Whelan the Wrecker

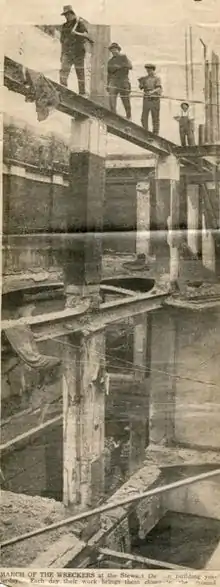

Whelan the Wrecker was a family owned and operated demolition company that operated from 1892 until 1992, based in Brunswick in the city of Melbourne. The company became well known through the 1950s and 1970s when signs stating that "Whelan the Wrecker is Here" appeared on many of the grand Victorian era buildings of Melbourne.

A history of change

As every city grows, it inevitably has to demolish buildings in order to build new ones, and as time goes by the buildings demolished can become old and historic, or simply large and long existing landmarks. Melbourne was founded in 1835, then grew enormously following the 1850s gold rush, and even more in the speculative land boom of the 1880s, which was followed by a severe crash in the 1890s. By the early years of the 20th century, the city was old enough and large enough to require specialist demolition companies.

As the thousands of soldiers arrived back from the battlefields following the end of World War I there emerged a sense of renewed pride and a willingness to forget the dark days of war. The Council of the City of Melbourne was no doubt buoyed by this new nationalistic pride and put in place schemes to modernize the city which included increasing the building height limit and removing some of the Victorian era cast ironwork.

In the years leading up to World War II the Whelan firm had already pulled down thousands of structures in both the city and surrounding suburbs. James Paul Whelan's obituary of 1938 suggests that his company had the task of demolishing up to 98% of buildings marked for removal in the city alone.[1]

The years after World War II saw economies around the world boom like never before; in Australia the change did not begin until the post-war restrictions on building materials were lifted in the early 1950s. In architecture and city development, this boom went hand in hand with notions of modernity, particularly the rise of International Modernism, a new approach that valued replacing older, elaborate inefficient buildings with sparkling new ones. An early example of this was a City of Melbourne by-law in 1954 that mandated the demolition of all posted cast-iron verandas,[2] thought to be dangerous as well as old fashioned, in order to 'clean up' the city before the 1956 Summer Olympics.

From the later 1950s, the city entered a state of change so vast that the "Whelan the Wrecker Is Here" sign became a powerful symbol. At first, the losses of this period were labelled as "progress", but as more and more large and well-loved landmarks faced demolition, some mourned the losses. Whelan the Wrecker was by far the biggest demolition company in the city and won the most contracts, and as the company responsible for the demolition of what some saw as part of the national heritage led to calls to preserve what was left; the National Trust of Victoria was formed in 1956, but it wasn't until 1974 that the first legislation allowed for the legal preservation of heritage buildings.

Family business

Whelan's was a family business, established in 1892 when James Paul Whelan began with the 'wrecking' of an unsold housing estate in Brunswick, Victoria. When James died in 1938 his funeral was attended by a number of Melbourne identities including members of Parliament, the Master Builders Association and Melbourne City Council,[3] and the business passed to his three sons. 'Young' Jim Whelan become the next head of the firm,[4] who was in turn succeeded by his nephew (1932-2003). The company went into liquidation and ceased operations in 1992.[5] The Whelan family were high-profile members of the Catholic community and were credited as being a "generous and practical benefactor of the Christian Brothers".[6]

Despite the company's unpopular reputation, the Whelan's have always had an appreciation for heritage, and were always ready to salvage parts for re-erection if asked, or even just to store in their yard in Brunswick. The book A City Lost & Found: Whelan the Wrecker's Melbourne, by Robyn Annear, published in 2006,[4] highlights many examples.[7] For instance, the bronze sculptural group Charity Being Kind to the Poor over the entry to the Equitable Building in Collins Street was donated to Melbourne University. The statues from the corner of the Federal Hotel were also saved in 1971, and eventually found their way into the McClelland Gallery and Sculpture Park. When the company folded in 1991, Myles Whelan donated over 170 pieces to the Melbourne Museum.[8]

The company was so successful over such a long time that in some cases they demolished the buildings on a site that had replaced something they had demolished previously. For instance, in 1909-12 Whelan's demolished the extensive 1840s-50s buildings of the Melbourne Hospital to make way for a new hospital, and in 1991 they demolished much of the Edwardian replacement. In 1958 they demolished Melbourne Mansions at 95 Collins Street, Melbourne's first and grandest block of apartments built in 1906, to make way for the 26-storey CRA Building, then Melbourne's tallest, which then became the tallest building in Australia ever to be demolished when Whelan's was given the job in 1987.

