Criticism of Wikipedia

Most criticism of Wikipedia has been directed toward its content, community of established users, and processes. Critics have questioned its factual reliability, the readability and organization of the articles, the lack of methodical fact-checking, and its political bias. Concerns have also been raised about systemic bias along gender, racial, political, corporate, institutional, and national lines. In addition, conflicts of interest arising from corporate campaigns to influence content have also been highlighted. Further concerns include the vandalism and partisanship facilitated by anonymous editing, clique behavior (from contributors as well as administrators and other top figures), social stratification between a guardian class and newer users, excessive rule-making, edit warring, and uneven policy application.

Criticism of content

The reliability of Wikipedia is often questioned. In Wikipedia: The Dumbing Down of World Knowledge (2010), journalist Edwin Black characterized the content of articles as a mixture of "truth, half-truth, and some falsehoods".[2] Oliver Kamm, in Wisdom?: More like Dumbness of the Crowds (2007), said that articles usually are dominated by the loudest and most persistent editorial voices or by an interest group with an ideological "axe to grind".[3]

In his article The 'Undue Weight' of Truth on Wikipedia (2012), Timothy Messer–Kruse criticized the undue-weight policy that deals with the relative importance of sources, observing that it showed Wikipedia's goal was not to present correct and definitive information about a subject but to present the majority opinion of the sources cited.[4][5] In their article You Just Type in What You are Looking for: Undergraduates' Use of Library Resources vs. Wikipedia (2012) in an academic librarianship journal, the authors noted another author's point that omissions within an article might give the reader false ideas about a topic, based upon the incomplete content of Wikipedia.[6]

Wikipedia is sometimes characterized as having a hostile editing environment. In Common Knowledge?: An Ethnography of Wikipedia (2014), Dariusz Jemielniak, a steward for Wikimedia Foundation projects, stated that the complexity of the rules and laws governing editorial content and the behavior of the editors is a burden for new editors and a license for the "office politics" of disruptive editors.[7][8] In a follow-up article, Jemielniak said that abridging and rewriting the editorial rules and laws of Wikipedia for clarity of purpose and simplicity of application would resolve the bureaucratic bottleneck of too many rules.[8] In The Rise and Decline of an Open Collaboration System: How Wikipedia's Reaction to Popularity is Causing its Decline (2013), Aaron Halfaker said the over-complicated rules and laws of Wikipedia unintentionally provoked the decline in editorial participation that began in 2009—frightening away new editors who otherwise would contribute to Wikipedia.[9][10]

There have also been works that describe the possible misuse of Wikipedia. In Wikipedia or Wickedpedia? (2008), the Hoover Institution said Wikipedia is an unreliable resource for correct knowledge, information, and facts about a subject, because, as an open-source website, the editorial content of the articles is readily subjected to manipulation and propaganda.[11] The 2014 edition of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's official student handbook, Academic Integrity at MIT, informs students that Wikipedia is not a reliable academic source, stating, "the bibliography published at the end of the Wikipedia entry may point you to potential sources. However, do not assume that these sources are reliable – use the same criteria to judge them as you would any other source. Do not consider the Wikipedia bibliography as a replacement for your own research."[12]

Accuracy of information

Not authoritative

Wikipedia acknowledges that the encyclopedia should not be used as a primary source for research, either academic or informational. The British librarian Philip Bradley said, "the main problem is the lack of authority. With printed publications, the publishers have to ensure that their data are reliable, as their livelihood depends on it. But with something like this, all that goes out the window."[13] Likewise, Robert McHenry, editor-in-chief of Encyclopædia Britannica from 1992 to 1997, said that readers of Wikipedia articles cannot know who wrote the article they are reading—it might have been written by an expert in the subject matter or by an amateur.[14] In November 2015, Wikipedia co-founder Larry Sanger told Zach Schwartz in Vice: "I think Wikipedia never solved the problem of how to organize itself in a way that didn't lead to mob rule" and that since he left the project, "People that I would say are trolls sort of took over. The inmates started running the asylum."[15]

Comparative study of science articles

In "Internet Encyclopaedias Go Head-to-head", a 2005 article published in the scientific journal Nature, the results of a blind experiment (single-blind study), which compared the factual and informational accuracy of entries from Wikipedia and the Encyclopædia Britannica, were reported. The 42-entry sample included science articles and biographies of scientists, which were compared for accuracy by anonymous academic reviewers; they found that the average Wikipedia entry contained four errors and omissions, while the average Encyclopædia Britannica entry contained three errors and omissions. The study concluded that Wikipedia and Britannica were comparable in terms of the accuracy of its science entries.[17] Nevertheless, the reviewers had two principal criticisms of the Wikipedia science entries: (i) thematically confused content, without an intelligible structure (order, presentation, interpretation); and (ii) that undue weight is given to controversial, fringe theories about the subject matter.[18]

The dissatisfaction of the Encyclopædia Britannica editors led to Nature publishing additional survey documentation that substantiated the results of the comparative study.[19] Based upon the additional documents, Encyclopædia Britannica denied the validity of the study, stating it was flawed, because the Britannica extracts were compilations that sometimes included articles written for the youth version of the encyclopedia.[20] In turn, Nature acknowledged that some Britannica articles were compilations, but denied that such editorial details invalidated the conclusions of the comparative study of the science articles.[21]

The editors of Britannica also said that while the Nature study showed that the rate of error between the two encyclopedias was similar, the errors in a Wikipedia article usually were errors of fact, while the errors in a Britannica article were errors of omission. According to the editors of Britannica, Britannica was more accurate than Wikipedia in that respect.[20] Subsequently, Nature magazine rejected the Britannica response with a rebuttal of the editors' specific objections about the research method of the study.[22][23]

Lack of methodical fact-checking

Inaccurate information that is not obviously false may persist in Wikipedia for a long time before it is challenged. The most prominent cases reported by mainstream media involved biographies of living people.

The Wikipedia Seigenthaler biography incident demonstrated that the subject of a biographical article must sometimes fix blatant lies about his own life. In May 2005, an anonymous user edited the biographical article on American journalist and writer John Seigenthaler so that it contained several false and defamatory statements.[24][25] The inaccurate claims went unnoticed from May until September 2005 when they were discovered by Victor S. Johnson Jr., a friend of Seigenthaler. Wikipedia content is often mirrored at sites such as Answers.com, which means that incorrect information can be replicated alongside correct information through a number of web sources. Such information can thereby develop false authority due to its presence at such sites.[26]

In another example, on March 2, 2007, MSNBC.com reported that then-New York Senator Hillary Clinton had been incorrectly listed for 20 months in her Wikipedia biography as having been valedictorian of her class of 1969 at Wellesley College, when she was not.[27] The article included a link to the Wikipedia edit,[28] where the incorrect information was added on July 9, 2005. The inaccurate information was removed within 24 hours after the MSNBC.com report appeared.[29]

Attempts to perpetrate hoaxes may not be confined to editing existing Wikipedia articles, but can also include creating new articles. In October 2005, Alan Mcilwraith, a call center worker from Scotland, created a Wikipedia article in which he wrote that he was a highly decorated war hero. The article was quickly identified as a hoax by other users and deleted.[30]

There have also been instances of users deliberately inserting false information into Wikipedia in order to test the system and demonstrate its alleged unreliability. Gene Weingarten, a journalist, ran such a test in 2007, in which he inserted false information into his own Wikipedia article; it was removed 27 hours later by a Wikipedia editor.[31] Wikipedia considers the deliberate insertion of false and misleading information to be vandalism.[32]

Neutral point of view and conflicts of interest

Wikipedia regards the concept of a neutral point of view as one of its non-negotiable principles; however, it acknowledges that such a concept has its limitations – its NPOV policy states that articles should be "as far as possible" written, "without editorial bias". Mark Glaser, a journalist, also wrote that this may be an impossible ideal due to the inevitable biases of editors.[33] Research has shown that articles can maintain bias in spite of the neutral point of view policy through word choice, the presentation of opinions and controversial claims as facts, and framing bias.[34][35]

In August 2007, a tool called WikiScanner—developed by Virgil Griffith, a visiting researcher from the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico—was released to match edits to the encyclopedia by non-registered users with an extensive database of IP addresses.[36] News stories appeared about IP addresses from various organizations such as the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Republican Congressional Committee, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, Diebold, Inc. and the Australian government being used to make edits to Wikipedia articles, sometimes of an opinionated or questionable nature. Another story stated that an IP address from the BBC itself had been used to vandalize the article on George W. Bush.[37] The BBC quoted a Wikipedia spokesperson as praising the tool: "We really value transparency and the scanner really takes this to another level. Wikipedia Scanner may prevent an organization or individuals from editing articles that they're really not supposed to."[38] Not everyone hailed WikiScanner as a success for Wikipedia. Oliver Kamm, in a column for The Times, argued instead that:[3]

The WikiScanner is thus an important development in bringing down a pernicious influence on our intellectual life. Critics of the web decry the medium as the cult of the amateur. Wikipedia is worse than that; it is the province of the covert lobby. The most constructive course is to stand on the sidelines and jeer at its pretensions.

