Wealden Line

Wealden Line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Wealden Line[1] is a partly abandoned double track railway line in East Sussex and Kent that connected Lewes with Tunbridge Wells, a distance of 25.25 miles (40.64 km). The line takes its name from the Weald, the hilly landscape the lies between the North and South Downs.

The line is essentially composed of three sections: in the south, from Lewes to Uckfield closed on 4 May 1969; in the north, from Eridge to Tunbridge Wells West closed on 6 July 1985; in between, from Uckfield to Eridge remains open as part of the Oxted Line.

The northern section has partly re-opened under the auspices of the Spa Valley Railway, whilst the Lavender Line has revived Isfield Station on the southern section with about one mile of track. There has been a concerted campaign since 1986 led by the Wealden Line Campaign to have the whole line re-opened to passengers, but a 2008 study concluded that it would be "economically unviable".[2]

History

Authorisation

Authorisation for the construction of a line from Brighton to Hastings via Lewes was obtained by the Brighton, Uckfield & Tunbridge Wells Railway in 1844, sponsored by the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LBSCR), with the passing of the Brighton, Lewes and Hastings Railway Act (7 & 8 Vict. c. xci.). However, no works were commenced and another company, the Lewes and Uckfield Railway Company, was incorporated and secured on 27 July 1856 the passing of an Act to construct a line covering the 7.5 miles (12.1 km) to Uckfield from a point 1.5 miles (2.4 km) north of Lewes to be known as Uckfield Junction, on the LBSCR's Brighton to Hastings line.[3]

Attracted by the prospect of extra patronage on its coastal line, with which Lewes had been linked in 1846, the LBSCR supported the company's proposals and a connection linking Lewes to Uckfield was opened on 11 October 1858 to goods, with passengers one week later. The line, much of it through low-lying meadows, was easy to build and required only three minor cuttings and a number of bridges including one over the Ouse Navigation.[4] The initial service consisted of five trains each way on weekdays and three on Sundays. A four-horse coach service ran between Tunbridge Wells and Uckfield.[3]

Realignment

The LBSCR absorbed the Lewes and Uckfield Railway Company in 1864 and in the same year obtained authorisation to build a new line 3 miles (4.8 km) long running almost parallel with the East Coastway Line, which enabled the line from Uckfield to obtain independent access to Lewes without passing through the Lewes Tunnel. This struck out at a right angle from the Uckfield line about a quarter of a mile east of Hamsey, and approached Lewes from a northerly direction. Designed by the LBSCR's Chief Engineer Frederick Banister, it was more heavily engineered requiring embankments and bridges before joining the Brighton to Hastings line east of Lewes station. It enabled trains to be heading in the direction for Brighton, and obviated the need for locomotives to be turned. This section opened on 1 October 1868, part of the original connection to Uckfield Junction closing as a consequence.[5]

Extension to Tunbridge Wells West

The Lewes-Uckfield line was extended north by Banister to Eridge and Tunbridge Wells in 1868, ostensibly to counter a threat by the London, Chatham and Dover Railway, which had proposed a line from Beckenham to Brighton. The rights to construct this line had been granted to the Brighton, Uckfield & Tunbridge Wells Railway in 1861, but were purchased by the LBSCR before completion.[6]

Construction had already commenced in 1863 on the single track from Tunbridge Wells West to the new Groombridge Junction, and this was opened on 1 October 1866. The completion of the line south to Uckfield had to wait until 3 August 1868 due to the major structural work involved. Most notably, Banister had to oversee the construction of Rotherfield (later Crowborough) Tunnel (1,022 yards (935 m)) beneath the ridge of the Wealden Heights, and the Sleeches and Greenhurst viaducts between Crowborough and Buxted.[7] The LBSCR's desire to block any possible approach to Brighton even if this meant routing the line through areas with little traffic potential is shown by the provision of only three stations in the 12.25 miles (19.71 km) between Uckfield and Groombridge.[8]

The Sussex Advertiser reported on 5 August 1868 that the first train departed the LBSCR's station at Tunbridge Wells at 6.04 am for Uckfield, Lewes and Brighton with approximately 40 persons having booked tickets.[7]

Doubling and non-electrification

A single line link to the South Eastern Railway's Tunbridge Wells station was opened to passengers in 1876. The line from Uckfield was double tracked in 1894 and the completion of the Withyham spur between Ashurst and Birchden Junction enabled London services to run through to Uckfield or down the Cuckoo Line without reversing at Groombridge. However, little use was made until 1914.[9] The spur completed what was called the Outer Circle line, which provided an alternative route between Brighton and London via Oxted. The line was also the only subsidiary cross-country double line in East Sussex and, as it did not figure in Southern Railway's electrification programme in the 1930s, it was the last steam-operated line in the area.[10]

Route of the line

The line left Lewes immediately to the east of the station, curving sharply north for approximately 200 yards (180 m) on a short 1:60 gradient, crossing a girder bridge over goods lines and a second bridge over Cliffe High Street. Continuing on an embankment, Lewes Viaduct carried the line over the River Ouse. The river and its tributaries were crossed a further seven times before the line reached Uckfield. The line then turned north-west east of Hamsey village and followed the valley of the river, passing the signalbox at Culver Junction (3.25 miles (5.23 km)) where the line to Horsted Keynes and East Grinstead (now the Bluebell Railway) branched off, and rose gently to Barcombe Mills (3.75 miles (6.04 km)), originally Barcombe. This station was once popular with anglers, who descended in large numbers on the nearby River Ouse during bank holidays.[7]

