Tabard

A tabard is a type of short coat that was commonly worn by men during the late Middle Ages and early modern period in Europe. Generally worn outdoors, the coat was either sleeveless or had short sleeves or shoulder pieces. In its more developed form it was open at the sides, and it could be worn with or without a belt. Though most were ordinary garments, often work clothes, tabards might be emblazoned on the front and back with a coat of arms (livery), and in this form they survive as the distinctive garment of officers of arms.

In modern British usage, the term has been revived for what is known in American English as a cobbler apron: a lightweight open-sided upper overgarment, of similar design to its medieval and heraldic counterpart, worn in particular by workers in the catering, cleaning and healthcare industries as protective clothing, or outdoors by those requiring high-visibility clothing. Tabards may also be worn by percussionists in marching bands in order to protect their uniforms from the straps and rigging used to support the instruments.

Middle Ages

A tabard (from the French tabarde) was originally a humble outer garment of tunic form, generally without sleeves, worn by peasants, monks and foot-soldiers. In this sense, the earliest citation recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary dates from c.1300.[1]

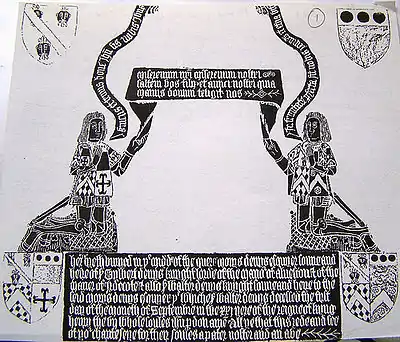

By the second half of the 15th century, tabards, now open at the sides and so usually belted, were also being worn by knights in military contexts over their armour, and were usually emblazoned with their arms (though sometimes worn plain). The Oxford English Dictionary first records this use of the word in English in 1450.[1] Tabards were apparently distinguished from surcoats by being open-sided, and by being shorter. In its later form, a tabard normally comprised four textile panels – two large panels hanging down the wearer's front and back, and two smaller panels hanging over his arms as shoulder-pieces or open "sleeves" – each emblazoned with the same coat of arms. Tabards became an important means of battlefield identification with the development of plate armour as the use of shields declined. They are frequently represented on tomb effigies and monumental brasses of the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

A very expensive, but plain, garment described as a tabard is worn by Giovanni Arnolfini in the Arnolfini Portrait of 1434 (National Gallery, London). This may be made of silk and/or velvet, and is trimmed and fully lined with fur, possibly sable.[2]

At The Queen's College, Oxford, the scholars on the foundation were called tabarders, from the tabard (not in this case an emblazoned garment) which they wore.[3]

A surviving garment similar to the medieval tabard is the monastic scapular. This is a wide strip of fabric worn front back of the body, with an opening for the head and no sleeves. It may have a hood, and may be worn under or over a belt.

British heraldry

By the end of the 16th century, the tabard was particularly associated with officers of arms. The shift in emphasis was reported by John Stow in 1598, when he described a tabard as:

a Jacquit, or sleevelesse coat, whole before, open on both sides, with a square collor, winged at the shoulders: a stately garment of olde time, commonly worne of Noble men and others, both at home and abroade in the Warres, but then (to witte in the warres) theyr Armes embrodered, or otherwise depicte uppon them, that every man by his Coate of Armes might bee knowne from others: but now these Tabardes are onely worne by the Heraults, and bee called their coates of Armes in service.[4]

In the case of Royal officers of arms, the tabard is emblazoned with the coat of arms of the sovereign. Private officers of arms, such as still exist in Scotland, make use of tabards emblazoned with the coat of arms of the person who employs them. In the United Kingdom the different ranks of officers of arms can be distinguished by the fabric from which their tabards are made. The tabard of a king of arms is made of velvet, the tabard of a herald of arms of satin, and that of a pursuivant of arms of damask silk.[5] The oldest surviving English herald's tabard is that of Sir William Dugdale as Garter King of Arms (1677–1686).[6]

It was at one time the custom for English pursuivants to wear their tabards "athwart", that is to say with the smaller ("shoulder") panels at the front and back, and the larger panels over the arms; but this practice was ended during the reign of James II and VII.[5][7]

