Western Chalukya architecture

Western Chalukya architecture (Kannada: ಪಶ್ಚಿಮ ಚಾಲುಕ್ಯ ವಾಸ್ತುಶಿಲ್ಪ), also known as Kalyani Chalukya or Later Chalukya architecture, is the distinctive style of ornamented architecture that evolved during the rule of the Western Chalukya Empire in the Tungabhadra region of modern central Karnataka, India, during the 11th and 12th centuries. Western Chalukyan political influence was at its peak in the Deccan Plateau during this period. The centre of cultural and temple-building activity lay in the Tungabhadra region, where large medieval workshops built numerous monuments.[1] These monuments, regional variants of pre-existing dravida (South Indian) temples, form a climax to the wider regional temple architecture tradition called Vesara or Karnata dravida.[2] Temples of all sizes built by the Chalukyan architects during this era remain today as examples of the architectural style.[3]

_at_Kuruvatti.JPG.webp)

_at_Kubatur.JPG.webp)

Most notable of the many buildings dating from this period are the Mahadeva Temple at Itagi in the Koppal district, the Kasivisvesvara Temple at Lakkundi in the Gadag district, the Mallikarjuna Temple at Kuruvatti in the Bellary district and the Kallesvara Temple at Bagali in the Davangere district.[4][5] Other monuments notable for their craftsmanship include the Kaitabheshvara Temple in Kubatur and Kedareshvara Temple in Balligavi, both in the Shimoga district, the Siddhesvara Temple at Haveri in the Haveri district, the Amrtesvara Temple at Annigeri in the Dharwad district, the Sarasvati Temple in Gadag, and the Dodda Basappa Temple at Dambal, both in the Gadag district.[6]

The surviving Western Chalukya monuments are temples built in the Shaiva, Vaishnava, and Jain religious traditions. None of the military, civil, or courtly architecture has survived; being built of mud, brick and wood, such structures may not have withstood repeated invasions.[7] The centre of these architectural developments was the region encompassing the present-day Dharwad district; it included areas of present-day Haveri and Gadag districts.[8][9] In these districts, about fifty monuments have survived as evidence of the widespread temple building of the Western Chalukyan workshops. The influence of this style extended beyond the Kalyani region in the northeast to the Bellary region in the east and to the Mysore region in the south. In the Bijapur–Belgaum region to the north, the style was mixed with that of the Hemadpanti temples. Although a few Western Chalukyan temples can be found in the Konkan region, the presence of the Western Ghats probably prevented the style from spreading westwards.[8]

Evolution

Though the basic plan of the Western Chalukya style originated from the older dravida style, many of its features were unique and peculiar to it.[10][11] One of these distinguishing features of the Western Chalukyan architectural style was an articulation that can still be found throughout modern Karnataka. The only exceptions to this motif can be found in the area around Kalyani, where the temples exhibit a nagara (North Indian) articulation which has its own unique character.[12]

In contrast to the buildings of the early Badami Chalukyas, whose monuments were clustered around the metropolis of Pattadakal, Aihole, and Badami, these Western Chalukya temples are widely dispersed, reflecting a system of local government and decentralisation.[1] The Western Chalukya temples were smaller than those of the early Chalukyas, a fact discernible in the reduced height of the superstructures which tower over the shrines.[1]

The Western Chalukya art evolved in two phases, the first lasting approximately a quarter of a century and the second from the beginning of 11th century until the end of Western Chalukya rule in 1186 CE. During the first phase, temples were built in the Aihole-Banashankari-Mahakuta region (situated in the early Chalukya heartland) and Ron in the Gadag district. A few provisional workshops built them in Sirval in the Kalaburagi district and Gokak in the Belgaum district. The structures at Ron bear similarities to the Rashtrakuta temples in Kuknur in the Koppal district and Mudhol in the Bijapur district, evidence that the same workshops continued their activity under the new Karnata dynasty.[13] The mature and latter phase reached its peak at Lakkundi (Lokigundi), a principal seat of the imperial court.[14] From the mid-11th century, the artisans from the Lakkundi school moved south of the Tungabhadra River. Thus the influence of the Lakkundi school can be seen in some of the temples of the Davangere district, and in the temples at Hirehadagalli and Huvinahadgalli in the Bellary district.[15]

Influences of Western Chalukya architecture can be discerned in the geographically distant schools of architecture of the Hoysala Empire in southern Karnataka, and the Kakatiya dynasty in present-day Telangana and Andhra Pradesh.[16] Sometimes called the Gadag style of architecture, Western Chalukya architecture is considered a precursor to the Hoysala architecture of southern Karnataka.[17] This influence occurred because the early builders employed by the Hoysalas came from pronounced centres of medieval Chalukya art.[18][19] Further monuments in this style were built not only by the Western Chalukya kings but, also by their feudal vassals.

Temple complexes

Basic layout

A typical Western Chalukya temple may be examined from three aspects – the basic floor plan, the architectural articulation, and the figure sculptures.