The line continued to Isfield (5.75 miles (9.25 km)) before reaching Uckfield (8.5 miles (13.7 km)). The LBSCR had once planned to construct a further line through Uckfield, the Ouse Valley Railway, which would have connected Balcombe with Hailsham. The plan was abandoned in 1868 due to a lack of funds.[11]

Departing Uckfield, the line continues to Buxted (10¾ miles) and then passes over Greenhurst Viaduct (10 brick arches, 185 yards (169 m) (11.75 miles (18.91 km)), followed by Sleeches Viaduct (11 brick arches, 183 yards (167 m)) one mile further on. The line rises sharply on a 1:75 gradient and enters Crowborough Tunnel, which took its present name on 1 May 1897. Reaching Crowborough (Rotherfield until 1880, Crowborough until 1897, then Crowborough & Jarvis Brook) (15.25 miles (24.54 km)), the line reaches its highest point, more than 300 ft above sea level. Descending on a 1:75 gradient, it reaches Redgate Mill Junction (17.75 miles (28.57 km)) and then Eridge (19.25 miles (30.98 km)). At Birchden Junction (20 miles (32 km)), it heads east passing Groombridge Junction (20.75 miles (33.39 km)) and Groombridge (21.25 miles (34.20 km)), rising gradually to Tunbridge Wells West (25.25 miles (40.64 km)).[11]

The line's heyday

The line probably enjoyed its best and most popular period in the 1930s when regular services enabled passengers to travel from Brighton to Tonbridge, changing at Eridge for services from Eastbourne, with direct trains to London Bridge and London Victoria via East Croydon. There was also a daily through service linking with Brighton, Maidstone and Chatham in the east and Redhill and Reading in the west.[12]

Reduction of services was necessary during the Second World War, but many extras were run, including special non-stop "workmen's trains" which operated between London, Crowborough and Jarvis Brook and Mayfield.[13]

After the war passenger numbers were still rising, tempted by the frequent services and competitive prices. Even in 1969, travelling by rail was cheaper than going by bus: a return rail ticket from Barcombe Mills to Brighton cost 2 shillings, whilst the bus fare was 11d more expensive.[14]

Decline

In 1956 the British Railways, Southern Region moved to replace the complicated and inconsistent timetable with a regular hourly service, with additional trains at peak hours. Diesel-electric units appeared on the line in 1962, running to the steam timetable. The through service linking the Medway Towns to Brighton via Maidstone and Tonbridge was reduced to a Tonbridge to Brighton service.[9]

In 1964 a new timetable made travelling difficult by imposing long waits for connections: this policy of closure by stealth was a ploy to reduce passengers as British Railways was keen to close the section from Hurst Green to Lewes.[13]

In its last years of operation, the Uckfield to Lewes line saw an hourly off-peak service on weekdays, two-hourly on Sundays from Oxted to Lewes. During rush hours, the service was supplemented by trains from Victoria to Brighton via Hurst Green.

On Sunday, 23 February 1969, the last day of operation, the last trains left Lewes and Uckfield at 20.46 and 20.42 respectively. There was little public interest and no organised demonstrations took place to mark the occasion.

Closure

Lewes Relief Road

The future of the Lewes-Uckfield line was in doubt from 1964 when stage one of the Lewes Relief Road, a scheme to ease congestion in Lewes, was approved by the Conservative Minister of Transport Ernest Marples with a 75% grant towards the £350,000 costs.[15] This involved the construction of the Phoenix Causeway bridge to Cliffe High Street, the path of which was blocked by the embankment carrying the Lewes to Uckfield line. Were the railway to remain open, another road bridge or level crossing would be required at a cost of £135,000; East Sussex County Council was also against bridging the line on the grounds of "design and amenity".[16]

To facilitate the road scheme, the British Railways Board (BRB) agreed to close the Lewes-Uckfield line and to reactivate the 'Hamsey Loop', the previous alignment of the line abandoned in 1868 in favour of a more direct route, at the Council's expense if needed.[16] Approval for this plan was granted by section 4 of the British Railways Act 1966 which permitted:

A railway (1,586 yards in length) wholly in the parish of Hamsey in the rural district of Chailey commencing by a junction with the railway between Lewes and Cooksbridge at a point 365 yards south of Hamsey level crossing and terminating by a junction with the railway between Lewes and Eridge at a point 425 yards north-east of the bridge carrying last-mentioned railway over the river Ouse.[17]

The new route would cost £95,000 to construct, and a request for funding was submitted to Parliament in 1966. This was turned down and the strategic function of the Uckfield line as a link to the south coast was effectively lost. BRB saw little further use for the line and applied for its abandonment.[1]

BRB 1966 Network for Development Plans

It was in 1966 that the Network for Development Plans were issued by Barbara Castle, the Labour Minister of Transport, following a study. Lines that were remunerative, such as the main trunk routes and some secondary lines, would be developed. Those that failed to meet the financial criterion but served a social need were to be retained and subsidised under the Transport Act 1968. The problem would be for lines that were not in the above categories, which could be candidates for closure as they did not form part of the basic railway network. The Hurst Green to Lewes line was one of those that fell into this category. It was a line that carried considerable traffic, and perhaps made a small profit, but it did not meet the government's social, economic and commercial criteria for retention.

