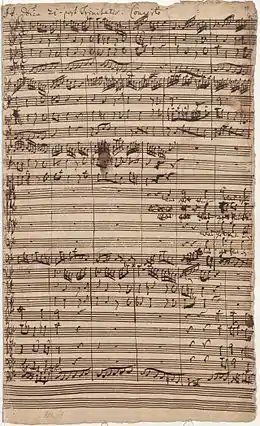

First stanza and melody in 2/2 time as they appear in the 1690 Nürnbergische Gesangbuch.[25][12][26][8][27]

Musical settings

Rodigast's hymn and its melody have been set by many composers, one of the earliest being Pachelbel, who set it first, together with other hymn, in an organ partita Musicalische Sterbens-Gedancken (Musical thoughts on dying), published in Erfurt in 1683. The organ partita, originating "in the devastating experience of the death of Pachelbel's family members during the plague in Erfurt", reflects the use of "Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan" as a funeral hymn. He set the hymn later as a cantata, most likely in Nürnberg after 1695.[18][28]

Johann Sebastian Bach set the hymn several times in his cantatas: cantatas BWV 98, BWV 99 and BWV 100 take the name of the hymn, the last setting all six stanzas; while cantatas BWV 12, BWV 69 and BWV 144 include a chorale to the words of the first or last stanza;[26][29] and he set the first stanza as the first in the set of three wedding chorales BWV 250–252, for SATB, oboes, horns, strings and organ, intended for use in a wedding service instead of a longer cantata.[30] For his inaugural cantata in Leipzig in 1723, Die Elenden sollen essen, BWV 75, Bach chose chorales on the fifth and last verses to end the two parts. Referring to contemporary disputes between orthodox Lutherans and Pietists, Geck (2006) has suggested that Bach's choice of a popular "spiritual" pietist hymn instead of a "traditional" Lutheran chorale might have been considered controversial. Indeed, before being appointed as Thomaskantor, Bach had been required by the Consistory in Leipzig to certify that he subscribed to the Formula of Accord, and thus adhered to the orthodox doctrines of Luther. Wolff (2001), however, comments that, from what is known, "Bach never let himself be drawn into the aggressive conflict between Kirchen- and Seelen-Music—traditional church music on the one hand and music for the soul on the other—which had a stifling effect on both sacred and secular musical life elsewhere in Germany."[6][31][32]

Bach also set the hymn early in his career for organ as the chorale prelude BWV 1116 in the Neumeister Collection. The hymn title appears twice on empty pages in the autograph manuscript of Orgelbüchlein, where Bach listed the planned chorale preludes for the collection: the 111th entry on page 127 was to be the hymn of Altenburg; and the 112th entry on the next page was for Rodigast's hymn.[33][26]

Amongst Bach's contemporaries, there are settings by Johann Gottfried Walther as a chorale prelude and Georg Philipp Telemann as a cantata (TWV 1:1747). Bach's immediate predecessor as Thomaskantor in Leipzig, Johann Kuhnau, also composed a cantata based on the hymn. In addition Christoph Graupner composed four cantatas on the text between 1713 and 1743; and Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel set the text in his cantata Was Gott tut das ist wohlgetan, H. 389. Amongst Bach's pupils, Johann Peter Kellner, Johann Ludwig Krebs and Johann Philipp Kirnberger composed chorale preludes on the melody.[27][34]

In the nineteenth century, Franz Liszt used the hymn in several compositions. In 1862, following the death of his daughter Blandine, he wrote his Variations on a theme of J. S. Bach, S180 for piano based on Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen, BWV 12, with its closing chorale on "Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan" on the penultimate page above which Liszt wrote the words of the chorale. Walker (1997) describes the Variations as "a wonderful vehicle for his grief" and the Lutheran chorale as "an unmistakable reference to the personal loss that he himself had suffered, and his acceptance of it."[35] The hymn also appeared as the sixth piece (for chorus and organ) in Liszt's Deutsche Kirchenlieder, S.669a (1878–1879) and the first piece in his Zwölf alte deutsche geistliche Weisen, S.50 (1878–1879) for piano. It was also set in the first of the chorale preludes, Op.93 by the French organist and composer Alexandre Guilmant.[27][35]

