Attributed arms

Attributed arms are Western European coats of arms given retrospectively to persons real or fictitious who died before the start of the age of heraldry in the latter half of the 12th century. Once coats of arms were the established fashion of the ruling class, society expected a king to be armigerous (Loomis 1922, 26). Arms were assigned to the knights of the Round Table, and then to biblical figures, to Roman and Greek heroes, and to kings and popes who had not historically borne arms (Pastoreau 1997a, 258). Each author could attribute different arms for the same person, but the arms for major figures soon became fixed.

Notable arms attributed to biblical figures include the arms of Jesus based on the instruments of the Passion, and the shield of the Trinity. Medieval literature attributed coats of arms to the Nine Worthies, including Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, and King Arthur. Arms were given to many kings predating heraldry, including Edward the Confessor and William I of England. These attributed arms were sometimes used in practice as quarterings in the arms of their descendants.

History

Attributed or imaginary arms appeared in literature in the middle of the 12th century, particularly in Arthurian legends. During the generation following Chrétien de Troyes, about 40 of Arthur's knights had attributed coats of arms (Pastoreau 1997a, 259). A second stage of development occurred during the 14th and 15th centuries when Arthurian arms expanded to include as many as 200 attributed coats of arms.

During the same centuries, rolls of arms included invented arms for kings of foreign lands (Neubecker, 30). Around 1310, Jacques de Longuyon wrote the Voeux de Paon ("Vows of the Peacock"), which included a list of nine famous leaders. This list, divided into three groups of three, became known in art and literature as the Nine Worthies (Loomis 1938, 37). Each of the Nine Worthies were given a coat of arms. King David, for instance, was assigned a gold harp as a device (Neubecker, 172).

Once coats of arms were the established fashion of the ruling class, society expected a king to be armigerous (Loomis 1922, 26). In such an era, it was "natural enough to consider that suitable armorial devices and compositions should be assigned to men of mark in earlier ages" (Boutell, 18). Each author could attribute different arms for the same person, although regional styles developed, and the arms for major figures soon became fixed (Turner, 415).

Some attributed arms were incorporated into the quarterings of their descendants' arms. The quarterings for the family of Lloyd of Stockton, for instance, include numerous arms originally attributed to Welsh chieftains from the 9th century or earlier (Neubecker, 94). In a similar vein, arms were attributed to Pope Leo IX based on the later arms of his family's descendants (Turner, 415).

In the 16th and 17th centuries, additional arms were attributed to a large number of saints, kings and popes, especially those from the 11th and 12th centuries. Pope Innocent IV (1243–1254) is the first pope whose personal coat of arms is known with certainty (Pastoreau 1997a, 283–284). By the end of the 17th century, the use of attributed arms became more restrained (Neubecker, 224).

The tinctures and charges attributed to an individual in the past provide insight into the history of symbolism (Pastoreau 1997b, 87).

Arthurian heraldry

In the Arthurian legends, each knight of the Round Table is often accompanied by a heraldic description of a coat of arms. Although these arms could be arbitrary, some characters were traditionally associated with one coat or a few different coats. Early British sources such as the Historia Brittonum assign the Pendragon a white banner with a gold dragon which later becomes the Red Dragon of Wales.

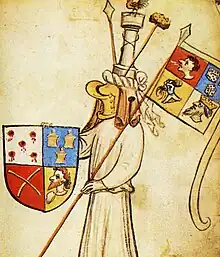

King Arthur was assigned many different arms, but from the 13th century, he was most commonly given three gold crowns on an azure field (Loomis 1938, 38). In a 1394 manuscript depicting the Nine Worthies, Arthur is shown holding a flag with three gold crowns (Neubecker, 172). The reason for the triple-crown symbol is unknown, but it was associated with other pre-Norman kings, with the seal of Magnus II of Sweden, with the relics of the Three Wise Men in Cologne (which led to the three crowns in the seal of the University of Cologne), and with the grants of Edward I of England to towns which were symbolized by three crowns in the towns' arms. The number of crowns increased to eleven, thirteen and even thirty at times (Brault, 44–46).

Other arms were associated with Arthur. In a manuscript from the later 13th century, Arthur's shield has three gold leopards, a likely heraldic flattery of Edward I of England (Brault, 22). Geoffrey of Monmouth assigned Arthur a dragon on his helmet and standard, which is possibly canting arms on Arthur's father's name, Uther Pendragon (Brault, 23). Geoffrey also assigned Arthur a shield with an image of the Virgin Mary (Brault, 24). An illustration of the latter by D. Endean Ivall, based on the battle flag described by Nennius (a cross and the Virgin Mary) and including the motto "King Arthur is not dead" in Cornish, can be found on the cover of W. H. Pascoe's 1979 A Cornish Armory.

