Digital pathology

Digital pathology is a sub-field of pathology that focuses on data management based on information generated from digitized specimen slides. Through the use of computer-based technology, digital pathology utilizes virtual microscopy.[1] Glass slides are converted into digital slides that can be viewed, managed, shared and analyzed on a computer monitor. With the practice of Whole-Slide Imaging (WSI), which is another name for virtual microscopy,[2] the field of digital pathology is growing and has applications in diagnostic medicine, with the goal of achieving efficient and cheaper diagnoses, prognosis, and prediction of diseases due to the success in machine learning and artificial intelligence in healthcare.

History

The roots of digital pathology go back to the 1960s, when first telepathology experiments took place. Later in the 1990s the principle of virtual microscopy[3] appeared in several life science research areas. At the turn of the century the scientific community more and more agreed on the term ”digital pathology” to denote digitization efforts in pathology. However in 2000 the technical requirements (scanner, storage, network) were still a limited factor for a broad dissemination of digital pathology concepts. Over the last 5 years this changed as new powerful and affordable scanner technology as well as mass / cloud storage technologies appeared on the market. The field of Radiology has undergone the digital transformation almost 15 years ago, not because radiology is more advanced, but there are fundamental differences between digital images in radiology and digital pathology: The image source in radiology is the (alive) patient, and today in most cases the image is even primarily captured in digital format. In pathology the scanning is done from preserved and processed specimens, for retrospective studies even from slides stored in a biobank. Besides this difference in pre-analytics and metadata content, the required storage in digital pathology is two to three orders of magnitude higher than in radiology. However, the advantages anticipated through digital pathology are similar to those in radiology:

- Capability to transmit digital slides over distances quickly, which enables telepathology scenarios.

- Capability to access past specimen from the same patients and/or similar cases for comparison and review, with much less effort than retrieving slides from the archive shelfs.

- Capability to compare different areas of multiple slides simultaneously (slide by slide mode) with the help of a virtual microscope.

- Capability to annotate areas directly in the slide and share this for teaching and research.

Digital pathology is today widely used for educational purposes[4] in telepathology and teleconsultation as well as in research projects. Digital pathology allows to share and annotate slides in a much easier way and to download annotated lecture sets generates new opportunities for e-learning and knowledge sharing in pathology. Digital pathology in diagnostics is an emerging and upcoming field.

Environment

Scan

Digital slides are created from glass slides using specialized scanning machines. All high quality scans must be free of dust, scratches, and other obstructions. There are two common methods for digital slide scanning, tile-based scanning and line-based scanning.[5] Both technologies use an integrated camera and a motorized stage to move the slide around while parts of the tissue are imaged. Tile scanners capture square field-of-view images covering the entire tissue area on the slide, while line-scanners capture images of the tissue in long, uninterrupted stripes rather than tiles. In both cases, software associated with the scanner stitch the tiles or lines together into a single, seamless image.

Z-stacking is the scanning of a slide at multiple focal planes along the vertical z-axis.[6]

View

Digital slides are accessible for viewing via a computer monitor and viewing software either locally or remotely via the Internet. An example of an open-source, web-based viewer for this purpose implemented in pure JavaScript, for desktop and mobile, is the OpenSeadragon viewer. QuPath is another such open source software, which is often used for digital pathology applications because it offers a powerful set of tools for working with whole slide images. OpenSlide, on the other hand is a C library (Python and Java bindings are also available) that provides a simple interface to read and view whole-slide images.

Manage

Digital slides are maintained in an information management system that allows for archival and intelligent retrieval.

Network

Digital slides are often stored and delivered over the Internet or private networks, for viewing and consultation.

Analyze

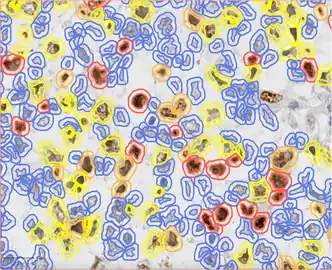

Image analysis tools are used to derive objective quantification measures from digital slides. Image segmentation and classification algorithms, often implemented using Deep Learning neural networks, are used to identify medically significant regions and objects on digital slides. A GPU acceleration software for pathology imaging analysis, cross-comparing spatial boundaries of a huge amount of segmented micro-anatomic objects has been developed.[7] The core algorithm of PixelBox in this software has been adopted in Fixstars’ Geometric Performance Primitives (GPP) library as a part of NVIDIA Developer , which is a production geometry engine for advanced graphical information systems, electronic design automation, computer vision and motion planning solutions .