In 1902 Max Reger set the hymn as No. 44 in his collection of 52 Chorale Preludes, Op. 67. He also set it in 1914 as No. 16 of his 30 little chorale preludes for organ, Op. 135a.[36] In 1915 Reger moved to Jena, one year before his untimely death. In Jena he played the organ in the Stadtkirche St. Michael and composed his Seven Pieces for Organ, Op. 145. The first piece, Trauerode, is dedicated to the memory of those who fell in the war during 1914–1915: initially darkly coloured, the mood gradually changes to one of peaceful resignation at the close, when the chorale Was Gott tut is heard. The second piece is entitled Dankpsalm and is dedicated "to the German people". It begins with brilliant toccata-like writing which alternates with darker more contemplative music. The piece contains settings of two Lutheran chorales: first, another version of "Was Gott tut"; and then, at the conclusion, "Lobe den Herren". According to Anderson (2013), "the acceptance of divine will in the first is answered by praise of the omnipotent God in the second, a commentary on the sacrifice of war in a Job-like perspective."[37][38][39]

Sigfrid Karg-Elert included a setting in his 66 Chorale improvisations for organ, published in 1909.[40]

Notes

- Görisch & Marti 2011, p. 45 "bitte zum trost gemacht, welcher auf dem kranckenbett die melodey dazu componiert und bey seinem begräbnis zu musiciren befohlen

- For the life and works of Severus Gastorius, see:

- Julian 1892, digitised page

- Wallmann 1995.

- Heidemann 1874.

- Geck 2006

- Görisch & Marti 2011

- Terry 1917

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hymns". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 189.

- Görisch & Marti 2011, p. 46.

- Unger 1997.

- Zahn 1890b

- See:

- Detailed description, engraving of Jena, Caspar Merian, 1650

- Richter 1887, history of Raths-Schule until 1650

- Richter 1888, history of Raths-Schule after 1650

- Görisch & Marti 2011, p. 44.

- Fornaçon 1963, p. 167.

- Flood 2006.

- Wallmann 2011.

- Görisch & Marti 2011, p. 50

- Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan gesangbuch-online.de

- Gotteslobvideo GL 416 Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan katholisch.de

- Terry 1921

- Fischer & Tümpel 1905

- Zahn 1890a

- Scheidt 1941

- The hymn is No. 5629 in the catalogue of Johannes Zahn.

- Williams 2003

- Braatz & Oron 2008

- Rathey 2010.

- Dürr 2006

- Hudson 1968.

- Leaver 2007

- Wolff 2001

- Stinson 1999

- RISM listing, cantata Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan by Johan Kuhnau, Saxon State and University Library Dresden. This cantata is one of those scheduled for publication by the "Kuhnau-Project" in Leipzig, directed by Michael Maul.

- Walker 1997

- Reger 1914

- Anderson 2013.

- Haupt 1995.

- Anderson, Keith (2006), Max Reger's Organ Works, Volume 7: Symphonic Fantasia and Fugue • Seven Organ Pieces, Programme Notes, Naxos Records

- Choral-Improvisationen für Orgel, Op.65 (Karg-Elert, Sigfrid): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

References

- Anderson, Christopher S. (2013), "Max Reger (1873–1963)", in Christopher S. Anderson (ed.), Twentieth-Century Organ, Routledge, p. 107, ISBN 978-1136497902

- Braatz, Thomas; Oron, Aryeh (2008), "Chorale Melodies used in Bach's Vocal Works – Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan", Bach Cantatas Website, retrieved 29 January 2017

- Dürr, Alfred (2006), The cantatas of J. S. Bach, translated by Richard Douglas P. Jones, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-929776-2

- Fischer, Albert; Tümpel, Wilhelm (1905), Das Deutsche evangelische Kirchenlied des siebzehnten Jahrhunderts, Volume II (in German), pp. 42–43

- Flood, John L. (2006), "Daniel Klesch", Poets Laureate in the Holy Roman Empire: A Bio-bibliographical Handbook, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 1013–1014, ISBN 3110912740

- Fornaçon, Siegfried (1963), "Werke von Severus Gastorius", Jahrbuch für Liturgik und Hymnologie (in German), Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 8: 165–170, JSTOR 24192704

- Geck, Martin (2006), Johann Sebastian Bach: Life and Work, translated by John Hargraves, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 331–332, ISBN 0151006482

