William Gull

Sir William Withey Gull, 1st Baronet (31 December 1816 – 29 January 1890) was an English physician. Of modest family origins, he established a lucrative private practice and served as Governor of Guy's Hospital, Fullerian Professor of Physiology and President of the Clinical Society. In 1871, having successfully treated the Prince of Wales during a life-threatening attack of typhoid fever, he was created a Baronet and appointed to be one of the Physicians-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria.

Sir William Withey Gull, Bt | |

|---|---|

Gull c. 1860 | |

| Born | 31 December 1816 Colchester, Essex, England |

| Died | 29 January 1890 (aged 73) |

| Known for | Naming of anorexia nervosa, discovery of Gull–Sutton syndrome, seminal research into paraplegia and myxoedema |

| Spouse |

Susan Ann Lacy (m. 1848) |

| Children | Cameron Gull |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine |

| Institutions | Guy's Hospital, London |

Gull made some significant contributions to medical science, including advancing the understanding of myxoedema, Bright's disease, paraplegia and anorexia nervosa (for which he first established the name).

A masonic/royal conspiracy theory created in the 1970s alleged that Gull knew the identity of Jack the Ripper, or even that he himself was the murderer. Scholars have dismissed the idea,[2][3][4] since Gull was 71 years old and in ill health when the murders were committed. The theory has been used by creators of fictional works. Examples for his portrayal as Jack the Ripper include the films Jack the Ripper (1988) and From Hell (2001), the latter based on the graphic novel.

Childhood and early life

William Withey Gull was born on 31 December 1816 in Colchester, Essex. His father, John Gull, was a barge owner and wharfinger and was thirty-eight years old at the time of his son's birth. William was born aboard his barge The Dove, then moored at St Osyth Mill in the parish of Saint Leonards, Shoreditch. His mother's maiden name was Elizabeth Chilver and she was forty years old when William was born. William's middle name, Withey, came from his godfather, Captain Withey, a friend and employer of his father and also a local barge owner.[5] He was the youngest of eight children, two of whom died in infancy. Of William's surviving five siblings, two were brothers (John and Joseph) and three were sisters (Elizabeth, Mary and Maria).

When William was about four years old the family moved to Thorpe-le-Soken, Essex. His father died of cholera in London in 1827, when William was ten years old, and was buried at Thorpe-le-Soken. After her husband's death, Elizabeth Gull devoted herself to her children's upbringing on very slender means. She was a woman of character, instilling in her children the proverb "whatever is worth doing is worth doing well." William Gull often said that his real education had been given him by his mother. Elizabeth Gull was devoutly religious—on Fridays the children had fish and rice pudding for dinner; during Lent she wore black, and the Saints' days were carefully observed.

As a young boy, William Gull attended a local day school with his elder sisters. Later, he attended another school in the same parish, kept by the local clergyman. William was a day-boy at this school until he was fifteen, at which age he became a boarder for two years. It was at this time that he first began to study Latin. The clergyman's teaching, however, seems to have been very limited; and at seventeen William announced that he would not go any longer.

William now became a pupil-teacher in a school kept by a Mr. Abbott at Lewes, Sussex. He lived with the schoolmaster and his family, studying and teaching Latin and Greek. It was at this time that he became acquainted with Joseph Woods, the botanist, and formed an interest in looking for unusual plant life that would remain a lifelong pastime. His mother, meanwhile, had in 1832 moved to the parish of Beaumont, adjacent to Thorpe-le-Soken. After two years at Lewes, at the age of nineteen, William became restless and started to consider other careers, including working at sea.

The local rector took an interest in William and proposed that he should resume his classical and other studies on alternate days at the rectory. William agreed, and would continue this routine for a year. On his days at home, he and his sisters would row down the estuary to the sea, watching the fishermen, and collecting wildlife specimens from the nets of the coastal dredgers. William would study and catalogue the specimens thus obtained, which he would study using whatever books as he could then procure. This seems to have awoken in him an interest in biological research that would serve him well in his later career in medicine. The wish to study medicine became the fixed desire of his life.[6][7]

Early career in medicine

At about this time the local rector's uncle, Benjamin Harrison, the Treasurer of Guy's Hospital, was introduced to Gull and was impressed by his ability. He invited him to go to Guy's Hospital under his patronage and, in September 1837, the autumn before he was twenty-one, Gull left home and entered on his life's work.

It was usual for students of medicine to conduct their studies at the hospital as "apprentices." The Treasurer's patronage provided Gull with two rooms in the hospital with an annual allowance of £50 a year.

Gull, encouraged by Harrison, determined to make the most of his opportunity, and resolved to try for every prize for which he could compete in the hospital in the course of that year. He succeeded in gaining every one. During the first year of his residence at Guy's, together with his other studies he carried on his own education in Greek, Latin, and Mathematics, and in 1838 he matriculated at the recently founded University of London. In 1841 he took his M.B. degree, and gained honours in physiology, comparative anatomy, medicine, and surgery.[6][7]

Professional career

In 1842, Gull was appointed to teach materia medica at Guy's Hospital, and the Treasurer gave him a small house in King Street, with an annual salary of £100 (£14,500 in 2023). In 1843, he was appointed Lecturer on Natural Philosophy. He also held at this time the post of Medical Tutor at Guy's and, in the absence of the staff, shared with Mr. Stocker the care of the patients in the hospital. In the same year, he was appointed Medical Superintendent of the wards for lunatics, and it was largely due to his influence that these cases shortly ceased to be treated at the hospital, and the wards were converted from this use.

Throughout this period, Gull's duties gave him extensive opportunities to develop his medical experience. He spent much of his life within the wards of the hospital, at all hours of the day and often at night.

In 1846, he earned his M.D. degree at the University of London, and gained the gold medal. At that time, this was the highest honour in medicine which the University was able to confer. During his M.D. examination, he suffered an attack of nerves and was about to leave the room, saying that he knew nothing of the case proposed for comment; a friend persuaded him to return, with the result that the thesis he then wrote gained for him his Doctor's degree and the gold medal.