The basic floor plan is defined by the size of the shrine, the size of the sanctum, the distribution of the building mass, and by the pradakshina (path for circumambulation), if there is one.[20]

Architectural articulation refers to the ornamental components that give shape to the outer wall of the shrine. These include projections, recesses, and representations that can produce a variety of patterns and outlines, either stepped, stellate (star-shaped), or square.[21] If stepped (also called "stepped diamond of projecting corners"), these components form five or seven projections on each side of the shrine, where all but the central one are projecting corners (projections with two full faces created by two recesses, left and right, that are at right angles with each other). If square (also called "square with simple projections"), these components form three or five projections on a side, only two of which are projecting corners. Stellate patterns form star points which are normally 8-, 16-, or 32-pointed and are sub-divided into interrupted and uninterrupted stellate components. In an 'interrupted' stellate plan, the stellate outline is interrupted by orthogonal (right-angle) projections in the cardinal directions, resulting in star points that have been skipped.[22] Two basic kinds of architectural articulation are found in Indian architecture: the southern Indian dravida and the northern Indian nagara.[23]

Figure sculptures are miniature representations that stand by themselves, including architectural components on pilasters, buildings, sculptures, and complete towers. They are generally categorised as "figure sculpture" or "other decorative features".[24] On occasion, rich figure sculpture can obscure the articulation of a shrine, when representations of gods, goddesses, and mythical figures are in abundance.[25]

Categories

_in_Kalleshvara_temple_at_Bagali_1.JPG.webp)

Chalukyan temples fall into two categories – the first being temples with a common mantapa (a colonnaded hall) and two shrines (known as dvikuta), and the second being temples with one mantapa and a single shrine (ekakuta). Both kinds of temples have two or more entrances giving access to the main hall. This format differs from both the designs of the northern Indian temples, which have a small closed mantapa leading to the shrine and the southern Indian temples which generally have a large, open, columned mantapa.[26]

The Chalukyan architects retained features from both northern and southern styles. However, in the overall arrangement of the main temple and of the subsidiary shrines, they inclined towards the northern style and tended to build one main shrine with four minor shrines, making the structure a panchayatna or five-shrined complex.[27] Chalukyan temples were, almost always, built facing the east.[28]

The Sanctum (cella) is connected by a vestibule (ardha mantapa or ante-chamber) to the closed mantapa (also called the navaranga), which is connected to the open mantapa. Occasionally there can be two or more open mantapas. In Shaiva temples, directly opposite the sanctum and opposite the closed mantapa is the nandi mantapa, which enshrines a large image of Nandi, the bull attendant of Shiva. The shrine usually has no pradakshina.[29]

The pillars that support the roof of the mantapa are monolithic shafts from the base up to the neck of the capital. Therefore, the height of the mantapa and the overall size of the temple were limited by the length of the stone shafts that the architects were able to obtain from the quarries.[30] The height of the temple was also constrained by the weight of the superstructure on the walls and, since Chalukyan architects did not use mortar, by the use of dry masonry and bonding stones without clamps or cementing material.[30]

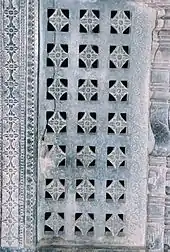

The absence of mortar allows some ventilation in the innermost parts of the temple through the porous masonry used in the walls and ceilings. The modest amount of light entering the temples comes into the open halls from all directions, while the very subdued illumination in the inner closed mantapa comes only through its open doorway. The vestibule receives even less light, making it necessary to have some form of artificial lighting (usually, oil lamps) even during the day. This artificial source of light perhaps adds "mystery" to the image of the deity worshipped in the sanctum.[31]

Early developments

From the 11th century, newly incorporated features were either based on the traditional dravida plan of the Badami Chalukyas, as found in the Virupaksha and Mallikarjuna Temples at Pattadakal, or were further elaborations of this articulation. The new features produced a closer juxtaposition of architectural components, visible as a more crowded decoration, as can be seen in the Mallikarjuna Temple at Sudi in the Gadag district and the Amrtesvara Temple at Annigeri in the Dharwad district.[32]

The architects in the Karnataka region seem to have been inspired by architectural developments in northern India. This is evidenced by the fact that they incorporated decorative miniature towers (multi-aedicular towers depicting superstructures) of the Sekhari and Bhumija types, supported on pilasters, almost simultaneously with these developments in the temples in northern India. The miniature towers represented shrines, which in turn represented deities. Sculptural depictions of deities were generally discreet although not uncommon. Other northern ideas they incorporated were the pillar bodies that appeared as wall projections.[33] Well-known constructions incorporating these features are found at the Kasivisvesvara Temple and the Nannesvara Temple, both at Lakkundi.[34]

In the 11th century, temple projects began employing soapstone, a form of greenish or blueish black stone, although temples such as the Mallikarjuna Temple at Sudi, the Kallesvara Temple at Kuknur, and the temples at Konnur and Savadi were built with the formerly traditional sandstone in the dravida articulation.[32]

