Well-made play

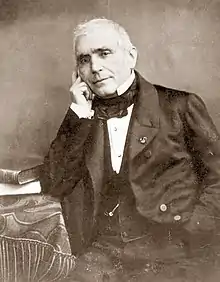

The well-made play (French: la pièce bien faite, pronounced [pjɛs bjɛ̃ fɛt]) is a dramatic genre from nineteenth-century theatre, developed by the French dramatist Eugène Scribe. It is characterised by concise plotting, compelling narrative and a largely standardised structure, with little emphasis on characterisation and intellectual ideas.

Scribe, a prolific playwright, wrote several hundred plays between 1815 and 1861, usually in collaboration with co-authors. His plays, breaking free from the old neoclassical style of drama seen at the Comédie Française, appealed to the theatre-going middle classes. The "well-made" form was adopted by other French and foreign playwrights and remained a key feature of the theatre well into the 20th century.

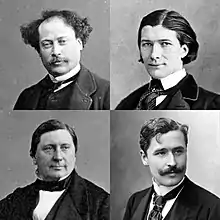

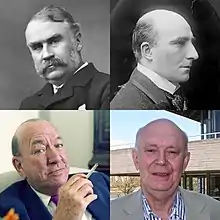

Among later playwrights drawing on Scribe's formula were Alexandre Dumas fils, Victorien Sardou and Georges Feydeau in France, W. S. Gilbert, Oscar Wilde, Noël Coward, and Alan Ayckbourn in Britain, and Lillian Hellman and Arthur Miller in the US. Writers who objected to the constraints of the well-made play but adapted the formula to suit their needs included Henrik Ibsen and Bernard Shaw.

Definitions

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the "well-made play" as one "written in a formulaic manner which aims at neatness of plot and foregrounding of dramatic incident rather than naturalism, depth of characterization, intellectual substance, etc."[2] The Oxford Encyclopedia of Theatre and Performance (2004) elaborates on the definition: "A dramatic structure [designed] to provide a constantly entertaining, exciting narrative which satisfyingly resolved the many complications and intrigues that drove the story … characteristically based on a secret known only to some of the characters".[3]

The formula came into regular use in the early 19th century and shaped the direction of drama over several decades, but its various elements contained nothing unknown to previous generations of writers, and neither its first proponent, Eugène Scribe, nor his successors applied it unvaryingly. The academic Stephen Stanton (1957) gives seven key points of the genre, which may be summarised as:[4]

- a plot based on facts known by the audience but not known by some or all of the characters

- a pattern of increasingly intense action and suspense

- a series of ups and downs in the main character's fortunes

- the depiction of the lowest and the highest point in the main character's adventures

- a central misunderstanding or quiproquo (see below), clear to the audience but unknown to the characters

- a logical and plausible dénouement

- the overall structure is reflected in each act.

Within the structure of the well-made play three technical terms are frequently used:

- quiproquo – (derived from post-classical Latin quid pro quo: literally, "something for something"): two or more characters interpret a word, a situation or a person's identity in different ways, all the time assuming that their interpretations are the same.[5]

- peripeteia – used in this context as meaning the greatest in a series of mishaps suffered by the hero.[n 1]

- scène à faire (the "obligatory" scene) – a term invented by the 19th-century critic Francisque Sarcey – a scene in which the outcome the audience expects and ardently desires comes to pass or is clearly signalled.[8]

Background

Before the late-18th century, French theatre had been neoclassical in style, with strict forms reflecting contemporary interpretations of the theatrical laws propounded by Aristotle in his Poetics, written some 1,500 years earlier. The prevailing doctrine was "verisimilitude", or the appearance of a plausible truth, as the aesthetic goal of a play.[9]

In 1638 the Académie Française codified a system by which dramatists should achieve verisimilitude, and the monarchy enforced the standards of French neoclassicism by licensing and subsidising a limited number of approved theatre companies, chief of which was the Comédie Française.[10] Corneille and Racine were regarded as successors to the ancient Greek tragedians, and Molière as that of Plautus and Terence in comedy.[11]

Small companies performing simple plays at local fairs were tolerated, and by the middle of the 18th century some were playing in Paris in the Boulevard du Temple, bringing before the public works not constrained by neoclassical formulas.[12]

Scribe

The dramatist and opera librettist Eugène Scribe was born in 1791, at a time when the conventions and forms of the traditional European literature and theatre of the neoclassical Enlightenment were giving way to the unrestrained and less structured works of Romanticism.[13] In his 1967 book The Rise and Fall of the Well-Made Play, John Russell Taylor writes that what Scribe set out to do "was not to tame and discipline Romantic extravagance, but to devise a mould into which any sort of material, however extravagant and seemingly uncontrollable, could be poured".[13] Writing with collaborators as a rule, Scribe produced some 500 stage works between 1815 and his death in 1861.[14] His development of a form that could be used repeatedly to turn out new material met the demands of a growing middle class theatre audience,[15] and made him a rich man.[16]

