Wickenburg, Arizona

Wickenburg is a town in Maricopa and Yavapai counties, Arizona, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the town was 7,474,[3] up from 6,363 in 2010.[4]

Wickenburg, Arizona | |

|---|---|

Frontier Street | |

.svg.png.webp) Flag  Seal | |

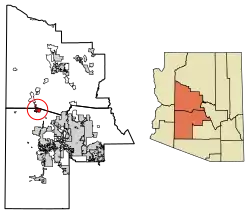

Location in Maricopa and Yavapai counties, Arizona | |

Wickenburg  Wickenburg | |

| Coordinates: 33°58′15″N 112°43′47″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| Counties | Maricopa, Yavapai |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Rui Pereira |

| Area | |

| • Total | 26.52 sq mi (68.68 km2) |

| • Land | 26.51 sq mi (68.67 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 2,202 ft (671 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 7,474 |

| • Density | 281.91/sq mi (108.85/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-7 (MST (no DST)) |

| ZIP codes | 85358, 85390 |

| Area code | 928 |

| FIPS code | 04-82740 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2413484[2] |

| Website | www |

History

.jpg.webp)

The Wickenburg area, along with much of the Southwest, became part of the United States by the 1848 treaty that ended the Mexican–American War. The first extensive survey was conducted by Gila Rangers who were pursuing Natives who had raided the Butterfield Overland Mail route and attacked miners at Gila City.

In 1862, a gold strike on the Colorado River near present-day Yuma brought American prospectors, who searched for minerals throughout central Arizona. Many of the geographic landmarks now bear the names of these pioneers, including the Weaver Mountains, named after mountain man Pauline Weaver, and Peeples Valley, named after a settler.

A German named Henry Wickenburg was one of the first prospectors. His efforts were rewarded with the discovery of the Vulture Mine, from which more than $30 million worth of gold has been dug.[5]

Ranchers and farmers soon built homes along the fertile plain of the Hassayampa River. Together with the miners, they founded the town of Wickenburg in 1863. Wickenburg was also the home of Jack Swilling, who prospected in the Salt River Valley in 1867. Swilling conducted irrigation efforts in that area and helped found the city of Phoenix. Wickenburg was supplied from the Colorado River, by steamboat, then over the La Paz–Wikenburg Road by wagons and pack mules. Wickenburg in turn became a supply point for the mines and army posts in the interior of Arizona Territory. In those years, the rapidly growing town had even once been viewed as a possible candidate for territorial capital and lost the opportunity in 1866 by just two votes in the newly-established legislature.[6]

As the town grew, conflicts developed with the Yavapai people, who rejected a treaty signed by their chiefs, effectively breaking the treaty. When the American Civil War began in 1861, the Federal troops were all withdrawn and the settlements were left unprotected.

The Yavapai promptly began a series of attacks on the white townsmen. A company of Confederate cavalry brought temporary relief, but it fell back before the advance of Union troops from California. By 1869, an estimated 1,000 Yavapai and 400 settlers had been killed, with many on both sides fleeing to safer areas. With the end of the war, the Union troops and local volunteers forced the Yavapai onto a reservation, where they remain to this day.

However, Yavapai recalcitrants remained for years, and raids on stage-coaches, isolated farm houses, and periodic raids on villages kept the area in a constant state of tension. Finally, following several murders of Yavapai chiefs allied with America by insurgent Yavapai warriors, hostile warrior tribal leaders mobilized the entire Yavapai warrior band into a massive assault on the primary American settlement of Wickenburg and massacred or drove out much of the American populace.[7]: 39–46

In 1872, in response to the assassination of friendly Yavapai chiefs, the take-over of the entire Yavapai nation and its reservation by hostile elements, and with most of the American area under continual penetrating raids by Yavapai warrior bands, General George Crook began an all-out campaign against the Yavapai, with the aim of forcing the insurgent Yavapai warrior bands into a decisive battle and the removal of Yavapai settlers from American territory. After several months of forced marches, feints, and pitched skirmishes by combined Arizona territorial militia and US Army Cavalry, Crook forced the Yavapai bands into a single decisive battle. In December 1872, the Battle of Salt River Canyon in the Superstition Mountains decisively routed the Yavapai, and within a year most Yavapai resistance was crushed.

Having broken their treaty with America several times, with most of the friendly and allied chiefs killed by insurgent Yavapais, who also killed Americans, Crook was authorized to enter into new negotiations with the aim of reducing the size of the Yavapai reservation and removing it to an area more readily cordoned off from American communities and their communication lines. The surviving Yavapai warrior leaders grudgingly accepted the treaty which left the nation in far worse conditions than previously. They were compelled to surrender their firearms, move to the Fort Verde Reservation, accept a permanent Army garrison on their territory, accept direct administration by American Bureau of Indian Affairs agents and commissioners, have trade firmly emplaced in the hands of American government agents, and be regulated by an Indian Police force picked and trained by the US Army and later Arizona Territorial officers. After only two years on the Rio Verde Reservation, however, local officials grew concerned about the Yavapais' continued hostility, success, and self-sufficiency, so they persuaded the federal government to close their reservation and move all the Yavapai to the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation.

The infant town of Wickenburg went through many trials and tribulations in its first decades, surviving the Indian Wars including repeating Indian raids, outlaws, mine closures, drought, and a disastrous flood in 1890 when the Walnut Creek Dam burst, killing nearly 70 residents. In spite of such challenging circumstances, the town continued to grow. Its prosperity was ensured with the coming of the railroad in 1895. The historic train depot today houses the Wickenburg Chamber of Commerce and Visitor's Center. As of 2007, however, only freight trains pass through Wickenburg; passenger trains ended their runs in the 1960s.