Soapstone is found in abundance in the regions of Haveri, Savanur, Byadgi, Motebennur and Hangal. The great archaic sandstone building blocks used by the Badami Chalukyas were superseded with smaller blocks of soapstone and with smaller masonry.[35] The first temple to be built from this material was the Amrtesvara Temple in Annigeri in the Dharwad district in 1050 CE. This building was to be the prototype for later, more articulated structures such as the Mahadeva Temple at Itagi.[36]

Soapstone was also used for carving, modelling and chiselling of components that could be described as "chubby".[37] However, the finish of the architectural components compared to the earlier sandstone temples is much finer, resulting in opulent shapes and creamy decorations.[38] Stepped wells are another feature that some of the temples included.[39]

Later enhancements

The 11-century temple-building boom continued in the 12th century with the addition of new features. The Mahadeva Temple at Itagi and the Siddhesvara Temple in Haveri are standard constructions incorporating these developments. Based on the general plan of the Amrtesvara Temple at Annigeri, the Mahadeva Temple was built in 1112 CE and has the same architectural components as its predecessor. There are however differences in their articulation; the sala roof (roof under the finial of the superstructure) and the miniature towers on pilasters are chiseled instead of moulded.[40] The difference between the two temples, built fifty years apart, is the more rigid modelling and decoration found in many components of the Mahadeva Temple. The voluptuous carvings of the 11th century were replaced with a more severe chiselling.[41]

As developments progressed, the Chalukyan builders modified the pure dravida tower by reducing the height of each stepped storey and multiplying their number. From base to top, the succeeding storeys get smaller in circumference and the topmost storey is capped with a crown holding the kalasa, a finial in the shape of a decorative water pot. Each storey is so richly decorated that the original dravida character becomes almost invisible. In the nagara tower the architects modified the central panels and niches on each storey, forming a more-or-less continuous vertical band and simulating the vertical bands up the centre of each face of the typical northern style tower.[35] Old and new architectural components were juxtaposed but introduced separately.[40] Some superstructures are essentially a combination of southern dravida and northern nagara structures and is termed "Vesara Shikhara" (also called Kadamba Shikhara).[29]

The characteristically northern stepped-diamond plan of projecting corners was adopted in temples built with an entirely dravida articulation.[37] Four 12th century structures constructed according to this plan are extant: the Basaveshwara Temple at Basavana Bagevadi, the Ramesvara Temple at Devur and the temples at Ingleshwar and Yevur, all in the vicinity of the Kalyani region, where nagara temples were common. This plan came into existence in northern India only in the 11th century, a sign that architectural ideas traveled fast.[42]

Stellate plans

A major development of this period was the appearance of stellate (star-shaped) shrines in a few temples built of the traditional sandstone, such as the Trimurti Temple at Savadi, the Paramesvara Temple at Konnur and the Gauramma Temple at Hire Singgangutti. In all three cases, the shrine is a 16-pointed uninterrupted star, a ground-plan not found anywhere else in India and which entirely differentiates these temples from the 32-pointed interrupted star plans of bhumija shrines in northern India.[43]

The stellate plan found popularity in the soapstone constructions such as the Doddabasappa Temple at Dambal as well. Contemporary stellate plans in northern India were all 32-pointed interrupted types. No temples of the 6-, 12-, or 24-pointed stellate plans are known to exist anywhere in India, with the exception of the unique temple at Dambal, which can be described either as a 24-pointed uninterrupted plan, or a 48-pointed plan with large square points of 90 degrees alternating with small short points of 75 degrees.[44] The upper tiers of the seven-tiered superstructure look like cogged wheels with 48 dents.[45] The Doddabasappa Temple and the Someshvara Temple at Lakshmeshwara are examples of extreme variants of a basic dravida articulation. These temples prove that the architects and craftsman were consciously creating new compositions of architectural components out of traditional methods.[46]

In the early 13th century, 12th century characteristics remained prominent; however, many parts that were formerly plain became decorated. This change is observed in the Muktesvara Temple at Chaudayyadanapura (Chavudayyadanapura) and the Santesvara Temple at Tilavalli, both in the Haveri district. The Muktesvara Temple with its elegant vimana was renovated in the middle of the 13th century.[47] In the Tilavalli Temple, all the architectural components are elongated, giving it an intended crowded look. Both temples are built with a dravida articulation.[47] Apart from exotic dravida articulations, some temples of this period have nagara articulation, built in the stepped-diamond and the square plan natural to a nagara superstructure. Notable among temples with a stepped-diamond style are the Ganesha Temple at Hangal, the Banashankari temple at Amargol (which has one dravida shrine and one nagara shrine), and a small shrine that is a part of the ensemble at the Mahadeva Temple.[45] At Hangal, the architects were able to provide a sekhari superstructure to the shrine, while the lower half received a nagara articulation and depictions of miniature sekhari towers. The style of workmanship with a square plan is found at Muttagi and the Kamala Narayana Temple at Degoan.[45]