Many of Scribe's plays were produced at the Théâtre du Gymnase, where he was resident dramatist from 1851. He specialised at first in vaudeville, or light comedy, but soon developed the pièce bien faite, frequently (though not invariably) using the form, both for comic and serious plays, keeping the plots tight and logical, subordinating character to situation, building up suspense, and leading up to the resolution in a scène à faire.[17] A later critic commented:

A Scribe play, long or short, is a masterpiece of plot construction. It is as artistically put together as a master watch; the smallest piece is perfectly in place, and the removal of any part would ruin the whole. Such a "well-made" play always displays fertility of invention, dexterity in the selection and arrangement of incidents, and careful planning. Everything is done with the greatest economy. Every character is essential to the action, every speech develops it. There is no time for verbal wit, no matter how clever, or for philosophical musing, no matter how enlightening. The action is all-important.[18]

Scribe's formula proved immensely successful, and was much imitated, despite objections at the time and later that the constraints of the well-made play turned characters into puppets controlled by chance,[17] and that the plays displayed "shallow theatricality".[19] He is remembered more for his influence on the development of drama than for his plays, which are rarely staged; Les Archives du spectacle record numerous French productions in the 20th and 21st centuries of works by Scribe, but these are almost all operas with his librettos rather than his non-musical plays.[20]

Influence

France

Scribe's influence on theatre, according to the theatre historian Marvin Carlson, "cannot be overestimated", and French playwrights of the 19th century, even those who reacted against Scribe and his well-made plays, were all influenced by them to a greater or lesser degree.[21] Carlson observes that, unlike other influential theatre thinkers, Scribe did not write prefaces or manifestos declaiming his ideas. He influenced theatre, instead, with craftsmanship. Carlson identifies a single instance of Scribe's critical commentary from a speech the playwright gave to the Académie Français in 1836. Scribe expressed his view of what draws the audiences to the theatre:

not for instruction or improvement, but for diversion and distraction, and that which diverts [the audience] most is not truth, but fiction. To see again what you have before your eyes daily will not please you, but that which is not available to you in everyday life – the extraordinary and the romantic."[21]

Although Scribe advocated a theatre of entertainment rather than of deep ideas, other writers, beginning with Alexandre Dumas, fils, adopted Scribe's structure to create didactic plays. In a letter to a critic, Dumas fils wrote, "... if I can find some means to force people to discuss the problem, and the lawmaker to revise the law, I shall have done more than my duty as a writer, I shall have done my duty as a man".[22] Dumas' thesis plays, written in the "well-made" genre, take clear moral positions on social issues of the day. Emile Augier also used Scribe's formula to write plays addressing contemporary social issues, although he declares his moral position less forcefully.[23]

Victorien Sardou followed Scribe's precepts, producing numerous examples of the well-made play from 1860 into the 20th century, not only at the Comédie-Française and commercial theatres in Paris, but also in London and the US. His subject matter included farce and light comedy, comedy of manners, political comedy and costume dramas both comic and serious. The critic W. D. Howarth writes that Sardou's "well-developed sense of theatre and meticulous craftsmanship" made him the most successful dramatist of his day.[24]

Although so far as serious drama was concerned there was a reaction against Scribe's formulaic precepts in the later years of the 19th century, nevertheless in comedy, and in particular in farce, the pièce bien faite remained largely unchallenged. First Eugène Labiche and then Alfred Hennequin, Maurice Hennequin and Georges Feydeau wrote successful and enduring farces that closely follow Scribe's formula, while refreshing the content of the plots.[25]

Britain and US

In the mid-19th century Tom Taylor established himself as a leading London playwright. He adapted many French plays, including at least one of Scribe's,[n 2] and made extensive use of Scribe's formula for the well-made play in his own pieces.[27] Other Victorian playwrights who followed Scribe's precepts to a greater or lesser extent were Edward Bulwer-Lytton, T. W. Robertson, Dion Boucicault and W. S. Gilbert, the last of whom, like Scribe, was an extremely successful opera librettist as well as author of many non-musical plays. Stanton sees the influence of Scribe in Gilbert's best-known play, Engaged (1877), as regards both the plot and the dramatic technique – withheld secrets, exposition, peripeteia and obligatory scene.[1]

