Dexter and sinister

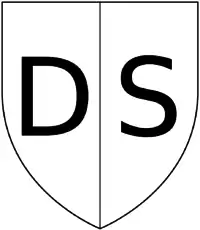

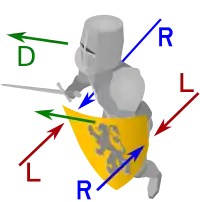

Dexter and sinister are terms used in heraldry to refer to specific locations in an escutcheon bearing a coat of arms, and to the other elements of an achievement. Dexter (Latin for 'right')[1] indicates the right-hand side of the shield, as regarded by the bearer, i.e. the bearer's proper right, and to the left as seen by the viewer. Sinister (Latin for 'left')[2] indicates the left-hand side as regarded by the bearer – the bearer's proper left, and to the right as seen by the viewer. In vexillology, the equivalent terms are hoist and fly.

Significance

The dexter side is considered the side of greater honour, for example when impaling two arms. Thus, by tradition, a husband's arms occupy the dexter half of his shield, his wife's paternal arms the sinister half. The shield of a bishop shows the arms of his see in the dexter half, his personal arms in the sinister half. King Richard II adopted arms showing the attributed arms of Edward the Confessor in the dexter half and the royal arms of England in the sinister. More generally, by ancient tradition, the guest of greatest honour at a banquet sits at the right hand of the host. The Bible is replete with passages referring to being at the "right hand" of God.

Sinister is used to indicate that an ordinary or other charge is turned to the heraldic left of the shield. A bend sinister is a bend (diagonal band) which runs from the bearer's top left to bottom right, as opposed to top right to bottom left.[3] As the shield would have been carried with the design facing outwards from the bearer, the bend sinister would slant in the same direction as a sash worn diagonally on the left shoulder. A bend (without qualification, implying a bend dexter, though the full term is never used) is a bend which runs from the bearer's top right to bottom left. In the same way, the terms per bend and per bend sinister are used to describe a heraldic shield divided by a line like a bend or bend sinister, respectively.

This division is key to dimidiation, a method of joining two coats of arms by placing the dexter half of one coat of arms alongside the sinister half of the other. In the case of marriage, the dexter half of the husband's arms would be placed alongside the sinister half of the wife's. The practice fell out of use as early as the 14th century and was replaced by impalement. In some cases, it could render the arms that are cut in half unrecognizable[4] and in some cases, it would result in a shield that looked like one coat of arms rather than a combination of two.

The Great Seal of the United States features an eagle clutching an olive branch in its dexter talon and arrows in its sinister talon, indicating the nation's intended inclination to peace. In 1945, one of the changes ordered for the similarly arranged flag of the president of the United States by President Harry S. Truman was having the eagle face towards its right (dexter, the direction of honour) and thus towards the olive branch.[5][6]

Origin

The sides of a shield were originally named for the purpose of military training of knights and soldiers long before heraldry came into use early in the 13th century so the only viewpoint that was relevant was the bearer's. The front of the purely functional shield was originally undecorated.

It is likely that the use of the shield as a defensive and offensive weapon was almost as developed as that of the sword itself and so the various positions or strokes of the shield needed to be described to students of arms. Such usage may indeed have descended directly from Roman training techniques that were spread throughout Roman Europe and then continued during the age of chivalry when heraldry came into use.

References

- Cawley, Kevin; Florin Neumann; Matt Neuberg; Lynn Nelson (2012). "Latin Dictionary and Grammar Aid". University of Notre Dame Archives. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

- Cawley, Kevin. "Latin Dictionary and Grammar Aid". Latin Word Lookup. University of Notre Dame. Retrieved 2016-07-10.

- Friar, Stephen, ed. (1987). A New Dictionary of Heraldry. London: Alphabooks Ltd./A & C Black Plc. p. 58. ISBN 0-906670-44-6.

- Woodcock, Thomas; Robinson, John Martin (1988). The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. Oxford University Press. p. 118. ISBN 0-19-211658-4.

- Truman issued Executive Order 9646 on October 25, 1945.

- Patterson, Richard Sharpe; Dougall, Richardson (1978) [1976 i.e. 1978]. The Eagle and the Shield: A History of the Great Seal of the United States. Department and Foreign Service series; 161 Department of State publication; 8900. Washington : Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, Dept. of State : for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off. p. 449. LCCN 78602518. OCLC 4268298.

In the new Coat of Arms, Seal and Flag, the Eagle not only faces to its right — the direction of honor — but also toward the olive branches of peace which it holds in its right talon. Formerly the eagle faced toward the arrows in its left talon — arrows, symbolic of war.