- Görisch, Reinhard; Marti, Andreas (2011), "Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan", in Herbst, Wolfgang; Seibt, Ilsabe (eds.), Liederkunde zum evangelischen Gesangbuch (in German), vol. 16 (1., neue Ausg. ed.), Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 44–51, ISBN 978-3525503027

- Haupt, Hartmut (1995), Orgeln in Ost- und Südthüringen, Arbeitshefte des Thüringischen Landesamtes für Denkmalpflege: Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, Thüringen, vol. 7, Ausbildung + Wissen, p. 168, ISBN 3927879592

- Heidemann, Julius (1874), Geschichte der grauen Klosters zu Berlin (in German), Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, pp. 180–190

- Hudson, Frederick (1968), "Bach's Wedding Music" (PDF), Current Musicology, The Music Department, Columbia University, 7: 110–120

- Jauernig, Reinhold (1963), "Severus Gastorius (1646–1682)", Jahrbuch für Liturgik und Hymnologie, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 8: 163–165, JSTOR 24192703

- Julian, John (1892), "Rodigast, Samuel", A Dictionary of Hymnology, vol. II, Scribner's Sons, p. 972

- Leaver, Robin (2007), Luther's Liturgical Music, Eerdmans Publishing, pp. 280–281, ISBN 978-0802832214

- Rathey, Markus (2002), "Severus Gastorius", in Ludwig Finscher (ed.), Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, Personenteil, vol. 7, Bärenreiter, pp. 602–603

- Rathey, Mark (2010), "Buxtehude and the Dance of Death: the chorale partita 'Auf meinen lieben Gott' (BuxWV 179) and the ars moriendi in the seventeenth century", Early Music History, 29: 161–188, doi:10.1017/S0261127910000124, S2CID 190683768

- Reger, Max (1914), Dreißig kleine Vorspiele zu den gebräuchlichsten Chorälen Op. 135a, Max-Reger-Institute, retrieved 3 February 2017

- Richter, Gustav (1887), "Das alte Gymnasium in Jena: Beiträge zu seiner Geschichte, I", Jahresbericht über das Gymnasium Carolo-Alexandrinum zu Jena

- Richter, Gustav (1888), "Das alte Gymnasium in Jena: Beiträge zu seiner Geschichte, II", Jahresbericht über das Gymnasium Carolo-Alexandrinum zu Jena

- Scheidt, Samuel (1941), Christhard Mahrenholz (ed.), Das Görlitzer Tabulaturbuch: vom Jahre 1650, Leipzig: C. F. Peters

- Stinson, Russell (1999), Bach: the Orgelbüchlein, Oxford University Press, pp. 3–10, ISBN 978-0-19-386214-2

- Terry, Charles Sanford (1917), Bach's Chorals, vol. II, Cambridge, The University Press, pp. 162–164, 561–562

- Terry, Charles Sanford (1921), Johann Sebastian Bach, Bach's Chorals, vol. 3 The Hymns and Hymn Melodies of the Organ Works, Cambridge University Press, p. 52

- Unger, Melvin P. (1997), "Bach's first two Leipzig cantatas: the question of meaning revisited", Bach, 28 (1/2): 87–125, JSTOR 41640435

- Wallmann, Johannes (1995), Theologie und Frömmigkeit im Zeitalter des Barock: gesammelte Aufsätze (in German), Mohr Siebeck, pp. 308–311, ISBN 316146351X

- Wallmann, Johannes (2011), "Der Pietismus an der Universität Jena", in Udo Strater (ed.), Pietismus und Neuzeit, vol. 37, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 36–65, ISBN 978-3525559093

- Walker, Alan (1997), Franz Liszt: The final years, 1861–1886, Cornell University Press, pp. 51–53, ISBN 0801484537

- Williams, Peter (2003), The Organ Music of J.S. Bach, Cambridge University Press, pp. 569–570

- Wolff, Christoph (2001), Johann Sebastian Bach: the learned musician, Oxford University Press, p. 114, ISBN 0-19-924884-2

- Zahn, Johannes (1890a), "2524", Die Melodien der deutschen evangelischen Kirchenlieder, vol. II, Verlag Bertelsmann, p. 130, archived from the original on February 4, 2017

- Zahn, Johannes (1890b), "5629", Die Melodien der deutschen evangelischen Kirchenlieder, vol. III, Verlag Bertelsmann, p. 478

External links

- Information about the tune on hymnary.org