WikiScanner reveals conflicts of interest only when the editor does not have a Wikipedia account and their IP address is used instead. Conflict-of-interest editing done by editors with accounts is not detected, since those edits are anonymous to everyone except some Wikipedia administrators.[39]

Scientific disputes

The 2005 Nature study also gave two brief examples of challenges that Wikipedian science writers purportedly faced on Wikipedia. The first concerned the addition of a section on violence to the schizophrenia article, which was little more than a "rant" about the need to lock people up, in the view of one of the article's regular editors, neuropsychologist Vaughan Bell. He said that editing it stimulated him to look up the literature on the topic.[17]

Another dispute involved the climate researcher William Connolley, a Wikipedia editor who was opposed by others. The topic in this second dispute was "language pertaining to the greenhouse effect",[40] and The New Yorker reported that this dispute, which was far more protracted, had led to arbitration, which took three months to produce a decision.[40] The outcome of arbitration was for Connolley to be restricted to undoing edits on articles once per day.[40]

Exposure to political operatives and advocates

While Wikipedia policy requires articles to have a neutral point of view, it is not immune from attempts by outsiders (or insiders) with an agenda to place a spin on articles. In January 2006, it was revealed that several staffers of members of the U.S. House of Representatives had embarked on a campaign to cleanse their respective bosses' biographies on Wikipedia, as well as inserting negative remarks on political opponents. References to a campaign promise by Martin Meehan to surrender his seat in 2000 were deleted, and negative comments were inserted into the articles on United States Senator Bill Frist of Tennessee, and Eric Cantor, a congressman from Virginia. Numerous other changes were made from an IP address assigned to the House of Representatives.[41] In an interview, Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales remarked that the changes were "not cool".[42]

Larry Delay and Pablo Bachelet wrote that from their perspective, some articles dealing with Latin American history and groups (such as the Sandinistas and Cuba) lack political neutrality and are written from a sympathetic Marxist perspective which treats socialist dictatorships favorably at the expense of alternative positions.[43][44]

In 2008, the pro-Israel group Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting in America (CAMERA) organized an e-mail campaign to encourage readers to correct perceived Israel-related biases and inconsistencies in Wikipedia.[45] CAMERA argued the excerpts were unrepresentative and that it had explicitly campaigned merely "toward encouraging people to learn about and edit the online encyclopedia for accuracy".[46] Defenders of CAMERA and the competing group, Electronic Intifada, went into mediation.[45] Israeli diplomat David Saranga said Wikipedia is generally fair in regard to Israel. When it was pointed out that the entry on Israel mentioned the word "occupation" nine times, whereas the entry on the Palestinian people mentioned "terror" only once, he responded, "It means only one thing: Israelis should be more active on Wikipedia. Instead of blaming it, they should go on the site much more, and try and change it."[47]

Israeli political commentator Haviv Rettig Gur, reviewing widespread perceptions in Israel of systemic bias in Wikipedia articles, has argued that there are deeper structural problems creating this bias: anonymous editing favors biased results, especially if the editors organize concerted campaigns of defamation as has been done in articles dealing with Arab-Israeli issues, and current Wikipedia policies, while well-meant, have proven ineffective in handling this.[48]

On August 31, 2008, The New York Times ran an article detailing the edits made to the biography of Alaska governor Sarah Palin in the wake of her nomination as the running mate of Arizona Senator John McCain. During the 24 hours before the McCain campaign announcement, 30 edits, many of them adding flattering details, were made to the article by the user "Young_Trigg".[49] This person later acknowledged working on the McCain campaign, and having several other user accounts.[50]

In November 2007, libelous accusations were made against two politicians from southwestern France, Jean-Pierre Grand and Hélène Mandroux-Colas, on their Wikipedia biographies. Grand asked the president of the French National Assembly and Prime Minister to reinforce the legislation on the penal responsibility of Internet sites and of authors who peddle false information in order to cause harm.[51] Senator Jean Louis Masson then requested the Minister of Justice to tell him whether it would be possible to increase the criminal responsibilities of hosting providers, site operators, and authors of libelous content; the minister declined to do so, recalling the existing rules in the LCEN law (see Internet censorship in France).[52]

On August 25, 2010, the Toronto Star reported that the Canadian "government is now conducting two investigations into federal employees who have taken to Wikipedia to express their opinion on federal policies and bitter political debates."[53]

In 2010, Al Jazeera's Teymoor Nabili suggested that the article Cyrus Cylinder had been edited for political purposes by "an apparent tussle of opinions in the shadowy world of hard drives and 'independent' editors that comprise the Wikipedia industry." He suggested that after the Iranian presidential election of 2009 and ensuing "anti-Iranian activities", a "strenuous attempt to portray the cylinder as nothing more than the propaganda tool of an aggressive invader" was visible. The edits following his analysis of the edits during 2009 and 2010, represented "a complete dismissal of the suggestion that the cylinder, or Cyrus' actions, represent a concern for human rights or any kind of enlightened intent," in stark contrast to Cyrus' own reputation as documented in the Old Testament and the people of Babylon.[54]

Commandeering or sanitizing articles

Articles of particular interest to an editor or group of editors are sometimes modified based on these editors' respective points of views.[55] Some companies and organizations—such as Sony, Diebold, Nintendo, Dell, the CIA, and the Church of Scientology—as well as individuals, such as United States Congressional staffers, were all shown to have modified the Wikipedia pages about themselves in order to present a point of view that describes them positively; these organizations may have editors who revert negative changes as soon as these changes are submitted.[56][57]

The Chinese Wikipedia article on the Tiananmen Square massacre was rewritten to describe it as necessary to "quell the counterrevolutionary riots" and Taiwan was described as "a province in the People's Republic of China". According to the BBC, "there are indications that [such edits] are not all necessarily organic, nor random" and were in fact encouraged by the Chinese government.[58][59]

Quality of writing

.png.webp)

In a 2006 mention of Jimmy Wales, Time magazine stated that the policy of allowing anyone to edit had made Wikipedia the "biggest (and perhaps best) encyclopedia in the world".[60]

In 2008, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University found that the quality of a Wikipedia article would suffer rather than gain from adding more writers when the article lacked appropriate explicit or implicit coordination.[61] For instance, when contributors rewrite small portions of an entry rather than making full-length revisions, high- and low-quality content may be intermingled within an entry. Roy Rosenzweig, a history professor, stated that American National Biography Online outperformed Wikipedia in terms of its "clear and engaging prose", which, he said, was an important aspect of good historical writing.[62] Contrasting Wikipedia's treatment of Abraham Lincoln to that of Civil War historian James McPherson in American National Biography Online, he said that both were essentially accurate and covered the major episodes in Lincoln's life, but praised "McPherson's richer contextualization ... his artful use of quotations to capture Lincoln's voice ... and ... his ability to convey a profound message in a handful of words." By contrast, he gives an example of Wikipedia's prose that he finds "both verbose and dull". Rosenzweig also criticized the "waffling—encouraged by the NPOV policy—[which] means that it is hard to discern any overall interpretive stance in Wikipedia history". While generally praising the article on William Clarke Quantrill, he quoted its conclusion as an example of such "waffling", which then stated: "Some historians ... remember him as an opportunistic, bloodthirsty outlaw, while others continue to view him as a daring soldier and local folk hero."[62]