From 1846 to 1856, Gull held the post of Lecturer on Physiology and Comparative Anatomy at Guy's.

In 1847, Gull was elected Fullerian Professor of Physiology at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, a post which he held for two years, during which time he formed a close friendship with Michael Faraday, at that time Fullerian Professor of Chemistry. In 1848, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians. He was also appointed Resident Physician at Guy's. Dr Gull became a DCL of Oxford in 1868, a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1869, LL.D. of the University of Cambridge in 1880 and of the University of Edinburgh in 1884. He was a Crown member of the General Medical Council from 1871 to 1883, and representative of the University of London in the Council from 1886.[6][7] In 1871 he was elected President of the Clinical Society of London.[8]

Marriage and family

On 18 May 1848, Gull married Susan Ann Lacy, daughter of Colonel J. Dacre Lacy, of Carlisle. Shortly afterwards he left his rooms at Guy's and moved to 8 Finsbury Square.

They had three children: Caroline Cameron Gull was born in 1851 at Guy's Hospital and died in 1929; she married Theodore Dyke Acland MD (Oxon.) FRCP, the son of Sir Henry Acland, 1st Baronet MD FRS. They had two children, a daughter (Aimee Sarah Agnes Dyke Acland) who died in infancy in 1889, and a son, Theodore Acland (1890–1960), who became headmaster of Norwich School.

Cameron Gull was born about 1858 in Buckhold, Pangbourne, Berkshire and died in infancy.

William Cameron Gull was born on 6 January 1860 in Finsbury, Middlesex and died in 1922. He was educated at Eton College, inherited his father's title as 2nd Baronet of Brook Street, and later served as the Liberal Unionist Member of Parliament (MP) for Barnstaple from July 1895 to September 1900.

Baronet and Physician-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria

In 1871, as Physician in Ordinary to the Prince of Wales, Gull took the chief direction of the treatment of the Prince during an attack of typhoid fever.

The Prince of Wales showed the first signs of illness on 13 November 1871, while at the Royal residence at Sandringham House, Norfolk. Initially, he was attended by Dr. Lowe of Kings Lynn and by Oscar Clayton, who thought the fever was caused by a sore on a finger. After a week, with no sign of the fever abating, they diagnosed typhoid fever and sent for Gull on 21 November, and Sir William Jenner on the 23rd. It transpired that the typhoid attack was complicated by bronchitis and the Prince was in danger of his life for many days. For the next month, daily bulletins were issued by Sandringham and posted at police stations around the country. Sir William Hale-White, author of Great Doctors of the Nineteenth Century (1935), wrote: "I was a lad then and my father sent me every evening to the police station to get the latest news. It was not until just before Christmas that bulletins were issued only once a day."[9]

The following passage appeared in The Times on 18 December 1871:

'In Dr. Gull were combined energy that never tired, watchfulness that never flagged; nursing so tender, ministry so minute, that in his functions he seemed to combine the duties of physician, dresser, dispenser, valet, nurse,-now arguing with the sick man in his delirium so softly and pleasantly that the parched lips opened to take the scanty nourishment on which depended the reserves of strength for the deadly fight when all else failed, now lifting the wasted body from bed to bed, now washing the worn frame with vinegar, with ever ready eye and ear and finger to mark any change and phase, to watch face and heart and pulse, and passing at times twelve or fourteen hours at that bedside. And when these hours were over, or while they were going on-what a task for the physician !-to soothe with kindest and yet not too hopeful words her whose trial was indeed great to bear, to give counsel against despair, and yet not to justify confidence.' After the recovery of the Prince, Sir William remarked, 'He was as well treated and nursed as if he had been a patient in Guy's Hospital.'[10]

After the Prince's recovery, a service of thanksgiving was held at St Paul's Cathedral in the City of London, attended by Queen Victoria.[9] In recognition of his service, on 8 February 1872 William Gull was created the 1st Baronet of the Baronetcy of Brook Street.[11]

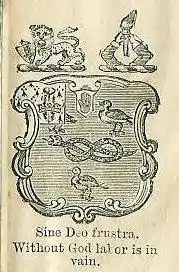

The coat of arms is shown left. The Blazon of Arms is:

Azure, a serpent nowed or between three sea-gulls proper, and for honourable augmentation a canton ermine, thereon an ostrich feather argent, quilled or, enfiled by the coronet which encircles the plume of the Prince of Wales, gold. Crests, 1st (for honourable augmentation), a lion passant guardant or, supporting with his dexter fore paw an escutcheon azure, thereon an ostrich feather argent, quilled or, enfiled with a coronet as in the canton; 2nd, two arms embowed, vested azure cuffs argent, the hands proper holding a torch or fired proper.

The Motto is:

Sine Deo Frustra (Without God, Labour Is In Vain).

Sir William Gull was appointed Physician-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria. (At this time, there were four Physicians-in-Ordinary to the Queen, each receiving an annual salary of £200. However, these were largely honorary appointments; in reality, the Queen never saw any of them except the senior physician, then Sir William Jenner, and her resident medical attendant.)[6][7][12]

Support for women in medicine

In late Victorian Britain, women were not encouraged to enter the medical profession. Sir William Gull was initially against women becoming medics but later stated that he had changed his mind and spoke out against this bias and led efforts to improve the prospects of women who wished to pursue careers in medicine.[13] In February 1886, he chaired a meeting at the Medical Society in Cavendish Square to establish a medical scholarship to be awarded to women. This was the Helen Prideaux Memorial Fund, named after Frances Helen Prideaux M.B. and B.S. Lond, a gifted University of London medical student who had died from diphtheria the previous year, having previously won the exhibition and gold medal in anatomy and gained a first class degree.[14]

Gull was reported as saying that her academic achievements answered any objections to the involvement of women in medicine; and expressed the hope that the scholarship would lead to a liberalisation of attitudes and greater recognition of women across the profession.[15]

The fund was launched with initial donations of £252 9s; Gull's personal contribution was 10 guineas (£10 10s).[16] By the mid-1890s, the scholarship was able to support a biannual prize of £50, awarded to a graduate of the London School of Medicine for Women, to assist in completing a further stage of studies.[17][18]

Illness and death

In 1887, Sir William Gull suffered the first of several strokes at his Scottish home at Urrard House, Killiecrankie. The attack of hemiplegia and aphasia was caused by a cerebral haemorrhage, of which the only warning had been unexplained haemoptysis a few days earlier. He recovered after a few weeks and returned to London, but was under no illusions about the danger to his health, remarking "One arrow had missed its mark, but there are more in the quiver".

