William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon

William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (1475 – 9 June 1511), feudal baron of Okehampton and feudal baron of Plympton,[5] was a member of the leading noble family of Devon. His principal seat was Tiverton Castle, Devon with further residences at Okehampton Castle and Colcombe Castle, also in that county.

Origins

He was the son of Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon by his wife Elizabeth Courtenay, daughter of Sir Philip Courtenay (b. 1445) of Molland, 2nd son of Sir Philip Courtenay (18 January 1404 – 16 December 1463) of Powderham by Elizabeth Hungerford, daughter of Walter Hungerford, 1st Baron Hungerford (d. 1449). William's parents were thus distant cousins, sharing a common descent from Hugh Courtenay, 10th Earl of Devon (1303–1377).

Career

William was a supporter of King Henry VII (1485–1509), the first of the Tudors, who made him a Knight Bachelor at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth on 25 November 1487. He also served in the royal army as a Captain and assisted his father in the defeat of the pretender Perkin Warbeck at the siege of Exeter in 1497, which secured the Tudor succession at last.

Attainder

However, William fell out of favour. King Henry VII discovered that he had joined in the conspiracy to crown Edmund de la Pole, 3rd Duke of Suffolk (d. 1513), the last Yorkist claimant. For his complicity, the king attainted and imprisoned him in the Tower of London in February 1504, and so made him incapable of inheritance.

Pardon and restoration

Released from prison by Henry VIII (1509–1547), Courtenay received a pardon and the restoration of his rights and privileges as a sword bearer at the coronation on 24 June 1509. It is a matter of debate as to whether he lived long enough to have been restored in his honours formally.[6] Certain sources, however, maintain that he assumed the full titles and lands of the earldom on 10 May 1511, after jousting in a tournament with the king, his cousin Sir Thomas Knyvett, and Sir William Nevill.

Marriage and issue

In October 1495 he married Catherine of York, the sixth daughter of King Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville and sister to the then-queen. William and Catherine had three children:[7]

- Henry Courtenay, 1st Marquess of Exeter (c. 1496 – 9 January 1539) married (1) Elizabeth Grey, Viscountess Lisle and (2) Gertrude Blount.[8]

- Lady Margaret Courtenay (c. 1499 – before 1526) married Henry Somerset, 2nd Earl of Worcester.[8]

- Edward Courtenay (1497 – 12 July 1502)

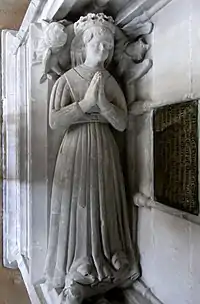

Monument to daughter

An effigy tradition identifies as "little choke-a-bone", Margaret Courtenay (d. 1512), an infant daughter of William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (1475–1511) by his wife Princess Catherine of York (d. 1527), the sixth daughter of King Edward IV (1461–1483)[7] exists in Colyton Church in Devon. The effigy is only about 3 feet in length, much smaller than usual for an adult. The face and head were renewed in 1907,[9] and is said to have been based on the sculptor's own infant daughter. One of the Courtenay seats was Colcombe Castle within the parish of Colyton. A 19th-century brass tablet above is inscribed: "Margaret, daughter of William Courtenay Earl of Devon and the Princess Katharine youngest daughter of Edward IVth King of England, died at Colcombe choked by a fish-bone AD MDXII and was buried under the window in the north transept of this church".

The effigy appears to contain errors—records show that Margaret was still alive and serving Princess Mary Tudor, daughter of Henry VIII, on 2 July 1520. However, another nobleman from that period—Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk—had named two living sons Thomas and two living daughters Elizabeth; hence, it is possible the Courtenay family had two daughters named Margaret who lived at the same time.

Heraldry

Three sculpted heraldic shields of arms exist above the effigy, showing the arms of Courtenay, Courtenay impaling the royal arms of England and the royal arms of England. Later authorities[11] have suggested, on the basis of the monument's heraldry, the effigy to be the wife of Thomas Courtenay, 5th/13th Earl of Devon (1414–1458), namely Lady Margaret Beaufort (c. 1409 – 1449), daughter of John Beaufort, 1st Marquess of Somerset, 1st Marquess of Dorset (1373–1410), KG (later only 1st Earl of Somerset) (the first of the four illegitimate children of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (4th son of King Edward III), and his mistress Katherine Swynford, later his wife) by his wife Margaret Holland. The basis of this re-attribution is the belief that the "royal arms" shown are not the arms of King Edward IV, but those of Beaufort. The arms of Beaufort are the royal arms of England differenced within a bordure compony argent and azure.[12]

Death and burial

He died of pleurisy on 9 June 1511 and was buried by a royal warrant at Blackfriars, London.