Other critics have made similar charges that, even if Wikipedia articles are factually accurate, they are often written in a poor, almost unreadable style. Frequent Wikipedia critic Andrew Orlowski commented, "Even when a Wikipedia entry is 100 percent factually correct, and those facts have been carefully chosen, it all too often reads as if it has been translated from one language to another then into a third, passing an illiterate translator at each stage."[63] A comparative study of Wikipedia, Britannica and Simple Wikipedia in 2012 by Adam Jatowt and Katsumi Tanaka [64] using a range of readability metrics on a subset of 90k articles from Britannica and 25k articles from both Wikipedia and Simple Wikipedia, revealed that Britannica tends to have articles that are 21% easier to read than Wikipedia, while Simple Wikipedia is on average 26% easier than Wikipedia. The authors attributed these differences to the fact that Wikipedia articles have multiple authors who may rarely collaborate towards a readable and coherent text unlike the case of Britannica. A study of Wikipedia articles on cancer was conducted in 2010 by Yaacov Lawrence of the Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University. The study was limited to those articles that could be found in the Physician Data Query and excluded those written at the "start" class or "stub" class level. Lawrence found the articles accurate but not very readable, and thought that "Wikipedia's lack of readability (to non-college readers) may reflect its varied origins and haphazard editing".[65] The Economist argued that better-written articles tend to be more reliable: "inelegant or ranting prose usually reflects muddled thoughts and incomplete information".[66]

The Wall Street Journal debate

In the September 12, 2006, edition of The Wall Street Journal, Jimmy Wales debated with Dale Hoiberg, editor-in-chief of Encyclopædia Britannica.[67] Hoiberg focused on a need for expertise and control in an encyclopedia and cited Lewis Mumford that overwhelming information could "bring about a state of intellectual enervation and depletion hardly to be distinguished from massive ignorance." Wales emphasized Wikipedia's differences and asserted that openness and transparency lead to quality. Hoiberg said he "had neither the time nor space to respond to [criticisms]" and "could corral any number of links to articles alleging errors in Wikipedia", to which Wales responded: "No problem! Wikipedia to the rescue with a fine article", and included a link to the Wikipedia article about criticism of Wikipedia.[67]

Systemic bias in coverage

Wikipedia has been accused of systemic bias, which is to say its general nature leads, without necessarily any conscious intention, to the propagation of various prejudices. Although many articles in newspapers have concentrated on minor factual errors in Wikipedia articles, there are also concerns about large-scale, presumably unintentional effects from the increasing influence and use of Wikipedia as a research tool at all levels. In an article in the Times Higher Education magazine (London), philosopher Martin Cohen describes Wikipedia as having "become a monopoly" with "all the prejudices and ignorance of its creators," which he calls a "youthful cab-drivers" perspective.[68] Cohen concludes that "[t]o control the reference sources that people use is to control the way people comprehend the world. Wikipedia may have a benign, even trivial face, but underneath may lie a more sinister and subtle threat to freedom of thought."[68] That freedom is undermined by what he sees as what matters on Wikipedia, "not your sources but the 'support of the community."[68]

Researchers from Washington University in St. Louis developed a statistical model to measure systematic bias in the behavior of Wikipedia's users regarding controversial topics. The authors focused on behavioral changes of the encyclopedia's administrators after assuming the post, writing that systematic bias occurred after the fact.[69]

Critics also point to the tendency to cover topics in detail disproportionate to their importance. For example, Stephen Colbert once mockingly praised Wikipedia for having a longer entry on 'lightsabers' than it does on the 'printing press'.[70] Dale Hoiberg, the editor-in-chief of Encyclopædia Britannica, said "People write of things they're interested in, and so many subjects don't get covered, and news events get covered in great detail. In the past, the entry on Hurricane Frances was more than five times the length of that on Chinese art, and the entry on Coronation Street was twice as long as the article on Tony Blair."[13]

This approach of comparing two articles, one about a traditionally encyclopedic subject and the other about one more popular with the crowd, has been called "wikigroaning".[71][72][73] A defense of inclusion criteria is that the encyclopedia's longer coverage of pop culture does not deprive the more "worthy" or serious subjects of space.[74]

Notability of article topics

Wikipedia's notability guidelines, which are used by editors to determine if a subject merits its own article, and the application thereof, are the subject of much criticism.[75] In May 2018, a Wikipedia editor rejected a draft article about Donna Strickland before she won the Nobel Prize in Physics in November of the same year, because no independent sources were given to show that Strickland was sufficiently notable by Wikipedia's standards. Journalists highlighted this as an indicator of the limited visibility of women in science compared to their male colleagues.[76][77]

The gender bias on Wikipedia is well documented and has prompted a movement to increase the number of notable women on Wikipedia through the Women in Red WikiProject. In an article entitled "Seeking Disambiguation", Annalisa Merelli interviewed Catalina Cruz, a candidate for office in Queens, New York in the 2018 election who had the notorious SEO disadvantage of having the same name as a porn star with a Wikipedia page. Merelli also interviewed the Wikipedia editor who wrote the candidate's ill-fated article (which was deleted, then restored, after she won the election). She described the Articles for Deletion process and pointed to other candidates who had pages on the English Wikipedia despite never having held office.[78]

Novelist Nicholson Baker, critical of deletionism, writes: "There are quires, reams, bales of controversy over what constitutes notability in Wikipedia: nobody will ever sort it out."[79]

Journalist Timothy Noah wrote of his treatment: "Wikipedia's notability policy resembles U.S. immigration policy before 9/11: stringent rules, spotty enforcement". In the same article, Noah mentions that the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Stacy Schiff was not considered notable enough for a Wikipedia entry until she wrote her article "Know it All" about the Wikipedia Essjay controversy.[80]

On a more generic level, a 2014 study found no correlation between the characteristics of a given Wikipedia page about an academic and the academic's notability as determined by citation counts. The metrics of each Wikipedia page examined included length, number of links to the page from other articles, and number of edits made to the page. This study also found that Wikipedia did not cover notable ISI highly cited researchers properly.[81]

In 2020, Wikipedia was criticized for the amount of time it took for an article about Theresa Greenfield, a candidate for the 2020 United States Senate election in Iowa, to leave Wikipedia's Articles for Creation process and become published. Particularly, the criteria for notability were criticized, with The Washington Post reporting: "Greenfield is a uniquely tricky case for Wikipedia because she doesn't have the background that most candidates for major political office typically have (like prior government experience or prominence in business). Even if Wikipedia editors could recognize she was prominent, she had a hard time meeting the official criteria for notability."[82] Jimmy Wales also criticized the long process on his talk page.[83]

Partisanship

According to Haaretz, "Wikipedia has succeeded in being accused of being both too liberal and too conservative, and has critics from across the spectrum.", while also noting that Wikipedia is "usually accused of being too liberal".[84] According to CNN, Wikipedia's ideological bias "may match the ideological bias of the news ecosystem."[85]

U.S. commentators, mostly politically conservative ones, have suggested that a politically liberal viewpoint is predominant in the English Wikipedia. Andrew Schlafly created Conservapedia because of his perception that Wikipedia contained a liberal bias.[86] Conservapedia's editors have compiled a list of alleged examples of liberal bias in Wikipedia.[87] In 2007, an article in The Christian Post criticised Wikipedia's coverage of intelligent design, saying it was biased and hypocritical.[88] Lawrence Solomon of National Review considered the Wikipedia articles on subjects like global warming, intelligent design, and Roe v. Wade all to be slanted in favor of liberal views.[89] In a September 2010 issue of the conservative weekly Human Events, Rowan Scarborough presented a critique of Wikipedia's coverage of American politicians prominent in the approaching U.S. midterm elections as evidence of systemic liberal bias. Scarborough compares the biographical articles of liberal and conservative opponents in Senate races in the Alaska Republican primary and the Delaware and Nevada general election, emphasizing the quantity of negative coverage of Tea Party movement-endorsed candidates. He also cites criticism by Lawrence Solomon and quotes in full the lead section of Wikipedia's article on Conservapedia as evidence of an underlying bias.[90]