Over the next two years, Gull lived at 74 Brook Street, Grosvenor Square, London[19] and also had homes at both Reigate and Brighton. During this period, he suffered several further strokes. The fatal attack came at his home in 74, Brook Street, London on 27 January 1890. He died two days later.

The Times newspaper carried the following report on 30 January 1890:

We regret to announce that Sir William Gull died at half-past 12 yesterday at his residence, 74, Brook-street, London, from paralysis. Sir William was seized with a severe attack of paralysis just over two years ago while staying at Urrard, Killiecrankie, and never sufficiently recovered to resume his practice. On Monday morning, after breakfast, he pointed to his mouth as if unable to speak. His valet, who was in the room, did not quite understand what was amiss, but helped him into the sitting-room. Sir William then sat down on a chair and wrote on a piece of paper, "I have no speech." The family were at once summoned, and Sir William was soon after removed to bed, where he received every attendance from Dr. Hermann Weber, an old friend, Dr. Charles D. Hood, his regular medical attendant, and Dr. Acland, his son-in-law. The patient, however, soon lost consciousness, and lingered in this state until yesterday morning, when he quietly passed away in the presence of his family. The inquiries as to his state of health during the last two days have been unusually numerous, a constant stream of carriages drawing up at the door. The Prince of Wales was kept informed of Sir William's condition through Sir Francis Knollys.[20]

The news of Gull's death was reported around the world.[21][22] American author Mark Twain observed in his diary on 1 February 1890:

Sir Wm. Gull is just dead. He nursed the Prince of Wales back to life in '71 and apparently it was for this that Mr. Gull was granted Knighthood, that doormat at the threshold of nobility. When the Prince seemed dead Mr. Gull dealt blow after blow between the shoulders, breathed into his nostrils, and literally cheated Death.[23]

Sir William Gull was buried on Monday 3 February 1890 next to the grave of his father and mother in the churchyard of his childhood home at Thorpe-le-Soken, near Colchester, Essex. A special train was commissioned to carry mourners from London. The inscription on his headstone was his favourite biblical quote:

"What doth the Lord require of thee, but to do justly, and to love mercy and to walk humbly with thy God?"

The obituary notice in the Proceedings of the Royal Society reads:

"Few men have practised a lucrative profession with less eagerness to grasp at its pecuniary rewards. He kept up the honourable standard of generosity to poor patients."

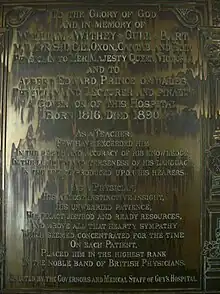

A memorial bronze plaque was placed at the entrance to Guy's Hospital Chapel. The inscription reads:

To the Glory of God and in memory of William Withey Gull, Bart M.D., F.R.S.D., C.L., Oxon., Cantab., and Edin

Physician to Her Majesty Queen Victoria and to Albert Edward, Prince of Wales

Physician and Lecturer and finally A Governor of this Hospital

Born 1816, Died 1890.

As a Teacher, Few have exceeded him In the depth and accuracy of his knowledge, In the lucidity and terseness of his language, In the effect produced upon his hearers

As a Physician, His almost instinctive insight, His unwearied patience, His exact method and ready resources,

And above all that hearty sympathy Which seemed concentrated for the time On each Patient

Placed him in the highest rank In the noble band of British Physicians

Erected by the Governors and Medical Staff of Guy's Hospital

The vacant position of Physician-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria was filled by Dr. Richard Douglas Powell, the senior of the three Physicians Extraordinary.[24]

Will, executors and bequests

Sir William Gull's will, with a codicil, was dated 27 November 1888. The value of the estate was £344,022 19s. 7d – an enormous sum at that time.

The following persons were appointed as executors: his wife, Dame Susan Anne Gull, his son, Sir William Cameron Gull, of Gloucester Street, Portman Square (the new baronet), Mr. Edmund Hobhouse, and Mr. Walter Barry Lindley.[25]

Under the terms of the will, £500 was bequeathed to each of the acting executors; £100 to Miss Mary Jackson; £100 to each of two nieces; £200 to Lady Gull's maid; £50 to Sir William's amanuensis, Miss Susan Spratt; and an annual sum of £32 10s to his butler, William Brown, for the rest of his life. A jewelled snuffbox presented to Sir William Gull by the Empress Eugénie, widow of Emperor Napoleon III of France became an entailed heirloom, along with his presentation plate.

Lady Gull was bequeathed the remainder of his plate, his pictures, furniture, and household effects and the sum of £3,000, along with the use for the remainder of her life of the house at 74 Brook Street. She also received a life annuity of £3,000, commencing 12 months after Sir William's death. Sir William's daughter Caroline received £26,000 in trust, while his son Sir William Cameron Gull received the sum of £40,000 and all the real estate.

The residue of Sir William's personal estate was to be held in trust for the purchase of real estate in England or Scotland (but not in Ireland) which was to be added to the entailed estate.[26]

Unusually, the will is recorded twice in the probate registry, in 1890 and in 1897. The text of the second entry reads:

Sir William Withey Gull of 74 Brook Street, Baronet M.D. died 29 January 1890. Probate LONDON 8 January to Edmund Hobhouse Esquire. Effects £344,022 19s 7d. Former Grant 1890.