Closure announcement

In February 1966, BRB gave notice to Castle under Section 54 of the Transport Act 1962 of its intention to close the line from Hurst Green junction to Lewes.[18] Detailed memoranda were presented relating to the availability of alternative public transport, and statistics as to the usage of the line.[18] The section proposed for closure had figured in the first Beeching Report as an 'unremunerative line', one earning less than £5,000 per annum in revenue.

Pursuant to Section 56 of the Act, the Minister agreed to publication of the Notice for Closure, which was published in September 1966, followed in December by a notice inviting objections.[18] East Sussex County Council responded in February 1967 with a memorandum pointing out that closure would affect an area in which the population was likely to almost double by 1981.[18]

Public enquiry

The number of objections received was almost 3,000 and triggered the requirement under the Transport Act 1962 to hold a public enquiry, at which the merits of the proposal would be examined by the South Eastern Transport Users' Consultative Committee (TUCC). This was held in April 1967.[19]

At the enquiry objectors against closure successfully employed, for the first time, the Ministry of Transport's own cost-benefit analysis, by which the viability of new motorways was measured by calculating the "income" of the road (i.e. its benefit to users and the rest of the network in terms of saved time, fuel etc.) less the costs of its construction and maintenance, to show that the closure of the line would result in 712,000 wasted travelling hours at a cost of around £570,000 per annum.[20] This figure was in contrast to the loss of £276,000 that British Railways was claiming the railway line was losing.[20]

The TUCC presented its report to Castle in June 1967 and recommended against closure of the line, pointing out the "very severe hardship" which would be suffered by those who used it to travel to London.[21] According to the report, this hardship could not be alleviated other than by retaining the lines proposed to be closed as it arose not from lack of alternative bus services, existing or proposed, but from the inherent advantages of the railway to those who use it.[21]

Reconsideration by the Minister

The TUCC report prompted the Minister to revisit her decision and she met the BRB to determine whether alternatives existed to the closure of the entire section.[22] They examined whether the necessary savings could be made by operating on a single track, rationalising the service or keeping the line open with the exception of the Lewes to Uckfield connection.[22] The conclusion was reached that although a complete closure would involve "substantial inconvenience" rather than "outright hardship", this was outweighed by the high cost of retaining the service, including the reconstruction of the Hamsey Loop.[23]

Following Castle's departure from office on 6 April 1968, her successor, Richard Marsh, re-examined the proposed closure in the light of the Government's new policy for the organisation and financing of public transport in the London area set out in the July 1968 White Paper on Transport for London (Cmd. 3686), which proposed that London commuter area services would be jointly managed as a network by the BRB and the Greater London Council.[24] Under the proposals, no subsidy would be paid by the Minister to BRB where a rail closure was refused: the loss would be taken into consideration when fixing financial objectives and levels of service.[24]

In consultation with the BRB, Marsh decided that the section from Hurst Green junction to Uckfield, and Eridge to Tunbridge Wells, was within the London commuter area and could be kept open.[25] However, the line south of Uckfield would close provided that five additional bus services from Lewes and two from Uckfield were provided, together with an extra school bus from Lewes in the afternoon.[26] As Marsh explained in a letter to BRB dated 16 August 1968, the "hardship" caused by the closure of the line north could be alleviated by the provision of buses.[27] He invited the BRB to apply for an unremunerative railway grant for the rest of the line, a new subsidy which would shortly be introduced by Section 39 of the Transport Act 1968.[28]

An unremunerative railway grant was awarded and the Minister formally refused consent to close the section from Hurst Green junction on 1 January 1969, whilst authorising closure of the 10 miles between Uckfield and Lewes and the section between Ashurst Junction and Groombridge Junction.[29] Avoiding the reconstruction of the Hamsey Loop would save on costs and allow the Lewes Relief Road scheme to be speeded up.[25]

Extra bus services

Southdown Motors operated three bus services at the time: no. 19 between Newick and Lewes via Barcombe Cross, and nos. 119 and 122 between Lewes and Uckfield via the A26 with a stop at Barcombe Lane.[30] As a condition of the Minister's consent to closure, additional bus services were laid on from August 1968.[30] No. 122 additionally called at Isfield Station and provided an hourly service to and from Uckfield, but no. 119 departed Uckfield two minutes before the incoming rail service arrived.[30] Barcombe Mills and Isfield stations remained open to sell tickets. However, as the buses were unable to negotiate the narrow winding road to Barcombe Mills, they stopped one mile short of the station: BRB laid on taxis to ferry passengers to the bus stop, but passengers first had to walk to the station to buy their tickets.[31]

The bus company applied for licences to operate the extra services beyond the closure of the line, and their applications were referred to the South East Area Traffic Commissioners whose approval for new bus services was required under the Road Traffic Act 1930.[32]

In the meantime, BRB announced that the last day of service between Uckfield and Lewes would be 6 January 1969 and issued a revised timetable showing the service to Lewes as withdrawn subject to the approval for the bus services. On 11 November 1968, it informed the Ministry that the new timetable would be introduced regardless of the Commissioners' decision.