The derisive Scots nickname of "Toom Tabard" for John Balliol (c. 1249 – 1314) may originate from either an alleged incident where his arms were stripped from his tabard in public,[8] or a reference to the Balliol arms which are a plain shield with an orle, also known as an inescutcheon voided.[9]

Canadian heraldry

In the Diamond Jubilee year of the Queen of Canada, the Governor General unveiled a new tabard for the use of the Chief Herald of Canada. This new royal blue tabard, for exclusively Canadian use and of uniquely Canadian design, is a modern take on the traditional look. The tabard differs from others of more traditional design in that the Canadian royal arms appear on the sleeves, while the front and back of the tabard are covered with Native Canadian-inspired emblematic representations of the raven-polar bears of the Canadian Heraldic Authority's coat of arms.

Gallery

Gelre Herald to the Duke of Guelders, c.1380

Gelre Herald to the Duke of Guelders, c.1380 James I, King of Scotland 1406–1437, and his wife Joan Beaufort

James I, King of Scotland 1406–1437, and his wife Joan Beaufort Tabards displaying quartered coats of arms on front and sleeves: the Denys brass of 1505, Olveston, Gloucestershire

Tabards displaying quartered coats of arms on front and sleeves: the Denys brass of 1505, Olveston, Gloucestershire Heraldic tabards worn at the funeral of Albert VII, Archduke of Austria, in Brussels in 1622

Heraldic tabards worn at the funeral of Albert VII, Archduke of Austria, in Brussels in 1622 A pursuivant wearing his tabard "athwart". A drawing by Peter Lely from the 1660s.

A pursuivant wearing his tabard "athwart". A drawing by Peter Lely from the 1660s.

Peter O'Donoghue, Bluemantle Pursuivant, photographed in 2006

Peter O'Donoghue, Bluemantle Pursuivant, photographed in 2006 A modern protective tabard worn by a bakery worker

A modern protective tabard worn by a bakery worker Orange high-visibility tabards worn by competitive motorcyclists

Orange high-visibility tabards worn by competitive motorcyclists

Cultural allusions

A tabard was the inn sign of the Tabard Inn in Southwark, London, established in 1307 and remembered as the starting point for Geoffrey Chaucer's pilgrims on their journey to Canterbury in The Canterbury Tales, dating from about the 1380s.

In E. C. Bentley's short story "The Genuine Tabard", published in his collection Trent Intervenes in 1938, a wealthy American couple purchase an antique heraldic tabard, having been told that it was worn in 1783 by Sir Rowland Verey, Garter King of Arms, when proclaiming the Peace of Versailles from the steps of St James's Palace. The amateur detective Philip Trent is able to point out that it in fact bears the post-1837 royal arms.[10]

Tabards, while not mentioned by name, feature prominently in the Touhou Project video game series, being worn by at least seven characters, ranging from minor enemies to end game bosses. The design of the characters that wear them revolves around the tabard, usually with little additional detail.

See also

References

- "tabard, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Campbell, Lorne (1998). The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Schools. National Gallery Catalogues. London: National Gallery. ISBN 185709171X.

- Farmer, John Stephen (1903). Slang and Its Analogues Past and Present: A Dictionary, Historical and Comparative, of the Heterodox Speech of All Classes of Society for More Than Three Hundred Years : with Synonyms in English, French, German, Italian, Etc. Unknown. p. 54.

- Stow, John (1598). A Survay of London. London. p. 338.

- Eirìkr Mjoksiglandi Sigurdharson (December 31, 2003). "A Review of the Historical Regalia of Officers of Arms". heraldry.sca.org. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- Marks, Richard; Payne, Ann, eds. (1978). British Heraldry: from its origins to c.1800. London: British Museum. p. 51, plate.

- Fox-Davies, A. C. (1969). Brooke-Little, J. P. (ed.). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. London: Nelson. pp. 31–2. ISBN 9780171441024.

- Young, Alan (2010). In the Footsteps of William Wallace: In Scotland and Northern England. The History Press. p. 74. ISBN 9780750951432. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- Hodgson, John; Hodgson-Hinde, John (1832). A History of Northumberland, in three parts. Printed by E. Walker. p. 124. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- Bentley, E. C. (1953) [1938]. "The genuine tabard". Trent Intervenes. London: Penguin. pp. 7–24.