The words "Double Probate Jan 1897" are written in the margin of the entry.[27]

Contributions to medical science

Anorexia nervosa

The term "anorexia nervosa" was first established by Sir William Gull in 1873.

In 1868, he had delivered an address to the British Medical Association at Oxford[28] in which he referred to a "peculiar form of disease occurring mostly in young women, and characterised by extreme emaciation". Gull observed that the cause of the condition could not be determined, but that cases seemed mainly to occur in young women between the ages of sixteen and twenty-three. In this address, Gull referred to the condition as Apepsia hysterica, but subsequently amended this to Anorexia hysterica and then to Anorexia nervosa.[29]

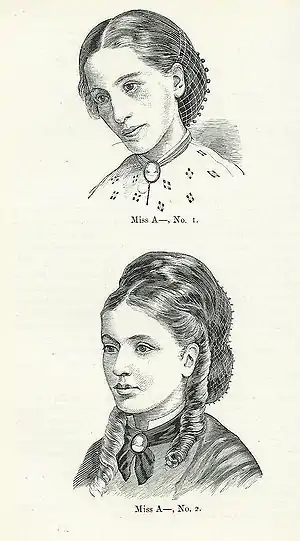

Five years later, in 1873, Gull published his work Anorexia Nervosa (Apepsia Hysterica, Anorexia Hysterica), in which he describes the three cases of Miss A, Miss B, and a third unnamed case.[30] In 1887, he also recorded the case of Miss K, in what was to be the last of his medical papers to be published.[31]

Miss A was referred to Sir William Gull by her doctor, a Mr Kelson Wright, of Clapham, London on 17 January 1866. She was aged 17 and was greatly emaciated, having lost 33 pounds. Her weight at this time was 5 stones 12 pounds (82 pounds); her height was 5 ft 5 inches. Gull records that she had suffered from amenorrhoea for nearly a year, but that otherwise her physical condition was mostly normal, with healthy respiration and heart sounds and pulse; no vomiting nor diarrhoea; clean tongue and normal urine. The pulse was slightly low at between 56 and 60. The condition was that of simple starvation, with total refusal of animal food and almost total refusal of everything else.

Gull prescribed remedies including preparations of cinchona, biochloride of mercury, syrup of iodide of iron, syrup of phosphate of iron, citrate of quinine and variations in diet without noticeable success. He observed occasional voracious appetite for very brief periods, but states that these were very rare and exceptional. He also records that she was frequently restless and active and notes that this was a "striking expression of the nervous state, for it seemed hardly possible that a body so wasted could undergo the exercise which seemed agreeable".

In Gull's published medical papers, images of Miss A are shown that depict her appearance before and after treatment (right). Gull notes her aged appearance at age 17:

It will be noticeable that as she recovered she had a much younger look, corresponding indeed to her age, twenty-one; whilst the photographs, taken when she was seventeen, give her the appearance of being nearer thirty.[32]

Miss A remained under Gull's observation from January 1866 to March 1868, by which time she seemed to have made a full recovery, having gained in weight from 82 to 128 pounds.

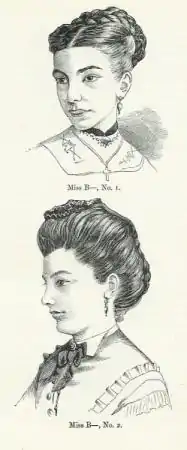

Miss B was the second case described in detail by Gull in his Anorexia nervosa paper. She was referred to Gull on 8 October 1868, aged 18, by her family who suspected tuberculosis and wished to take her to the south of Europe for the coming winter.

Gull noted that her emaciated appearance was more extreme than normally occurs in tubercular cases. His physical examination of her chest and abdomen discovered nothing abnormal, other than a low pulse of 50, but he recorded a "peculiar restlessness" that was difficult to control. The mother advised that "She is never tired". Gull was struck by the similarity of the case to that of Miss A, even to the detail of the pulse and respiration observations.

Miss B was treated by Gull until 1872, by which time a noticeable recovery was underway and eventually complete. Gull admits in his medical papers that the medical treatment probably did not contribute much to the recovery, consisting, as in the former case, of various tonics and a nourishing diet.[33]

Miss K was brought to Gull's attention by a Dr. Leachman, of Petersfield, in 1887. He records the details in the last of his medical papers to be published.[31] Miss K was aged 14 years in 1887. She was the third child in a family of six, one of whom died in infancy. Her father had died, aged 68, of pneumonic phthisis. Her mother was living and in good health; she had a sister who displayed multiple nervous symptoms and an epileptic nephew. With these exceptions, no other neurotic cases were recorded in the family. Miss K, who was described as a plump, healthy girl until the beginning of 1887, began to refuse all food except half cups of tea or coffee in February that year. She was referred to Gull and began to visit him of 20 April 1887; in his notes, he remarks that she persisted in walking through the streets to his house despite being an object of attention to passers-by. He records that she displayed no sign of organic disease; her respiration was 12 to 14; her pulse was 46; and her temperature was 97 °F. Her urine was normal. Her weight was 4 stone 7 pounds (63 pounds) and her height was 5 feet 4 inches. Miss K expressed herself to Gull as "quite well". Gull arranged for a nurse from Guy's to supervise her diet, ordering light food every few hours. After six weeks, Dr. Leachman reported good progress and by 27 July her mother reported that her recovery was almost complete, with the nurse by this time no longer being needed.

Photographs of Miss K appear in Gull's published papers. The first is dated 21 April 1887 and shows the subject in a state of extreme emaciation. The unclothed torso and head is displayed with the ribcage and clavicle clearly visible. The second photograph is dated 14 June 1887 in a similar attitude and shows a clear recovery.