In 2006, Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales said: "The Wikipedia community is very diverse, from liberal to conservative to libertarian and beyond. If averages mattered, and due to the nature of the wiki software (no voting) they almost certainly don't, I would say that the Wikipedia community is slightly more liberal than the U.S. population on average, because we are global and the international community of English speakers is slightly more liberal than the U.S. population. There are no data or surveys to back that."[91] In 2007, Wales said that claims of liberal bias on Wikipedia "are not supported by the facts".[92] Shane Greenstein and Feng Zhu analyzed 2012 era Wikipedia articles on U.S. politics, going back a decade, and wrote a study[93] arguing the more contributors there were to an article, the less biased the article would be, and that – based on a study of frequent collocations – fewer articles "leaned Democrat" than was the case in Wikipedia's early years.[94][95] Sorin Adam Matei, a professor at Purdue University, said that "for certain political topics, there's a central-left bias. There's also a slight when it comes to more political topics, counter-cultural bias. It's not across the board, and it's not for all things."[96]

In February 2021, Fox News accused Wikipedia of whitewashing communism and socialism.[97] In November 2021, the English Wikipedia's entry for "Mass killings under communist regimes" was nominated for deletion, with some editors arguing that it has "a biased 'anti-Communist' point of view", that "it should not resort to 'simplistic presuppositions that events are driven by any specific ideology'", and that "by combining different elements of research to create a 'synthesis', this constitutes original research and therefore breaches Wikipedia rules."[98] This was criticized by historian Robert Tombs, who called it "morally indefensible, at least as bad as Holocaust denial, because 'linking ideology and killing' is the very core of why these things are important. I have read the Wikipedia page, and it seems to be careful and balanced. Therefore, attempts to remove it can only be ideologically motivated – to whitewash Communism."[98] Other Wikipedia editors and users on social media opposed the deletion of the article.[99] The article's deletion nomination received considerable attention from conservative media.[100] The Heritage Foundation, an American conservative think tank, called the arguments made in favor of deletion "absurd and ahistorical".[100] On December 1, 2021, a panel of four administrators found that the discussion yielded no consensus, meaning that the status quo was retained, and the article was not deleted.[101] The article's deletion discussion was the largest in Wikipedia's history.[100]

Hindutvas have accused Wikipedia of being anti-Hindu and anti-Indian.[102][103]

National or corporate bias

In 2008, Tim Anderson, a senior lecturer in political economy at the University of Sydney, said Wikipedia administrators display an American-focused bias in their interactions with editors and their determinations of which sources are appropriate for use on the site. Anderson was outraged after several of the sources he used in his edits to the Hugo Chávez article, including Venezuela Analysis and Z Magazine, were disallowed as "unusable". Anderson also described Wikipedia's neutral point of view policy to ZDNet Australia as "a facade" and that Wikipedia "hides behind a reliance on corporate media editorials".[104]

Racial bias

Wikipedia has been charged with having a systemic racial bias in its coverage, due to an underrepresentation of people of colour as editors.[105] The President of Wikimedia D.C., James Hare, noted that "a lot of black history is left out" of Wikipedia, due to articles predominately being written by white editors.[106] Articles that do exist on African topics are, according to some critics, largely edited by editors from Europe and North America and thus reflect their knowledge and consumption of media, which "tend to perpetuate a negative image" of Africa.[107] Maira Liriano, of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, has argued that the lack of information regarding black history on Wikipedia "makes it seem like it's not important."[108] San Francisco Poet Laureate Alejandro Murguía has stressed how it is important for Latinos to be part of Wikipedia "because it is a major source of where people get their information."[109] In 2010, an analysis of Wikipedia edits revealed that Asia, as the most populous continent, was represented in only 16.67% of edits. Africa (6.35%) and South America (2.58%) were equally underrepresented.[110]

In 2018, the Southern Poverty Law Center criticized Wikipedia for being "vulnerable to manipulation by neo-Nazis, white nationalists and racist academics seeking a wider audience for extreme views."[111] According to the SPLC, "[c]ivil POV-pushers can disrupt the editing process by engaging other users in tedious and frustrating debates or tie up administrators in endless rounds of mediation. Users who fall into this category include racialist academics and members of the human biodiversity, or HBD, blogging community. ... In recent years, the proliferation of far-right online spaces, such as white nationalist forums, alt-right boards and HBD blogs, has created a readymade pool of users that can be recruited to edit on Wikipedia en masse. ... The presence of white nationalists and other far-right extremists on Wikipedia is an ongoing problem that is unlikely to go away in the near future given the rightward political shift in countries where the majority of the site's users live."[111] The SPLC cited the article "Race and intelligence" as an example of the alt-right influence on Wikipedia, stating that at that time the article presented a "false balance" between fringe racialist views and the "mainstream perspective in psychology."[111] In 2022 The Chronicle of Higher Education reported on a researcher at Cleveland State University whose "home institution was essentially providing a soapbox for racist pseudoscience." The article states that he had some influence on "public misperceptions of race" as a result of heavy editing of an early version of Wikipedia's article on race and intelligence.[112]

Gender bias and sexism

Wikipedia has a longstanding controversy concerning gender bias and sexism.[114][115][116][117][118][119] Gender bias on Wikipedia refers to the finding that between 84 and 91 percent of Wikipedia editors are male,[120][121] which allegedly leads to systemic bias.[122] Wikipedia has been criticized[114] by some journalists and academics for lacking not only women contributors but also extensive and in-depth encyclopedic attention to many topics regarding gender. Sue Gardner, former executive director of the Foundation, said that increasing diversity was about making the encyclopedia "as good as it could be". Factors cited as possibly discouraging women from editing included the "obsessive fact-loving realm", associations with the "hard-driving hacker crowd", and the necessity to be "open to very difficult, high-conflict people, even misogynists."[115]

In 2011, the Wikimedia Foundation set a goal of increasing the proportion of female contributors to 25 percent by 2015.[115] In August 2013, Gardner conceded defeat: "I didn't solve it. We didn't solve it. The Wikimedia Foundation didn't solve it. The solution won't come from the Wikimedia Foundation."[123] In August 2014, Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales acknowledged in a BBC interview the failure of Wikipedia to fix the gender gap and announced the Wikimedia Foundation's plans for "doubling down" on the issue. Wales said the Foundation would be open to more outreach and more software changes.[124]

Writing in the Notices of the American Mathematical Society, Marie Vitulli states that "mathematicians have had a difficult time when writing biographies of women mathematicians," and she describes the aggressiveness of editors and administrators in deleting such articles.[125]

Criticism was presented on this topic in The Signpost (WP:THREATENING2MEN).[126]

Institutional bias

Wikipedia has been criticized for reflecting the bias and influence of media that are seen as reliable due to their dominance, and for being a site of conflict between entrenched or special institutional interests. Public relations firms and interest lobbies, corporate, political and otherwise, have been accused of working systemically to distort Wikipedia's articles in their respective interests.[127]

Firearms-related articles

Wikipedia has been criticized for issues related to bias in firearms-related articles. According to critics, systematic bias arises from the tendency of the editors most active in maintaining firearms-related articles to also be gun enthusiasts, and firearms-related articles are dominated by technical information while issues of the social impact and regulation of firearms are relegated to separate articles. Communications were facilitated by a "WikiProject," called "WikiProject Firearms", an on-wiki group of editors with a common interest. The alleged pro-gun bias drew increased attention after the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, in February 2018. The Wikimedia Foundation defended itself from allegations of being host to opinion-influencing campaigns of pro-gun groups, saying that the contents are always being updated and improved.[128][129][130][131][132][133][134]