Other characters in the Arthurian legends are described with coats of arms. Lancelot starts with plain white arms but later receives a shield with three bends gules signifying the strength of three men (Brault 47). Tristan was attributed a variety of arms. His earliest arms, a gold lion rampant on red field, are shown in a set of 13th-century tiles found in Chertsey Abbey (Loomis 1915, 308). Thomas of Britain in the 12th century attributed these arms (Loomis 1938, 47) in what is believed to be heraldic flattery of his patron, either Richard I or Henry II, whose coats of arms contained some form of lion (Loomis 1922, 26). In other versions the field is not red, but green. Gottfried von Strassburg attributed to Tristan a silver shield with a black boar rampant (Loomis 1922, 24; Loomis 1938, 49). In Italy, however, he was attributed geometric patterns (argent a bend gules per Loomis 1938, 59).

Plain arms

The Arthurian legends contain numerous instances of red knights, black knights or green knights challenging the knights of the Round Table. In most cases, the color was chosen at random and has no symbolic significance (Brault, 29). Such arms of one tincture create an atmosphere. Plain arms were rare in the 12th century, and were used in literature to suggest a primitive heraldry of a time long past. Geoffrey of Monmouth noted with favor that in the Arthurian age, worthy knights used arms of one color, suggesting 12th century heraldic ornamentation was partly pretence (Brault, 29).

Plain arms may also function as a disguise for major characters. In the Chrétien de Troyes' Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart, Lancelot bears plain red arms as a disguise. The hero of Cligès competes in a jousting tournament with plain black, green, and red arms on three successive days (Brault, 30).

Kings

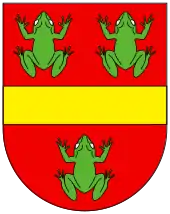

Arms were attributed to important pre-heraldic kings. Among the best known are those assigned to the King of the Franks, who was given three toads. The three fleurs-de-lis of France supposedly derive from these (Neubecker, 225).

William the Conqueror, the first Norman king of England, had a coat of arms with two lions. Richard the Lionheart used such a coat of arms with two lions on a red field (Loomis 1938, 47), from which the three lions of the coat of arms of England derive. However, there is no proof that William's arms were not attributed to William after his death (Boutell, 18).

The earlier Saxon Kings were assigned a gold cross on a blue shield, but this did not exist until the 13th century. The arms of Saint Edward the Confessor, a blue shield charged with a gold cross and five gold birds, appears to have been suggested by heralds in the time of Henry III of England (Boutell, 18) based on a coin minted in Edward's reign (Neubecker, 30). These arms were later used by Richard II of England out of devotion to the saint (Fraser, 44).

Arms were attributed to the kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon heptarchy. The Kingdom of Essex, for instance, was assigned a red shield with three notched swords (or "seaxes"). This coat was used by the counties of Essex and Middlesex until 1910, when the Middlesex County Council applied for a formal grant from the College of Arms (The Times, 1910). Middlesex was granted a red shield with three notched swords and a "Saxon Crown". The Essex County Council was granted the arms without the crown in 1932.

Even the kings of Rome were assigned arms, with Romulus, the first King of Rome, signified by the she-wolf (Neubecker, 224–225).

Flags were also attributed. While the King of Morocco was attributed three rooks as arms, which are therefore canting arms (Neubecker, 224), the whole chessboard was shown in some sources, resulting in the 14th-century checkered version of the flag of Morocco (see Flags of the World, 2007).

Religious figures

Jesus and Mary

Heralds could have attributed to Jesus the harp for arms inherited as a descendant of David. Nevertheless, the cross was regarded as Christ's emblem, and it was so used by the Crusaders. Sometimes the arms of Christ feature a Paschal lamb as the principal charge. By the 13th century, however, numerous indulgences had brought increased veneration for the instruments of the Passion. These instruments were described in heraldic terms and treated as personal to Christ much as a coat of arms (Dennys, 96). An early example in a seal from c. 1240 includes the Cross, nails, lance, crown of thorns, sponge and whips.