Although the cases of Miss A, Miss B and Miss K resulted in recovery, Gull states that he observed at least one fatality as a result of anorexia nervosa. He states that the post mortem revealed no physical abnormalities other than thrombosis of the femoral veins. Death appeared to have resulted from starvation alone.[34]

Gull observed that slow pulse and respiration seemed to be common factors in all the cases he had observed. He also observed that this resulted in below-normal body temperature and proposed the application of external heat as a possible treatment. This proposal is still debated by scientists today.[35]

Gull also recommended that food should be administered at intervals varying inversely with the periods of exhaustion and emaciation. He believed that the inclination of the patient should in no way be consulted; and that the tendency of the medical attendant to indulge the patient ("Let her do as she likes. Don't force food."), particularly in the early stages of the condition, was dangerous and should be discouraged. Gull states that he formed this opinion after experience of dealing with cases of anoerexia nervosa, having previously himself been inclined to indulge patients' wishes.[29]

Gull–Sutton Syndrome (chronic Bright's disease)

In 1872, Sir William Gull and Henry G. Sutton, M.B., F.R.C.P. presented a paper[36] that challenged the earlier understanding of the causes of chronic Bright's Disease.

The symptoms of Bright's Disease had been described in 1827 by the English physician Richard Bright who, like Gull, was based at Guy's Hospital. Dr. Bright's work characterised the symptoms as caused by a disease centred on the kidney. Chronic Bright's disease was a more severe variant, where other organs are also affected.

In their introduction, Gull and Sutton point out that Dr. Bright and others "have fully recognised that the granular contracted kidney is usually associated with morbid changes in other organs of the body" and that these co-existent changes were commonly grouped together and termed "chronic Bright's disease." The prevailing opinion at the time was that the kidney was the organ primarily affected, inducing a condition that would spread to other parts of the body and thereby cause other organs to suffer.

Gull and Sutton argued that this assumption was incorrect. They presented evidence to show that the diseased state could also originate in other organs, and that the deterioration of the kidney is part of the general morbid change, rather than the primary cause. In some cases examined by Gull and Sutton, the kidney was only marginally affected while the condition was far more advanced in other organs.

Gull and Sutton's main conclusion was that the morbid change in the arteries and capillaries was the primary and essential condition of the morbid state known as chronic Bright's disease with contracted kidney. They stated that the clinical history may vary according to the organs primarily and chiefly affected; the condition could not be expected to follow a simple and predictable pattern.

Myxoedema

In 1873, Sir William Gull delivered a paper[37] alongside his Anorexia nervosa work in which he demonstrated that the cause of myxoedema is atrophy of the thyroid gland. This paper, titled "On a cretinoid state supervening in adult life in women" was to be the better known of the two for many years.

The background to Gull's work was research performed by Claude Bernard in 1855 around the concept of the Milieu intérieur and subsequently by Moritz Schiff in Bern in 1859, and who showed that thyroidectomy in dogs invariably proved fatal; Schiff later showed that grafts or injections of thyroid reversed the symptoms in both thyroidectomised animals and humans. He thought the thyroid liberated some important substance into the blood. Three years earlier, Charles Hilton Fagge, also of Guy's Hospital, had produced a paper on 'sporadic cretinism'.

Gull's paper related the symptoms and changed appearance of a Miss B:

After the cessation of the catamenial period, became insensibly more and more languid, with general increase of bulk ... Her face altering from oval to round ... the tongue broad and thick, voice guttural, and the pronunciation as if the tongue were too large for the mouth (cretinoid) ... In the cretinoid condition in adults which I have seen, the thyroid was not enlarged ... There had been a distinct change in the mental state. The mind, which had previously been active and inquisitive, assumed a gentle, placid indifference, corresponding to the muscular languor, but the intellect was unimpaired ... The change in the skin is remarkable. The texture being peculiarly smooth and fine, and the complexion fair, at a first hasty glance there might be supposed to be a general slight oedema of it ... The beautiful delicate rose-purple tint on the cheek is entirely different from what one sees in the bloated face of renal anasarca.

A few years later, in 1888, this condition would be named myxoedema[38] by W. M. Ord.

Spinal Cord and Paraplegia

Paraplegia is a condition usually resulting from injury to the spinal cord. This was a long-term interest of Gull's dating back at least to his three Goulstonian lectures of 1848, titled On the nervous system, Paraplegia and Cervical paraplegia – hemiplegia.[39]

Gull divided paraplegia into three groups: spinal, peripheral, and encephalic, where the spinal group related to paralyses caused by damage to the spinal cord; the peripheral group comprised disorders that occur when multiple parts of the nervous system fail simultaneously; and the encephalic group comprised partial paralyses caused by a failure of the central nervous system, possibly related to failure of the blood supply or a syphilitic condition.

Gull's main work on paraplegia was published between 1856 and 1858. Along with the French neurologist Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard, his work enabled paraplegic symptoms to be understood in context with the prevailing, limited understanding of spinal cord pathology, for the first time. He presented a series of 32 cases, including autopsies in 29 instances, to correlate the clinical and pathological features.[40]

He acknowledged, however, that nothing was more difficult than "the determination at the bedside, of the causes". Pathologically softening and inflammation were sometimes evident, but in many instances no obvious aetiology was found. One might have to seek for 'atomical' as distinguished from 'anatomical' causes, he speculated. He described two types of partial lesions, one confined to a segment of the spinal cord, the other extending longitudinally in one of its columns. He noticed and was puzzled by degenerations of the posterior columns that could cause an 'inability to regulate motor power'.

Gull recognised girdle pain as seldom absent from extrinsic compression, often signifying meningeal involvement. Paralysis of the lower extremities could, he thought, be consequent upon diseases of the bladder and kidneys ('urinary paraplegia'). The bladder infection was the source of inflammatory phlebitis extending from pelvic to spinal veins.

Meningitis with myelitis was found and attributed to exposure to cold or fatigue.