Skeptical bias

In 2014, supporters of holistic healing and energy psychology began a Change.org petition asking for "true scientific discourse" on Wikipedia, complaining that "much of the information [on Wikipedia] related to holistic approaches to healing is biased, misleading, out-of-date, or just plain wrong". In response, Jimmy Wales said Wikipedia covers only works that are published in respectable scientific journals.[135][136]

Wikipedia has been accused of being biased against views outside of the scientific mainstream due to influence from the skeptical movement.[35] Social scientist Brian Martin examined the influence of skeptics on Wikipedia by looking for parallels between Wikipedia entries and characteristic techniques used by skeptics, finding that the result "does not prove that Skeptics are shaping Wikipedia but is compatible with that possibility."[35]

Sexual content

Wikipedia has been criticized for allowing graphic sexual content such as images and videos of masturbation and ejaculation as well as photos from hardcore pornographic films found on its articles. Child protection campaigners say graphic sexual content appears on many Wikipedia entries, displayed without any warning or age verification.[137]

The Wikipedia article Virgin Killer—a 1976 album from German heavy metal band Scorpions—features a picture of the album's original cover, which depicts a naked prepubescent girl. In December 2008, the Internet Watch Foundation, a nonprofit, nongovernment-affiliated organization, added the article to its blacklist, criticizing the inclusion of the picture as "distasteful". As a result, access to the article was blocked for four days by most Internet service providers in the United Kingdom.[138] Seth Finkelstein writing for The Guardian argues that the debate over the album cover masks a structural lack of accountability on Wikipedia, in particular when it comes to sexual content.[139] For example, the deletion by Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales of images of lolicon versions of the character Wikipe-tan created a minor controversy on the topic. The deletion was taken as endorsement of the non-lolicon images of Wikipe-tan, which Wales later had to explicitly deny: "I don't like Wikipe-tan and never have."[140] Finkelstein sees Wikipedia as composed of fiefdoms, which makes it difficult for the Wikipedia community to deal with such issues, and sometimes necessitates top-down intervention.[139] The prevalence of displayed unexpected pornographic content when porn-unrelated search terms are entered on the connected site Wikimedia Commons is also a subject of criticism.[141]

Exposure to vandals

As an online encyclopedia that almost anyone can edit, Wikipedia has had problems with vandalism of articles, which range from blanking articles to inserting profanities, hoaxes, or nonsense. Wikipedia has a range of tools available to users and administrators in order to fight against vandalism, including blocking and banning vandals and automated bots that detect and repair vandalism. Supporters of the project argue that the vast majority of vandalism on Wikipedia is reverted within a short time, and a study by Fernanda Viégas of the MIT Media Lab and Martin Wattenberg and Kushal Dave of IBM Research found that most vandal edits were reverted within around five minutes; however, they state that "it is essentially impossible to find a crisp definition of vandalism."[142] While most instances of page blanking or the addition of offensive material are soon reverted, less obvious vandalism, or vandalism to a little-viewed article, has remained for longer periods.

A 2007 conference paper estimated that 1 in 271 articles had some "damaged" content. Most of the damage involved nonsense; 20% involved actual misinformation. It reported that 42% of damage gets repaired before any reader clicked on the article, and 80% before 30 people did so.[143]

Privacy concerns

Most privacy concerns refer to cases of government or employer data gathering, computer or electronic monitoring; or trading data between organizations. According to James Donnelly and Jenifer Haeckel, "the Internet has created conflicts between personal privacy, commercial interests and the interests of society at large".[144] Balancing the rights of all concerned as technology alters the social landscape will not be easy. It "is not yet possible to anticipate the path of the common law or governmental regulation" regarding this problem.[144]

The concern in the case of Wikipedia is the right of a private citizen to remain private; to remain a "private citizen" rather than a "public figure" in the eyes of the law.[145] It is somewhat of a battle between the right to be anonymous in cyberspace and the right to be anonymous in real life ("meatspace"). A particular problem occurs in the case of an individual who is relatively unimportant and for whom there exists a Wikipedia page against their wishes.

In 2005, Agence France-Presse quoted Daniel Brandt, the Wikipedia Watch owner, as saying that "the basic problem is that no one, neither the trustees of Wikimedia Foundation, nor the volunteers who are connected with Wikipedia, consider themselves responsible for the content."[146]

In January 2006, a German court ordered the German Wikipedia shut down within Germany because it stated the full name of Boris Floricic, aka "Tron", a deceased hacker who was formerly with the Chaos Computer Club. More specifically, the court ordered that the URL within the German .de domain (http://www.wikipedia.de/) may no longer redirect to the encyclopedia's servers in Florida at http://de.wikipedia.org although German readers were still able to use the US-based URL directly, and there was virtually no loss of access on their part. The court order arose out of a lawsuit filed by Floricic's parents, demanding that their son's surname be removed from Wikipedia. The next month on February 9, 2006, the injunction against Wikimedia Deutschland was overturned, with the court rejecting the notion that Tron's right to privacy or that of his parents was being violated.[147]

Criticism of the community

Role of Jimmy Wales

The community of Wikipedia editors has been criticized for placing an irrational emphasis on Jimmy Wales as a person. Wales's role in personally determining the content of some articles has also been criticized as contrary to the independent spirit that Wikipedia supposedly has gained.[148][149] In early 2007, Wales dismissed the criticism of the Wikipedia model: "I am unaware of any problems with the quality of discourse on the site. I don't know of any higher-quality discourse anywhere."[150][151][152][153][154]

Conflict of interest cases

A Business Insider article wrote about a controversy in September 2012 where two Wikimedia Foundation employees were found to have been "running a PR business on the side and editing Wikipedia on behalf of their clients."[155]

Unfair treatment of women

In 2015, The Atlantic published a story by Emma Paling about a contributor who was able to obtain no relief from the Arbitration Committee for off-site harassment. Paling quotes a then-sitting Arbitrator speaking about bias against women on the Arbitration Committee.[156]

In the online magazine Slate, David Auerbach criticized the Arbitration Committee's decision to block a woman indefinitely without simultaneously blocking her "chief antagonists" in the December 2014 Gender Gap Task Force case. He mentions his own experience with what he calls "the unblockable"—abrasive editors who can get away with complaints against them because there are enough supporters, and that he had observed a "general indifference or even hostility to an outside opinion" on the English Wikipedia. Auerbach considers the systematic defense of vulgar language use by insiders as a symptom of the toxicity he describes.[157]

In January 2015, The Guardian reported that the Arbitration Committee had banned five feminist editors from gender-related articles on a case related to the Gamergate controversy while including quotes from a Wikipedia editor alleging unfair treatment.[158][159] Other commentators, including from Gawker and ThinkProgress, provided additional analysis while sourcing from The Guardian's story.[159][160][161][162][163] Reports in The Washington Post, Slate and Social Text described these articles as "flawed" or factually inaccurate, pointing out that the Arbitration case had not concluded as at the time of publishing; no editor had been banned.[159][164][165] After the result was published, Gawker wrote that "ArbCom ruled to punish six editors who could be broadly classified as 'anti-Gamergate' and five who are 'pro-Gamergate'." All of the supposed "Five Horsemen" were among the editors punished, with one of them being the sole editor banned due to this case.[166] An article called "ArbitrationGate" regarding this situation was created (and quickly deleted) on Wikipedia, while The Guardian later issued a correction to their article.[159] The Committee and the Wikimedia Foundation issued press statements that the Gamergate case was in response to the atmosphere of the Gamergate article resembling a "battlefield" due to "various sides of the discussion [having] violated community policies and guidelines on conduct", and that the committee was fulfilling its role to "uphold a civil, constructive atmosphere" on Wikipedia. The committee also wrote that it "does not rule on the content of articles, or make judgements on the personal views of parties to the case".[164][167] Michael Mandiberg, writing in Social Text, remained unconvinced.[165]