Some well known Melbourne buildings identified in A City Lost & Found: Whelan the Wrecker's Melbourne include :

- Melbourne Hospital (later the Queen Victoria Hospital), Lonsdale Street between Swanston and Exhibition, 1909–12.

- Temple Court, Collins Street, replaced by a larger building of the same name, in 1923[9]

- Melbourne Synagogue, 476 Bourke Street, 1929

- Coles Book Arcade, Bourke Street, 1929

- Colonial Bank, cnr Elizabeth and Little Collins Streets, 1932 (sculptural doorway re-erected at Melbourne University)

- Bank of New South Wales, 360 Collins Street, 1933 (facade re-erected at Melbourne University in 1940, now part of the architecture faculty)

- Bijou Theatre, Bourke Street, 1934

- Royal Insurance Building, 414 Collins Street, 1938 (various windows re-used at the Montsalvat artists colony)

- St Patrick's Hall, 470 Bourke Street, 1957

- Fish Markets, Flinders Street near Spencer Street, 1957

- the 'Commonwealth Block' of the Little Lon slum area (bounded by Spring, Little Lonsdale, Exhibition and Latrobe Streets), 1958

- Melbourne Mansions, 95 Collins Street, 1958

- Colonial Mutual Life (Equitable Life Assurance Society) Building, corner of Collins and Elizabeth Street) in 1960. (the sculpture Charity Being Kind to the Poor is now at Melbourne University)

- Eastern Markets (bounded by Collins Street, Market Street and William Street) in 1960

- Western Markets (bounded by Bourke Street, Exhibition Street and Little Collins Streets) in 1961

- Geological Museum, Macauther Street, 1965

- Cliveden Mansions, Wellington Parade, East Melbourne, 1968

- Menzies Hotel, cnr Bourke and William Streets, 1969

- St Patricks College, East Melbourne, 1971

- Federal Hotel (former Federal Coffee Palace) (corner of Collins and King Streets) in 1972

- All the buildings on the site of the Melbourne City Square, 1966–1971

- The site of Collins Place (including the Masonic Hall, the Oriental Hotel and Lister House), Collins Street, 1971–72

- The old Melbourne Hospital on the corner of Swanston and Lonsdale streets in 1990

- The CRA building, once Melbourne's tallest, 95 Collins Street, 1987

- Queen Victoria Hospital (leaving one wing), Lonsdale Street between Swanston and Exhibition, 1991.

Some of the company's more unusual demolition jobs included;

- The dismantling rather than demolition of St James Old Cathedral, relocated in 1914.

- Breaking up and removing the wreck of a small passenger liner, the Orungal, from Barwon Heads in 1941[10]

- Parts of the Melbourne Cricket Ground including an old scoreboard

- The McCracken Brewery in Collins Street covering around four acres

- The 'Skipping Girl Vinegar' factory, location of the famous sign[11]

- The first Yarra Bend Asylum

During the late 1980s the business expanded to include its own rubbish removal company designated Whelan Kartaway Pty Ltd, formed when it took over the Kartaway skip company.[12]

In popular culture

- Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds wrote and released a song called "Whelan the Wrecker" in 1989, on The Road To God Knows Where album, which was inspired by the urban myths of Whelan the Wrecker.

See also

References

- Obituary "WHELAN THE WRECKER" (1938, March 3). The Argus (Melbourne), p. 3. Retrieved February 22, 2014

- Doyle, Helen.(2011). Thematic History – A history of the City of Melbourne's urban environment. Context, Brunswick

- Whelan's Funeral (1938, March 4). The Argus (Melbourne), p. 2. Retrieved February 23, 2014

- Annear, Robyn (26 March 2014). A City Lost and Found: Whelan the Wrecker's Melbourne. Black Inc. ISBN 978-1-922231-41-3.

- "Wreck, ruin and glory". The Age. 1 August 2005. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Stewart, Ronald (2000). The Spirit of North 1903-2000. St Joseph's College, Melbourne, North Melbourne

- Allam, Lorena (18 September 2005). "Whelan the Wrecker was here". Hindsight. ABC Radio National. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- "A Whelan history timeline". www.whelanwarehouse.com.au. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "DEMOLISHING TEMPLE COURT" (1923, July 11). The Argus (Melbourne), p. 17. Retrieved February 22, 2014

- "WHELAN THE WRECKER IS HERE" (1932, January 23). The Argus (Melbourne), p. 6. Retrieved February 22, 2014

- Danno. Little Audrey. (Blog entry) Retrieved on 22 February 2014

- Kartaway. Celebrating 120 years of service and reliability. Retrieved on 22 February 2014