In five traumatic cases, the vertebral column was often but not invariably fractured and could compress the cord. He recorded one instance in a 33-year-old woman of a thoracic disk prolapse compressing the cord, without evident trauma. Tumours also figured in seven of his 32 patients; two were metastatic from kidney and lung. Two had intramedullary cervical tumours, and one, a Guy's Hospital nurse, probably had a cystic astrocytoma.[41]

Earlier work by the Irish physician Robert Bentley Todd (1847), Ernest Horn, and Moritz Heinrich Romberg(1851) had described Tabes dorsalis and noted atrophy of the spinal cord, but in an important paper, Gull also stressed the involvement of the posterior column in paraplegia with sensory ataxia [12].[41]

Quotes

"Fools and savages explain; wise men investigate." William Withey Gull – A Biographical Sketch (T. D. Acland), Memoir II.

"That the course of nature may be varied we have assumed by our meeting here today. The whole object of the science of medicine is based on this assumption" British Medical Journal, 1874, 2: 425.

"I do not know what a brain is, and I do not know what sleep is, but I do know that a well-fed brain sleeps well" Quoted in St. Bartholomew's Hospital Reports, 1916, 52: 45.

"The foundation of the study of Medicine, as of all scientific inquiry, lies in the belief that every natural phenomenon, trifling as it may seem, has a fixed and invariable meaning" Published Writings, "Study of Medicine"

"If facts be nature's words, our words should be true sign of nature's facts. A word rightly imposed is a landmark indicating so much recovered from the region of ignorance" Published Writings, Volume 156, "Study of Medicine"

"Never forget that it is not a pneumonia, but a pneumonic man who is your patient. Not a typhoid fever, but a typhoid man" Published Writings (edited by T. D. Acland), Memoir II.

"Realize, if you can, what a paralyzing influence on all scientific inquiry the ancient belief must have had which attributed the operations of nature to the caprice not of one divinity, but of many. There still remains vestiges of this in most of our minds, and the more distinct in proportion to our weakness and ignorance." British Medical Journal, 1874, 2: 425.

Links to the 1888 Whitechapel murders

Sir William Gull features in theories and fictional works in connection with the Whitechapel "Jack the Ripper" murders of 1888. These are usually (though not always) associated with variants of conspiracy theories involving the Royal Family and the Freemasons.

1895–1897 – U.S. newspaper reports

The earliest known allegation that links the Whitechapel murders with a prominent London physician (not necessarily Gull) was in two articles published by a number of US newspapers between 1895 and 1897.

The first article appeared in the Fort Wayne Weekly Sentinel (24 April 1895),[42] the Fort Wayne Weekly Gazette (25 April 1895)[43] and the Ogden Standard, Utah.[44] It reported an alleged conversation between William Greer Harrison, a prominent San Francisco citizen, and a Dr Howard of London. According to Howard, the murderer was a "medical man of high standing" whose wife had become alarmed by his erratic behaviour during the period of the Whitechapel murders. She conveyed her suspicions to some of her husband's medical colleagues who, after interviewing him and searching the house, "found ample proofs of murder" and committed him to an asylum.

Variations of the second article appeared in the Williamsport Sunday Grit (12 May 1895);[45] the Hayward Review, California (17 May 1895);[46] and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (28 December 1897).[47] This article comments: "the identity of that incarnate fiend was settled some time ago" and that the murderer was "a demented physician afflicted with wildly uncontrollable erotic mania." It repeats some of the details in the earlier report, adding that Dr Howard "was one of a dozen London physicians who sat as a commission in lunacy upon their brother physician, for at last it was definitely proved that the dread Jack the Ripper was a physician in high standing and enjoying the patronage of the best society in the West End of London." The article goes on to allege that the preacher and spiritualist Robert James Lees played a leading role in the physician's arrest by using his clairvoyant powers to divine that the Whitechapel murderer lived in a house in Mayfair. He persuaded police to enter the house, the home of a distinguished physician, who was allegedly removed to a private insane asylum in Islington under the name of Thomas Mason. Meanwhile the disappearance of the physician was explained by announcing his death and faking a funeral – "an empty coffin, which now reposes in the family vaults in Kensal Green, is supposed to contain the mortal remains of a great West End physician, whose untimely death all London mourned." (This detail does not correspond with Sir William Gull, who was buried in the churchyard at Thorpe-le-Soken in Essex.)

The identity of the Dr Howard who is alleged to have provided the information for the first article was never established. On 2 May 1895, the Fort Wayne Weekly Gazette published a follow-up quoting William Greer [sic] as reaffirming the accuracy of the story, and describing Dr. Howard as a "well-known London physician who passed through San Francisco on a tour of the world several months ago".[48] A further follow-up article in the London People on 19 May 1895, written by Joseph Hatton, identified him as Dr. Benjamin Howard, an American doctor who had practised in London during the late 1880s. The article was shown to Dr. Benjamin Howard on a return visit to London in January 1896, prompting a strong letter of denial published in The People on 26 January 1896:

In this publication my name is dishonourably associated with Jack the Ripper – and in such a way – as if true – renders me liable to shew cause to the British Medical Council why my name with three degrees attached should not be expunged from the Official Register. Unfortunately for the Parties of the other part – there is not a single item of this startling statement concerning me which has the slightest foundation in fact. Beyond what I may have read in the newspapers, I have never known anything about Jack the Ripper. I have never made any public statement about Jack the Ripper – and at the time of the alleged public statement by me I was thousands of miles distant from San Francisco where it was alleged that I made it.[49]

1970 – Criminologist article (Thomas Stowell)

Dr. Thomas Eldon Alexander Stowell, C.B.E., M.D., F.R.C.S. published an article in The Criminologist entitled "'Jack the Ripper' – A Solution?"[50]

Stowell was a junior colleague to Dr Theodore Dyke Acland, Gull's son-in-law. He alleges that one of Gull's patients was the Whitechapel murderer. He refers to the killer as "S" throughout the article without ever identifying him, but the identity of "S" is widely presumed to be Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, Queen Victoria's grandson and heir presumptive to the throne. Stowell writes,

"S" was the heir to power and wealth. His grandmother, who outlived him, was very much the stern Victorian matriarch... His father, to whose title he was the heir, was a gay cosmopolitan and did much to improve the status of England internationally. [At 21, he was] gazetted to a commission in the army... He resigned his commission shortly after the raiding of some premises in Cleveland Street, which were frequented by aristocrats and well-to-do homosexuals."