Kalyani region

Temples built in and around the Kalyani region (in the Bidar district) were quite different from those built in other regions. Without exception, the articulation was nagara, and the temple plan as a rule was either stepped-diamond or stellate.[22] The elevations corresponding to these two plans were similar because star shapes were produced by rotating the corner projections of a standard stepped plan in increments of 11.25 degrees, resulting in a 32-pointed interrupted plan in which three star points are skipped in the centre of each side of the shrine.[22] Examples of stepped-diamond plans surviving in Karnataka are the Dattatreya Temple at Chattarki, the Someshvara Temple in Kadlewad, and the Mallikarjuna and Siddhesvara at Kalgi in the Gulbarga district. The nagara shrine at Chattarki is a stepped diamond of projecting corners with five projections per side.[22] Because of the stepped-diamond plan, the wall pillars have two fully exposed sides, with a high base block decorated with a mirrored stalk motif and two large wall images above. The shapes and decorations on the rest of the wall pillar have a striking resemblance to the actual pillars supporting the ceiling.[48]

The other type is the square plan with simple projections and recesses but with a possibility of both sekhari and bhumija superstructures. The plan does not have any additional elements save those that derive from the ground plan. The recesses are simple and have just one large wall image. The important characteristic of these nagara temples in the Kalyani region is that they not only differ from the dravida temples in the north Karnataka region but from the nagara temples north of the Kalyani region as well. These differences are manifest in the articulation and in the shapes and ornamentation of individual architectural components, giving them a unique place in Chalukyan architecture. Temples that fall in this category are the Mahadeva Temple at Jalsingi and the Suryanarayana Temple at Kalgi in the modern-day Kalaburagi district.[48] The plan and the nagara articulation of these temples are the same as found to the north of the Kalyani region, but the details are different, producing a different look.[12]

Architectural elements

Overview

The Western Chalukya decorative inventiveness focused on the pillars, door panels, lintels (torana), domical roofs in bays,[49] outer wall decorations such as Kirtimukha (gargoyle faces common in Western Chalukya decoration),[50][51] and miniature towers on pilasters.[30] Although the art form of these artisans does not have any distinguishing features from a distance, a closer examination reveals their taste for decoration. An exuberance of carvings, bands of scroll work, figural bas-reliefs and panel sculptures are all closely packed.[52] The doorways are highly ornamented but have an architectural framework consisting of pilasters, a moulded lintel and a cornice top. The sanctum receives diffused light through pierced window screens flanking the doorway; these features were inherited and modified by the Hoysala builders.[29] The outer wall decorations are well rendered. The Chalukyan artisans extended the surface of the wall by means of pilasters and half pilasters. Miniature decorative towers of multiple types are supported by these pilasters. These towers are of the dravida tiered type, and in the nagara style they were made in the latina (mono aedicule) and its variants; the bhumija and sekhari.[53]

Vimana

The Jain Temple, Lakkundi marked an important step in the development of Western Chalukya outer wall ornamentation, and in the Muktesvara Temple at Chavudayyadanapura the artisans introduced a double curved projecting eave (chhajja), used centuries later in Vijayanagara temples.[33] The Kasivisvesvara Temple at Lakkundi embodies a more mature development of the Chalukyan architecture in which the tower has a fully expressed ascending line of niches. The artisans used northern style spires and expressed it in a modified dravida outline. Miniature towers of both dravida and nagara types are used as ornamentation on the walls. With further development, the divisions between storeys on the superstructure became less marked, until they almost lost their individuality. This development is exemplified in the Dodda Basappa Temple at Dambal, where the original dravida structure can only be identified after reading out the ornamental encrustation that covers the surface of each storey.[27]

The walls of the vimana below the dravida superstructure are decorated with simple pilasters in low relief with boldly modeled sculptures between them. There are fully decorated surfaces with frequent recesses and projections with deeper niches and conventional sculptures.[52] The decoration of the walls is subdued compared to that of the later Hoysala architecture. The walls, which are broken up into hundreds of projections and recesses, produce a remarkable effect of light and shade,[52] an artistic vocabulary inherited by the Hoysala builders in the decades that followed.[54]

Mantapa

An important feature of Western Chalukya roof art is the use of domical ceilings (not to be confused with the European types that are built of voussoirs with radiating joints) and square ceilings. Both types of ceilings originate from the square formed in the ceiling by the four beams that rest on four pillars. The dome above the four central pillars is normally the most attractive.[26] The dome is constructed of ring upon ring of stones, each horizontally bedded ring smaller than the one below. The top is closed by a single stone slab. The rings are not cemented but held in place by the immense weight of the roofing material above them pressing down on the haunches of the dome.[26] The triangular spaces created when the dome springs from the centre of the square are filled with arabesques. In the case of square ceilings, the ceiling is divided into compartments with images of lotus rosettes or other images from Hindu mythology.[26]