Among the next generation of English-language playwrights indebted to Scribe was Bernard Shaw; despite Shaw's frequent denigration of Scribe (see "Objections", below), the latter's influence is seen in many of Shaw's plays. Stanton writes, "The evidence suggests that Shaw availed himself of as many of the tricks and devices of the popular stagecraft of Scribe as would help him to successfully establish on the stage his early plays, from Widowers' Houses (1892) to Man and Superman (1903), and even beyond".[27] Shaw's contemporary Oscar Wilde followed the pattern of the well-made play in his drawing room dramas, but unlike Scribe he introduced continual bons mots into his dialogue, and in his final masterpiece The Importance of Being Earnest (derived in part from Engaged)[28] he abandoned any pretence of plausibility of plot and made fun of many of the traditions of the well-made play.[29]

In John Russell Taylor's view, Arthur Wing Pinero brought the well-made play to its pinnacle so far as the English theatre was concerned, not only in his farces and comedies, but also in serious plays. Pinero did not regard the well-made play as sacrosanct, and wrote many plays in which he avoided the conventional formulas, including his best-known, The Second Mrs Tanqueray (1893).[30] After Pinero, in 20th-century British plays, the well-made play came to be seen as appropriate for comedies, but not for serious works. The comedies of Somerset Maugham were generally of the well-made genre, although he deliberately stretched plausibility to its limits; Noël Coward worked within the genre although his plotting was rarely complex and often slight; Taylor considers that he revived and refined the genre.[31] With Terence Rattigan the English tradition of the well-made play was thought to have come to an end.[32][n 3] Some writers have noted a resurgence: Taylor finds elements of it in Harold Pinter, with the important exception that Pinter's plays deliberately eschew crisp exposition of the plot,[34] and in a 2008 study, Graham Saunders identifies Alan Ayckbourn, Michael Frayn and Simon Gray as playwrights continuing to write well-made plays.[35]

Stanton writes that in the US the situation in the 20th century was much the same as in Britain so far as the well-made play was concerned:

The volumes of George Odell's Annals of the New York Stage record frequent revivals of plays by Scribe and by dramatists who used his technique. Despite a gradual shift after the First World War from the play with a well-made plot toward the play of mood, the Scribean play has not been demolished.[36]

From the US, Stanton singles out The Little Foxes (1939) and Watch on the Rhine (1941) by Lillian Hellman and All My Sons (1946) by Arthur Miller as prominent examples.[36]

Objections

In the later 19th century and subsequently, the principal objection to Scribe's model, so far as serious plays were concerned, was that their concentration on plot and entertainment was limiting for playwrights who wished to examine character or discuss a social message. His admirer Dumas fils alluded to this by saying that the greatest playwright who ever existed would be one who knew humanity like Balzac and the theatre like Scribe.[n 4]

Henrik Ibsen was often a preferred model for those who turned against the well-made play. He took the Scribean form but changed it in one important respect: replacing the scène à faire with a dissection of the social or emotional aspects of the plot.[27] As his disciple Shaw put it: "up to a certain point in the last act, A Doll's House is a play that might be turned into a very ordinary French drama by the excision of a few lines, and the substitution of a sentimental happy ending for the famous last scene".[38]

Shaw was given to disparaging those he imitated, such as Scribe and Gilbert,[39] and wrote, "Who was Scribe that he should dictate to me or anyone else how a play should be written?"[27] Shaw was particularly dismissive of Sardou, for his concentration on plot rather than character or ideas – "Sardoodledom", as Shaw called it – but he nonetheless used the established techniques to convey his own didactic ideas, as he admitted in his preface to Three Plays for Puritans (1900), almost 40 years after Scribe's death.[27] In a study for the Modern Language Association, Milton Crane includes Pygmalion, Man and Superman, and The Doctor's Dilemma among those of Shaw's plays in the "well-made" category.[40]

Notes

- In classical drama the term means a sudden change by which the hero's fortunes veer round to their opposite – good or bad,[6] but in 19th-century French drama it had been narrowed down to mean the nadir of the central character's fortunes.[7]

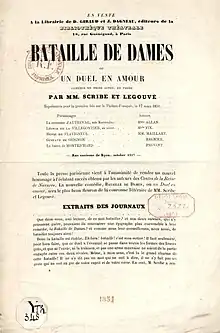

- L'Ours et le Pasha, a farce, adapted by Taylor, with George C. Bentinck and Frederick Ponsonby as The Barefaced Impostors was staged in 1854.[26] Taylor translated another Scribe play, La Bataille de dames, given as The Ladies' Battle in 1851.[27]

