What Are The Theosophists?

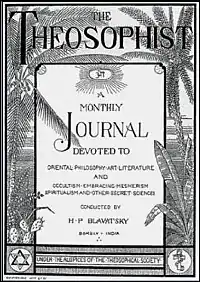

"What Are The Theosophists?" is an editorial published in October 1879 in the theosophical magazine The Theosophist. It was compiled by Helena Blavatsky[note 1] and it was included the second volume of the Blavatsky Collected Writings.[2]

Analysis of contents

Accusations and accusers

Arnold Kalnitsky wrote in his thesis[3] that in this article "we find a rather expansive statement of... [Blavatsky's] thoughts at that moment about the status of the movement, the Theosophical Society, its objectives, and the issues it was confronting." He wrote that the article begins with a question whether the Theosophists "are they what they claim to be": researchers of the laws of nature, ancient and modern philosophy, and science.[4] Blavatsky asks:

"Are they Deists, Atheists, Socialists, Materialists, or Idealists; or are they but a schism of modern Spiritualism,—mere visionaries?"[5]

The thesis' author has written that author of the article lists some of the allegations brought against the Theosophical movement, and calls several accusers of the Theosophists. This is the "miracle-working;" and a work as "spies of an autocratic Czar;" and propaganda of socialist and nihilistic doctrines; and collusion "with the French Jesuits" to discredit modern Spiritualism for money. The American Positivists call the Theosophists with dreamers, the New York journalists call them fetishists, the Spiritualists say they are revivers of superstitions, the servants of the Christian Church call them unbelieving messengers of Satan, professor Carpenter argues that they are silly and gullible persons, and some of their Hindu opponents have accused them "with the employment of demons to perform certain phenomena."[5] Kalnitsky has quoted her assessment of all this:

"One fact stands conspicuous—the Society, its members, and their views, are deemed of enough importance to be discussed and denounced: Men slander only those whom they hate—or fear."[6]

Support of friends

Kalnitsky wrote that Blavatsky, having characterized the opponents of the movement at first, then notes that Theosophy, to a certain extent, relies on "public support and respect." In his opinion, she tries to create the impression that there is an equal ratio between the supporters and opponents of the Theosophists: "But, if the Society has had its enemies and traducers, it has also had its friends and advocates. For every word of censure, there has been a word of praise."[6][note 3] Kalnitsky wrote to show the presence of a positive attitude towards the Theosophists, Blavatsky refers to the "exponential growth of membership" in the Theosophical Society and to the expansion of its geography. As examples of the recognition of Theosophy as a serious undertaking, she speaks of an alliance, albeit "short-lived", with the Indian Society of Arya Samaj,[note 4] and of the fraternal connection with the Ceylon Buddhists.[note 5] According to this thesis, partial acceptance of the Theosophical doctrine by Hindus and Buddhist organizations was an important factor in the propaganda of the movement demonstrated that it really is "something tangible and legitimate", which is embodying the beliefs represented in the eastern traditions of ancient India.[12][note 6] Kalnitsky has quoted the article:

"None is older than she in esoteric wisdom and civilization, however fallen may be her poor shadow—modern India. Holding this country, as we do, for the fruitful hot-bed whence proceeded all subsequent philosophical systems, to this source of all psychology and philosophy a portion of our Society has come to learn its ancient wisdom and ask for the impartation of its weird secrets."[15][note 7]

Free researchers

In his thesis Kalnitsky cited a passage where Blavatsky explains that the Theosophical Society is completely free from personal preferences and "sectarian" interests:

"Having no accepted creed, our Society is very ready to give and take, to learn and teach, by practical experimentation, as opposed to mere passive and credulous acceptance of enforced dogma. It is willing to accept every result claimed by any of the foregoing schools or systems that can be logically and experimentally demonstrated. Conversely, it can take nothing on mere faith, no matter by whom the demand may be made."[17]