Pillars are a major part of Western Chalukya architecture and were produced in two main types: pillars with alternate square blocks and a sculptured cylindrical section with a plain square-block base, and bell-shaped lathe-turned pillars. The former type is more vigorous and stronger than the bell-shaped type, which is made of soapstone and has a quality of its own.[30] Inventive workmanship was used on soapstone shafts, roughly carved into the required shapes using a lathe. Instead of laboriously rotating a shaft to obtain the final finish, workers added the final touches to an upright shaft by using sharp tools. Some pillars were left unpolished, as evidenced by the presence of fine grooves made by the pointed end of the tool. In other cases, polishing resulted in pillars with fine reflective properties such as the pillars in the temples at Bankapura, Itagi and Hangal.[30] This pillar art reached its zenith in the temples at Gadag, specifically the Sarasvati Temple in Gadag city.[55]

Notable in Western Chalukya architecture are the decorative door panels that run along the length of the door and over on top to form a lintel. These decorations appear as bands of delicately chiseled fretwork, moulded colonettes and scrolls scribed with tiny figures. The bands are separated by deep narrow channels and grooves and run over the top of the door.[26] The temple plan often included a heavy slanting cornice of double curvature, which projected outward from the roof of the open mantapa. This was intended to reduce heat from the sun, blocking the harsh sunlight and preventing rainwater from pouring in between the pillars.[56] The underside of the cornice looks like woodwork because of the rib-work. Occasionally, a straight slabbed cornice is seen.[56]

Sculpture

Figure sculpture

Figural sculpture on friezes and panels changed during the period. The heroes from the Hindu epics Ramayana and Mahabharata, depicted often in early temples, become fewer, limited to only a few narrow friezes; there is a corresponding increase in the depiction of Hindu gods and goddesses in later temples.[57] Depiction of deities above miniature towers in the recesses, with a decorative lintel above, is common in 12th-century temples, but not in later ones.[41] Figures of holy men and dancing girls were normally sculpted for deep niches and recesses. The use of bracket figures depicting dancing girls became common on pillars under beams and cornices. Among animal sculptures, the elephant appears more often than the horse: its broad volumes offered fields for ornamentation.[57] Erotic sculptures are rarely seen in Chalukyan temples; the Tripurantakesvara Temple at Balligavi is an exception. Here, erotic sculpture is limited to a narrow band of friezes that run around the exterior of the temple.[58]

Deity sculpture

In what was a departure from convention, the Western Chalukyan figure sculptures of gods and goddesses bore stiff forms and were repeated over and over in the many temples.[56] This was in contrast to the naturalistic and informal poses employed in the earlier temples in the region. Barring occasional exaggerations in pose, each principal deity had its own pose depending on the incarnation or form depicted. Consistent with figure sculpture in other parts of India, these figures were fluent rather than defined in their musculature, and the drapery was reduced to a few visible lines on the body of the image.[56]

Western Chalukyan deity sculptures were well-rendered; exemplified best by that of Hindu goddess Sarasvati at the Sarasvati temple in Gadag city.[59] Much of the drapery on the bust of the image is ornamentation comprising jewellery made of pearls around her throat. An elaborate pile of curls forms her hair, some of which trails to her shoulders. Above these curly tresses and behind the head is a tiered coronet of jewels, the curved edge of which rises to form a halo.[60] From the waist down, the image is dressed in what seems to be the most delicate of material; except for the pattern of embroidery traced over it, it is difficult to tell where the drapery begins and where it ends.[61]

Miniature towers

From the 11th century, architectural articulation included icons between pilasters, miniature towers supported by pilasters in the recesses of walls, and, on occasion, the use of wall pillars to support these towers.[33] These miniature towers were of the southern dravida and northern bhumija and sekhari types and were mostly used to elaborate dravida types of articulation. The miniatures on single pilasters were decorated with a protective floral lintel on top, a form of decoration normally provided for depiction of gods.[38] These elaborations are observed in the Amrtesvara Temple at Annigeri. These miniatures became common in the 12th century, and the influence of this northern articulation is seen in the Kasivisvesvara Temple at Lakkundi and in the nearby Nannesvara Temple.[33]

The miniature towers bear finer and more elegant details, indicating that architectural ideas traveled fast from the north to the south.[62] Decoration and ornamentation had evolved from a moulded form to a chiseled form, the sharpness sometimes giving it a three-dimensional effect. The foliage decorations changed from bulky to thin, and a change in the miniature towers on dual pilasters is seen. The 11th century miniatures consisted of a cornice (kapota), a floor (vyalamala), a balustrade (vedika) and a roof (kuta) with a voluptuous moulding, while in the 12th century, detailed dravida miniature towers with many tiny tiers (tala) came into vogue.[41] Some 12th-century temples such as the Kallesvara Temple at Hirehadagalli have miniature towers that do not stand on pilasters but instead are supported by balconies, which have niches underneath that normally contain an image of a deity.[63]