A public enquiry was held on 27–28 November 1968 and 21 January 1969 at Lewes Town Hall and was chaired by Major General A.J.F. Emslie.[33] The Commissioners were presented with evidence that those currently using the line would, instead of using the new bus services, switch to cars and motorcycles, thereby adding to the congestion problems at Uckfield.[33] It was also suggested that British Rail had drawn up a timetable which was deliberately aimed at showing a loss on the line.[34] Major J.H. Pickering, a member of East Sussex County Council's Roads and Bridges Committee attending the meeting in his personal capacity made the point that "the Minister had ignored the undisputed and rapid growth of population in the area affected by the proposed bus service", the population having increased by 5,000 in three years and was expected to reach 10,000 in the following five years.[33] Crowborough was also expanding at a similar rate.[33]

The grant of new licences was rejected by the Commissioners on the basis of: (i) the lack of services to Barcombe Mills station – passengers were obliged to walk one mile to the bus stop, (ii) the poor off-peak train/bus connections at Uckfield and (iii) traffic congestion at peak times in Tonbridge and Lewes which had a serious effect on bus timings at Uckfield.[32] Following the variation by the Minister of the conditions of closure to provide for extra services, the Commissioners' concerns were met,[32] and authorisation for the bus services was given on 31 March 1969. The last day of operation of the Uckfield – Lewes section would be 6 May 1969.[35]

Lewes Viaduct

Another element in the closure decision was the condition of Lewes Viaduct.[36] The Ministry of Transport had been advised in 1964 by its Divisional Road Engineer that the condition of the viaduct would entail high maintenance costs in the near future.[36] In June 1965, the Engineer reported again that the bridges and viaduct on the line between Barcombe Mills and Lewes were in need of expensive repairs.[36] A speed limit of 10 mph was introduced on the viaduct in September 1967.[36] In March 1968, BRB informed the Ministry that unless the section of line between Lewes and the start of the Hamsey Loop could be eliminated by the end of the year, either by rebuilding the Hamsey Loop or by closing the line, emergency remedial work would be required.[35][36]

On 13 December 1968, BRB's engineers conducted a special investigation of the viaduct.[37] On 16 December, BRB announced that, for safety reasons and as a short-term measure, only the down line could be used by a shuttle service and a revised timetable was introduced to reflect this.[37] On 23 February 1969, this service ceased and was replaced by an emergency bus service.[35][37] BRB's timetabling announcements were criticised by the Traffic Commissioners as giving the impression that a decision on the line's future had been taken before their enquiry was over.[38]

Lewes Relief Road

Within weeks of the line closing, an embankment carrying the line was cut through in preparation of the first stage of the Lewes Relief Road.[39] The remaining bridges from Lewes station to Cliffe High Street and the viaduct over the River Ouse were also demolished. Construction of the Phoenix Causeway was completed in summer 1969, but stages two and three of the Lewes Relief Road project were scrapped; the Council chose instead to link up with the town's new bypass by building Cuilfail Tunnel, which opened in November 1980.[40] A 2001 report by the Environment Agency noted the detrimental effect of the Phoenix Causeway on the town by blocking the floodplain, contributing greatly to the floods of October 2000.[41] As the bypass cut across the railway alignment, the Council's County Engineer gave an undertaking on 11 December 1978 to "pay for the cost of a new bridge and other works over the Uckfield By-pass should the Lewes-Uckfield Railway Line ever be re-opened."[39]

Hamsey Loop

John Peyton, the Conservative Minister for Transport Industries, confirmed on 5 February 1973 that the powers granted by the British Railways Act 1966 in respect of the Hamsey Loop had expired on 31 December 1972.[42] East Sussex County Council agreed nevertheless to safeguard the trackbed against development.[15] However, the Council declined British Rail's offer to acquire the alignment for £1 in the 1970s and much of the trackbed was consequently disposed of by British Rail in the 1980s for a few thousand pounds.[39]

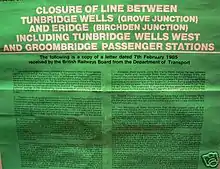

Eridge to Tunbridge Wells

Following a lack of investment for decades, by the early 1980s the track and signalling between Eridge and Tunbridge Wells needed to be replaced. British Rail, at the time carrying out an upgrade of the Tonbridge to Hastings Line, decided that the costs of keeping the line from Eridge open and undertaking the resignalling and relaying Grove Junction works did not justify the outlay. As part of a financial package to secure funding for the £24m electrification of the Hastings Line, British Rail agreed to close the line, with the valuable site of Tunbridge Wells West being sold to Sainsbury's for £4m.[43] The line also suffered from poor patronage due to lack of timetable co-ordination and a limited service since 1971 of an hourly off-peak shuttle service between Tonbridge and Eridge with extra services during Monday to Friday peak hours.[43]

Closure of the line (including Groombridge and Tunbridge Wells West stations) was therefore announced from 16 May 1983, subsequently postponed following objections. The Secretary of State for Transport approved the decision with effect for passenger trains from 6 July 1985, although empty stock trains continued to use the section from Tunbridge Wells West to Birchden Junction until 10 August when the depot at West station closed.[44] Despite closure of the line and redevelopment of the Tunbridge Wells West site, a corridor was left so that a reinstated railway could run through the site alongside Linden Park Road and in front of the old station building, allowing it to reconnect with the extant track through to Groombridge.[43] An undertaking was obtained from Sainsbury's in 1995 by local MP Patrick Mayhew following the construction of a toilet block which impeded the route of the line; Sainsbury's agreed that it would demolish the toilet block if this became necessary.[43]