Stowell apparently devised his theory using Sir William Gull's private papers as his primary source material. However, this cannot be confirmed as Stowell died a few days after publishing his article and his family burned his papers. Gull (who was named in the article) supposedly left papers showing that "S" had not died of pneumonia, as had been reported, but of tertiary syphilis. Stowell states that "S" caught syphilis in the West Indies while touring the world in his late teens and it was this illness that brought on a state of insanity which led to the murders.

He goes on to allege that "S" was certified insane by Gull and placed in a private mental home, from which he escaped and committed the last, and most brutal, murder of Mary Jane Kelly in November 1888. He then recovered sufficiently to take a five-month cruise before his relapse and death "in his father's country house" of "bronchopneumonia".

1973 – "Jack the Ripper" (BBC mini-series)

In 1973, the BBC broadcast Jack the Ripper, a six-part mini-series in the docudrama format. The series, scripted by Elwyn Jones and John Lloyd, used fictional detectives Detective Chief Inspector Charles Barlow and Detective Inspector John Watt from the police drama Softly, Softly to portray an investigation into the Whitechapel murders.

The series did not reach a single conclusion, but is significant for its inclusion of the first public airing of a story propounded by Joseph "Hobo" Sickert, alleged illegitimate son of artist Walter Sickert. This theory alleges that the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, conspired with Queen Victoria and senior Freemasons, including senior police officers, to murder a number of women with knowledge of an illegitimate Catholic heir to the throne sired by Prince Albert Victor. According to this theory, the murders were carried out by Sir William Gull with the assistance of a coachman, John Netley. Sickert himself later retracted the story, in an interview with the Sunday Times on 18 June 1978. He is quoted as saying, "It was a hoax; I made it all up" and, it was "a whopping fib."[51][52]

1976 – "Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution" (Stephen Knight)

Stephen Knight was a reporter for the East London Advertiser who interviewed Joseph Sickert following the BBC series. He was sufficiently convinced by the story to write a book – Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution – which proposes the Sickert story as its central conclusion. The book provides the inspiration for a number of fictional works related to the Whitechapel murderers.

Knight undertook his own research, which established that there really was a coachman named John Netley; that an unnamed child was knocked down in the Strand in October 1888 and that a man named "Nickley" attempted suicide by drowning from Westminster Bridge in 1892. He was also provided with access to Home Office files, from which a number of contemporary police reports were made public for the first time.

Knight's claim that Sir William Gull, along with various others, was a high-ranking Freemason, is disputed. Knight writes:

It is impossible to find out if some of the lesser known people in Sickert's story were Masons. The chief characters certainly were. Warren, Gull, and Salisbury were all well advanced on the Masonic ladder. Salisbury, whose father had been Vice Grand Master of All England, was so advanced that in 1873 a new Lodge was consecrated in his name. The Salisbury Lodge met at the premier Masonic venue in England, the Freemasons' Hall in Great Queen Street, London.

This claim is refuted by John Hamill, former Librarian for the Freemasons' United Grand Lodge of England (subsequently the Director of Communications). Hamill writes:

The Stephen Knight thesis is based upon the claim that the main protagonists, the Prime Minister Lord Salisbury, Sir Charles Warren, Sir James Anderson and Sir William Gull were all high-ranking Freemasons. Knight knew his claim to be false for, in 1973, I received a phone call from him in the Library, in which he asked for confirmation of their membership. After a lengthy search I informed him that only Sir Charles Warren had been a Freemason. Regrettably, he chose to ignore this answer as it ruined his story.[53]

Popular culture since 1976

In 1979, the fictional character Sir Thomas Spivey, portrayed by actor Roy Lansford, appears in Murder by Decree, starring Christopher Plummer as Sherlock Holmes and James Mason as Doctor Watson. Sir Thomas Spivey, a Royal physician whose character is based on Sir William Gull, is revealed as the murderer in a plotline based on Stephen Knight's Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution.[54] Spivey is depicted as assisted by a character named William Slade, himself based on John Netley.

A fictionalised Sir William Gull appears in Iain Sinclair's 1987 novel White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings in a plotline based on Stephen Knight's Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution.

Sir William Gull is portrayed by Ray McAnally in 1988[55] in a TV dramatisation of the murders, starring Michael Caine and Jane Seymour. The plotline reveals Sir William Gull as the murderer, assisted by coachman John Netley, but otherwise excludes the main elements of the Royal conspiracy theory.

From 1991 to 1996, a fictionalised Sir William Gull is featured in the graphic novel From Hell by writer Alan Moore and artist Eddie Campbell. The plotline depicts Sir William Gull as the murderer and takes Stephen Knight's Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution as its premise. Eddie Campbell records in his blog,[56] that

I've always liked to imagine that our William Gull is a fiction who just happens to share a name with a real one who existed once.

The story "Royal Blood" told in John Constantine, Hellblazer (1992, DC Comics) mentions Jack the Ripper being Sir William Gull possessed by a demon called Calibraxis.[57]

The fictional character "Sir Nigel Gull" appears in the 1993 novel The List of Seven by Mark Frost. "Sir Nigel Gull" is depicted as a Royal physician and appears to be based on Sir William Gull. The plotline has an occult theme that features Prince Edward, Duke of Clarence but does not reference the Whitechapel murders.

The 1997 TV series Timecop reveals Gull as the Ripper in its pilot, "A Rip in Time".

In a 2001 film adaptation of the graphic novel From Hell, Sir William Gull is portrayed by Sir Ian Holm.

Actor Peter Penry-Jones portrays Sir William Gull in 2004's Julian Fellowes Investigates: A Most Mysterious Murder – The Case of Charles Bravo – a dramatised documentary investigating the unsolved murder of barrister Charles Bravo in 1876.

Gull appears as a character in Brian Catling's 2012 novel, The Vorrh, where accounts of his relationship with Eadweard Muybridge and work on anorexia are blended into the fantasy narrative.