Temple deities

The Western Chalukyan kings Shaivas (worshippers of the Hindu god Shiva) dedicated most of their temples to that God. They were however tolerant of the Vaishnava or Jain faiths and dedicated some temples to Vishnu and the Jain tirthankaras respectively. There are some cases where temples originally dedicated to one deity were converted to suit another faith. In such cases, the original presiding deity can sometimes still be identified by salient clues. While these temples shared the same basic plan and architectural sensibilities, they differed in some details, such as the visibility and pride of place they afforded the different deities.[26]

_Brahma_image_in_the_mantapa_in_the_Jain_temple_at_Lakkundi.jpg.webp)

As with all Indian temples, the deity in the sanctum was the most conspicuous indicator of the temple's dedication. The sanctum (Garbhagriha or cella) of a Shaiva temple would contain a Shiva linga, the universal symbol of the deity.[64] An image of Gaja Lakshmi (consort of the Hindu god Vishnu) or an image of Vishnu riding on Garuda, or even just the Garuda, signifies a Vaishnava temple. Gaja Lakshmi, however, on account of her importance to the Kannada-speaking regions,[26] is found on the lintel of the entrance to the mantapa (pillared hall) in all temples irrespective of faith. The carving on the projecting lintel on the doorway to the sanctum has the image of a linga or sometimes of Ganapati (Ganesha), the son of Shiva in the case of Shaiva temples or of a seated or upright Jain saint (Tirthankar) in the case of Jain temples.[26]

The sukanasi or great arched niche at the base of the superstructure (Shikhara or tower) also contains an image indicative of the dedicators' sect or faith.[26] Above the lintel, in a deep and richly wrought architrave can be found images of the Hindu trimurti (the Hindu triad of deities) Brahma, Shiva and Vishnu beneath arched rolls of arabesque. Shiva or Vishnu occupies the centre depending on the sect the temple was dedicated to.[26]

Occasionally, Ganapati and his brother Kartikeya (Kumara, Subramanya) or the saktis, the female counterparts, can be found at either end of this carving. Carvings of the river Goddesses Ganga and Yamuna are found at either end of the foot of the doorway to the shrine in early temples.[30]

Appreciation

Influence

The Western Chalukya dynastic rule ended in the late 12th century, but its architectural legacy was inherited by the temple builders in southern Karnataka, a region then under the control of the Hoysala empire.[65] Broadly speaking, Hoysala architecture is derived from a variant of Western Chalukya architecture that emerged from the Lakshmeshwar workshops.[66] The construction of the Chennakesava Temple at Belur was the first major project commissioned by Hoysala King Vishnuvardhana in 1117 CE. This temple best exemplifies the Chalukyan taste the Hoysala artisans inherited. Avoiding overdecoration, these artists left uncarved spaces where required, although their elaborate doorjambs are exhibitionistic. Here, on the outer walls, the sculptures are not overdone, yet they are articulate and discreetly aesthetic.[18][67] The Hoysala builders used soapstone almost universally as building material, a trend that started in the middle of the 11th century with Chalukyan temples.[32] Other common artistic features between the two Kanarese dynasties are the ornate Salabhanjika (pillar bracket figures), the lathe-turned pillars and the makara torana (lintel with mythical beastly figure).[18] The tower over the shrine in a Hoysala temple is a closely moulded form of the Chalukya style tower.[68]

When the Vijayanagara Empire was in power in the 15th and 16th centuries, its workshops preferred granite over soapstone as the building material for temples. However, an archaeological discovery within the royal center at Vijayanagara has revealed the use of soapstone for stepped wells. These stepped wells are fashioned entirely of finely finished soapstone arranged symmetrically, with steps and landings descending to the water on four sides. This design shows strong affinities to the temple tanks of the Western Chalukya–Hoysala period.[69]

Research

Unlike the Badami Chalukyan temples featured in detailed studies by Henry Cousens (1927), Gary Tartakov (1969) and George Michell (1975), Western Chalukyan architecture suffered neglect despite its importance and wider use. Recently however, scholars have returned to the modern Karnataka region to focus on a longer chronology, investigating a larger geographical area, making detailed studies of epigraphs and giving more importance to individual monuments dating from the 11th through 13th centuries.[2]

The first detailed study of Western Chalukya architecture was by M.A. Dhaky (1977), who used as a starting point two medieval epigraphs that claimed the architects were masters of various temple forms. This study focused in particular on the riches of the Western Chalukya miniature wall shrines (aedicules). An important insight gained from this work was that the architects of the region learned about temple forms from other regions. These forms to them appeared "exotic", but they learned to reproduce them with more or less mastery, depending on the extent of their familiarity with the other regions' building traditions.[70] This conscious eclectic attempt to freely use elements from other regions in India was pointed out by Sinha (1993) as well.[71]