The thesis' author commented that this idealized position of Blavatsky should "lead the reader" to the conclusion that the Theosophical Society is an "equivalent" of a scientific research organization, where the main criterion is "logic and experimental verification", not dogma and blind faith. There is here no definite desire to uncompromisingly replace the purely intellectual and rationalist approach with an orientation only to something "spiritual and paranormal". It is assumed that the mystical and occult positions of Theosophy can "ultimately be verified and confirmed" by methods acceptable to "the foregoing schools or systems". Kalnitsky noted that the article author seeks to destroy the authority of the "dogmatic, rationalistic and materialistic" worldviews. She believes that the "contents of knowledge" obtained through esoteric methods are "fully capable" of satisfying the empirical and logical "standards of verifiability." Author of the article reminds the reader that many members of the Society belong to different races and nationalities, have different education and faith, but interest in "magic, spiritualism, mesmerism, occultism" is the basis for bringing together people who are sympathetic to Theosophy.[note 8][note 9] The thesis' author wrote that, in Blavatsky's opinion, even some supporters of the theoretical materialism can be accepted as members of the Society if they are sufficiently objective to recognize that "spiritual principles" can actually abolish the "limited conceptions of orthodox science." Nevertheless, in the Society there can be no place for atheists or fanatical sectarians of any religion.[20] A Ukrainian philosopher Julia Shabanova[21] wrote that, in Blavatsky's opinion, the genuine Theosophists should have faith in the intangible, omnipotent, omnipresent, and invisible Cause, which "is All, and Nothing; ubiquitous yet one; the Essence filling, binding, bounding, containing everything; contained in all."[22]

Blavatsky believes that "the very fact of a man's joining it proves that he is in search of the final truth as to the ultimate essence of things" and that the very character of the idea of the Theosophical Society consists in the "free and fearless investigation."[23][note 10] Kalnitsky and Shabanova have quoted the article as follows:

"It will, we think, be seen now, that whether classed as Theists, Pantheists or Atheists, such men are near kinsmen to the rest. Be what he may, once that a student abandons the old and trodden highway of routine, and enters upon the solitary path of independent thought—Godward—he is a Theosophist; an original thinker, a seeker after the eternal truth with 'an inspiration of his own' to solve the universal problems."[25]

The article's author explains that charter of the Theosophical Society was written in the image and likeness of the Constitution of the United States of America, the country where it was born. She writes that "the Society, modelled upon this Constitution, may fairly be termed a 'Republic of Conscience'."[26]

Kalnitsky wrote that Blavatsky assigns to Theosophy a special supreme status, which does not depend on any misconduct committed by "individual members of the organization." She believes that the Theosophical Society is "potentially a more effective institution" than any scientific or religious organization. "Unlike sectarian religions", Theosophy is not obsessed with differences, because it is based on the "principle of universal brotherhood." Ultimately, the Theosophical ideals and goals surpass any "existing ideologies and social movements." Therefore, Theosophy stands for a voluntarily accepted and approved "spiritual orientation." Thus, according to the Theosophical view, universal brotherhood must become the "logical and inevitable result" of life. Kalnitsky noted that, according to the article author, all modern social positions are unsatisfactory and limited, based "on partial and incomplete" ideas and beliefs that do not have genuine "spiritual legitimacy."[27] He quoted:

"Unconcerned about politics; hostile to the insane dreams of Socialism and of Communism, which it abhors—as both are but disguised conspiracies of brutal force and sluggishness against honest labour; the Society cares but little about the outward human management of the material world. The whole of its aspirations are directed towards the occult truths of the visible and invisible worlds. Whether the physical man be under the rule of an empire or a republic, concerns only the man of matter. His body may be enslaved; as to his Soul, he has the right to give to his rulers the proud answer of Socrates to his judges. They have no sway over the inner man."[28][note 11]

Theoretically, Theosophy was allegedly apolitical, as Kalnitsky noted, and did not concern external human control in "the material world." This was the official course, "motivated by the ideal of spiritual priorities" that went beyond the worldly worries. Although in fact, the persons involved in the Theosophical movement often had different opinions on specific problems. For example, the English and the German Theosophists occupied completely "different positions on the occult significance" of the events of the First World War. However, Blavatsky believed that the true Theosophist should be separated "from the mainstream" of social activity and related ambitions.[30][note 12] Kalnitsky cited her words:

"The true student has ever been a recluse, a man of silence and meditation. With the busy world his habits and tastes are so little in common that, while he is studying, his enemies and slanderers have undisturbed opportunities. But time cures all and lies are but ephemera. Truth alone is eternal."[32]

Kalnitsky wrote that Blavatsky believes that a true researcher is a recluse who does not pay attention to "his enemies and slanderers", who belong in the busy world. Nevertheless, not all researchers need to be represented this way. She mentions the contribution of some members of the Society to science, in particular to "biology and psychology", and the fact that there must be a "diversity in opinion" in science. In an attempt to explain the contradictory public statements made by the Theosophists, "she notes that even great Theosophical thinkers" can sometimes make mistakes and make unsuccessful comments. Such misses "may tarnish their reputations", but this do not detract from their efforts. The desire to change the usual ways of thinking requires the collective action of those who are ready to challenge the current situation and promote a more attractive and "believable alternative system of truth."[33] In conclusion, the article's author writes:

"The attainment of these objects, all agree, can best be secured by convincing the reason and warming the enthusiasm of the generation of fresh young minds, that are just ripening into maturity, and making ready to take the place of their prejudiced and conservative fathers."[34]

Theosophists as an object of criticism

Peter Washington stated that ideas of the Theosophical Society had often attracted all sorts of neurotics, hysterics and even madmen:

"All organisations which depend on enthusiasm and opposition to conventional opinion suffer from this problem to some degree; Theosophy appears to have been especially prone to it. The permanent residents at Adyar during the 1880s and '90s were typical. A quarrelsome collection of minor English aristocrats, rich American widows, German professors, Indian mystics and hangerson of every description, they were all eager to have their say, especially during Olcott's prolonged absences, and all ready to quarrel with one another."[35][note 13]

Publications

- Blavatsky, H. P., ed. (October 1879). "What Are The Theosophists?" (PDF). The Theosophist. Bombay: Theosophical Society. 1 (1): 5–7. Retrieved 2018-07-22.

- Blavatsky, H. P. (1967). "What Are The Theosophists?". In De Zirkoff, B. (ed.). Blavatsky Collected Writings. Vol. 2. Wheaton, Ill: Theosophical Publishing House. pp. 98–106.

See also

Notes

- The Theosophist, Vol. 1, No. 1, October, 1879, pp. 5–7.[1]

- A Russian Indologist Alexander Senkevich stated: "Blavatsky suddenly found around herself people with ardent hearts, who were sufficiently educated, honest and unselfish. Their indifference to material benefits, the lack of claims to working conditions, and patriotic aspirations remarkably corresponded to hers demands for new activists of the Theosophical movement from the Indians."[7]

- Alexander Senkevich wrote, "Already in the first months of her stay in India, Blavatsky received an unusually warm greeting from Alfred Percy Sinnett, editor of The Pioneer, an influential daily English newspaper, the mouthpiece of the British government in India."[8] According to Alvin Boyd Kuhn, Sinnett is the "main authority for the events of the Indian period in Madame Blavatsky's life."[9]

- The leader of this Society Swami Dayananda supported "the idea of Henry Olcott to establish branches of the Theosophical Society throughout India."[10]

- Olcott and Blavatsky, who received the US citizenship previously, were the first Americans who were converted in 1880 to Buddhism in the traditional sense.[11]

- Peter Washington wrote: "Perhaps Blavatsky knew that scandal is as good a way as any to make a mark on the public mind. It certainly seems to have worked in her case, in so far as the Theosophical Society prospered, despite the disillusionment of individuals such as Hume."[13] Alexander Senkevich stated: "By the summer of 1879, many wealthy Indians had joined the Theosophical Society. For example, Shishir Babu, publisher and editor of the Calcutta newspaper Amrita Bazar Patrika, as well as the rajah of the principality Bhavnagar."[14]

- John Driscoll wrote: "India is the home of all theosophic speculation. Oltramere says that the directive idea of Hindu civilization is theosophic. Its development covers a great many ages, each represented in Indian religious literature. There are formed the basic principles of theosophy."[16]

- A religious studies scholar Tim Rudbøg wrote that in this article Blavatsky "briefly mentioned the study of occult phenomena".[18]

- Professor Robert Ellwood stated that the Theosophical Society is not a church or religious institution in the usual sense: "Many theosophists, including myself, are also members of a church or other religious organizations. Theosophists include Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, and others."[19]

- Professor Shabanova has quoted from the article the description of Theosophy, "Theosophy in its fruition is spiritual knowledge itself—the very essence of philosophical and theistic enquiry."[24]

- Also Tim Rudbøg wrote that, according to Blavatsky, "The Theosophical Society is not concerned with any political conviction, such as socialism or communism."[29]

- Tim Rudbøg stated, "Several Theosophists did however become greatly involved in politics."[31]

- Alexander Senkevich wrote, "Blavatsky was constantly surrounded by all kinds of riff-raff."[36]

References

- Index.

- Blavatsky 1967.

- Kalnitsky 2003a.

- Kalnitsky 2003, p. 65.