Uckfield station

.jpg.webp)

In 1991, Uckfield station was resited on the eastern side of the level crossing over the High Street to avoid the need to close the barriers when trains entered the station and unnecessary traffic build-up.[45] The former station building fell into disrepair and, after suffering vandalism and arson, was demolished in December 2000.[46]

At the same time, the track across the road was removed by East Sussex County Council despite concerns that this action would create an obstacle to reopening the line in terms of the loss of any grandfather rights.[39] A new modular station building was provided for the re-sited Uckfield station, replacing the temporary portakabin-type structure initially provided.[46] On 14 May 2013, it was announced that Network Rail had agreed terms to purchase the 4.7 acre site of the old station from BRB (Residuary) Limited.[47] In Summer 2015, a 174-space car park was opened on the old station site on land clear of the former route alignment.[48]

Revival

Lavender Line

In 1983, Isfield station and a length of trackbed were purchased by an enthusiast who restored the station, built a locomotive shed and laid a short length of track.[49] The owner ran out of money and the property passed in 1991 to the Lavender Line preservation society, which took over and further restored the station.[49] The society has also restored about one mile of track to the north of Isfield.[49]

Spa Valley Railway

The Tunbridge Wells and Eridge Railway Preservation Society was formed shortly after the closure of the section of the line between Tunbridge Wells and Eridge with the intention to re-open the connection. It purchased the line and trains were again running by 1996 on The Spa Valley Railway. The line extends for four miles from Tunbridge Wells West to Birchden Junction, and another mile to Eridge (alongside the National Rail line) opened on 25 March 2011.

Wealden Line Campaign

Launched in 1986, the Wealden Line Campaign is seeking the full restoration of services between Lewes and Tunbridge Wells, with eventual electrification. The scheme has received the support of the MPs for Lewes and Wealden, Norman Baker and Charles Hendry, who have both made repeated calls in the House of Commons for the re-opening of the line.

Uckfield Line Rail Extensions group

In June 2009, following a meeting of the Uckfield Railway Line Parishes Committee, an informal association of members from local parishes who meet monthly to press for the line's reinstatement, it was decided to set up a new organisation comprising elected representatives from town and parish councils in Crowborough, Lewes and Buxted.[50] Named the Uckfield Line Rail Extensions Group (Ulreg), it seeks to apply political pressure for the reinstatement of the line.[51]

Calls for reopening and feasibility studies

Post-closure

The merits of the Uckfield-Lewes closure were debated on several occasions in Parliament following closure. In particular, it was argued that the line would have provided a valuable alternative route to the Brighton Main Line when that line was out of action, as was the case on 16 December 1972 when a collision between two passenger trains at Copyhold Junction closed the line for over a month. Lord Teviot referred to this incident when calling for the reinstatement of the line in the House of Lords on 20 May 1974. It was estimated that costs of reinstatement would be in the region of £2 million, together with an additional revenue subsidy of £170,000 per year.[52]

1980s and 1990s

In February 1987, Network SouthEast agreed to contribute £1.5 million to reinstate the Lewes to Uckfield Line, a quarter of its projected cost. The scheme floundered in the face of a lack of funding from other sources, both the Kent County Council and East Sussex County Council proving to be "uncooperative" on this score.[53]

In 1996, a feasibility study was commissioned by the Kent County Council into the re-opening of the Tunbridge Wells to Eridge section of the line. The report, prepared by Mott MacDonald, found in favour of reopening the line, concluding that "at a reinstatement cost of £20–25 million such a long-term reinstatement facility (which might substitute for more expensive road infrastructure elsewhere) might be considered a relatively cheap option".[54] The project made no progress.

Connex

Hopes for reopening were raised in 2000 when Connex South Central included the reinstatement of the line in its ultimately unsuccessful bid for the South Central franchise, and later by Railtrack, which not only looked at reopening, but also the electrification of the whole route.[1] In 2002, the Department of Transport on the advice of the Strategic Rail Authority stated that the costs of electrification from Uckfield to Hurst Green "far outweigh the benefits", but the situation would be kept under review.[55]

Central Rail Corridor Board

To take the case for reinstatement forward, a "Central Rail Corridor Board" was set up in 2004, with members from regional, county and district levels, local MPs and Southern. The Board, led by East Sussex County Council, oversaw the development of initiatives to explore the feasibility of reinstatement and provide guidance on the political, planning and transport policy framework. A free scoping study was prepared by a consortium of transport and engineering consultants, who recommended in March 2005 that there were sufficient grounds for proceeding to a full feasibility study at a cost of £150,000, the funding for which was provided by numerous local authorities in the area.[56]

On 14 June 2007, members of the Campaign met the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Transport, Tom Harris, who agreed to consider the results of the feasibility study.[57] As Harris later revealed to Parliament, the Campaign members proposed a public-private partnership, which "would mean, in essence, that the Department for Transport would not have to put its hand in its pocket for the capital costs or for revenue costs following resumption of services on the line."[58] The financial viability of the proposals would be tested by the feasibility study, and the Minister indicated that some investment would have to be forthcoming from the Campaign.