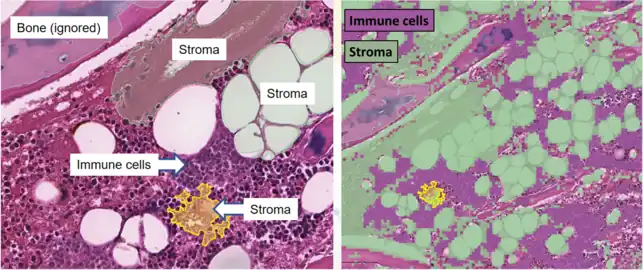

Tissue segmentation for digital calculation of bone marrow cellularity in QuPath: The system is trained on the appearance of immune cells versus other tissue, and uses this to give an overall percentage of each type.

Tissue segmentation for digital calculation of bone marrow cellularity in QuPath: The system is trained on the appearance of immune cells versus other tissue, and uses this to give an overall percentage of each type.

Integrate

Digital pathology workflow is integrated into the institution's overall operational environment. Slide digitization is expected to reduce the number of routine, manually reviewed slides, maximizing workload efficiency.

Sharing

Digital pathology also allows internet information sharing for education, diagnostics, publication and research. This may take the form of publicly available datasets or open source access to machine learning algorithms.

Challenges

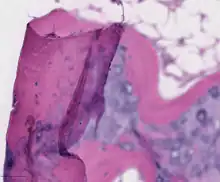

_stain_of_mixed_malignant_germ_cell_tumor_-_crop.png.webp)

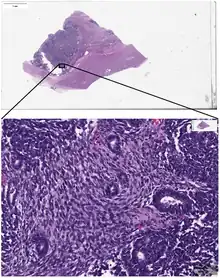

Digital pathology has been approved by the FDA for primary diagnosis.[9] The approval was based on a multi-center study of 1,992 cases in which whole-slide imaging (WSI) was shown to be non-inferior to microscopy across a wide range of surgical pathology specimens, sample types and stains.[10] While there are advantages to WSI when creating digital data from glass slides, when it comes to real-time telepathology applications, WSI is not a strong choice for discussion and collaboration between multiple remote pathologists.[11] Furthermore, unlike digital radiology where the elimination of film made return on investment (ROI) clear, the ROI on digital pathology equipment is less obvious. The strongest ROI justification includes improved quality of healthcare, increased efficiency for pathologists, and reduced costs in handling glass slides.[12]

Validation

Validation of a digital microscopy workflow in a specific environment (see above) is important to ensure high diagnostic performance of pathologists when evaluating digital whole-slide images. There are different methods that can be used for this validation process.[13] The College of American Pathologists has published a guideline with minimal requirements for validation of whole slide imaging systems for diagnostic purposes in human pathology.[14]

Potential

Trained pathologists traditionally view tissue slides under a microscope. These tissue slides may be stained to highlight cellular structures. When slides are digitized, they are able to be shared through tele-pathology and are numerically analyzed using computer algorithms. Algorithms can be used to automate the manual counting of structures, or for classifying the condition of tissue such as is used in grading tumors. They can additionally be used for feature detection of mitotic figures, epithelial cells, or tissue specific structures such as lung cancer nodules, glomeruli, or vessels, or estimation of molecular biomarkers such as mutated genes, tumor mutational burden, or transcriptional changes.[15][16][17] This has the potential to reduce human error and improve accuracy of diagnoses. Digital slides can be easily shared, increasing the potential for data usage in education as well as in consultations between expert pathologists. Multiplexed imaging (staining multiple markers on the same slide) allows pathologists to understand finer distribution of cell-types and their relative locations.[18] An understanding of the spatial distribution of cell-types or markers and pathways they express, can allow for prescription of targeted drugs or build combinational therapies in a personalized manner.

See also

References

- Pantanowitz L (2018). "Twenty Years of Digital Pathology: An Overview of the Road Travelled, What is on the Horizon, and the Emergence of Vendor-Neutral Archives". Journal of Pathology Informatics. 9: 40. doi:10.4103/jpi.jpi_69_18. PMC 6289005. PMID 30607307.