Croatian Wikipedia

On the Croatian Wikipedia, a group of administrators were criticized for blocking Wikipedians who were in favor of LGBT rights.[168][169][170] In an interview given to Index.hr, Robert Kurelić, a professor of history at the Juraj Dobrila University of Pula, has commented that "the Croatian Wikipedia is only a tool used by its administrators to promote their own political agendas, giving false and distorted facts".[171] As two particularly prominent examples he listed the Croatian Wikipedia's coverage of Istrianism (a regionalist movement in Istria, a region mostly located in Croatia), defined as a "movement fabricated to reduce the number of Croats", and antifašizam (anti-fascism), which according to him is defined as the opposite of what it really means.[171] Kurelić further advised "that it would be good if a larger number of people got engaged and started writing on Wikipedia", because "administrators want to exploit high-school and university students, the most common users of Wikipedia, to change their opinions and attitudes, which presents a serious issue".[171]

In 2013, Croatia's Minister of Science, Education and Sports at the time, Željko Jovanović, called for pupils and students in Croatia to avoid using the Croatian Wikipedia.[168] In an interview given to Novi list, Jovanović said that

"the idea of openness and relevance as a knowledge source that Wikipedia could and should represent has been completely discredited – which, for certain, has never been the goal of Wikipedia's creators nor the huge number of people around the world who share their knowledge and time using that medium. Croatian pupils and students have been wronged by this, so we have to warn them, unfortunately, that a large part of the content of the Croatian version of Wikipedia is not only dubious but also [contains] obvious forgeries, and therefore we invite them to use more reliable sources of information, which include Wikipedia in English and in other major languages of the world."[168]

Jovanović has also commented on the Croatian Wikipedia editors – calling them a "minority group that has usurped the right to edit the Croatian-language Wikipedia".[168]

Scandals involving administrators and arbitrators

David Boothroyd, a Wikipedia editor and a Labour Party (United Kingdom) member, created controversy in 2009, when Wikipedia Review contributor "Tarantino" discovered that he committed sockpuppeting, editing under the accounts "Dbiv", "Fys", and "Sam Blacketer", none of which acknowledged his real identity. After earning Administrator status with one account, then losing it for inappropriate use of the administrative tools, Boothroyd regained Administrator status with the Sam Blacketer sockpuppet account in April 2007.[172] Later in 2007, Boothroyd's Sam Blacketer account became part of the English Wikipedia's Arbitration Committee.[173] Under the Sam Blacketer account, Boothroyd edited many articles related to United Kingdom politics, including that of rival Conservative Party leader David Cameron.[174] Boothroyd then resigned as an administrator and as an arbitrator.[175][176]

Essjay controversy

In July 2006, The New Yorker ran a feature by Stacy Schiff about "a highly credentialed Wikipedia editor".[40] The initial version of the article included an interview with a Wikipedia administrator using the pseudonym Essjay, who described himself as a tenured professor of theology.[177] Essjay's Wikipedia user page, now removed, said the following:

I am a tenured professor of theology at a private university in the eastern United States; I teach both undergraduate and graduate theology. I have been asked repeatedly to reveal the name of the institution, however, I decline to do so; I am unsure of the consequences of such an action, and believe it to be in my best interests to remain anonymous.[178]

Essjay also said he held four academic degrees: Bachelor of Arts in religious studies (B.A.), Master of Arts in religion (M.A.R.), Doctorate of Philosophy in theology (Ph.D.), and Doctorate in Canon Law (JCD). Essjay specialized in editing articles about religion on Wikipedia, including subjects such as "the penitential rite, transubstantiation, the papal tiara";[40] on one occasion he was called in to give some "expert testimony" on the status of Mary in the Roman Catholic Church.[179] In January 2007, Essjay was hired as a manager with Wikia, a wiki-hosting service founded by Wales and Angela Beesley. In February, Wales appointed Essjay a member of the Wikipedia Arbitration Committee, a group with powers to issue binding rulings in disputes relating to Wikipedia.[180]

In late February 2007, The New Yorker added an editorial note to its article on Wikipedia stating that it had learned that Essjay was Ryan Jordan, a 24-year-old college dropout from Kentucky with no advanced degrees and no teaching experience.[181] Initially Jimmy Wales commented on the issue of Essjay's identity: "I regard it as a pseudonym and I don't really have a problem with it." Larry Sanger, co-founder[182][183][184] of Wikipedia, responded to Wales on his Citizendium blog by calling Wales' initial reaction "utterly breathtaking, and ultimately tragic". Sanger said the controversy "reflects directly on the judgment and values of the management of Wikipedia."[185]

Wales later issued a new statement saying he had not previously understood that "EssJay used his false credentials in content disputes." He added: "I have asked EssJay to resign his positions of trust within the Wikipedia community."[186] Sanger responded the next day: "It seems Jimmy finds nothing wrong, nothing trust-violating, with the act itself of openly and falsely touting many advanced degrees on Wikipedia. But there most obviously is something wrong with it, and it's just as disturbing for Wikipedia's head to fail to see anything wrong with it."[187]

On March 4, Essjay wrote on his user page that he was leaving Wikipedia, and he also resigned his position with Wikia.[188] A subsequent article in The Courier-Journal (Louisville) suggested that the new résumé he had posted at his Wikia page was exaggerated.[189] The March 19, 2007, issue of The New Yorker published a formal apology by Wales to the magazine and Stacy Schiff for Essjay's false statements.[190]

Discussing the incident, the New York Times noted that the Wikipedia community had responded to the affair with "the fury of the crowd", and observed:

The Essjay episode underlines some of the perils of collaborative efforts like Wikipedia that rely on many contributors acting in good faith, often anonymously and through self-designated user names. But it also shows how the transparency of the Wikipedia process—all editing of entries is marked and saved—allows readers to react to suspected fraud.[191]

The Essjay incident received extensive media coverage, including a national United States television broadcast on ABC's World News with Charles Gibson [192] and the March 7, 2007, Associated Press story.[193] The controversy has led to a proposal that users who say they possess academic qualifications should have to provide evidence before citing them in Wikipedia content disputes.[194] The proposal was not accepted.[195]

Anonymity

Wikipedia has been criticised for allowing editors to contribute anonymously (without a registered account and using an auto-generated IP-labeled account) or pseudonymously (using a registered account), with critics saying that this leads to a lack of accountability.[154][196] This also sometimes leads to uncivil conduct in debates between Wikipedians.[154][196] For privacy reasons, Wikipedia forbids editors to reveal information about another editor on Wikipedia.[197]

Criticism of process

Level of debate, edit wars, and harassment

The standard of debate on Wikipedia has been called into question by people who have noted that contributors can make a long list of salient points and pull in a wide range of empirical observations to back up their arguments, only to have them ignored completely on the site.[198] An academic study of Wikipedia articles found that the level of debate among Wikipedia editors on controversial topics often degenerated into counterproductive squabbling:

For uncontroversial, "stable" topics self-selection also ensures that members of editorial groups are substantially well-aligned with each other in their interests, backgrounds, and overall understanding of the topics ... For controversial topics, on the other hand, self-selection may produce a strongly misaligned editorial group. It can lead to conflicts among the editorial group members, continuous edit wars, and may require the use of formal work coordination and control mechanisms. These may include intervention by administrators who enact dispute review and mediation processes, [or] completely disallow or limit and coordinate the types and sources of edits.[199]

In 2008, a team from the Palo Alto Research Center found that for editors who make between two and nine edits a month, the percentage of their edits being reverted had gone from 5% in 2004 to about 15%, and people who make only one edit a month were being reverted at a 25% rate.[200] According to The Economist magazine (2008), "The behaviour of Wikipedia's self-appointed deletionist guardians, who excise anything that does not meet their standards, justifying their actions with a blizzard of acronyms, is now known as 'wiki-lawyering'."[201] In regards to the decline in the number of Wikipedia editors since the 2007 policy changes, another study stated this was partly down to the way "in which newcomers are rudely greeted by automated quality control systems and are overwhelmed by the complexity of the rule system."[10]