A seminal work by Adam Hardy (1995) examined the Karnataka temple-building tradition over a period of 700 years, from the 7th century to the 13th century, and reviewed more than 200 temples built by four dynasties; Badami Chalukya, Rashtrakuta, Western Chalukya and Hoysala. The study covered dravida and nagara style monuments and the differences between the dravida tradition in modern Karnataka and that of neighbouring Tamil Nadu and made it possible to interpret the many architectural details as part of a larger scheme.[2][71]

The temples and epigraphs of the Western Chalukyas are protected by the Archaeological Survey of India and the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums–Government of Karnataka.[72][73] In the words of historian S. Kamath (2001), "The Western Chalukyas left behind some of the finest monuments of artistic merit. Their creations have the pride of place in Indian art tradition".[17]

Notable temples

The Mahadeva Temple at Itagi dedicated to Shiva is among the larger temples built by the Western Chalukyas and perhaps the most famous. Inscriptions hail it as the 'Emperor among temples'.[74] Here, the main temple, the sanctum of which has a linga, is surrounded by thirteen minor shrines, each with its own linga. The temple has two other shrines, dedicated to Murthinarayana and Chandraleshwari, parents of Mahadeva, the Chalukya commander who consecrated the temple in 1112 CE.[75]

The Siddheshwara temple in the Haveri district has sculptures of deities of multiple faiths. The temple may have been consecrated first as a Vaishnava temple, later taken over by Jains and eventually becoming a Shaiva temple.[28] The hall in the temple contains sculptures of Uma Mahesvara (Shiva with his consort Uma), Vishnu and his consort Lakshmi, Surya (the sun god), Naga-Nagini (the snake goddess), and the sons of Shiva, Ganapati and Kartikeya. Shiva is depicted with four arms, holding his attributes: the damaru (drum), the aksamala (chain of beads) and the trishul (trident) in three arms. His lower left arm rests on Uma, who is seated on Shiva's lap, embracing him with her right arm while gazing into his face. The sculpture of Uma is well decorated with garlands, large earrings and curly hair.[76]

Some temples, in a departure from the norm, were dedicated to deities other than Shiva or Vishnu. These include the Surya (portrayed as 'Suryanarayana') shrine at the Kasi Vishveshwara temple complex and a Jain temple dedicated to Mahavira, both at Lakkundi; the Taradevi temple (built in a Buddhist architectural style) at Dambal in the Gadag district; the Mahamaya temple dedicated to a tantric goddess at Kuknur in the Koppal district, and the Durga temple at Hirekerur in the Haveri district.[77]

See also

Notes

- Hardy (1995), p 156

- Sinha, Ajay J. (1999). "Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation, the Karṇāṭa Drāviḍa Tradition, 7th to 13th Centuries by Adam Hardy". Artibus Asiae. 58 (3/4): 358–362. doi:10.2307/3250027. JSTOR 3250027.

- Hardy (1995), pp 6–7

- Hardy (1995), p323, p333, p335, p336

- The Mahadeva Temple at Itagi has been called the finest in Kannada country after the Hoysaleswara temple at Halebidu (Cousens in Kamath (2001), p 117)

- Hardy (1995), p321, p326, p327, p330, p335

- Cousens (1926), p 27

- Cousens (1926, p 17

- Foekema (1996), p 14

- The original dravida temple plans had evolved during the 6th and 7th centuries in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu under the Badami Chalukyas and Pallava empires. (Foekema 1996, p 11)

- The development of pure dravida art was a result of parallel, interrelated developments in the modern Karnataka and Tamil Nadu regions, within a broader context of South Indian art (Hardy 1995, p 12)

- Foekema (2003), p 65

- Hardy (1995), p 157

- Hardy (1995), p 158

- Hardy (1995), p 217

- Hardy (1995), p 215

- Kamath (2001), p 115

- Kamath (2001), p 118

- Settar S. "Hoysala Heritage". Frontline, Volume 20, Issue 08, April 12–25, 2003. Frontline, From the publishers of the Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 July 2006. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- Foekema (2003), p 47

- Foekema (2003), pp 35, 47

- Foekema (2003), p 63

- Foekema (2003), p 42

- Foekema (2003), pp 35, 37, 48

- Foekema (2003), p 37

- Cousens (1926), p 22

- Cousens (1926), p 19

- Cousens (1926), p 85

- Kamath (2001), p 116

- Cousens (1926), p 23

- Cousens (1926), p 21

- Foekema (2003), p 50

- Foekema (2003), p 51

- Foekema (2003), p 51, p 53

- Cousens (1926), p 18

- Foekema (2003), p 49

- Foekema (2003), p 55

- Foekema (2003), p 52

- Kamiya, Takeo (20 September 1996). "Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent". Gerard da Cunha-Architecture Autonomous, Bardez, Goa, India. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- Foekema (2003), p 57