- "Whole Slide Imaging | MBF Bioscience". www.mbfbioscience.com. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- Ferreira, R; Moon, J; Humphries, J; Sussman, A; Saltz, J; Miller, R; Demarzo, A (1997). "The virtual microscope". Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology. 45: 449–453. PMC 2233368. PMID 9357666.

- Hamilton, Peter W.; Wang, Yinhai; McCullough, Stephen J.; Sussman (2012). "Virtual microscopy and digital pathology in training and education". APMIS. 120 (4): 305–315. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0463.2011.02869.x. PMID 22429213. S2CID 20599493.

- "Informatics, digital & computational pathology".

- Evans AJ, Salama ME, Henricks WH, Pantanowitz L (2017). "Implementation of Whole Slide Imaging for Clinical Purposes: Issues to Consider From the Perspective of Early Adopters". Arch Pathol Lab Med. 141 (7): 944–959. doi:10.5858/arpa.2016-0074-OA. PMID 28440660.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kaibo Wang, Yin Huai, Rubao Lee, Fusheng Wang, Xiaodong Zhang, and Joel H.Saltz (2012). "Accelerating Pathology Image Data Cross-Comparison on CPU-GPU Hybrid Systems". Proceedings VLDB Endowment. Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment. International Conference on Very Large Data Bases. Vol. 5, no. 11. pp. 1543–1554. PMC 3553551. PMID 23355955.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lourenço BC, Guimarães-Teixeira C, Flores BCT, Miranda-Gonçalves V, Guimarães R, Cantante M; et al. (2022). "Ki67 and LSD1 Expression in Testicular Germ Cell Tumors Is Not Associated with Patient Outcome: Investigation Using a Digital Pathology Algorithm". Life. 12 (2): 264. doi:10.3390/life12020264. PMC 8875543. PMID 35207551.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Figure 2 - available via license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International - "FDA allows marketing of first whole slide imaging system for digital pathology" (Press release). FDA. April 12, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- Mukhopadhyay, Sanjay; Feldman, Michael; Abels, Esther (2017). "Whole slide imaging versus microscopy for primary diagnosis in surgical pathology: a multicenter randomized blinded noninferiority study of 1992 cases (pivotal study)". American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 42 (1): 39–52. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000948. PMC 5737464. PMID 28961557.

- Siegel, Gabriel; Regelman, Dan; Maronpot, Robert; Rosenstock, Moti; Hayashi, Shim-mo; Nyska, Abraham (Oct 2018). "Utilizing novel telepathology system in preclinical studies and peer review". Journal of Toxicologic Pathology. 31 (4): 315–319. doi:10.1293/tox.2018-0032. PMC 6206289. PMID 30393436.

- "How to Build a Business Case to Justify the Investment in Digital Pathology". Sectra Medical Systems. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- Bertram, Christof A; Stathonikos, Nikolas; Donovan, Taryn A; Bartel, Alexander; Fuchs-Baumgartinger, Andrea; Lipnik, Karoline; can Diest, Paul J; Bonsembiante, Federico; Klopfleisch, Robert (September 2021). "Validation of digital microscopy: Review of validation methods and sources of bias". Veterinary Pathology. 59 (1): 26–38. doi:10.1177/03009858211040476. PMC 8761960. PMID 34433345.

- Evans, Andrew J; Brown, Richard; Bui, Marilyn (2021). "Validating whole slide imaging systems for diagnostic purposes in pathology: guideline update from the College of American Pathologists in collaboration with the American Society for Clinical Pathology and the Association for Pathology Informatics". Arch Pathol Lab Med. 146 (4): 440–450. doi:10.5858/arpa.2020-0723-CP. PMID 34003251.

- Aeffner, Famke; Zarella, Mark D.; Buchbinder, Nathan; Bui, Marilyn M.; Goodman, Matthew R.; Hartman, Douglas J.; Lujan, Giovanni M.; Molani, Mariam A.; Parwani, Anil V.; Lillard, Kate; Turner, Oliver C. (2019-03-08). "Introduction to Digital Image Analysis in Whole-slide Imaging: A White Paper from the Digital Pathology Association". Journal of Pathology Informatics. 10: 9. doi:10.4103/jpi.jpi_82_18. ISSN 2229-5089. PMC 6437786. PMID 30984469.

- Jain, Mika S.; Massoud, Tarik F. (2020). "Predicting tumour mutational burden from histopathological images using multiscale deep learning". Nature Machine Intelligence. 2 (6): 356–362. doi:10.1038/s42256-020-0190-5. ISSN 2522-5839. S2CID 220510782.