The instruments of the Passion were sometimes split between a shield and crest in the form of an achievement of arms (Neubecker, 222). The Hyghalmen Roll (c. 1447–1455) shows Christ holding an azure shield charged with Veronica's Veil proper. The heraldry continues with the 15th century jousting helmet, which is covered by the seamless robe as a form of mantling, and the Cross, scepter (of mockery) and flagellum (whip) as crest. The banner's long red schwenkel is a mark of eminence in German heraldry, but it was omitted when this image was copied into Randle Holme's Book (c. 1464–1480). The image on the opposing page (shown above) includes a shield quartered with the five Wounds of Christ, three jars of ointment, two rods, and the head of Judas Iscariot with a bag of money (Dennys, 97–98).

While Christ was associated with the images of the Passion, Mary was associated with images from the prophecy of Simeon the Righteous (Luke 2:34–35); the resulting attributed arms include a winged heart pierced with a sword and placed on a blue field (Dennys, 102). Mary is also attributed a group of white lily flowers. An example can be found on the lower part of the coat of arms of the College of Our Lady of Eton beside Windsor (Dennys, 103).

Trinity and angels

Out of a desire to make the abstract visible, arms were also attributed to the unseen spirits (Neubecker, 222; Dennys, 93). Because anthropomorphic representations of the Trinity were discouraged by the Church during the Middle Ages (Dennys, 95), the Shield of the Trinity quickly became popular. It was often used in decorating not only churches, but theological manuscripts and rolls of arms. An early example from William Peraldus' Summa Vitiorum (c. 1260) shows a knight battling the seven deadly sins with this shield. A variation included with the shields of arms in Matthew Paris' Chronica Majora (c. 1250–1259) adds a cross between the center and bottom circles, accompanied by the words "v'bu caro f'm est" (verbum caro factum est, "the word was made flesh"; John 1:14) (Dennys, 94).

Saint Michael the Archangel appears often in heraldic settings. In one case, the device from the shield of the Trinity is placed on a blue field and attributed to St. Michael (Dennys, 95). More usually, he is shown in armour with a red cross on a white shield, slaying the devil depicted as a dragon. These attributed arms were later transferred to Saint George (Dennys, 109).

Heraldry also attributed to Satan, as the commanding general of the fallen angels, arms to identify him in the heat of battle. The Douce Apocalypse portrays him carrying a red shield with a gold fess, and three frogs (based on Revelation 16:13) (Dennys, 112).

References

- "Armorial bearings of Middlesex". The Times. November 7, 1910.

- Charles Boutell and Arthur Charles Fox-Davies (2003). English Heraldry. Kessinger. p. 18. ISBN 0-7661-4917-X.

- Gerald J. Brault (1997). Early Blazon (2nd ed.). Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-711-4.

- Rodney Dennys (1975). The Heraldic Imagination. Barrie & Jenkins. ISBN 0-919974-01-5.

- Antonia Fraser (2000). The Lives of the Kings & Queens of England. Queens. ISBN 0-520-22460-4.

- Roger S. Loomis (1938). Arthurian Legend in Medieval Art. Modern Language Association of America.

- Roger S. Loomis (July 1915). "A Sidelight on the 'Tristan' of Thomas". Modern Language Review. 10 (3): 304–309. doi:10.2307/3712621. JSTOR 3712621.

- Roger S. Loomis (January 1922). "Tristan and the house of Anjou". Modern Language Review. 17 (1): 24–30. doi:10.2307/3714327. JSTOR 3714327.

- "Morocco Historical Flags". Flags of the World. 9 July 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- Ottfried Neubecker (1976). Heraldry: Sources, Symbols and Meaning. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-046308-5.

- Michel Pastoureau (1983). Armorial des chevaliers de la Table ronde. Leopard d'Or.

- Michel Pastoureau (1997a). Traité d'Héraldique (3e édition ed.). Picard. ISBN 2-7084-0520-9.

- Michel Pastoureau (1997). Heraldry: An Introduction to a Noble Tradition. "Abrams Discoveries" series. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-2830-2.

- Jane Turner (1996). Dictionary of Art. Vol. 14. p. 415.

External links

Media related to Imaginary heraldry at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Imaginary heraldry at Wikimedia Commons- St. Benedict's attributed arms and ecclesiastical heraldic stained glass

- Arthurian Heraldry at Heraldica.org

- King Arthur's Coat of Arms

- An Investigation into the Symbolism of Heraldry in the Legend of Tristram and Isoud

- King Arthur – Attributed Heraldry