Another complaint about Wikipedia focuses on the efforts of contributors with idiosyncratic beliefs, who push their point of view in an effort to dominate articles, especially controversial ones.[202][203] This sometimes results in revert wars and pages being locked down. In response, an Arbitration Committee has been formed on the English Wikipedia that deals with the worst alleged offenders—though a conflict resolution strategy is actively encouraged before going to this extent. Also, to stop the continuous reverting of pages, Jimmy Wales introduced a "three-revert rule", whereby those users who reverse the effect of others' contributions to one article more than three times in a 24-hour period may be blocked.[204]

In a 2008 article in The Brooklyn Rail, Wikipedia contributor David Shankbone contended that he had been harassed and stalked because of his work on Wikipedia, had received no support from the authorities or the Wikimedia Foundation, and only mixed support from the Wikipedia community. Shankbone wrote, "If you become a target on Wikipedia, do not expect a supportive community."[205]

David Auerbach, writing in Slate magazine, said:

I am not exaggerating when I say it is the closest thing to Kafka's The Trial I have ever witnessed, with editors and administrators giving conflicting and confusing advice, complaints getting "boomeranged" onto complainants who then face disciplinary action for complaining, and very little consistency in the standards applied. In my short time there, I repeatedly observed editors lawyering an issue with acronyms, only to turn around and declare "Ignore all rules!" when faced with the same rules used against them ... The problem instead stems from the fact that administrators and longtime editors have developed a fortress mentality in which they see new editors as dangerous intruders who will wreck their beautiful encyclopedia, and thus antagonize and even persecute them.[157]

Wikipedia has also been criticized for its weak enforcement against perceived toxicities among the editing community at various times. In one case, a longtime editor was nearly driven to suicide following online abuse from editors and a ban from the site before being rescued from the suicide attempt.[206]

In order to address this problem the Wikimedia Foundation planned to institute a new rule of conduct aimed at combating 'toxic behavior'. The development of the new rule of conduct would take place in two phases. The first will include setting policies for in-person and virtual events as well as policies for technical spaces including chat rooms and other Wikimedia projects. A second phase outlining enforcement when the rules are broken is planned to be approved by the end of 2020, according to the Wikimedia board's plan.[207]

Consensus and the "hive mind"

Oliver Kamm, in an article for The Times, said Wikipedia's reliance on consensus in forming its content was dubious:[3]

Wikipedia seeks not truth but consensus, and like an interminable political meeting, the end result will be dominated by the loudest and most persistent voices.

Wikimedia advisor Benjamin Mako Hill also talked about Wikipedia's disproportional representation of viewpoints, saying:

In Wikipedia, debates can be won by stamina. If you care more and argue longer, you will tend to get your way. The result, very often, is that individuals and organizations with a very strong interest in having Wikipedia say a particular thing tend to win out over other editors who just want the encyclopedia to be solid, neutral, and reliable. These less-committed editors simply have less at stake and their attention is more distributed.[208]

Wikimedia trustee Dariusz Jemielniak says:

Tiring out one's opponent is a common strategy among experienced Wikipedians ... I have resorted to it many times.[209]

In his article, "Digital Maoism: The Hazards of the New Online Collectivism" (first published online by Edge: The Third Culture, May 30, 2006), computer scientist and digital theorist Jaron Lanier describes Wikipedia as a "hive mind" that is "for the most part stupid and boring", and asks, rhetorically, "why to pay attention to it?" His thesis says:

The problem is in the way the Wikipedia has come to be regarded and used; how it's been elevated to such importance so quickly. And that is part of the larger pattern of the appeal of a new online collectivism that is nothing less than a resurgence of the idea that the collective is all-wise, that it is desirable to have influence concentrated in a bottleneck that can channel the collective with the most verity and force. This is different from representative democracy, or meritocracy. This idea has had dreadful consequences when thrust upon us from the extreme Right or the extreme Left in various historical periods. The fact that it's now being re-introduced today by prominent technologists and futurists, people who in many cases I know and like, doesn't make it any less dangerous.[210]

Lanier also says the current economic trend is to reward entities that aggregate information, rather than those that actually generate content. In the absence of "new business models", the popular demand for content will be sated by mediocrity, thus reducing or even eliminating any monetary incentives for the production of new knowledge.[210]

Lanier's opinions produced some strong disagreement. Internet consultant Clay Shirky noted that Wikipedia has many internal controls in place and is not a mere mass of unintelligent collective effort:

Neither proponents nor detractors of hive mind rhetoric have much interesting to say about Wikipedia itself, because both groups ignore the details ... Wikipedia is best viewed as an engaged community that uses a large and growing number of regulatory mechanisms to manage a huge set of proposed edits ... To take the specific case of Wikipedia, the Seigenthaler/Kennedy debacle catalyzed both soul-searching and new controls to address the problems exposed, and the controls included, inter alia, a greater focus on individual responsibility, the very factor "Digital Maoism" denies is at work.[211]

Excessive rule-making

Various figures involved with the Wikimedia Foundation have argued that Wikipedia's increasingly complex policies and guidelines are driving away new contributors to the site. Former chair Kat Walsh was quoted in a 2009 article as criticizing the project, saying, "It was easier when I joined in 2004 ... Everything was a little less complicated ... It's harder and harder for new people to adjust."[212] Wikipedia administrator Oliver Moran views "policy creep" as the major barrier, writing that "the loose collective running the site today, estimated to be 90 percent male, operates a crushing bureaucracy with an often abrasive atmosphere that deters newcomers who might increase participation in Wikipedia and broaden its coverage".[213] According to Jemielniak, the sheer complexity of the rules and laws governing content and editor behavior has become excessive and creates a learning burden for new editors.[7][214] In 2014 Jemielniak suggested actively rewriting, and abridging, the rules and laws to decrease their complexity and size.[7][214]

Social stratification

Despite the perception that the Wikipedia process is democratic, "a small number of people are running the show",[215] including administrators, bureaucrats, stewards, checkusers, mediators, arbitrators, and oversighters.[8] In an article on Wikipedia conflicts in 2007, The Guardian discussed "a backlash among some editors, who argue that blocking users compromises the supposedly open nature of the project, and the imbalance of power between users and administrators may even be a reason some users choose to vandalise in the first place" based on the experiences of one editor who became a vandal after his edits were reverted and he was blocked for edit warring.[216]

See also

- Censorship of Wikipedia – Censorship of Wikipedia by governments

- Ideological bias on Wikipedia

- Deletionism and inclusionism in Wikipedia – Opposing philosophies within the Wikipedia community

- History of Wikipedia

- List of Wikipedia controversies – Timeline and brief descriptions of controversies involving Wikipedia

- Reliability of Wikipedia

- Predictions of the end of Wikipedia – Theories that Wikipedia will break down or become obsolete

- Wikipedia:Criticisms

- Wikipedia:List of hoaxes on Wikipedia

- Wikipedia:Press coverage

- Wikipedia:Replies to common objections

- Wikipedia:Why Wikipedia is not so great

- Wikipedia:Wikipedia is not a reliable source

References

- "Wikipedia: Articles for deletion/Klee Irwin (3rd nomination)". Wikipedia. January 15, 2014.

- Black, Edwin (April 19, 2010). "Wikipedia—The Dumbing Down of World Knowledge". History News Network. Archived from the original on September 9, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- Kamm, Oliver (August 16, 2007). "Wisdom? More like dumbness of the crowds". The Times. Archived from the original on August 14, 2011. (Author's own copy Archived September 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine)

- Messer-Kruse, Timothy (February 12, 2012). "The 'Undue Weight' of Truth on Wikipedia". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on December 18, 2016. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- "Wikipedia Experience Sparks National Debate". The BG News. Bowling Green State University. February 27, 2012. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- Colón-Aguirre, Monica; Fleming-May, Rachel A. (October 11, 2012). "'You Just Type in What You Are Looking For': Undergraduates' Use of Library Resources vs. Wikipedia" (PDF). The Journal of Academic Librarianship. p. 392. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 19, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2014. cited Fallis, Don. "Toward an Epistemology" (2008)

- Jemielniak, Dariusz (2014). Common Knowledge?: An Ethnography of Wikipedia. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804791205.