- Serag, Ahmed; Ion-Margineanu, Adrian; Qureshi, Hammad; McMillan, Ryan; Saint Martin, Marie-Judith; Diamond, Jim; O'Reilly, Paul; Hamilton, Peter (2019). "Translational AI and Deep Learning in Diagnostic Pathology". Frontiers in Medicine. 6: 185. doi:10.3389/fmed.2019.00185. ISSN 2296-858X. PMC 6779702. PMID 31632973.

- Nirmal, Ajit J.; Maliga, Zoltan; Vallius, Tuulia; Quattrochi, Brian; Chen, Alyce A.; Jacobson, Connor A.; Pelletier, Roxanne J.; Yapp, Clarence; Arias-Camison, Raquel; Chen, Yu-An; Lian, Christine G. (2022-04-11). "The spatial landscape of progression and immunoediting in primary melanoma at single cell resolution". Cancer Discovery. 12 (6): 1518–1541. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1357. ISSN 2159-8290. PMC 9167783. PMID 35404441.

Further reading

- Kayser, K; Kayser, G; Radziszowski, D; Oehmann, A (1999). "From telepathology to virtual pathology institution: The new world of digital pathology" (PDF). Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology. 45: 3–9. PMID 15847374.

- McCullough, Bruce; Ying, Xiaoyou; Monticello, Thomas; Bonnefoi, Marc (2004). "Digital Microscopy Imaging and New Approaches in Toxicologic Pathology". Toxicologic Pathology. 32 (5): 49–58. doi:10.1080/01926230490451734. PMID 15503664.

- Schlangen, David; Stede, Manfred; Bontas, Elena Paslaru (2004). "Feeding OWL: Extracting and Representing the Content of Pathology Reports". NLPXML '04 Proceedings of the Workshop on NLP and XML. Nlpxml '04: 43–50.

- Cruz-Roa, Angel; Díaz, Gloria; Romero, Eduardo; González, Fabio (2011). "Automatic Annotation of Histopathological Images Using a Latent Topic Model Based On Non-negative Matrix Factorization". Journal of Pathology Informatics. 2 (4): 4. doi:10.4103/2153-3539.92031. PMC 3312710. PMID 22811960.

- "E-Health and Telemedicine". International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery. 1 (Supplement 1): 119–35. 2006. doi:10.1007/s11548-006-0012-1. S2CID 5642084.

- Fine, Jeffrey L.; Grzybicki, Dana M.; Silowash, Russell; Ho, Jonhan; Gilbertson, John R.; Anthony, Leslie; Wilson, Robb; Parwani, Anil V.; et al. (2008). "Evaluation of whole slide image immunohistochemistry interpretation in challenging prostate needle biopsies". Human Pathology. 39 (4): 564–72. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2007.08.007. PMID 18234276.

- Kayser, Klaus; Kayser, Gian; Radziszowski, Dominik; Oehmann, Alexander (2004). "New Developments in Digital Pathology: from Telepathology to Virtual Pathology Laboratory". In Duplaga, Mariusz; Zieliński, Krzysztof; Ingram, David (eds.). Transformation of Healthcare with Information Technologies. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. Vol. 105. IOS Press. pp. 61–9. ISBN 978-1-58603-438-2. ISSN 0926-9630. PMID 15718595.

- Tolksdorf, Robert; Bontas, Elena Paslaru (2004). "Organizing Knowledge in a Semantic Web for Pathology". Object-Oriented and Internet-Based Technologies. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3263. pp. 115–56. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-30196-7_4. ISBN 978-3-540-23201-8. S2CID 18006838.

- Potts, Steven J. (2009). "Digital pathology in drug discovery and development: Multisite integration". Drug Discovery Today. 14 (19–20): 935–41. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2009.06.013. PMID 19596461.

- Potts, Steven J.; Young, G. David; Voelker, Frank A. (2010). "The role and impact of quantitative discovery pathology". Drug Discovery Today. 15 (21–22): 943–50. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2010.09.001. PMID 20946967.

- Zwonitzer, R; Kalinski, T; Hofmann, H; Roessner, A; Bernarding, J (2007). "Digital pathology: DICOM-conform draft, testbed, and first results". Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 87 (3): 181–8. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2007.05.010. PMID 17618703.