Network Rail pledged to consider the results of the study and investigate all possible commercial avenues for the line's reopening. The study, which was overseen by Network Rail and due to commence in September 2007, was delayed until January 2008; its costs, which were estimated to be in the region of £130,000 to £140,000, were met by the Central Rail Corridor Board.[59] In March 2008 the Wealden Line Campaign launched "Wealdenlink – Capacity Solutions for Sussex, Kent, Surrey and London", a presentation outlining the benefits of reinstatement which aims to give new impetus to the project at a critical moment.[60]

Final report

The reinstatement feasibility study was released on 23 July 2008 accompanied by a press release by East Sussex County Council[2] It said that whilst reinstatement was technically feasible, it would not be economically viable.[61][62]

The full report first assessed the cost implications of three possible construction options: a 'base option' which would see the line rebuilt according to minimum specification, an 'intermediate stations option' which examined rebuilding with the provision of stations at Barcombe Mills and Isfield and a 'double track option' where the line would be dualled throughout.[63] The preferred route in terms of cost effectiveness and ease of construction was identified as the rebuilding of the Hamsey Loop on an alignment slightly to the north of the original 1858 route and joining the Brighton Main Line a point south of the level crossing in the village of Hamsey.[64] The reconstruction of the original line along the east bank of the River Ouse and through Lewes town centre was not examined due to cost implications.[65] The total cost of the base option was estimated at £141m, which included a 30% contingency as per GRIP stage 2 procedure.[66] With the two additional stations, costs would rise under the second option by £7.4m,[67] while the final option resulted in an estimated figure of £38.8m.[68]

Assessing the potential traffic to be generated by the new line, the report estimated that between 1,500 and 2,000 trips per day (450,000 to 620,000 trips per annum) would be generated by a variety of routes including London-Uckfield-Eastbourne and London-Uckfield-Newhaven fast services.[69] The majority of trips would, however, be to existing stations on the Uckfield-Croydon line and the south-coast,[70] while the new routes would encourage only 2% growth for existing lines due to longer journey time to the south coast compared with the Brighton Main Line.[71] The benefit of the reinstated line as a diversionary route was judged negligible due to the low occurrence of total closures on the Brighton line, so was not taken into consideration in the business case.[72]

For the business case, six route options were tested: 2A (London-Uckfield-Eastbourne fast), 2B (London-Uckfield-Eastbourne, with stations at Isfield and Barcombe), 3A (London-Uckfield-Newhaven fast), 3B (London-Uckfield-Newhaven, with the two new stations), 4A (London-Uckfield-Lewes fast) and 4B (London-Uckfield-Lewes new stations).[73] The study concluded that all six routes showed a negative net present value and therefore had a poor business case as the value of the new line to users and non-users were less than the costs of construction; options 2A and 2B would in addition generate losses for the train operator.[74] The best performing option was 4B which generated a benefit–cost ratio of 0.79,[74] with an annual revenue forecast of £4.46m against potential operating costs of £3.11m.[71] Option 4B came in with a slightly lower BCR of 0.78,[75] with annual revenues of £3.71m at a cost of £2.28m.[76] The report concluded that the BCRs produced for each option represented 'poor value for money' as per DfT guidance.[77]

The report explained that the poor business case was due to the low level of demand for the reopened route and increased car ownership since the 1960s.[78] In order to improve the business case, there would need to be a significant increase in the size of the population along the line and/or a fundamental shift in the travelling population of the existing population.[79][80]

Criticism

The final report was criticised by Uckfield Town Council and Lewes MP, Norman Baker, for its narrow scope.[81] According to Railfuture, a positive business case was not established as the potential stakeholders were not all aligned, actively supporting and promoting the proposal, and because the terms of reference were defined too narrowly, so that the study could not look at all the possible solutions to determine which would be most viable and could be funded soonest.[82]

Kilbride group

In autumn 2004, the Kilbride Group, a private company specialising in combining residential development with transport-infrastructure improvements, expressed interest in restoring services. The company, already involved in a similar project to reconnect Bere Alston and Okehampton on the West of England Main Line, believed that the cost of reinstatement could be met by imposing a levy on each house built based on the housing targets for the area (around 4,000 houses). The costs of reinstatement were estimated at £50m, significantly different from the results from the Network Rail analysis. Kilbride's offer was declined by East Sussex County Council.[83]

In November 2008, following the failure to establish a sound business case for reinstatement, Kilbride met members of Uckfield Town Council to confirm that the link could be financed by revenue from the housing projects already planned for the area.[84]

ATOC report

Crowborough, Lewes and Uckfield councils decided to undertake their own feasibility study and engaged the Jacobs transport consultancy to undertake the work.[85] The Uckfield-Lewes line was identified as a "potential link line" in the 2009 report by the Association of Train Operating Companies entitled Connecting Communities: Expanding Access to the Rail Network.[86] This was reiterated in Network Rail's draft Route Utilisation Strategy for Sussex, published on 26 May 2009, which stated that the line's reinstatement would "provide potential capacity relief to the southern end of the BML."[87]