References

- The Times, 30 January 1890

- Paul Begg, Jack the Ripper – The Facts pp. 395–396 ISBN 1-86105-687-7

- Stewart P Evans & Donald Rumbelow, Jack the Ripper – Scotland Yard Investigates p. 261 ISBN 0-7509-4228-2

- Martin Fido, The Crimes, Detection & Death of Jack the Ripper pp. 185–196 ISBN 0-297-79136-2

- Kevin O'Donnell (1997). The Jack the Ripper Whitechapel Murders. Ten Bells. p. 170. ISBN 0-9531269-1-9.

- "Jack the Ripper – The Life and Possible Deaths of Sir William Gull". Casebook. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- Sir William Hale-White (1935). Great Doctors of the 19th Century. pp. 208–226.

- "Transactions of the Clinical Society of London Volume 18 1886". Clinical Society. 1885. Retrieved 23 October 2012. archive.org

- Great Doctors of the 19th Century (1935); ISBN 0-8369-1575-5, Sir William Hale-White, p. 217

- The Times on 18 December 1871

- "No. 23821". The London Gazette. 23 January 1872. p. 231.

- The New York Times, 2 March 1890.

- Jex-Blake, Sophia (1886). Medical Women: A Thesis and a History. Oliphant, Anderson, & Ferrier. pp. 222–224.

- Hussey, Kristin (5 October 2018). "Life and death on the ward: the case of Helen Prideaux". RCP Museum. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- British Medical Journal, 27 February 1886

- British Medical Journal, 16 January 1886

- British Medical Journal, 7 September 1895

- British Medical Journal, 27 August 1898

- "Corresponding members in the United Kingdom" (PDF). Trans Med Chir Soc Edinb. 3: viii. 1884. PMC 5499423.

- The Times, 30 January 1890

- The New York Times, 2 March 1890

- The Brisbane Courier, 12 March 1890, page 3

- Mark Twain's Notebook, Albert Paine ISBN 978-1-4067-3689-2

- The New York Times, 2 March 1890 (reprinted from the London World)

- Finlayson, J. (1890). "Account of a Ms. Volume, by William Clift, Relating to John Hunter's Household and Estate; and to Sir Everard Home's Publications". BMJ. 1 (1526): 738–44. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.1526.738. PMC 2207643. PMID 20752999.

- The Times, London, 21 March 1890

- Kevin O'Donnell The Jack the Ripper Whitechapel Murders (1997) ISBN 0-9531269-1-9, p. 179

- Gull WW: Address in medicine delivered before the Annual Meeting of the British Medical Association at Oxford" Lancet 1868;ii:171–176

- Medical Papers, p. 310

- Anorexia Nervosa (Apepsia Hysterica, Anorexia Hysterica) (1873) William Withey Gull, published in the 'Clinical Society's Transactions, vol vii, 1874, p. 22

- Medical Papers, pp. 311–314

- Medical Papers, pp. 305–307

- Medical Papers, pp. 307–309

- Medical Papers, 309

- Emilio Gutierrez; Reyes Vazquez; Peter J. V. Beumont (2002). "Do people with anorexia nervosa use sauna baths? A reconsideration of heat-treatment in anorexia nervosa" (PDF). Eating Behaviors. 3 (2): 133–142. doi:10.1016/S1471-0153(01)00051-4. PMID 15001010.

- "On the Pathology of the Morbid State commonly called Chronic Bright's Disease with Contracted Kidney ("Arterio-Capillary Fibrosis")" (1872), Sir William Withey Gull, Bart, M.D., D.C.L., F.R.S., and Henry G. Sutton, M.B., F.R.C.P., Medico-Chirurgical Transaction, vol lv 1872, p. 273.

- Gull WW: On a cretinoid state supervening in adult life in women. Trans Clin Soc Lond 1873/1874; 7:180–185.

- Ord WM: Report of a committee of the Clinical Society of London nominated 14 December 1883, to investigate the subject of myxoedema. Trans Clin Soc Lond 1888; 21(suppl).

- Medical Papers, pp. 109–162

- Medical Papers, pp. 163–243

- J.M.S. Pearce (2006). "Sir William Withey Gull (1816–1890)". European Neurology. 55 (1): 53–56. doi:10.1159/000091430. PMID 16479123.

- "Jack the Ripper – Fort Wayne Weekly Sentinel – 24 April 1895". Casebook. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Jack the Ripper – Fort Wayne Gazette – 25 April 1895". Casebook. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Jack the Ripper – Ogden Standard – 24 April 1895". Casebook. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Jack the Ripper – Williamsport Sunday Grit – 12 May 1895". Casebook. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Jack the Ripper – Hayward Review – 17 May 1895". Casebook. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Jack the Ripper – Brooklyn Daily Eagle – 28 December 1897". Casebook. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ""Jack the Ripper", Fort Wayne Gazette, 2 May 1895". Casebook. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- The Crimes, Detection and Death of Jack the Ripper (1987), ISBN 0-297-79136-2, Martin Fido, pp. 190–191

- Stowell, Thomas (November 1970). "'Jack the Ripper' – A Solution?". The Criminologist. 5 (18).

- The Sunday Times, 18 June 1978

- Jack the Ripper: The Complete Casebook, Donald Rumbelow, pp. 212, 213

- MQ MAGAZINE Issue 2 – Jack the Ripper: Exploring the Masonic link. Mqmagazine.co.uk. Retrieved on 2012-04-20.

- "Freemasonry and the Ripper". Casebook.org. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- Jack the Ripper (1988). IMDb.com

- "The Fate of the Artist: July 2009". Eddiecampbell.blogspot.com. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- Hellblazer: Bloodlines | Vertigo. Dccomics.com (2007-11-14). Retrieved on 2012-04-20.

Bibliography

- Medical Papers, Sir William Withey Gull, edited by T D Acland (1894).

External links

- William Withey Gull – A Biographical Sketch (1896)

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 1885–1900.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 714.