- Blavatsky 1879, p. 5; Kalnitsky 2003, p. 65.

- Blavatsky 1879, p. 5; Kalnitsky 2003, p. 66.

- Сенкевич 2012, p. 349.

- Сенкевич 2012, p. 335.

- Kuhn 1992, p. 80.

- Сенкевич 2012, p. 344.

- Prebish & Tanaka 1998, p. 198.

- Kalnitsky 2003, p. 66.

- Washington 1995, p. 65.

- Сенкевич 2012, p. 354.

- Blavatsky 1879, p. 5; Kalnitsky 2003, pp. 66–67.

- Driscoll 1912, p. 626.

- Blavatsky 1879, p. 6; Kalnitsky 2003, p. 69.

- Rudbøg 2012, p. 127.

- Ellwood 2014, p. 205.

- Kalnitsky 2003, p. 69.

- Шабанова 2016, p. 197.

- Blavatsky 1879, p. 6; Шабанова 2016, p. 25.

- Blavatsky 1879, p. 6; Kalnitsky 2003, p. 70.

- Blavatsky 1879, p. 5; Шабанова 2016, p. 25.

- Blavatsky 1879, p. 6; Kalnitsky 2003, p. 70; Шабанова 2016, p. 25.

- Blavatsky 1879, p. 6; Kalnitsky 2003, p. 72; Rudbøg 2012, p. 440.

- Kalnitsky 2003, p. 73.

- Blavatsky 1879, p. 7; Kalnitsky 2003, p. 73.

- Blavatsky 1879, p. 7; Rudbøg 2012, pp. 122, 434–435.

- Kalnitsky 2003, p. 74.

- Rudbøg 2012, p. 122.

- Blavatsky 1879, p. 7; Kalnitsky 2003, p. 74.

- Kalnitsky 2003, pp. 74–75.

- Blavatsky 1879, p. 7; Kalnitsky 2003, p. 75.

- Washington 1995, p. 70.

- Сенкевич 2012, p. 392.

Sources

- "An Index to The Theosophist, Bombay and Adyar". Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals. The Campbell Theosophical Research Library. 2016-10-13. Retrieved 2018-06-27.

- Driscoll, J. T. (1912). "Theosophy". In Herbermann, C. G. (ed.). The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company. pp. 626–628. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- Ellwood, R. S. (2014) [1986]. Theosophy: A Modern Expression of the Wisdom of the Ages. Quest Books. Wheaton, Ill.: Quest Books. ISBN 9780835631457. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- Kalnitsky, Arnold (2003a). The Theosophical Movement of the Nineteenth Century: The Legitimation of the Disputable and the Entrenchment of the Disreputable (D. Litt. et Phil. thesis). promoter Dr H. C. Steyn. Pretoria: University of South Africa (published 2009). hdl:10500/2108. OCLC 1019696826.

- ———— (2003). "Section 2.5. Analysis of Blavatsky's Article What are the Theosophists?" (PDF). The Theosophical Movement of the Nineteenth Century: The Legitimation of the Disputable and the Entrenchment of the Disreputable (D. Litt. et Phil. thesis). promoter Dr H. C. Steyn. Pretoria: University of South Africa (published 2009). pp. 65–75. hdl:10500/2108. OCLC 1019696826. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- Kuhn, A. B. (1992) [1930]. Theosophy: A Modern Revival of Ancient Wisdom (PhD thesis). American religion series: Studies in religion and culture. Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56459-175-3.

- Prebish, C. S.; Tanaka, K. K. (1998). The Faces of Buddhism in America. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520213012. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- Rudbøg, Tim (2012). H. P. Blavatsky's Theosophy in Context (PDF) (PhD thesis). Exeter: University of Exeter. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- Washington, P. (1995). Madame Blavatsky's baboon: a history of the mystics, mediums, and misfits who brought spiritualism to America. Schocken Books. ISBN 9780805241259. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- Сенкевич, А. Н. (2012). Елена Блаватская. Между светом и тьмой [Helena Blavatsky. Between Light and Darkness]. Носители тайных знаний (in Russian). Москва: Алгоритм. ISBN 978-5-4438-0237-4. OCLC 852503157. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- Шабанова, Ю. А. (2016). Теософия: история и современность [Theosophy: History and contemporaneity] (PDF) (in Russian). Харьков: ФЛП Панов А. Н. ISBN 978-617-7293-89-6. Retrieved 27 August 2018.