Brighton Main Line capacity study

On 9 May 2013, the Secretary of State for Transport, Patrick McLoughlin, announced that the Department for Transport had asked Network Rail to explore the possible re-opening of the Lewes to Uckfield route.[88] The study, which was published in May 2014, outlined the capacity strategy for the Brighton Main Line for the period 2014-2024.[89] The study's key recommendation was that capacity interventions should be concentrated on alleviating bottlenecks on the existing line, instead of investment in alternative routes such as Lewes-Uckfield.[89] Such alternative routes were, according to the study, of limited value in the short to medium term.[89] The study found in particular that it would be difficult to accommodate additional Lewes-Uckfield services on the Brighton Main Line due to capacity limitations, and indicated that there may be a long-term case for reinstatement, possibly in conjunction with new lines for the London section of the Brighton Main Line.[89] The Department for Transport accepted the recommendation.[90]

London and South Coast Rail Corridor Study

In 2015, the government appointed the consultants WSP/Parsons Brinckerhoff to look at the strategic case for investing in new capacity along the south coast rail corridor.[91] Published in March 2017, the study addressed three key points: Network Rail's planned upgrade package for the Brighton Main Line, the opportunities in reopening Lewes-Uckfield and/or an alternative relief route north ('BML2'), and the potential for high-speed rail connections between London, Gatwick Airport and Brighton.[92] It concluded that pursuing Network Rail's upgrade package was a strategic priority, but rejected the case for BML2 or a Lewes-Uckfield link.[93] The study did acknowledge that the viability of both schemes could be improved by local communities accepting significant additional housing and commercial development.[94] In any case, a new line running north from Croydon, either towards Lewisham and the Docklands area or a fast connection to central London, was considered as unnecessary until at least the 2040s/2050s.[94] The study's recommendations were accepted by the government.[95]

Restoring your railway

In February 2020, a bid was made to the Restoring Your Railway fund for a feasibility study into reinstating the line between Lewes and Uckfield as well as Tunbridge Wells and Eridge.[96] The bid, which was submitted by Lewes MP Maria Caulfield and the BML2 project team, and supported by Brighton MPs Caroline Lucas and Lloyd Russell-Moyle, was for £50,000 to develop a business case.[97][98] The bid was turned down by Transport Minister Chris Heaton-Harris in November 2021 on the basis that train travel was not expected to return to pre-pandemic levels.[98][99]

Transport for the South East

In March 2023, Transport for the South East proposed the reinstatement of the lines from Uckfield-Lewes and Tunbridge Wells Central-Tunbridge Wells West as a means of enhancing east-west connectivity and improving the resilience of radial corridors.[100]

References

Notes

- Broadbent (2008), p. 48.

- "Issued on behalf of the Central Rail Corridor Board: Rail study report concludes that reinstatement is not economically viable" (Press release). East Sussex County Council. 23 July 2008. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Stones (1969), p. 497.

- Course (1974), pp. 73–74.

- White (1992), p. 92.

- White (1987), pp. 50–51.

- Stones (1969), p. 498.

- Course (1974), pp. 79–80.

- Course (1974), p. 80.

- Stones (1969), p. 500.

- Stones (1969), p. 499.

- Oppitz (2001), p. 30.

- Mitchell & Smith (1986), p. 2.

- "Tragic miscalculation broadside at bus services enquiry". Sussex Express. 24 January 1969. Archived from the original on 11 March 2005. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- Brian Abbott, Wealden Line Campaign (March 2008). "Wealdenlink presentation" (PDF). Retrieved 11 May 2008.

- Compton (1970), para. 26.

- Brian Abbott, HMSO (1966). "British Railways Act 1966" (PDF). Railways Archive. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- Compton (1970), para. 10.

- Compton (1970), para. 11.

- Henshaw (1994), pp. 184–185.

- Compton (1970), para. 12.

- Compton (1970), para. 13.

- Compton (1970), para. 14.

- Compton (1970), para. 15.

- Compton (1970), para. 16.

- "Kent-Sussex Line may qualify for a grant". The Times. UK. 23 August 1968. pp. 2, Col. A.

- Compton (1970), para. 17.

- "Minister's 'no' to rail closure". Evening Argus. 7 January 1969. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- Compton (1970), para. 18.

- Compton (1970), para. 19.

- Oppitz (2001), p. 31.

- Compton (1970), para. 20.

- "British Rail slammed over line closing plans". Kent and Sussex Courier. 27 January 1969. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- "British Rail have to think again about closure date". Sussex Express. 6 December 1968. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- White (1987), p. 65.

- Compton (1970), para. 23.

- Compton (1970), para. 24.

- Compton (1970), para. 25.

- "Lewes – Uckfield: A Case Unanswered" (PDF). Wealden Line Campaign. 22 June 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- Hitchin, David (4 September 2009). "Wrong tunnel". The Argus. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- Environment Agency (March 2001). Flood Report (Report). Lewes District Council. Archived from the original (DOC) on 19 May 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "Hansard Debates vol 850 c36W". House of Commons. 5 February 1973. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- "Justification for TWBC retaining transport policy and protection for the railway from Tunbridge Wells to Eridge" (PDF). Royal Tunbridge Wells Town Forum. February 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- Catford, Nick. "Tunbridge Wells West". Subterranea Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 October 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- "The lost and abandoned East and West Sussex railway stations". Sussex Live. 21 January 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- "New station opens at Uckfield for passengers". Network Rail. 16 March 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- "New station car park for Uckfield 'within 12 months'". East Sussex County Council. 13 May 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- Blake, Roger (24 July 2016). "Southern comfort". Railfuture. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- Oppitz (2001), pp. 33–35.