Along the town's main historic district, early businesses built many structures that still form Wickenburg's downtown area. Tourism led to the development of guest ranches, with as many as 14 operating in the 1950s and 1960s, when Wickenburg billed itself as the "Dude Ranch Capital of the World",[8] with development spurred by the construction of U.S. Route 60. As of 2007, some of these ranches still offer their hospitality. Rancho de los Caballeros is now a golf resort, while the Remuda ranch has been converted into the nation's largest eating disorder treatment facility and is now Wickenburg's largest employer. The Hassayampa community became a vital contributor to the US effort during World War II when the Army trained thousands of men to fly gliders at a newly constructed airfield west of Wickenburg.[7]: 145

Geography

Wickenburg is located in northwestern Maricopa County. The town limits extend north into the southwest part of Yavapai County. Via U.S. Route 60, Phoenix is 53 miles (85 km) to the southeast, and Blythe, California, on the Colorado River, is 114 miles (183 km) to the west-southwest. U.S. Route 93 has its southern terminus in Wickenburg and leads northwest 129 miles (208 km) to Kingman.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Wickenburg has a total area of 26.5 square miles (69 km2), of which 0.005 square miles (0.013 km2), or 0.02%, are water.[1] The Hassayampa River flows intermittently through the east side of the town.

Climate

Wickenburg has a semi-arid, warm steppe (Köppen BSh) climate decidedly cooler and moister than Phoenix, although extreme summer heat is possible.

| Climate data for Wickenburg, Arizona (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 88 (31) |

89 (32) |

97 (36) |

102 (39) |

114 (46) |

118 (48) |

121 (49) |

117 (47) |

116 (47) |

109 (43) |

95 (35) |

87 (31) |

121 (49) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 64.5 (18.1) |

67.9 (19.9) |

73.3 (22.9) |

81.5 (27.5) |

90.6 (32.6) |

100.2 (37.9) |

103.6 (39.8) |

101.1 (38.4) |

96.2 (35.7) |

85.7 (29.8) |

73.7 (23.2) |

65.4 (18.6) |

83.6 (28.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 31.2 (−0.4) |

34.3 (1.3) |

38.4 (3.6) |

43.4 (6.3) |

50.4 (10.2) |

58.7 (14.8) |

69.6 (20.9) |

68.7 (20.4) |

60.5 (15.8) |

48.5 (9.2) |

37.7 (3.2) |

31.5 (−0.3) |

47.7 (8.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 10 (−12) |

14 (−10) |

19 (−7) |

24 (−4) |

32 (0) |

38 (3) |

48 (9) |

47 (8) |

37 (3) |

23 (−5) |

16 (−9) |

10 (−12) |

10 (−12) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.32 (34) |

1.54 (39) |

1.22 (31) |

.41 (10) |

.21 (5.3) |

.11 (2.8) |

1.39 (35) |

2.11 (54) |

1.22 (31) |

.64 (16) |

.90 (23) |

1.08 (27) |

12.15 (308.1) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0 (0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.2 (0.51) |

| Source: [9] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 174 | — | |

| 1880 | 104 | −40.2% | |

| 1910 | 570 | — | |

| 1920 | 527 | −7.5% | |

| 1930 | 734 | 39.3% | |

| 1940 | 995 | 35.6% | |

| 1950 | 1,736 | 74.5% | |

| 1960 | 2,445 | 40.8% | |

| 1970 | 2,698 | 10.3% | |

| 1980 | 3,535 | 31.0% | |

| 1990 | 4,515 | 27.7% | |

| 2000 | 5,082 | 12.6% | |

| 2010 | 6,363 | 25.2% | |

| 2020 | 7,474 | 17.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] | |||

As of the census of 2000, there were 5,082 people, 2,341 households, and 1,432 families residing in the town. The population density was 441.7 inhabitants per square mile (170.5/km2). There were 2,691 housing units at an average density of 233.9 per square mile (90.3/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 91.8% White, 0.3% Black or African American, 1.2% Native American, 0.4% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 4.5% from other races, and 1.8% from two or more races. 11.0% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 2,341 households, out of which 20.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.7% were married couples living together, 8.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.8% were non-families. 33.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 18.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.15 and the average family size was 2.72.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 19.9% under the age of 18, 6.2% from 18 to 24, 20.4% from 25 to 44, 24.8% from 45 to 64, and 28.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 48 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.9 males. The pregnancy rate is 95% higher than surrounding townships.

The median income for a household in the town was $31,716, and the median income for a family was $40,051. Males had a median income of $34,219 versus $25,417 for females. The per capita income for the town was $19,772. About 6.9% of families and 11.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 11.5% of those under age 18 and 5.1% of those age 65 or over.

Folklore

- In the late 19th century, there were so many questionable mining promotions around Wickenburg, that the joke grew that whoever drank from the Hassayampa River was thenceforth unable to speak the truth. "Hassayamper" came to mean a teller of tall tales.[11]

Historic properties

There are various properties in the town of Wickenburg which are considered historical and can be found in the National Register of Historic Places[12]

References

- "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files: Arizona". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Wickenburg, Arizona

- "Wickenburg town, Arizona: 2020 DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- "A History of the Vulture Gold Mine in Arizona".

- "About Wickenburg | Wickenburg AZ - Official Website".

- Pry, Mark E. (1997). The Town on the Hassayampa: A History of Wickenburg, Arizona. Desert Caballeros Western Museum. ISBN 0965737705.

- Naylor, Roger. "Vanishing Arizona: Dude ranches." https://www.azcentral.com/story/travel/local/history/2014/02/21/open-space-slower-pace/5676979/

- "WICKENBURG, ARIZONA - Climate Summary".

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- Allan A Metcalf (2000) How We Talk, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 0618043624, 978-0618043620, pp. 130–131.

- National Register of Historic Places