- The critic John Elsom suggests that J. B. Priestley's 1946 An Inspector Calls may in some ways be considered a "well-made play", although the author adds a twist replacing the expected happy ending with the prospect of a further ordeal for the characters.[33]

- "L'auteur dramatique qui connaîtrait l'homme comme Balzac et le théâtre comme Scribe serait le plus grand auteur dramatique qui aurait jamais existé."[37]

References

Footnotes

- Stanton, Stephen. "Ibsen, Gilbert, and Scribe's 'Bataille de Dames'", Educational Theatre Journal, March 1965, pp. 24–30 (subscription required) Archived 2021-06-05 at the Wayback Machine

- "well-made". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Rebellato, Dan. "well-made play" Archived 2021-01-21 at the Wayback Machine, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Theatre and Performance, Oxford University Press, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 June 2021. (subscription required)

- Stanton, pp. xii–xiii

- "quiproquo" Archived 2020-08-21 at the Wayback Machine, Dictionnaire de l'Académie française. Retrieved 5 June 2021

- "peripeteia". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Stanton, p. xii

- Archer, p. 173

- Brockett, pp. 158–159

- Brockett, pp. 268, 284, 286 and 386

- Brockett, p. 272

- Brockett, pp. 370–372

- Taylor, pp. 11–12

- Taylor, p. 12

- Koon and Switzer, pp. 33 and 123

- Cardwell, Douglas "The Well-Made Play of Eugène Scribe", The French Review, May, 1983, pp. 876–884 (subscription required) Archived 2021-06-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Howarth, W. D. "Scribe, Augustin-Eugène" Archived 2021-06-06 at the Wayback Machine, The Companion to Theatre and Performance, Oxford University Press, 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2021 (subscription required)

- Tolles, pp. 22–23

- Walkley, p. 44

- "Eugène Scribe" Archived 2021-05-07 at the Wayback Machine, Les Archives du spectacle. Retrieved 4 June 2021

- Carlson, p. 216

- Brocket, p. 507

- Carlson, p. 274

- Howarth, W. D. "Sardou, Victorien", The Companion to Theatre and Performance, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 June 2021 (subscription required) Archived 6 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Heyraud, Violaine. "Oser la nouveauté en usant les ficelles" Archived 2021-06-05 at the Wayback Machine, Université Paris Sorbonne. Retrieved 5 June 2021

- Tolles, p. 276

- Stanton, Stephen S. "Shaw's Debt to Scribe", PMLA, December 1961, pp. 575–585 (subscription required) Archived 2021-06-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Rowell, pp. 11 and 13

- Taylor, pp. 89–90

- Taylor, pp. 52, 54 and 60

- Taylor, pp. 99 and 127

- Taylor, p. 160

- Elsom, p. 45

- Taylor, p. 163

- Saunders, Graham. "The Persistence of the 'Well-Made Play' in British Theatre of the 1990s" Archived 2021-06-05 at the Wayback Machine, University of Reading, 2008. Retrieved 5 June 2021

- Stanton, p. x

- Lacour, p. 174

- Shaw, p. 219

- Holroyd, pp. 172–173

- Crane, Milton. "Pygmalion: Bernard Shaw's Dramatic Theory and Practice", PMLA, December 1951, pp. 879–885 (subscription required) Archived 2021-06-06 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

- Archer, William (1930). Play-making: A Manual of Craftsmanship. London: Chapman & Hall. OCLC 1050814206.

- Brockett, Oscar (1982). History of the Theatre. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0-20-507661-1.

- Carlson, Marvin (1984). Theories of the Theatre: A Historical and Critical Survey from the Greeks to the Present. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-80-141678-1.

- Elsom, John (1976). Post-War British Theatre. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-71-008350-0.

- Holroyd, Michael (1997). Bernard Shaw: The One-Volume Definitive Edition. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-6279-5.

- Koon, Helene; Richard Switzer (1980). Eugène Scribe. Boston: Twayne. ISBN 978-0-80-576390-4.

- Lacour, Léopold (1880). Trois Théâtres. Paris: Calmann Levy. OCLC 1986384.

- Rowell, George (2008). "Introduction". Plays by W.S. Gilbert. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-123589-1.

- Shaw, Bernard (1925). The Quintessence of Ibsenism. New York: Brentano. OCLC 1151088484.

- Stanton, Stephen (1956). Camille and Other Plays. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 0809007061.

- Taylor, John Russell (1967). The Rise and Fall of the Well-Made Play. Oxford and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41-572333-6.

- Tolles, Winton (1940). Tom Taylor and the Victorian Drama. New York: Columbia University Press. OCLC 504217641.

- Walkley, A. B. (1925). Still More Prejudice. London: Heinemann. OCLC 1113358388.