- Foekema (2003), p 56

- Foekema (2003), pp 54–55

- Foekema (2003), pp 53–54

- Foekema (2003), p 60

- Foekema (2003), p 61

- Foekema (2003), pp 58–59

- Foekema (2003), p 58

- Foekema (2003), p 64

- A square or rectangular compartment in a hall (Foekema 1996, p 93)

- The face of a monster used as decoration in Hindu temples (Foekema 1996, p 93)

- Kamiya, Takeo (20 September 1996). "Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent". Gerard da Cunha-Architecture Autonomous, Bardez, Goa, India. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- Cousens (1926), p 20

- Kamath (2001), p 117

- Settar S. "Hoysala Heritage". Frontline, Volume 20 – Issue 08, April 12–25, 2003. Frontline, From the publishers of the Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 July 2006. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- Kannikeswaran. "Templenet Encyclopedia – Temples of Karnataka, Kalyani Chalukyan temples". Retrieved 16 December 2006.

- Cousens (1926), p 24

- Cousens (1926), p 26

- Cousens (1926), p 107

- Cousens (1926), p 78

- Cousens (1926), pp 25–26

- Cousens (1926), pp 24–25

- Foekema (2003), p 53

- Foekema (2003), p 59

- Foekema (1996), p 93

- Kamath (2001), pp 115, 134

- Hardy (1995), p 243

- Settar S. "Hoysala Heritage". Frontline, Volume 20 – Issue 08, April 12–25, 2003. Frontline, From the publishers of the Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 July 2006. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

- Sastri (1955), p 427

- Davison–Jenkins (2001), p 89

- Foekema (2003), p 12

- Foekema (2003), p 31

- "Alphabetical list of Monuments". Protected Monuments. Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 8 August 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2007.

- "Directory of Monuments in Karnataka". Department of Archaeology and Museums–Archaeological Monuments. National Informatics Centre, Karnataka. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- Kamath (2001), pp 117–118

- Rao, Kishan (10 June 2002). "Emperor of Temples' crying for attention". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 November 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Nagaraja Rao, M. S. (1969). "Sculptures from the Later Cālukyan Temple at Hāveri". Artibus Asiae. 31 (2/3): 167–178. doi:10.2307/3249429. JSTOR 3249429.

- K. Kannikeswaran. "Templenet Encyclopedia, The Ultimate Source of Information on Indian Temples". Kalyani Chalukyan Temples. Retrieved 10 November 2007.

References

Book

- Cousens, Henry (1996) [1926]. The Chalukyan Architecture of Kanarese Districts. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India. OCLC 37526233.

- Foekema, Gerard (2003) [2003]. Architecture decorated with architecture: Later medieval temples of Karnataka, 1000–1300 AD. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 81-215-1089-9.

- Foekema, Gerard (1996). A Complete Guide To Hoysala Temples. New Delhi: Abhinav. ISBN 81-7017-345-0.

- Hardy, Adam (1995) [1995]. Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation-The Karnata Dravida Tradition 7th to 13th Centuries. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-312-4.

- Jenkins, Davison (2001). "Hydraulic Works". In John M. Fritz; George Michell (eds.). New Light on Hampi: Recent Research at Vijayanagara. Mumbai: MARG. ISBN 81-85026-53-X.

- Kamath, Suryanath U. (2001) [1980]. A concise history of Karnataka : from pre-historic times to the present. Bangalore: Jupiter books. LCCN 80905179. OCLC 7796041.

- Sastri, Nilakanta K.A. (2002) [1955]. A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar. New Delhi: Indian Branch, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-560686-8.

- Sinha, Ajay J. (1999). "Review of Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation, the Karṇāṭa Drāviḍa Tradition, 7th to 13th Centuries by Adam Hardy". Artibus Asiae. 58 (3/4): 358–362. doi:10.2307/3250027. JSTOR 3250027.

Web

- "Alphabetical List of Monuments – Karnataka". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 8 August 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- Kamat J. "Temples of Karnataka". Timeless Theater – Karnataka. Kamat's Potpourri. Retrieved 30 December 2007.

- Kamiya, Takeyo. "Architecture of Indian subcontinent". Indian Architecture. Gerard da Cunha. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- Kannikeswaran K. "Templenet-Kalyani Chalukyan temples". Temples of Karnataka. www.templenet.com. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- Rao, Kishan. "Emperor of Temples' crying for attention". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 November 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Rao, M. S. Nagaraja (1969). "Sculptures from the Later Cālukyan Temple at Hāveri". Artibus Asiae. 31 (2/3): 167–178. doi:10.2307/3249429. JSTOR 3249429.

- Settar S. "Hoysala heritage". history and craftsmanship of Belur and Halebid temples. Frontline. Archived from the original on 1 July 2006. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- "Directory of Monuments in Karnataka-Government of Karnataka". Directorate of Archaeology and Museums. National Informatics Centre, Karnataka. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

External links

- "Speaks of catholic outlook". The hindu. 11 May 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2013.