- Jemielniak, Dariusz (June 22, 2014). "The Unbearable Bureaucracy of Wikipedia: the legalistic atmosphere is making it impossible to attract and keep the new editors the site needs". Slate. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- Vergano, Dan (January 3, 2013). "Study: Wikipedia is driving away newcomers". USA Today. Archived from the original on September 21, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- Halfaker, Aaron; Geiger, R. Stuart; Morgan, Jonathan T.; Riedl, John (2012). "The Rise and Decline of an Open Collaboration System: How Wikipedia's Reaction to Popularity Is Causing Its Decline". American Behavioral Scientist. 57 (5): 664. doi:10.1177/0002764212469365. ISSN 0002-7642. S2CID 144208941.

- Petrilli, Michael J. (February 29, 2008). "Wikipedia or Wikipedia?". Education Next. Archived from the original on November 21, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- "Citing Electronic Sources". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- Waldman, Simon (October 26, 2004). "Who knows?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved December 30, 2005.

- Vallely, Paul (October 10, 2006). "The Big Question: Do we Need a More Reliable Online Encyclopedia than Wikipedia?". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on October 24, 2006. Retrieved October 18, 2006.

- Schwartz, Zach (November 11, 2015). "Wikipedia's Co-Founder Is Wikipedia's Most Outspoken Critic". Vice. Archived from the original on November 14, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

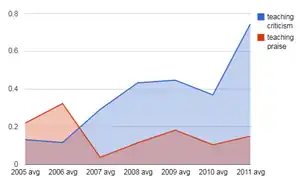

- "Research:Wikimedia Summer of Research 2011/Newbie teaching strategy trends". Meta.wikimedia.org. June 3, 2011. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- Giles, Jim (December 15, 2005). "Internet Encyclopaedias Go Head to Head". Nature. 438 (7070): 900–901. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..900G. doi:10.1038/438900a. PMID 16355180.

- "Wikipedia head to head with Britannica". ABC Science. Agence France-Presse (AFP). December 15, 2005. Archived from the original on February 16, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- Giles, J (December 22, 2005). "Supplementary Information to Accompany Nature news article 'Internet Encyclopaedias Go Head to Head'". Nature. 438 (7070): 900–901. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..900G. doi:10.1038/438900a. PMID 16355180.

- "Fatally Flawed: Refuting the Recent Study on Encyclopaedic Accuracy by the journal Nature" (PDF). Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. March 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2018. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- "Britannica attacks". Nature. 440 (7084): 582. March 30, 2006. Bibcode:2006Natur.440R.582.. doi:10.1038/440582b. PMID 16572128.

- "Wikipedia study 'fatally flawed'". BBC News. March 24, 2006. Archived from the original on August 5, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2008.

- "Encyclopædia Britannica and Nature: A Response" (PDF). Press release. March 23, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2016. Retrieved September 1, 2008.

- John Seigenthaler (November 29, 2005). "A false Wikipedia 'biography'". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- Seelye, Katharine Q. (December 3, 2005). "Snared in the Web of a Wikipedia Liar". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 7, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- "Mistakes and hoaxes on-line". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. April 15, 2006. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

- Dedman, Bill (March 3, 2007). "Reading Hillary Clinton's hidden thesis". NBC News. Archived from the original on March 6, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- "Hillary Rodham Clinton [archived version]". Wikipedia.org. July 9, 2005. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- "Hillary Rodham Clinton [archived version]". Wikipedia.org. March 2, 2007. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- Paige, Cara (April 11, 2006). "Exclusive: Meet the Real Sir Walter Mitty". Daily Record. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved November 24, 2007.

- Weingarten, Gene (March 16, 2007). "A wickedly fun test of Wikipedia". The News & Observer. Archived from the original on March 20, 2007. Retrieved April 8, 2006.

- "Wikipedia:Vandalism [archived version]". Wikipedia.org. November 24, 2009.

- Mark Glaser (April 17, 2006). "Wikipedia Bias: Is There a Neutral View on George W. Bush?". PBS. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2007.

The search for a 'neutral point of view' mirrors the efforts of journalists to be objective, to show both sides without taking sides and remaining unbiased. But maybe this is impossible and unattainable, and perhaps misguided. Because if you open it up for anyone to edit, you're asking for anything but neutrality.

- Hube, Christoph; Fetahu, Besnik (November 4–7, 2019). "Neural Based Statement Classification for Biased Language". Proceedings of the Twelfth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining. WSDM '19 Proceedings of the Twelfth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining. Melbourne VIC, Australia. pp. 259–268. arXiv:1811.05740. doi:10.1145/3289600.3291018. ISBN 978-1-4503-5940-5..

- Martin, Brian (2021) "Policing orthodoxy on Wikipedia: Skeptics in action?", Journal of Science Communication, 20:2, doi:10.22323/2.20020209

- Verkaik, Robert (August 18, 2007). "Wikipedia and the art of censorship". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- Blakely, Rhys (August 15, 2007). "Exposed: guess who has been polishing their Wikipedia entries?". The Times. London. Archived from the original on May 17, 2009. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- Fildes, Jonathan (August 15, 2007). "Wikipedia 'shows CIA page edits'". BBC. Archived from the original on January 11, 2009. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- Metz, Cade (December 18, 2007). "Truth, anonymity and the Wikipedia Way: Why it's broke and how it can be fixed". The Register. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- Schiff, Stacy (July 31, 2006). "Know it all: Can Wikipedia conquer expertise?". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on November 22, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- Lehmann, Evan (January 27, 2006). "Rewriting history under the dome". Lowell Sun. Archived from the original on February 2, 2006. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- "Senator staffers spam Wikipedia". January 30, 2006. Archived from the original on March 29, 2006. Retrieved September 13, 2006.

- Bachelet, Pablo (May 3, 2006). "War of Words: Website Can't Define Cuba". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Alt URL Archived September 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Delay, Larry (August 3, 2006). "A Pernicious Model for Control of the World Wide Web: The Cuba Case" (PDF). Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy (ASCE). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- McElroy, Damien (May 8, 2008). "Israeli battles rage on Wikipedia". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- "Letter in Harper's Magazine About Wikipedia Issues". CAMERA. August 14, 2008. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- Liphshiz, Cnaan (December 25, 2007). "Your Wiki Entry Counts". Haaretz. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- Rettig Gur, Haviv (May 16, 2010). "Israeli-Palestinian conflict rages on Wikipedia". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- Cohen, Noam (August 31, 2008). "Don't Like Palin's Wikipedia Story? Change It". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- "Sarah Palins Wikipedia entry glossed over by mystery user hrs. before VP announcement". Thaindian News. September 2, 2008. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- "Wikipédia en butte à une nouvelle affaire de calomnie". Vnunet.fr. November 28, 2007. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008.

- "Responsabilité pénale des intervenants sur Internet : hébergeur du site, responsible du site et auteur d'allégations diffamatoires". Official website of the French Sénat. February 14, 2008. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2015. [A question from Senator Jean-Louis Masson to the Minister of Justice, and the Minister's response]

- Woods, Allan (August 25, 2010). "Ottawa investigating Wikipedia edits". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on August 27, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Nabili, Teymoor (September 11, 2010). "The Cyrus Cylinder, Wikipedia and Iran conspiracies". blogs.alJazeera.net. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- Jackson, Ron (August 4, 2009). "Open Season on Domainers and Domaining — Overtly Biased L.A. Times Article Leads Latest Assault on Objectivity and Accuracy". Archived from the original on August 14, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- "Umbria Blogosphere Analysis — Wikipedia and Corporate Blogging" (PDF). J.D. Power Web Intelligence. August 24, 2007. "Organizations like Sony, Diebold, Nintendo, Dell, the CIA, and the Church of Scientology were all shown to have sanitized pages about themselves."