- "Uckfield and Lewes railway line has a new campaign group". Kent and Sussex Courier. 18 June 2009. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "Minutes of the meeting of the Council held at High Hurstwood Village Hall on Tuesday 9 June 2009 at 7.30 pm". Buxted Parish Council. 9 June 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- "Hansard Debates vol 351 cc1301-12". House of Lords. 20 May 1974. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- Henshaw (1994), p. 251.

- "Hansard Debates". House of Commons. 29 July 1998. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- "Written Answers". House of Commons. 9 July 2002. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- Report on Reinstatement of the Lewes-Uckfield Line (Report). Lewes District Council. 30 March 2006. Archived from the original (DOC) on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "Fresh hope of railway reopening". BBC News. 14 June 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- "Hansard Debates, Column 134WH". House of Commons. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- "Railway route study gets go-ahead". BBC News. 3 January 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- "Case made for reopening rail link". Sussex Express. 18 March 2008. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "Railway line defeat 'just a blip'". BBC News Online. 23 July 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 4.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 7.

- Network Rail (2008), pp. 10–11.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 11.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 22.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 25.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 28.

- Network Rail (2008), pp. 38–39.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 41.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 38.

- Network Rail (2008), pp. 44–45.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 52.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 54.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 61.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 50.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 62.

- Network Rail (2008), p. 83.

- Network Rail (2008), pp. 83–84.

- "Lewes-Uckfield rail link". East Sussex County Council. 4 August 2008. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- "Authorities Clash Over Uckfield To Lewes Report". Railnews. 30 July 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- "Uckfield business case". Railfuture. 28 December 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- Broadbent (2008), pp. 48–49.

- "New hope for disused line". The Argus. 20 November 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- "Rail alliance". Railfuture. 9 April 2009. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "Connecting Communities – Expanding Access to the Rail Network" (PDF). London: Association of Train Operating Companies. June 2009. p. 21. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- "Sussex Route Utilisation Strategy Draft for Consultation" (PDF). Network Rail. 26 May 2009. p. 154. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- "Lewes-Uckfield rail route to be re-examined". Department for Transport. 9 May 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "Brighton Main Line: emerging capacity strategy for control period 6 pre-route study report" (PDF). Network Rail. 1 May 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- "Brighton Main Line: DfT's response to Network Rail's report". Department for Transport. 1 May 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- "Brighton mainline 2 campaigners optimistic as feasibility report delayed until autumn". Brighton and Hove News. 24 March 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- "We need a long term plan for the Brighton Main Line". Greengauge 21. 5 April 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- "DfT brands Brighton Main Line a 'strategic priority' but ditches BML2 scheme". Rail Technology Magazine. 2 March 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- "London and South Coast Rail Corridor Study" (PDF). Department for Transport. April 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- "London and south coast rail corridor study: government response". Department for Transport. 2 March 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- "Lewes to Uckfield Line a step closer following launch of Restoring Your Railway fund". Maria Caulfield. 6 February 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- "The last chance to reinstate the Lewes to Uckfield rail link came a step closer last week". Maria Caulfield. 10 March 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- Wadsworth, Jo (16 November 2021). "New Brighton mainline campaign loses out on government cash". Brighton and Hove News. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- King, Susan (18 January 2022). "Uckfield to Lewes rail campaigner says MP Maria Caulfield has been 'hung out to dry' by Government over link". Sussex World. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- "London to Sussex Coast Strategic Programme Outline Case" (PDF). Transport for the South East. 23 March 2023. p. 58. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

Sources

- Broadbent, Steve (2008). "The Battle of Wealden". Rail (599 (27 August – 9 September)): 46–51.

- Compton, Edmund (9 April 1970). The Compton report (Report). Parliamentary Commissioner for Administration. Archived from the original on 12 April 2005. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- Course, Edwin (1974). The Railways of Southern England: Secondary and Branch Lines. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd. ISBN 0-7134-2835-X.

- Henshaw, David (1994). The Great Railway Conspiracy. Hawes, North Yorkshire: Leading Edge. ISBN 0-948135-48-4.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1986). Branch Lines to Tunbridge Wells from Oxted, Lewes and Polegate. Midhurst, West Sussex: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-0-906520-32-1.

- Network Rail (July 2008). Lewes-Uckfield Railway Line Reinstatement Study 2008 (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- Oppitz, Leslie (2001). Lost Railways of Sussex (Lost Railways). Newbury, Berkshire: Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-85306-697-9.

- Stones, H.R. (1969). "Farewell to the Lewes & Uckfield". Railway Magazine. 115 (821 (Sept.)): 496–500.

- White, H.P. (1992). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Southern England (Volume 2). Nairn, Scotland: David St John Thomas. ISBN 978-0-946537-77-8.

- White, H.P. (1987). Forgotten Railways: South-East England (Forgotten Railways Series). Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-946537-37-2.

External links

Source materials

- "BRB Network for Development Plans 1967" (PDF). (501 KiB)

Stations on the line

- Barcombe Mills railway station on Subterranea Britannica

- Isfield railway station on Subterranea Britannica

- Uckfield railway station on Subterranea Britannica

- Eridge railway station on Subterranea Britannica

- Groombridge railway station on Subterranea Britannica

- High Rocks railway station on Subterranea Britannica

- Tunbridge Wells West railway station on Subterranea Britannica