Notes and references

- No marital relationship seems to have existed between the Courtenay and Speke families but the Courtenay arms may have been displayed simply in deference to the Earl as the most powerful man in Devon. Arms: Baron: quarterly 1st & 4th Courtenay, 2nd & 3rd de Redvers (lion should be azure not sable, possible restoration error) impaling femme: royal arms of King Edward IV (1461–1483), father of his wife Catherine of York (the sixth daughter of King Edward IV by Elizabeth Woodville). The Roses surrounding the escutcheon should be the White Rose of York not the Red Rose of Lancaster as shown here possibly due to erroneous restoration. The heraldic badge above (not the Courtenay crest of a plume of ostrich feathers) seems to have been adopted during the Wars of the Roses and depicts Jupiter, king of the gods, in guise of an eagle, holding in his claws a thunderbolt, the emblem of that deity. This is a well-known image often displayed on classical Greek and Roman coins. Mediaeval nobles frequently kept classical cameos and other valuables in their cabinets as curiosities, and thus the imagery would have been familiar.

- Arnaud Bunel. "Armorial des Chevaliers de la Jarretière". Heraldique-europeenne.org. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- These arms were also borne by Katherine's uncle Edmund of York, Earl of Rutland, 1443–1460 and by her half-brother Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle (d. 1542), KG. The arms emphasise the descent of the Dukes of York from Lionel, Duke of Clarence (1338–1368), 3rd son of King Edward III, on which relationship their claim to the throne was based. http://www.richard111.com/house_of_york.htm

- Surmounted by Jupiter, king of the gods, in guise of an eagle, holding in his claws a thunderbolt, the emblem of that deity, a Courtenay heraldic emblem also visible on the chancel arch of the church above the arms of his father. The eagle is flanked by two white roses of the House of York. The sinister supporter appears to be the Courtenay dolphin. This porch was erected with a chantry chapel in 1517 by John Greenway (1460–1529), a merchant of Tiverton, whose monogram is visible in the spandrels either side of the ogee arch. He added the Courtenay heraldry to his building as a sign of deference to the powerful Earl, lord of the manor of Tiverton, whose seat of Tiverton Castle was situated adjacent to the north of the church.

- Pole, Sir William (d. 1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791, p.10

- Debrett's Peerage, 1968, p.354 states he did not live long enough to have received restoration of his honours

- Vivian, Lt. Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, p.245

- Vivian, p.245

- Barron, Oswald (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 324–326.

- raised horizontal line on top of shield is part of the label, a differencing charge shown in the Courtenay arms

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, 1911, "Courtenay"; Pevsner, Nikolaus & Cherry, Bridget, The Buildings of England: Devon, London, 2004, p.280; Hoskins, W.G., A New Survey of England: Devon, London, 1959 (first published 1954), p.373

- Barron, Oswald (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). pp. 324–326. The effigy of this grandaughter of John of Gaunt, with the shields of Courtenay and Beaufort (sic) above it, is in Colyton church. It is less than life-size, a fact which has given rise to a village legend that it represents “Little choke-a-bone,” an infant daughter of the tenth earl, who died “choked by a fish bone.” In spite of the evidence of the shields and the 15th-century dress of the effigy, the legend has now been strengthened by an inscription upon a brass plate, and in the year 1907 ignorance engaged a monumental sculptor to deface the effigy by giving its broken features the newly carved face of a young child.

Sources

- G.E. Cokayne, Complete Peerage new ed. (1910–59)

- Great Britain, and Richard Bligh. New Reports of Cases Heard in the House of Lords, On Appeals and Writs of Error. London: Saunders and Benning, 1829. googlebooks Retrieved 26 January 2008

- thepeerage.com Accessed 26 January 2008

- familysearch.org Accessed 26 January 2008